“We continue to count on the valuable contributions of the Arms Control Association.”

Membership bids by the two southern Asian countries present a unique challenge for the world’s leading multilateral nuclear export control group.

November 2024

By Mark Hibbs

The Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), the world’s leading multilateral nuclear export control arrangement, will be 50 years old in 2025. In advance of this occasion, some observers and officials among the participating governments have suggested that the group prioritize discussions about expanding the NSG membership, prompted by applications from India and Pakistan that have been awaiting decisions for several years. It is possible that such an exercise already is underway in internal and informal policy circles; official NSG public statements about recent annual plenary meetings note tersely that consideration of pending applications and India’s relationship to the NSG in particular is ongoing.1

The lack of action is long-standing. Although India and Pakistan filed separate, formal applications for NSG membership in 2016, the group never reached consensus on either candidate country. This followed 15 years during which the NSG wrestled with the topic of expanding membership, with the Indian prospect proving especially contentious. The global political environment today is different than it was a decade ago, generating speculation that, with China’s cooperation, a renewed membership effort by India and Pakistan could succeed.

Nevertheless, barring unforeseen developments, it is unlikely that the NSG participating governments will actively promote including India or Pakistan anytime soon. That will not happen until the members are confident that both countries will embrace and help sustain the group’s export control and nonproliferation mission. Influential NSG members suggest that India and Pakistan must work harder to reach this standard. Moreover, a decision to admit either or both states must be predicated on an understanding within the group about what the requirements should be for admitting new members.

The NSG sets the nonproliferation ground rules for the world’s nuclear trade, and the more universal adherence to its guidelines is, the greater the effectiveness. In principle, the nonproliferation regime would benefit from including India and Pakistan in the NSG because both states possess significant nuclear assets. Conversely, if their conduct was not consistent with NSG guidelines and principles, the regime could suffer damage.

Considerations about NSG relations with India and Pakistan are playing out at a moment when the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) is under growing stress from challenges by Iran, North Korea, established nuclear-weapon powers, and rising nuclear technology expectations in non-nuclear-weapon states. The nearly universal treaty is the cornerstone of the multilateral regime to control the spread of nuclear arms, but India and Pakistan are not parties.

The responsibility of NSG participating governments to make a sound decision about these candidates is significant and the task challenging because powerful members might intervene in these cases based on whether India and Pakistan are allies or adversaries. China and the United States bear particular responsibility for their roles in the decision-making.

NSG Beginnings

The 48 NSG members govern global nuclear trade worth about $15 billion annually by implementing two sets of guidelines for the export of nuclear-related items. The first set refers to items specially designed or prepared for nuclear use, and the second set concerns dual-use items and technologies related to the nuclear fuel cycle and nuclear weaponization.

Governments participating in the NSG, a voluntary mechanism, authorize transfers of listed items for nuclear use according to formal governmental assurances from recipient states. These assurances, for example, exclude the use of transferred items in nuclear explosives and stipulate that the items will be subject to peaceful-use verification. There is a “close interdependence” between the first set of guidelines and the comprehensive safeguards of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). “Almost all refusals by NSG participants of applications for export licenses have concerned states with unsafeguarded nuclear programs.”2

Deciding whether to include India and Pakistan as members is a challenge for the NSG from several perspectives. The historical record of multilateral nuclear trade controls for most of the last half century implies that, for the suppliers to admit India or Pakistan, many must revise their proliferation risk assessment concerning these states, which was formed during decades of effort by India and Pakistan to defy and defeat NSG export controls.

The NSG was created in 1975 by the world’s nuclear technology-holding countries (Canada, France, Japan, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, the United States, and West Germany) in direct response to India having conducted its first nuclear explosive test one year earlier. To achieve this feat, India used items that it obtained from Canada and the United States under bilateral agreements for peaceful nuclear cooperation.

During the same time period, Pakistan was quietly preparing to go forward with secret nuclear activities that would allow it to match India, its main adversary, should that country obtain nuclear arms. Accordingly, from the beginning, the NSG has viewed India and Pakistan as principal targets of the group’s overall effort to restrict and deny trade in nuclear equipment, dual-use items, materials, and technology on the grounds that the two states are proliferation risks.

India’s 1974 test challenged nuclear suppliers by underscoring the essential dual-use nature of nuclear equipment and materials, which can be used for peaceful and nonpeaceful purposes. In this case, India made and detonated an explosive device using plutonium that it separated from uranium fuel it irradiated in a reactor supplied by Canada. Operation of the reactor, specifically moderating the nuclear reaction in the core, relied on heavy water that the United States supplied to India.

India claimed that its explosive nuclear test was not for a nuclear bomb but for a “peaceful nuclear device.” This designation may have been permitted by Canada’s agreement with India for supply of the reactor in 1954, but according to declassified U.S. government documents, such use was expressly disallowed by the U.S. agreement with India for the supply of the heavy water. “Development of [a peaceful nuclear explosion would be] tantamount to development of nuclear weapons,” the U.S. Department of State informed the embassy in India four years prior to the test.3 The United States was satisfied that Pakistan, in response to the Indian test, was preparing to embark on its own nuclear weapons development as part of its nuclear energy program.4

Thereafter and even now, nuclear supplier states in the NSG restricted exports of nuclear items to India and Pakistan, especially highly sensitive items such as those needed for uranium enrichment and fuel reprocessing. India and Pakistan independently continued to develop their nuclear technology and nuclear materials-processing capacities, including through nuclear trade carried out in defiance of NSG guidelines for participating governments and their suppliers. In May 1998, India and Pakistan each conducted a series of nuclear explosive tests and then declared themselves nuclear-armed states.

The NPT Conundrum

The nuclear weapons-testing achievements of India and Pakistan defied the 1995 indefinite extension of the 1970 NPT, which excluded India from a list of five states it identified as lawful possessors of nuclear arms. The tests also alerted nonproliferation-minded powers that Indian and Pakistani nuclear capabilities must be taken seriously.

That message was not lost on the Republican leadership in the United States. Even before President George W. Bush took office in January 2001, his designated cabinet members were preparing to initiate civilian nuclear cooperation with India, which had been blocked by U.S. law enacted in response to India’s 1974 nuclear blast. Bush and Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh went on to include nuclear energy in a bilateral framework agreement toward a “strategic partnership,” in which the United States viewed India’s democratic aspirations and growing economic, technological, and military power as a counterweight to an increasingly formidable China.

On a parallel track, the NSG in 2001 adopted guidelines for participating governments to consider when evaluating the credentials of future NSG membership candidates. That step was not a coincidence; some NSG participants anticipated that an increasingly wealthy, technology-endowed, and more ambitious India, supported by the United States including by advancing India’s nuclear energy capacities, would eventually seek NSG membership.

The 2001 NSG candidate guidance included five specific factors that NSG members should consider.5 One strongly advocated factor is that candidate states be in full compliance with the NPT. In 1997 and following the decision by NPT states-parties to extend the treaty indefinitely, the NSG formally singled out the NPT as a critical signpost for a state’s membership qualification. The guidance did not expressly require that a new NSG member be a party to the NPT. It stated instead that NPT participation was one factor “among others,” implying that a candidate might be admitted based on NSG members’ specific considerations, including political considerations. In the background loomed the fact that when the NSG was established a quarter century earlier, it admitted France, at the time a non-NPT state. The net effect of the “factors” statement was to prompt further internal debate about membership criteria for non-NPT states, including what commitments candidates might offer in lieu of NPT compliance.

During subsequent Indian-U.S. bilateral negotiations on civilian nuclear cooperation, the two countries issued joint statements signaling that they favored adjusting international trade rules to facilitate a resumption of U.S. nuclear trade with India. In 2008, NSG members, under pressure from the United States, granted India an exemption from NSG guidelines to accommodate nuclear trade foreseen under the Indian-U.S. bilateral nuclear cooperation agreement. Thereafter, NSG participants discussed and debated the case for future Indian participation in the group; in 2016, India and Pakistan formally applied for NSG membership.

The two applications were not approved by NSG participants. Rafael Mariano Grossi, an Argentine diplomat and former NSG chairman who now heads the IAEA, worked closely with U.S. counterparts to craft a solution that would permit India to join the NSG based on criteria that could apply to all future candidates, including Pakistan.6 One NSG participating government objected to this gambit on procedural grounds, and others surmised that Grossi’s proposal appeared to favor membership for India but not for Pakistan. Since 2018, the NSG has not made any membership decisions, although in the meantime the Indian and Pakistani applications have been joined by applications filed by Jordan and Namibia.

The NSG’s ambiguous 2001 NPT benchmark remains a sticking point for consideration of Indian and Pakistani membership. For the NSG, associating the arrangement with the NPT was a logical step for several reasons. The treaty’s Article I bans nuclear-armed states from assisting others in acquiring nuclear weapons, Article II prohibits non-nuclear-armed states from attaining that same result, and Article III calls for IAEA verification (“safeguards”) to be implemented in states that are party to the treaty “with a view to preventing diversion of nuclear energy for peaceful uses to nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices.” For NSG participants, conditioning trade on the obligations expressed in these first three NPT articles reduced the risk that their commerce would contribute to proliferation.

Washington’s 2008 request for an NSG exception to permit India to import nuclear wares necessitated that the United States apply direct pressure on some NSG participants. That was in part because in 1992 the United States had prompted the group to amend its guidelines to deny nuclear-specific transfers to all non-nuclear-weapon states, formally including India, that did not have comprehensive IAEA safeguards on all their nuclear materials. The logic for that denial rule seemed clear: Nuclear-armed states that are not NPT parties, including India and Pakistan, are not subject to the treaty’s obligations and restraints, thereby increasing the proliferation hazard faced by suppliers from nuclear trade with these states.

India and Pakistan have not joined the NPT for national security reasons, but nuclear leaders in these states also have objected that the NPT is an expression of discrimination by rich, technology-endowed states against poor states with few nuclear resources. The discrimination, in their view, includes the NPT definition of a nuclear-weapon state as one that manufactured and tested a nuclear explosive device before January 1, 1967. This rule permitted China and France, both NSG members, to join the NPT as nuclear-weapon states in 1992. Unlike China and France, India and Pakistan may not join the NPT and retain their nuclear weapons.

For three decades, India deplored the NSG and unilateral trade bans, particularly by Canada and the United States, in response to its nuclear explosive test. India’s attitude began changing during the 2000s as the country sought to forge strategic links to the United States and increasingly identified with the world’s nuclear haves. In the process, Indian policymakers and pundits crafted rationales to justify New Delhi’s desire for NSG membership and to explain to domestic audiences the switch from opposition to support for an instrument that India long considered an unjust cartel.

Pakistan also spent years relentlessly challenging NSG guidelines. When Pakistan confirmed in 2004 that its leading nuclear procurement agent shared the country’s uranium-enrichment know-how, largely stolen from Europe, with clandestine nuclear programs in Iran, Libya, and North Korea, Pakistan was widely deplored. Thereafter, it shifted its posture to embrace nuclear trade controls. Yet, the benefits of NSG membership likely will be fewer than what advocates in New Delhi or Islamabad have hoped or claimed.

The Value of NSG Membership

India and Pakistan have evolved, even reversed, their public diplomacy on nuclear nonproliferation rulemaking. During the first half century following independence in 1947, both states considered nonproliferation a cover for advanced states to deny technology to others. More recently, the Pakistani proliferation revelations; the emergence of China, India’s rival, as a great power; destabilizing nuclear developments in Iran and North Korea; the rise of international terrorism; and nuclear war-posturing by Russia over Ukraine have raised the profile of nuclear proliferation as a policy concern in both South Asian states.7 For good reasons, India and Pakistan today would welcome inclusion in the NSG’s technically focused, multilateral rulemaking discussions concerning the eligibility requirements for participation in nuclear trade and also the specifications for listing controlled items.

Despite this, NSG membership likely would not significantly boost India’s participation in the supply chain for new nuclear energy projects carried out with foreign partners, and it would not be essential to India meeting its climate mitigation targets. In addition, membership likely would not influence India’s access to foreign supplies of equipment, uranium fuel, or engineering services for its safeguarded nuclear power plants. For India, these interests could be addressed through its 2008 NSG waiver, which permits India to import nuclear items for peaceful use from foreign suppliers regardless of NSG guidelines that would otherwise deny that commerce.8

A decade ago, India made plans to set up 12 new nuclear power plants in cooperation with industry in the United States and France. So far, these projects have not materialized on the ground. In the meantime, the cost of nuclear power investments has increased, and U.S. and French firms face capacity and financial challenges that may lead them to prioritize investments carrying less project risk. According to government officials in NSG member states participating in these projects, India’s failure to agree to nuclear liability terms that comport with world standards, not India’s nonmembership in the NPT, is the most significant obstacle to realizing these projects.

Notwithstanding NSG restrictions on nuclear trade, India and Pakistan for many years have benefited significantly from nuclear commerce with NSG supplier states. Until 1992, when the guidelines were amended to require comprehensive IAEA safeguards in recipient non-nuclear-weapon states as a condition of nuclear trade, the NSG permitted suppliers to transfer reactors and other nuclear items to both South Asian states under transaction-specific IAEA safeguards.

On this basis, Russia and China have exported reactors and other items to India and Pakistan, respectively, in some cases with impunity, ignoring the reservations and objections of many NSG participants. Russia brushed off such concerns in supplying fuel for a nuclear power plant in India after 1992 by claiming that failure to supply the fuel would raise safety risks.9 Despite the reservations and objections of many NSG participants, China has exported and continues to export nuclear power plants to Pakistan, claiming that the supply agreements for all these transfers were concluded before 1992.10

Following up on the precedent-setting 2006 Indian-U.S. nuclear cooperation accord and India’s 2008 NSG trade restrictions waiver, India has concluded numerous bilateral nuclear cooperation agreements, including with at least 10 NSG supplier states.11 These agreements in the long term may enable India to obtain from NSG suppliers a broad range of nuclear items that advance its peaceful-use nuclear energy development. The risk that, without NSG membership, suppliers would revoke India’s 2008 waiver is minimal, given the requirement that a consensus of NSG participants would be necessary to take that step.

The Anticipated Chinese-Indian Reset

As 2024 draws toward a close, observers and media in India are speculating about prospects for a coming “reset” in Chinese-Indian relations following more than a decade of heightened bilateral tension that has led to military clashes on their shared Himalayan frontier. With a view toward this anticipated warming diplomacy, “India desperately needs to revive its [NSG] membership efforts,” according to one observer, apparently because India has made no headway since its failed effort in 2016.12

Around that same time, China encouraged Pakistan to file an application for membership in step with India, according to participants. China also made clear that it would not approve India’s membership application without, in effect, opening the way for Pakistan’s membership on the grounds that admitting one non-NPT state alone would discriminate against others unless universal criteria were applied.

Some Indian commentators have expressed hope that China and India can agree to a compromise on this matter. Although the government of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi publicly reaffirmed its resolve to seek NSG membership, this goal is dwarfed by the complex, pressing national security issues that divide Beijing and New Delhi.

Some Indian commentators have expressed hope that China and India can agree to a compromise on this matter. Although the government of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi publicly reaffirmed its resolve to seek NSG membership, this goal is dwarfed by the complex, pressing national security issues that divide Beijing and New Delhi.

In the last eight years, India and Pakistan have embraced very different blueprints for enabling the NSG to expand to include non-NPT states. India has insisted on being admitted based on a state-specific approach considering only India’s qualifications. Pakistan, in line with China’s views, has argued that non-NPT states should be admitted

based on nondiscriminatory criteria that would be applied to all applicants without exception.

As in 2016, some officials and observers argue that admitting only one of them would ensure that that state thereafter would veto membership by its adversary. In theory, NSG participants could agree that if one of the two states were admitted, the new member may not vote against the second state’s application. That procedure, however, would compromise the NSG’s consensus rule for decision-making and, in this case, would affect a decision of watershed importance.

The Geopoliticized Environment

In the past, NSG participants have made important decisions on membership applications by “considering evidence of whether a state will behave in the interest of the nuclear export control regime.”13 This approach also governs the group’s evaluation of membership for India and Pakistan. According to participants, a number of significant supplier states in Europe, North America, and the Asia-Pacific region do not support admitting India or Pakistan now, even though some of these governments have expressed official support in principle for India’s participation.

Between 2016 and 2018, India, supported by the United States, joined three multilateral export control regimes: the Wassenaar Arrangement for munitions and dual-use items, the Missile Technology Control Regime for missiles and related technology, and the Australia Group for chemical and biological weapons-related goods. India viewed its membership in these arrangements as providing credibility for its pending NSG application. These three regimes do not require states’ compliance with the NPT for admission, but India’s performance record in these arrangements has raised concerns at the working level among NSG participating governments about India’s like-mindedness. Inside these regimes, “India has been difficult,” according to one NSG government official, without providing details that are subject to confidentiality rules in all four export control arrangements.

Pakistan’s behavior and status likewise raise questions about whether it is in harmony with the NSG mission. Pakistan is not a member of any of the above-mentioned export control regimes, and it does not have a significant track record in administering nuclear trade controls. There is also the matter of Pakistan’s ongoing nuclear-specific and nuclear dual-use trade with Chinese suppliers.14 In the view of some NSG supplier states, Pakistan is not ready for membership at this time.

For NSG participants, it is axiomatic that like-mindedness concerning the group’s export control and nonproliferation mission is essential for the arrangement to function effectively and credibly. The rise of geopolitical pressures and considerations among weighty participants during the last decade, however, is a challenge to like-mindedness. How can participants assure that their verdicts about like-mindedness are about the group’s mission and not about favoring allies or excluding competitors and adversaries?

Washington’s political advocacy of New Delhi’s membership, India’s balancing act in managing its relations with the West and Russia, and China’s sponsorship of its ally Pakistan all pose challenges to NSG participating governments that should focus decision-making on membership applications as strictly as possible on candidates’ nuclear supply, export control, and nonproliferation credentials.15 The ambiguous language of the 2001 membership guidance document, if not carefully applied, might encourage arbitrariness because it was designed to afford participants flexibility in deciding the basis on which a candidate for membership should be admitted.

The NSG has the biggest membership of all four export control arrangements, and participants have discussed whether further expansion, especially to candidates whose like-mindedness may be considered uncertain, would compromise effectiveness. The NSG mission is nuclear export controls and nonproliferation. In contrast, India’s quest for membership has been driven in part by great-power aspirations and domestic electoral politics. If Modi, who began his third term in June, succeeds in attaining NSG membership for India, his ruling BJP party will eclipse its rival, the Indian National Congress Party, which between 2004 and 2009 under the Singh government achieved India’s nuclear breakthrough with the United States and the NSG waiver.

Beginning in 2022, according to Indian media, New Delhi raised its NSG interest with Beijing and had its foreign minister publicly reaffirm India’s expectations about joining the group. Yet, participants report that the NSG currently feels no pressure from either China, including on behalf of Pakistan, or India to force the pace of decision-making on these two applications.16

As it stands now, a significant number of participants do not favor admitting India or Pakistan. In 2016 by some accounts, China alone prevented India’s membership bid from succeeding. Today, as then, China sits at the fulcrum of any resolution of this issue. Without a Chinese-Indian understanding, neither India nor Pakistan will be admitted.

As importantly, before they will be able to join, India and Pakistan will have to convince all NSG members that they share the group’s mission. That is an undertaking challenged by increasing geopolitical tensions and the legacy of powerful nuclear suppliers making exceptions to the NSG principles and guidelines.

ENDNOTES

1. “Public Statement, Plenary Meeting of the Nuclear Suppliers Group,” June 25, 2021, https://www.nuclearsuppliersgroup.org/images/Files%20and%20Documents/Documents

/Public%20Statements/2021_Public-statement_Brussels.pdf.

2. International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), “Communication Received From the Permanent Mission of the Argentine Republic to the International Atomic Energy Agency on Behalf of the Participating Governments of the Nuclear Suppliers Group,” INFCIRC/539/Rev. 8, July 28, 2022 (hereinafter IAEA INFCIRC/539/Rev. 8).

3. “State Department Telegram 160591 to U.S. Embassy India, 29 September 1970, Confidential,” National Security Archive, September 29, 1970, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/document/29492-document-7-state-department-telegram-160591-us-embassy-india-29-september-1970.

4. “Pakistan and the Non-Proliferation Issue,’’ n.d., https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB6/docs/doc20.pdf.

5. “Procedural Arrangement for the NSG,” NSG Aspen Plenary, May, 2001.

6. Ian Stewart and Adil Sultan, “India, Pakistan, and the NSG,” Kings College London, June 10, 2019, https://www.kcl.ac.uk/news/india-pakistan-and-the-nsg.

7. Mark Hibbs, “Eyes on the Prize: India’s Pursuit of Membership in the Nuclear Suppliers Group,” The Nonproliferation Review, Vol. 24, Nos. 3-4 (2017): 280-283.

9. “TVEL to Supply Fuel Pellets for Tarapur NPP (India),” Rosatom, n.d., https://www.rusatom-energy.ru/en/media/rosatom-news/tvel-to-supply-fuel-pellets-for-tarapur-npp-india/ (accessed October 20, 2024).

10. Mark Hibbs, “The Future of the Nuclear Suppliers Group,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP), 2011, pp. 13-18, https://carnegie-production-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/static/files/future_nsg.pdf.

11. Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, “Foreign Countries Having Nuclear Pact With India,” August 11, 2016, https://www.mea.gov.in/rajya-sabha.htm?dtl/27300/QUESTION_NO2812_FOREIGN_COUNTRIES_HAVING_NUCLEAR_PACT_WITH_INDIA.

12. Moksh Suri, “Can India Revive Its Quest for Nuclear Suppliers Group Membership?” The Diplomat, April 1, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/04/can-india-revive-its-quest-for-nuclear-suppliers-group-membership/.

13. Mark Hibbs, “Toward a Nuclear Suppliers Group Policy for States Not Party to the NPT,” CEIP, February 12, 2016, https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2016/02/toward-a-nuclear-suppliers-group-policy-for-states-not-party-to-the-npt?lang=en.

14. Dinakar Peri, “Chinese Dual-Use Cargo Heading to Pakistan Seized,” The Hindu, March 3, 2024, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/ship-suspected-to-contain-dual-use-consignment-for-pakistans-nuclear-programme-stopped-at-nhava-sheva-port-in-mumbai/article67906937.ece.

15. Increasing geopolitical competition among great-power participants in export control regimes in which India is a member may inhibit transparency and availability of reliable information concerning India’s behavior in these mechanisms. Shortly after joining the Missile Technology Control Regime, India partnered with Russia for joint production of an advanced, long-range cruise missile, a development that was criticized by Western participants who had supported India’s membership. See Nuclear Threat Initiative, “India Missile Overview,” November 4, 2019, https://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/india-missile/. India chaired the 2023 plenary meeting of the Wassenaar Arrangement at a time when, given the backdrop of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the United States and other Western participants charged that Russia was obstructing modifications in the Wassenaar control lists. See Emily Benson and Margot Putnam, “Export Controls and Intangible Goods,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, April 11, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/export-controls-and-intangible-goods.

16. According to U.S. administration officials, during the course of the administration of President Donald Trump from 2017 to 2021, India’s interest in obtaining near-term NSG admission receded. During President Joe Biden’s administration, India has not strongly urged the United States to reprioritize India’s candidacy.

Mark Hibbs is a senior nonresident fellow in the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Strategically, India has not been able to achieve what it desired, despite building a nuclear arsenal.

November 2024

By Nasir Hafeez

Fifty years ago, on May 18, 1974, India for the first time detonated a nuclear device at the Pokhran testing site, code-named “Smiling Buddha.” Its leaders claimed they needed this explosive capability for peaceful purposes, such as earth-moving operations, mining, and canal digging.1 Ironically, since then not a single attempt has been made to use a nuclear device to this effect. On the contrary, in 1997, Raja Ramanna, the head of the team that conducted the test, confessed and confirmed in an interview the widespread suspicions that the 1974 Indian nuclear blast was indeed a weapons test.2

Twenty-four years later, also in May and at the same testing site, India conducted five nuclear weapons tests and declared itself a nuclear weapons state. Today, after another 26 years, India is rapidly modernizing its nuclear arsenal and operationalizing its nuclear triad3 under the cover of minimum deterrence and a no-first-use policy. Such a complicated past warrants a retrospective analysis to understand the evolution of the Indian nuclear program and to contextualize the international nuclear cooperation that at its various stages has enabled the development of the necessary infrastructure in this regard. India, despite being critical of the nonproliferation regime, long sought international nuclear cooperation on its own terms and developed the necessary infrastructure for its nuclear weapons program under the guise of peaceful uses. The same process continues even today, albeit in a different manner.

India in the Developing World

India maintains one of the oldest and largest nuclear programs in the developing world.4 Its unique worldview and colonial past play determining roles in adjusting its position on the bargain that led to the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) and other nuclear arrangements.5 Over many years, India has criticized most nonproliferation initiatives, suspecting neocolonial designs. It opposed the U.S. Baruch plan, presented to the UN Atomic Energy Commission in 1946 as the first nuclear disarmament proposal, on the basis that it was meant to prolong the U.S. monopoly over nuclear weapons.6 India has been pursuing strategic autonomy in its foreign policy decision-making, taking a principled stand with its reluctance to be part of any alliance yet benefiting substantially by seeking cooperation from both superpowers during the Cold War under the cover of nonalignment. It is a manifestation of Chanakya Kautilya’s double policy.

India actively participated in all multilateral negotiations on nuclear nonproliferation and disarmament, but refused to enter into any substantial nuclear restraint agreement. In 1965-1968, it was part of the Eighteen Nations Disarmament Committee mandated by a UN resolution to deliberate on the text of the NPT. Although India participated in the negotiations, in the end it refused to sign the final draft and instead proceeded to conduct the nuclear test in 1974. India also played an active role in the negotiations on the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) at the Conference on Disarmament in the mid-1990s by remaining engaged at all stages of the formulations of the treaty text. Nevertheless, repeating the history, India not only vetoed the treaty by refusing to sign it, but also voted negatively in the UN General Assembly when the CTBT resolution was adopted in 1996. Once again, India followed up by conducting multiple nuclear tests in 1998.

A meticulous, scholarly look at Indian nuclear history reveals consistency and continuity of policy. New Delhi has kept its nuclear options open for the military application of nuclear technology while pursuing a peaceful civilian program and continued seeking international cooperation to develop a long-term technological autarky with respect to nuclear research and infrastructure development.7 Indian scientists and policymakers have been aware of the deterrence value of nuclear weapons since the inception of the Indian nuclear program in 1948. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Homi Bhabha, the physicist considered the father of India’s nuclear program, played along with the ruse of the peaceful route as a cover for building the nuclear infrastructure that they could use for weapons-related purposes, if compelled. No pious sentiment could stop them.8

In 1956, India signed a nuclear cooperation agreement with Canada to build its first nuclear reactor. Subsequently, the United States also joined this arrangement and agreed to supply heavy water for the reactor.9 In 1959, India purchased the design of a plutonium uranium extraction plant from Virto Corporation, a U.S. firm whose subsidiary started construction of the plant at Trombay, code named “Phoenix.” This plant was commissioned in February 1964,10 months before the Chinese nuclear test in October.11

In 1963, India signed an agreement with General Electric to acquire two more nuclear reactors for the Tarapur Atomic Power Station as part of the U.S. Atoms for Peace program.12 When the United States signed an agreement with India in 1963 to supply the fuel for India’s first nuclear power reactor at Tarapur, India was allowed to comply with less stringent safeguards than required of other countries.13 Whereas the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission initially insisted on India accepting International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards on the Tarapur plant, India demanded that the safeguards apply only to the U.S.-supplied fuel rather than to the whole plant.14 Thus, the agreement adopted a fuel-based approach to safeguards, rather than the plant-based approach that is usually required by the IAEA.

The U.S. Role in Indian Nuclear Weapons

In this sense, the Indian-U.S. agreement indirectly helped India produce the necessary fissile material for its first nuclear weapon. Restricting IAEA safeguards to the U.S.-sourced fuel allowed India to use non-U.S.-supplied fuel, namely Canadian fuel that was not subject to IAEA safeguards, to make a nuclear explosive device from the spent fuel in Tarapur.15 India refused to accept IAEA jurisdiction over the Canadian fuel.

India already may have acquired sufficient nuclear expertise to conduct nuclear tests by 1964 when China first tested nuclear weapons. Badr-ud-din Tayabji, the Indian representative at the IAEA General Conference in September 1965, gave credence to that assumption when he hinted that India was capable of producing nuclear weapons but had refrained from doing so.16 A month later, almost similar views were expressed by Vishnu C. Tridevi, the Indian representative at the First Committee of the UN General Assembly, when he said that technologically India was undoubtedly “a very advanced nuclear capable country” and that the Indian decision to refrain from manufacturing nuclear weapons was a political calculation.17

Indian scientists understood that they “could use international [that is, U.S.] aid under safeguards to augment an unsafeguarded parallel explosives program.”18 Some experts argued that India violated the letter of its 1961 fuel supply agreement with Canada, which included commitments that the spent fuel, in the form of plutonium extracted from the reactor, would be used only for “peaceful purposes.” Yet, because India did not regard a “peaceful” nuclear explosion as constituting a violation of that agreement, Indian diplomats claimed that the 1974 nuclear test did not violate any agreement with Canada or with the United States.19 Despite these assertions, India “climbed into the nuclear clubhouse on the shoulders of Canadian technology and Canadian aid,” Robert Gillette argued.20

The United States did not publicly criticize the “peaceful” purposes of the Indian nuclear program in view of its strategic concerns against the backdrop of the Chinese nuclear threat.21 Although the United States privately disagreed with the Indian interpretation, officially the Nixon administration stated that “the Indian test did not violate any agreement” with the United States,22 just as India claimed. Eventually, the United States applied no direct sanctions against India. Instead U.S. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger silenced any talk of sanctions within the administration and allowed the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission to continue fueling the Tarapur plant even after the Indian test.23

The United States responded to the Indian nuclear test on the domestic front by enacting the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Act of 1978, which tightened the requirements for nuclear cooperation. The law imposed tough conditions on nuclear exports, demanding full-scope safeguards and the termination of the agreement if a state conducts nuclear tests or engages in activities related to nuclear weapons manufacturing.24 Less than a year later, a dispute surfaced when the United States decided not to supply low-enriched uranium (LEU) fuel to the Tarapur plant. India criticized the decision because the agreement had guaranteed the uninterrupted U.S. supply of fuel for a period of 30 years.

The United States understood the complication and arranged for the supply of fuel from France to the Tarapur plant until 1993.25 Thereafter, France also introduced a full-scope safeguard policy and ceased supplying the fuel in early 1993.26 Ultimately in 1995, India had to seek supply of LEU from the China Nuclear Energy Industry Corporation.27 Overall on the international front, the Indian nuclear test of 1974 intensified nonproliferation efforts to fill in all the loopholes in the existing international nuclear cooperation agreements being signed between different countries, especially regarding dual-use items. One major consequence was establishment of the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), which was created to exercise strict control on all technologies and materials necessary to build nuclear weapons.

Since the beginning, Indian nuclear policy has aimed to promote the cause of nuclear disarmament in the public sphere while developing the necessary infrastructure for its own nuclear weapons program. While India was discussing the draft of the CTBT at the international level, it was weighing its options to conduct nuclear tests at the domestic level. Two attempts were made to conduct nuclear tests, one during Prime Minister Narsima Rao’s government in December 1995 and later during the short-lived Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government in May 1996.28 Both attempts failed due to prior detection of preparations by U.S. satellites and to diplomatic pressure applied to encourage India to abandon the testing plans.

Ever since the establishment of India’s nuclear program, successive governments have pursued the strategy of nuclear ambiguity. The situation changed when the BJP won the 1998 election. Within days of the establishment of the new government, India conducted five nuclear weapons tests on May 11 and 13, 1998, and declared India a nuclear weapons state.29 This display of nuclear weapons capability was not achieved in days or months, but was part of a strategic continuum30 of earlier nuclear policies adopted by previous governments since the inception of the Indian nuclear program.

The international community, especially the United States, criticized the Indian tests, calling them a serious blow to the nonproliferation regime and a threat to international peace and security.31 The United States imposed sanctions immediately after the tests. At the same time, Washington initiated negotiations with New Delhi to explore opportunities for a better relationship between the two countries. The multiple rounds of talks between Indian Foreign Minister Jaswant Singh and U.S. Undersecretary of State Strobe Talbott were an effort to rope India into the prevailing international nuclear order.32 Soon after the 1998 tests, there were already suggestions that India should be enticed with civilian technology to adhere to nonproliferation norms.33 The United States always evaluated developments in the Indian nuclear program with China in the focus and looked the other way as India developed nuclear weapons. Despite the U.S. desire to contain China, India always adopted a cautious approach. It sought strategic partnership and entered into multiple agreements with the United States to develop its national power, but refused to play the part against China as desired.

India managed to break into the international nuclear nonproliferation regime and normalized its nuclear weapons capability in a unique manner. It convinced the United States to acknowledge India’s status as a “responsible state with advanced nuclear technology;”34 to offer a nuclear deal that facilitated an NSG waiver, without India being an NPT signatory; and to allow international nuclear trade with India outside the NPT framework.

It is noteworthy that the existing nuclear nonproliferation regime successfully put in place stringent measures to stop further proliferation of nuclear weapons. The policy of selective application of rules and political expediency creates unnecessary exceptions, however, that dilute the overall impact of vital components of the international security system.

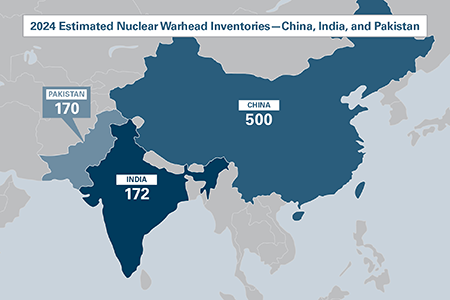

Whether the Indian nuclear program is aimed at China or Pakistan or both countries is not easy to distinguish; it is rather a complex debate about a trilemma that will remain unsettled. How India can manage its deterrence equation with China and Pakistan simultaneously will remain a puzzle. India has shown an inability to confront China openly while dismissing Pakistan as not worthy of attention. This has been evident from Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s letter to U.S. President Bill Clinton at the time of the 1998 nuclear tests and in the ongoing Indian-U.S. partnership where India refuses to be an ally and insists on being only a partner without explicitly mentioning China.

Strategically, India has not been able to achieve what it desired. Although India introduced nuclear weapons into the region, it possibly had not imagined a situation where it could think of a regional nuclear rival. With the NSG in place after the 1974 Indian tests, it was believed that there was little possibility of any further country crossing the nuclear threshold.

To India’s surprise, Pakistan not only initiated a nuclear program, but quickly caught up with India in the acquisition of nuclear weapons.

Had India not tested nuclear weapons in 1974, Pakistan would not have developed its nuclear weapons program with the same zeal and enthusiasm as it did. Had India not tested in 1998, Pakistan would never have tested its nuclear weapons even if it had successfully developed its nuclear weapons capability. India, in pursuit of international prestige or motivated by domestic politics, has created a permanent situation of disadvantage for itself where its conventional superiority is meaningless against a nuclear-armed Pakistan.

ENDNOTES

1. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, World Armaments and Disarmament: SIPRI Yearbook 1975 (London: The MIT Press, 1975), p. 16.

2. Srinivas Laxman, “Bomb or Peaceful Explosion? 50 Years On, Smiling Buddha Remains a Mystery,” Times of India, May 18, 2024.

3. Hans M. Kristensen et al., “Indian Nuclear Weapons, 2024,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol. 80, No. 5 (2024): 326-342.

4. David Hart, Nuclear Power in India: A Comparative Study (London: Allen and Unwin, 1982).

5. Gabrielle Hecht, “Negotiating Global Nuclearities: Apartheid, Decolonization, and the Cold War in the Making of the IAEA,” Global Power Knowledge: Science, Technology, and International Affairs, Vol. 21, No. 1 (2006): 47.

6. George Perkovich, India’s Nuclear Bomb: The Impact on Global Proliferation (New Delhi: Oxford, 1999), p. 30.

7. Onkar Marwah, “India’s Nuclear and Space Programs: Intent and Policy,” International Security, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Fall 1977): 98.

8. Zia Mian, “Homi Bhabha Killed a Crow,” in The Nuclear Debate: Ironies and Immoralities, ed. Zia Mian and Ashis Nandy (Columbo: Regional Centre for Strategic Studies, 1998), p. 12.

9. International Panel on Fissile Materials, “Global Fissile Material Report 2010,” 2010, pp. 117-118, https://fissilematerials.org/library/gfmr10.pdf.

10. Bhabha’s speech at the inauguration mentioned that plant was completed in February 1964 and the first active fuel element was loaded in June 1964, when the plant began fully operating. This is also corroborated with evidence from U.S. intelligence accounts from the time. See P.K. Iyengar, “Briefings on Nuclear Technology in India,” 2009, p. 38, https://newenergytimes.com/v2/library/2009/2009Iyengar-Briefings%20on%20Nuclear%20Technology.pdf; Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), Homi Jehangir Bhabha on Indian Science and the Atomic Energy Programme: A Selection (Mumbai: TIFR, 2009), p. 175.

11. Stuart W. Leslie and Indira Chowdhury, “Homi Bhabha, Master Builder of Nuclear India,” Physics Today, Vol. 71, No. 9 (September 2018): 53-54. See also “Edward Durell Stone Dead at 76; Designed Major Works Worldwide,” The New York Times, August 7, 1978.

12. Satu Limaye, U.S.-Indian Relations: The Pursuit of Accommodation (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1993), pp. 93-136.

16. Jagdish P. Jain, Nuclear India, Vol. II (New Delhi: Radiant Publishers, 1974), p. 169.

20. Robert Gillette, “India: Into the Nuclear Club on Canada’s Shoulders,” Science, Vol. 184, No. 4141 (1974): 1053.

24. Sharon Squassoni, “Looking Back: The 1978 Nuclear Nonproliferation Act,” Arms Control Today, Vol. 38, No. 12 (2008).

25. Pearl Marshall, “India and France Renew Old Friendship,” Nucleonics Week, July 4, 1985.

26. Ann Maclachlan Hibbs Mark, “India Can’t Count on France for Tarapur Fuel Past 1993,” Nucleonics Week, April 16, 1992.

27. “Hyderabad Reactor Begins Using Uranium From China,” Business Line, February 20, 1995, p. 9.

28. Perkovich, India’s Nuclear Bomb, pp. 367-374.

29. John F. Burns, “India Sets 3 Nuclear Blasts, Defying a Worldwide Ban; Tests Bring a Sharp Outcry,” The New York Times, May 12, 1998.

30. Zafar Iqbal Cheema, Indian Nuclear Deterrence (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 1.

31. “The Birmingham Summit: Final Communique,” D/98/8, May 17, 1998, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/api/files/document/print/en/doc_98_8/DOC_98_8_EN.pdf.

32. Himadeep Muppidi, “Colonial and Postcolonial Global Governance,” in Power in Global Governance, ed. M. Barnett and R. Duvall (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 289.

33. Christopher Warren, David A. Hamburg, and William J. Perry, Preventive Diplomacy and Preventive Defense in South Asia: The U.S. Role (Stanford, CA: Stanford University and Harvard University, 1999).

34. Office of the Press Secretary, The White House, “Joint Statement Between President George W. Bush and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh,” July 18, 2005, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2005/07/20050718-6.html.

Nasir Hafeez is director of research at the Strategic Vision Institute in Islamabad.

Division within the Global South makes it more difficult for states favoring legally binding autonomous weapons systems regulation to achieve consensus.

November 2024

By Alexander Hoppenbrouwers

Since the start of the war in Gaza, an Israeli artificial intelligence (AI) system called Lavender has assisted the Israel Defense Forces target selection. Describing Lavender’s approach to this assignment, an Israeli intelligence officer said, “The machine did it coldly. And that made it easier.”1

The Lavender system is a prime example of what many experts are warning against: a developed economy using its technological advantages by deploying AI-powered weapons systems against a Global South adversary, thus expanding the scale on which it can unleash destruction. Analysts often point to this scenario to suggest that Global South countries should be united in aiming to restrict autonomous weapons systems to the greatest extent possible.2

Ongoing diplomatic efforts present a different picture. Several Global South countries are hesitant to restrict the use of autonomous weapons systems or even oppose outright legally binding rules to regulate them. An analysis of their positions suggests that the specific geopolitical situation of these countries is a stronger determinant of their approach to autonomous weapons systems than their status as part of the Global South. Understanding the motivations of these countries is not only crucial for diplomats working on the autonomous weapons topic, but it also provides insight into how international negotiations might evolve in the coming years. This evolution will have important ramifications for how wars in the 21st century will be fought.

International discussions on autonomous weapons systems have been held mainly in the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons group of governmental experts on autonomous weapons systems. Precursors of this group have discussed autonomous weapons systems since 2014. The group has struggled to make progress due to its consensus-based decision-making, allowing individual states to block any decisions. Action has shifted therefore to new venues: for instance, Austria has spearheaded efforts to move discussions on autonomous weapons systems to the UN General Assembly.3

At the same time, several crucial stakeholders have refused any move away from the experts group as the appropriate forum for these discussions. Although not all Global South states are members of the experts group, several Global South states have taken prominent roles in that process.

Small Global South states tend to consider autonomous weapons systems fundamentally dangerous from legal, humanitarian, ethical, and security standpoints. Calls to start negotiating a strict, legally binding instrument to prohibit some autonomous weapons systems and regulate others as soon as possible are made regularly by large groups of these states. A group of mainly smaller Global South states submitted a draft legally binding protocol during the 2023 session of the experts group,4 and a similar group called for the formulation of elements of a legally binding instrument in its 2024 session.5 At times, such states also explicitly refer to technological differences between the Global South and Global North, called the “digital divide,” for instance when a Palestinian delegation warned that AI-powered systems are likely “to be tested on populations of the Global South.”6

Major powers take nearly the opposite approach. India has stated that existing international law is a sufficient framework to deal with autonomous weapons systems.7 It is already using AI technologies to power swarms of drones, as well as to support intelligence operations.8 China has stated that it supports a ban on autonomous weapons systems, but its description of these systems is so narrow that it excludes those likely to be used on the battlefield.9 This framing allows China to form a unified rhetorical front with smaller Global South countries while avoiding steps toward an effective instrument to ban autonomous weapons systems. Similar to India, China is developing autonomous vehicles and exploring the use of AI technologies to support its weapons systems.10

Middle powers present a more varied picture. As a diplomat from the Philippines involved in the 2023 session of the experts group explained, “While smaller states tend to articulate progressive and principled positions in a more general sense, middle powers tend to have more nuanced positions.”11 Several of these middle states, especially those such as Brazil and Mexico that are further removed from geopolitical hotspots where autonomous weapons systems may be used, have joined the criticisms of these weapons voiced by the smaller Global South cohort.

States closer to conflict areas tend to reject the view that autonomous weapons systems are fundamentally dangerous. Turkey, for instance, does not support the development of new international law related to autonomous weapons systems. It also has pointed to possible positive effects that AI systems could have in decision-making during conflicts.12

Perhaps the best example of the complicated position of some middle Global South powers is Pakistan. Although Islamabad has expressed support for the development of legal restrictions on autonomous weapons systems, its statements frequently accord particular importance to risks related to strategic stability. In 2023, Pakistan stated in the experts group, “Mitigating risks from a humanitarian perspective is well placed. However, they alone cannot be a substitute to recommendations on addressing the security dimension.”13 Yet, Pakistan also is earmarking funds for the use of AI technologies and machine learning by its military.14

This example shows how geopolitics shapes calculations. The risk of conflict escalation is a major concern, and if a legally binding instrument to regulate autonomous weapons systems is not forthcoming, Pakistan prefers to match the autonomous weapons abilities of India, its geopolitical rival.

The idea that the Global South uniformly takes a principled stance in opposition to autonomous weapons systems is thus wrong. Admittedly, opposition to these systems is popular in the Global South. The 120-member Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), for instance, submitted a working paper to the experts group in 2022 that calls for a legally binding instrument on autonomous weapons systems and makes reference to morality and ethics.15 At the same time, the Philippine diplomat stressed that “NAM has not been very active in the [experts group] due to differences in positions among its members.”16

Other Global South states have pushed back against autonomous weapons systems regulations. For instance, the majority of states that voted against or abstained from voting on a 2023 UN General Assembly resolution calling for intensified efforts to regulate autonomous weapons systems were from the Global South.17 Understanding this dynamic requires analyzing the specific geopolitical and technological factors affecting the potential exposure of Global South countries to autonomous weapons systems.

For one thing, cross-regional coalitions are likely to play an important role on specific issues when positions of states from different regions converge. This is already visible, even for issues that at first glance may seem closely tied to a specific region’s interests. For example, the only working paper that made a mention of the digital divide during the 2024 session of the experts group was submitted by six Global North and four Global South countries.18 Figuring out how to build and enlarge such cross-regional coalitions will be crucial for countries to further their positions.

Division within the Global South makes it more difficult for those states favoring strict, legally binding autonomous weapons systems regulation to achieve consensus within the experts group. The group’s current slow pace of progress already has been decried by most participants. The lack of a unified Global South front lessens pressure on the experts group as a whole and is one factor preventing quicker and more effective decision-making.

A gradual shift in Global South positions toward greater acceptance of autonomous weapons systems may be possible. Middle-sized Global South states that are closer to conflict areas, such as the Middle East, tend to be less critical of autonomous weapons systems due to their interest in acquiring them. Because legal prohibitions and regulation of autonomous weapons systems are not forthcoming and the international security environment is becoming more fragile, Global South states increasingly may see a need to acquire autonomous weapons systems as their geopolitical adversaries do the same. This would result in a shift in their positions in the experts group.

Rapid action therefore will be needed if progress is to be made on regulating and prohibiting autonomous weapons systems. In a report released on August 6, UN Secretary-General António Guterres reaffirmed the need for urgent action to preserve human control over the use of lethal autonomous weapons systems.19

Recent efforts to move discussions from the experts group to the UN General Assembly could be promising for the Global South, which is better represented in the General Assembly than the experts group. Even if some Global South states did not support the Austrian initiative, the fact that the General Assembly operates by majority vote rather than consensus means that states that oppose strict, legally binding autonomous weapons systems regulation will be unable to block the Global South’s majority support for strict measures on autonomous weapons systems.

Regional initiatives can complement global discussions. In the Belén Communiqué, the CARICOM Declaration on Autonomous Weapons Systems, and the Freetown Communiqué, regional groupings in the Global South committed to work toward new international law regulating autonomous weapons systems.20 Such regional initiatives make it more difficult for states to change their positions on autonomous weapons systems if their geopolitical situation changes and put pressure on all states in these regions to commit themselves to decisive action. Similar efforts could go further by including some legal measures. For example, already existing nuclear-weapon-free zones could be the inspiration for the creation of zones free of autonomous weapons systems.

In the Gaza conflict, the Lavender system shows the frightening potential of warfare in the 21st century. Many Global South countries have recognized this and have committed to work toward effective autonomous weapons systems regulation and prohibitions. Others, however, prefer to acquire Lavender-like systems of their own. World leaders must act quickly at the regional and global levels to ensure that the full potential of these systems is not unleashed on battlefields inside and outside of the Global South.

ENDNOTES

1. Bethan McKernan and Harry Davies, “‘The Machine Did It Coldly’: Israel Used AI to Identify 37,000 Hamas Targets,” The Guardian, April 3, 2024.

2. For instance, see Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, “Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) Submission to the UN Secretary-General’s Report on Autonomous Weapon Systems,” May 20, 2024, https://www.reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents

/Publications/wilpf-submission-unsg-report-aws.pdf; Charlie Linney and Xiaomin Tang, “AI and Autonomous Weapons Systems: The Time for Action Is Now,” Saferworld, May 15, 2024, https://www.saferworld-global.org/resources/news-and-analysis/post/1037-ai-and-autonomous-weapons-systems-the-time-for-action-is-now.

3. UN General Assembly, “Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems,” A/RES/78/241, December 28, 2023.

4. Convention on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Certain Conventional Weapons Which May Be Deemed to Be Excessively Injurious or to Have Indiscriminate Effects (CCW), “Draft Protocol on Autonomous Weapon Systems (Protocol VI),” CCW/GGE.1/2023/WP.6, May 11, 2023.

5. CCW, “Compilation of Replies Received to the Chair’s Guiding Questions,” CCW/GGE.1/2024/CRP.1, March 1, 2024.

6. State of Palestine, Statement to the Vienna Conference on Autonomous Weapons Systems, n.d., https://www.bmeia.gv.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Zentrale/Aussenpolitik/Abruestung/AWS_2024/Statements/State_of_Palestine_Statement.pdf.

7. Tejas Bharadwaj and Charukeshi Bhatt, “India’s Normative Stance on Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, February 26, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2024/02/indias-normative-stance-on-lethal-autonomous-weapons-systems?lang=en.

8. Antoine Levesques, “Early Steps in India’s Use of AI for Defence,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, January 18, 2024, https://www.iiss.org/online-analysis/online-analysis/2024/01/early-steps-in-indias-use-of-ai-for-defence/.

9. Kelley M. Sayler, “International Discussions Concerning Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems,” CRS In Focus, No. IF11294, February 14, 2023.

10. Sam Bresnick, “China Bets Big on Military AI,” Center for European Policy Analysis, April 3, 2024, https://cepa.org/article/china-bets-big-on-military-ai/.

11. Philippine diplomat, interview with author, Vienna, July 10, 2024.

12. Republic of Türkiye, General statement to the group of governmental experts on lethal autonomous weapons systems, n.d., https://docs-library.unoda.org/Convention_on_Certain_Conventional_Weapons_-Group_of_Governmental_Experts_on_Lethal_Autonomous_Weapons_Systems_(2024)/T

%C3%BCrkiye-CCW_LAWS_GGE-04032024.pdf (meeting held March 4-8, 2024).

13. Permanent Mission of Pakistan to the United Nations Geneva, “Remarks by Ambassador Zaman Mehdi, Deputy Permanent Representative of Pakistan at the Meeting of Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) on Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems (LAWS),” May 15, 2023, https://docs-library.unoda.org/Convention_on_Certain_Conventional_Weapons_-Group_of_Governmental_Experts

_on_Lethal_Autonomous_Weapons_Systems_(2023)/Statement_of_Pakistan_at_GGE_(15

_May_2023).pdf.

14. Zohaib Altaf and Nimrah Javed, “The Militarization of AI in South Asia,” South Asian Voices, January 16, 2024, https://southasianvoices.org/sec-c-pk-r-militarization-of-ai-01-16-2024/.

15. Non-Aligned Movement, Geneva Chapter, “Working Paper by the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela on Behalf of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and Other States Parties to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW),” March 7, 2022, https://documents.unoda.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/WP-NAM.pdf.

16. Philippine diplomat, interview with author, Vienna, July 10, 2024.

17. UN Press, “First Committee Approves New Resolution on Lethal Autonomous Weapons, as Speaker Warns ‘An Algorithm Must Not Be in Full Control of Decisions Involving Killing,’” GA/DIS/3731, November 1, 2023, https://press.un.org/en/2023/gadis3731.doc.htm.

18. CCW, “Addressing Bias in Autonomous Weapons,” CCW/GGE.1/2024/WP.5, March 8, 2024.

19. UN General Assembly, “Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems: Report of the Secretary-General,” A/79/88, July 1, 2024.

20. Latin American and the Caribbean Conference of Social and Humanitarian Impact of Autonomous Weapons, Communiqué, February 24, 2023, https://conferenciaawscostarica2023.com/wp-content

/uploads/2023/02/EN-Communique-of-La-Ribera-de-Belen-Costa-Rica-February-23-24

-2023..pdf; Caribbean Community, “CARICOM Declaration on Autonomous Weapons Systems,” n.d., https://www.caricom-aws2023.com/_files/ugd/b69acc_4d08748208734b3ba849a4cb257ae189.pdf; Regional Conference on the Peace and Security Aspects of Autonomous Weapons Systems: An ECOWAS Perspective, Communiqué, April 18, 2023, https://article36.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Freetown-Communique-18-April-2024-English.pdf.

Alexander Hoppenbrouwers, a researcher on nonproliferation and arms control issues, has completed internships with the Vienna Center for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation, the Dutch Foreign Ministry, and the EU delegation to the United Nations in Geneva.

Nihon Hidankyo was honored for its work reminding people of the horror of nuclear weapons and strengthening the taboo against nuclear use.

November 2024

By Shizuka Kuramitsu

The Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations, also known as Nihon Hidankyo, was awarded the 2024 Nobel Peace Prize for its work reminding people of the horror of nuclear weapons and strengthening the taboo against nuclear use.

Sending a clear pro-disarmament message with its decision, the Norwegian Nobel Committee declared in a press release on Oct. 11 that “[t]he extraordinary efforts of Nihon Hidankyo and other representatives of the Hibakusha have contributed greatly to the establishment of the nuclear taboo. It is therefore alarming that today this taboo against the use of nuclear weapons is under pressure.”

The hibakusha, as the survivors of the atomic and hydrogen bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 and of subsequent nuclear tests are known, “have helped to generate and consolidate widespread opposition to nuclear weapons around the world by drawing on personal stories, creating educational campaigns based on their own experience, and issuing urgent warnings against the spread and use of nuclear weapons,” the Nobel committee added.

Nihon Hidankyo, a national organization comprised of member chapters in 36 of Japan’s prefectures, was established in August 1956 in response to the campaign against nuclear weapons and the 1954 U.S. hydrogen bomb test in Bikini Atoll.

“We pledge our determination to save ourselves and, through our experiences, to save humanity from crisis,” according to the organization’s founding declaration.

Nihon Hidankyo’s main missions have been to ask Japan for compensation for the negative effects that survivors suffered from the atomic bombings and to lobby for a world without nuclear weapons so that no one will ever suffer what they have gone through.

As of March, the average age of the hibakusha was more than 85 years, according to a study by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Because of the shrinking size of the organization and its funding base, Nihon Hidankyo chapters “do not know how long they will be able to continue their activities,” said Jiro Hamasumi, the organization’s assistant director-general at a press conference on Oct. 12.

“We have not yet fulfilled our role until these goals are met. Despite difficulties, we will continue to do our best,” Hamasumi added.

When the prize was announced, disarmament communities and leaders around the world congratulated and thanked Nihon Hidankyo for its tireless work and renewed their commitment to advance disarmament amid rising nuclear threats.

“Reducing the nuclear threat is important, not despite the dangers of today’s world but precisely because of them,” U.S. President Joe Biden said in a statement on Oct. 13. “These nuclear risks erode the norms and agreements we have worked collectively to put in place and run counter to the vital work of today’s Nobel Laureates.”

Jørgen Watne Frydnes, chair of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, said, “One day, the hibakusha will no longer be among us as witnesses to history, but with a strong culture of remembrance and continued commitment, new generations in Japan are carrying forward the experience and the message of the witnesses.”

“They are inspiring and educating people around the world. In this way, they are helping to maintain the nuclear taboo—a precondition of a peaceful future for humanity,” he said.

Nihon Hidankyo was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize several times in the past, according to Jiji press. The award ceremony will take place in Oslo on Dec. 10.

Nobel Peace Prize The Nobel Peace Prize has been awarded 105 times to 142 Nobel laureates (111 individuals and 31 organizations) between 1901 and 2024. This is the seventh time since 1985 that the Norwegian Nobel Committee has recognized organizations and individuals for their disarmament work. Past winners in that category are: International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, “for its work to draw attention to the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons and for its ground-breaking efforts to achieve a treaty-based prohibition of such weapons” (2017); Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, “for its extensive efforts to eliminate chemical weapons” (2013); International Atomic Energy Agency and Mohamed ElBaradei, “for their efforts to prevent nuclear energy from being used for military purposes and to ensure that nuclear energy for peaceful purposes is used in the safest possible way” (2005); International Campaign to Ban Landmines and Jody Williams, “for their work for the banning and clearing of anti-personnel mines” (1997); Joseph Rotblat and Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, “for their efforts to diminish the part played by nuclear arms in international politics and, in the longer run, to eliminate such arms” (1995); and International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, “for service to mankind by spreading authoritative information and by creating an awareness of the catastrophic consequences of atomic warfare” (1985). |

Prior to Israel’s retaliatory attack, President Joe Biden said that the United States would not support Israeli strikes against Iran’s nuclear facilities.

November 2024

By Kelsey Davenport

Israel’s retaliatory strikes against Iran did not target the country’s nuclear program, despite calls from top Israeli officials to strike those assets. Prior to the retaliatory attack, U.S. President Joe Biden said that the United States would not support Israeli strikes against Iran’s nuclear facilities.

Israel targeted Iranian air defenses and missile production facilities in its Oct. 26 attack. Israeli aircraft also struck Parchin, a military site where Iran conducted illicit nuclear activities as part of its pre-2003 weapons program. Iranian media outlets reported that four soldiers were killed in the strikes.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said that the attack “severely damaged” Iran’s missile production capabilities.

In a telephone call with journalists shortly afterwards, a senior Biden administration official said that the United States did not participate in the attack but had encouraged Israel to conduct a “targeted and proportional” response with “low risk of civilian harm.”

The U.S. official said that the Israeli strike “should be the end of this direct exchange of fire between Israel and Iran.”

Iranian officials appeared to downplay the impact of the strikes. The country’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, called for “actions that serve the interests of this nation and country,” but said that it would be up to the government to “convey the power and will” of Iran. Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian said that Iran will respond appropriately but reiterated that it does “not seek war.”

The Israeli strike was a response to Tehran targeting three Israeli military bases with nearly 200 ballistic missiles on Oct. 1. Unlike Iran’s missile attack in April, Tehran did not provide much advance warning for the October strike, which was retaliation for Israel’s attacks against Hezbollah in Lebanon that resulted in the deaths of Hezbollah commander Hassan Nasrallah and Islamic Revolutionary Guard Deputy Commander Abbas Nilforoushan.

Israel, with the support of the United States and others, shot down most of the incoming missiles.

In an Oct. 1 statement posted on the social platform X, the Iranian Mission to the United Nations suggested that Iran’s missile strike was intended to deter future attacks by Israel. The statement said that if Israel retaliated for the Iranian strike or committed “further acts of malevolence,” it would face a “subsequent and crushing response.”

Netanyahu will likely continue to face pressure to attack Iran’s nuclear program even if Tehran does not retaliate for the Oct. 26 attack.

In an Oct. 1 statement, former Prime Minister Naftali Bennett said that Israel must “act now to destroy Iran’s nuclear program.” Israel has the tools and the justification and should not “settle for Iranian military bases,” Bennett said.

Although Israel could strike Iranian nuclear facilities without U.S. support, it would be challenging for Israel to destroy deeply buried sites, such as the Fordow uranium-enrichment facility, without the GBU-57 Massive Ordnance Penetrator, the largest conventional weapon in the U.S. arsenal.

A strike against the nuclear infrastructure could also backfire in the long run. Iranian officials have threatened to develop nuclear weapons or withdraw from the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty if the country’s nuclear facilities are attacked. (See ACT, June 2024.)

Biden, like his predecessors, has stated that he would use military force to prevent Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon. Although the country’s nuclear program is advancing, the U.S. intelligence community continues to assess that Iran is not pursuing nuclear weapons development. Following the Oct. 1 attack, CIA Director William Burns said that there is no evidence that Iran’s leadership has made the decision to develop nuclear weapons. Speaking at a conference on Oct. 7, Burns said the United States is “reasonably confident” that it would detect weaponization efforts early on.

A North Korean official said the election will not influence its approach to engagement with the United States and blamed Washington for escalating regional tensions.

November 2024

By Kelsey Davenport

North Korea suggested that the U.S. presidential election will not influence its approach to engagement with the United States and continued to blame Washington for escalating tensions on the Korean peninsula.

Speaking at the United Nations on Sept. 30, Song Kim, North Korea’s representative to the world body, said that “whoever takes office,” North Korea will deal only with “the state entity called the [United States].” He suggested that “the mere administration” does not affect the hostile U.S. policy toward North Korea and Pyongyang’s policy toward Washington.

Kim noted that North Korea can “choose either dialogue or confrontation” but should “go further” in preparing for conflict because of Washington’s aggression in the region.

Despite Kim’s suggestion that dialogue is an option, North Korea’s growing military ties with Russia, its focus on expanding aspects of its nuclear weapons program, and its rejection of unification with South Korea indicate that Pyongyang may not be interested in negotiating with the United States at this time.

Kim said the security situation on the Korean peninsula will be “intricately complicated through to the next generation” unless the United States and its unspecified “followers” change their “confrontation and aggressive nature.”

As North Korea continues to expand its nuclear weapons program, South Korea also is investing in new military systems.

At a parade commemorating Armed Forces Day on Oct. 1, South Korea displayed a new ballistic missile, the Hyunmoo-5, which is the most powerful ballistic missile in the country’s arsenal. It is designed to strike hardened targets with a large conventional warhead. South Korea has tested the system, but has not provided any details on the range and payload.

In addition to displaying the new missile system, President Yoon Suk Yeol heralded the establishment of South Korea’s new Strategic Command. In his Oct. 1 speech, Yoon described the creation of this command as “a key national task” and said it will protect South Korea from “North Korea's nuclear and weapons of mass destruction threats.”

South Korea began developing the new command in 2022 to centralize the country’s responses to North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. It will oversee South Korea’s three-axis defense system, which includes preemptive strikes to thwart North Korean nuclear or missile attacks, known as Kill Chain; multilayered missile and air defenses to intercept North Korean launches; and a counteroffensive strategy known as Korea Massive Punishment and Retaliation.

Yoon said the establishment of its Strategic Command “integrates our military’s advanced conventional capabilities” with U.S. extended deterrence.

The U.S. Strategic Command will coordinate with South Korea’s Strategic Command as part of Yoon’s April 2023 agreement with U.S. President Joe Biden to strengthen South Korea’s role in U.S. extended deterrence.

A U.S. B1-B bomber participated in the Oct. 1 parade, prompting criticism from North Korea.

In a statement ahead of the parade, the state-run Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) accused the United States of “chronic nuclear phobia” and trying to “permanently deploy strategic assets” on the Korean peninsula to put pressure on North Korea.

The B1-B bomber is no longer a nuclear-capable system, but a U.S. Ohio-class submarine, which carries nuclear-armed ballistic missiles, made a port call in South Korea in 2023. In July 2024, South Korea and the United States announced new deterrence guidelines, which Yoon’s government described as specifically assigning U.S. nuclear weapons missions on the Korean peninsula.