Volume 17, Issue 6

October 29, 2025

The 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) expires on Feb. 5, 2026, and yet the United States and Russia have not begun serious negotiations on a follow-on arms control agreement. For nearly two years, during the administration of former President Joe Biden, the chief impediment to talks was Russia’s stance that it would not negotiate with the United States on nuclear arms control while Washington maintained support for Kiev’s self-defense against the Russian full-scale invasion that began in February 2022.

But ever since President Donald Trump’s election, Russia’s position has softened as the new U.S. administration changed its tone on Ukraine. This shift has exposed a different, significant barrier to negotiation of a follow-on treaty: the vocal chorus of defense analysts and officials who are arguing in favor of greater or lesser expansions of U.S. strategic forces to counter China’s nuclear build-up. This build-up dates back to the latter years of the first Trump administration but was only revealed publicly in mid-2021.

Proponents of a U.S. build-up say Washington should prepare immediately to upload more nuclear warheads to its existing strategic delivery systems. Some support expanding the number of delivery vehicles by reverting changes to bombers and submarines made under New START to comply with the treaty’s cap on deployed launchers. The most ambitious proposals recommend expanding the modernization program by procuring more next-generation B-21 bombers and Columbia-class ballistic-missile submarines, while planning to deploy more Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs).

In December, Congress directed the Pentagon to provide plans for reducing the time needed to upload additional warheads to the existing ICBM force, among other measures to prepare the United States to expand the number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads for the first time in some 35 years.

But the arguments for uploading more warheads or otherwise expanding the U.S. nuclear force have not been sufficiently critically examined.

This issue brief provides responses to some of the most common arguments for expanding the United States’ deployed strategic arsenal, ahead of Trump’s planned Oct. 30 meeting with his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in South Korea.

Before leaving for Asia, Trump said he hoped to discuss arms control with Xi during their meeting. There is a path for strategic nuclear relations with China, described in this brief, that could help the United States avoid an arms race while still managing competition with China on favorable terms.

Claim: without more warheads, the United States will not be able to credibly deter China with nuclear threats

Claim: without nuclear threats, the United States cannot deter China

Claim: without expanding its nuclear forces, the United States will be vulnerable Chinese or Russian strategic attack

Claim: the United States should increase its nuclear forces for bargaining leverage in arms control talks

Claim: an arms race would be relatively cheap because the risks of an open-ended upward spiral are limited

An Alternative: Re-framing Options for Managing China’s Build-Up

Claim: without increasing its total number of nuclear warheads, the United States will not be able to issue nuclear threats to deter or defeat Chinese aggression, against Taiwan for instance, while retaining enough warheads to deter other adversaries.

The number of nuclear weapons that the United States needs is driven not just by adversary capabilities and intentions, but also by U.S. policy choices regarding the missions for the employment of nuclear forces. These missions should not only be desirable as tools for advancing national goals while preserving strategic stability but should also—at minimum—be feasible. Over time, as China expands its nuclear force, the mission of defeating Chinese aggression with limited nuclear use—or threats of limited nuclear use—while limiting damage to the U.S. homeland will slip further from feasibility.

Damage limitation—the ability to limit damage to one’s homeland by destroying adversary nuclear forces in a counterforce attack before they can launch or while they are inbound—leads to a mechanistic connection between enemy targets and U.S. force requirements. To an extent, a one-for-one requirement can be avoided by substituting nuclear attacks with conventional strikes, efficient targeting of critical points in a command-and-control system, achieving a qualitative edge in missile lethality, or building up missile defense.

Both the Biden administration’s 2022 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) report and the first Trump administration’s equivalent report from 2018 state that “if deterrence fails,” the United States will attempt “to end any conflict at the lowest level of damage possible.” The 2018 report continues: “U.S. nuclear policy for decades has consistently included this objective of limiting damage if deterrence fails.”

A critical uncertainty is whether this guidance—which will likely be superseded by new policies under the Trump administration—requires the United States to maintain a damage limitation capability against China, or China and Russia simultaneously. Further, it is unclear how demanding either Biden or Trump was or will be, respectively, in setting requirements for damage limitation ambitions.

Proponents of an ambitious damage limitation capability justify this as necessary to give the United States more freedom to take escalatory steps in a crisis—particularly one in which stakes are asymmetrical. Those escalatory steps could include crossing or threatening to cross the nuclear threshold with either limited tactical strikes or a massive strategic attack while confident that the United States will come out better-off.

In plain language, an ambitious damage limitation requirement gives the United States the freedom to threaten the first use of nuclear weapons – or at least to increase the credibility of U.S. threats to do so.

While China’s nuclear force remained small, the ability of the United States to conduct a damage-limiting strike did not justify an obvious increase in U.S. force numbers or, therefore, require agreement among Pentagon bureaucrats and political appointees that damage limitation should be named as an explicit mission for nuclear forces. But with the size of China’s nuclear force growing—driven at least in part by Beijing’s desire to preserve an assured retaliatory nuclear strike capability in the face of what China views as increasingly capable U.S. conventional and nuclear strike and missile defense capabilities—that conversation has burst into public.

However, China’s nuclear forces have now considerably built up, casting doubt that the United States could successfully limit damage to itself against a Chinese retaliation, even if Trump decides to upload warheads in the near term. At a minimum, it is doubtful Washington could forever credibly convince Beijing that it had that capability.

Successful damage limitation, under one definition, requires “the ability to deny an adversary the ability to inflict unacceptable damage as defined by the adversary.” Traditionally, Chinese leaders believed that unacceptable damage required only a “small number” of warheads to successfully arrive at their targets. The Pentagon argues that the size of China’s force currently under construction suggests a desire to be able to guarantee delivery of more warheads to their targets, but this remains disputed.

A nuclear exchange model published in 2020 forecast that in 2025, China would have a more than 90% chance of successfully delivering a nuclear warhead to the U.S. homeland after absorbing a counterforce strike when at full alert, and a 40% chance of the same when on normal day-to-day alert. That study was based on estimates of Chinese force growth before the revelation of new missile fields and therefore likely underestimates the future ability of Chinese forces to retaliate against the United States.

If China moves toward adopting a launch on warning posture, building out a reliable early-warning system that will permit it to launch silo-based intercontinental missiles on detection of a U.S. first strike, significant damage limitation will become even more difficult. The United States would have to rely on advance attacks on China’s nuclear command and control system to prevent silo-based missiles from launching while U.S. warheads are inbound.

This would mean either (or more likely, a combination of) kinetic strikes using conventional missiles or exquisite cyberattacks and electronic warfare. Both types of attacks have inherent problems: conventional missile attacks would be abundant during all phases of a war, and misinterpretation of intentions could plausibly lead to China launching its missiles prematurely out of fear of U.S. escalation; non-kinetic options are hard to credibly make threats with, and once exposed may be mitigated through adversary adaptation.

But fundamentally, defining successful damage limitation in terms of the criterion necessary to dissuade an enemy is a risky endeavor. No analyst can guarantee that even if U.S. damage limitation capabilities are good enough to deny China its self-defined ability to inflict unacceptable damage, China could be convinced, or—under circumstances of extreme stress—Xi would not make an irrational move and call our bluff regardless.

Claim: without the ability to threaten nuclear use against China, the United States will not be able to deter a Chinese invasion of Taiwan.

By far the most important deterrent of a takeover of Taiwan is the difficulty of an invasion. As the Pentagon noted in the latest issue of its annual report on Chinese military capabilities, a “large-scale amphibious invasion would be one of the most complicated and difficult military operations for the PLA.”

The most commonly proposed use case for U.S. nuclear weapons in an invasion scenario would be to destroy Chinese troops landing on Taiwan if U.S. forces have been dealt a severe blow by the People’s Liberation Army already and cannot prevent or repel a landing in force.

But there are ways by which Taiwan, with the help of the United States, could improve its conventional forces to make an invasion more difficult, such as acquiring more anti-ship and anti-air missiles as well as sea mines and other cheap weapons. Many of these would be more cost effective than pursuing an open-ended strategic nuclear arms race to maintain the U.S. freedom to make nuclear threats at will.

Further, there are other Chinese military intervention scenarios in which U.S. threats to use nuclear weapons would not be credible. For instance, if China were to forgo an invasion and attempt to coerce Taiwan through an extended missile strike campaign or a naval blockade, the United States might find it difficult to convince China that it would use nuclear weapons in response. Of course, China may avoid overt military means altogether and continue favoring its ongoing campaign of political, economic, and military pressure below the conflict threshold.

Beyond the inherent difficulties of an invasion, the second-most important deterrent is the perception of a plausible U.S. commitment to support Taiwan. Maintaining the traditional U.S. policy of ambiguous but implied support for Taiwan remains critical.

Finally, it is important to ask whether we fully understand the negative repercussions of U.S. first use of nuclear weapons to stop a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. Even if the predictions of proponents of first use are correct and Beijing were to back down after one or two detonations, the nuclear taboo would have been broken. The consequences are unpredictable and could include a world of frequent tactical nuclear use, widespread proliferation, and additional international opprobrium heaped on the United States.

Claim: without increasing its nuclear force, the United States could become vulnerable to a future larger Chinese force, or a joint Chinese-Russian nuclear first strike.

Some U.S. officials have expressed skepticism that China will maintain its traditional no first use policy in the context of a general conflict with the United States. Under this view, China may see opportunities to use limited nuclear strikes to defeat U.S. forces on or around Taiwan.

China might feel it necessary, according to some skeptics, to greatly further expand its strategic forces in order to itself have escalation dominance over the United States, adopting the same logic as U.S. strategic planners and seeking its own damage limitation capabilities.

The evidence for such a Chinese approach is weak. Not only is it contrary to the historical Chinese approach to nuclear weapons policy, it is also simply very difficult to limit the retaliatory capabilities of the United States. With a secure second-strike force at sea—which China does not have due to inferior submarine technology—and hardened silos coupled to a robust early warning system, the United States is well placed to survive a counterforce first strike.

Going even further, some argue that Moscow and Beijing could coordinate nuclear operations and launch a joint first strike against the United States. There is no evidence such coordination is happening, and logically the temptation for either side to ‘cheat’ and allow the other to suffer the full brunt of U.S. retaliation would be enormous. In a post-U.S. world, China and Russia would once again pose the greatest long-term threats to each other, and leadership in both capitals would be thinking forward to the day after a nuclear war.

Claim: the United States should increase its nuclear forces in order to have bargaining leverage in future arms control negotiations.

The United States does not have substantial capacity to expand its nuclear modernization program over the next decade to create additional bargaining leverage. The National Nuclear Security Administration is already simultaneously managing seven nuclear weapons programs, while the Department of Defense is struggling to deliver new ICBMs and ballistic missile submarines on time and under budget.

The United States already has substantial bargaining leverage that it can put on the table in negotiations with Russia on a follow-on to New START. For example, the Trump administration’s substantial plans to expand U.S missile defense capabilities, which would have a significant effect on the strategic balance even if not fully implemented, are a key driver of Russian and Chinese fears. Pre-Golden Dome missile defense plans, such as the expansion underway of the U.S. Ground-Based Midcourse Defense system, would also be valuable bargaining chips.

Previously, Republican opposition to negotiated limits on U.S. missile defense systems was a serious bar to using U.S. missile defense as leverage in arms control negotiations. The pliability of Senate Republicans to the president’s political pressure, however, may upset what was previously conventional wisdom. To further defuse opposition to missile defense restrictions, the United States should insist on parallel limits on adversary missile defense systems as part of any new framework.

Claim: Embracing an arms race would be relatively cheap because the risks of an open-ended upward spiral are limited.

Proponents of a near-term upload of warheads to existing U.S. delivery systems argue that this would not destabilize the strategic balance in a way that leads to long-term arms racing. They argue that Russia would not need additional forces to hold the U.S. force at risk because the number of targets would not increase, while the United States could use the additional warheads to cover the new Chinese targets.

It is not clear that Russia would choose to accept numerical inferiority to U.S. nuclear forces simply because the number of U.S. targets remains unchanged. There are at least three reasons to doubt that Russia will exercise restraint. First, Russia prides its status as a leading nuclear power and is unlikely to accept a position of inferiority simply because it is convenient for U.S. strategic planning.

Second, Russia is in the final stages of a decades-long strategic modernization program, replacing siloed, sea-based, and road-mobile platforms. A senior U.S. Air Force general said Aug. 27 that the Russian strategic modernization effort has not been disrupted by the war, noting that “the monies that they put to their nuclear deterrent still go there and that has priority.” In the absence of New START limits, Moscow could choose to increase the number of strategic missiles it produces by simply running production lines a few more years.

Third, the United States still holds a potential upload advantage over Russia. According to estimates by the Federation of American Scientists, the United States could upload just short of 2,000 warheads on existing delivery systems, while Russia only could upload about 1,100. Russia might choose to produce more missiles in order to close that gap.

An Alternative: Re-framing Options for Managing China’s Build-Up

As a competitive strategy, improving Taiwan’s conventional capability to prevent a hostile invasion is superior to committing to an open-ended arms race. Rather than pursuing a brittle and fleeting capability to threaten nuclear use with impunity, the United States should accept the reality of mutual vulnerability with not only its traditional nuclear peer, Russia, but also China. This is the most important reassurance the United States could offer China at the early stages of re-engagement on nuclear risks. If President Trump wants to achieve results on “denuclearization,” he should proceed from the principle that lowering the risk of nuclear war with China is more important than manipulating nuclear fears to maintain general deterrence.

Instead of persisting at involuted mind-games centered on manipulating the risk of nuclear war, President Trump should engage his counterpart, President Xi, on China’s proposal for a joint no-first-use agreement and push for a substantive discussion of how to make such an agreement credible. Many U.S. officials have expressed doubt that Chinese leaders would respect its own no-first-use policy in a real-world crisis with the United States. For its part, China has reasons to believe the United States would also consider using nuclear weapons first in a conflict under certain conditions. The two sides should acknowledge their mutual vulnerability to nuclear attack and explore the changes to force posture and limits to systems that would make no-first-use policies robust and credible.

Minimizing fear of a disarming or significantly damage-limiting first strike would attenuate at least one powerful Chinese incentive to continue building up its strategic nuclear forces. Even though Xi might still desire a larger arsenal for reasons of prestige or a sense that it creates strategic leverage, with reassurances on offer Trump would at least have a better chance of convincing him to cap the Chinese force before it reaches parity with the United States.

In addition, if Putin and Trump show restraint by agreeing to respect the central limits of New START for at least another year and resume bilateral U.S-Russian strategic stability and arms control talks, they could invite China, France, and the United Kingdom to reciprocate by freezing their nuclear forces at the current number of strategic nuclear launchers.

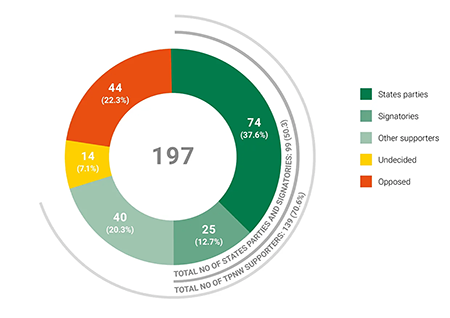

According to independent assessments by the Federation of American Scientists, the United States and Russia have fewer than 800 total strategic nuclear launchers each; China has some 550 strategic nuclear launchers; and the U.K. and France have a combined total of 96 strategic launchers.

A mutual freeze in the number of strategic nuclear launchers at these levels would not adversely affect any one country’s nuclear deterrence capabilities. A freeze would create some much-needed predictability and provide a basis for serious bilateral talks on further nuclear restraint and reductions.—XIAODON LIANG, senior policy analyst