Will India and Pakistan Ever Join the Nuclear Suppliers Group?

November 2024

By Mark Hibbs

The Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), the world’s leading multilateral nuclear export control arrangement, will be 50 years old in 2025. In advance of this occasion, some observers and officials among the participating governments have suggested that the group prioritize discussions about expanding the NSG membership, prompted by applications from India and Pakistan that have been awaiting decisions for several years. It is possible that such an exercise already is underway in internal and informal policy circles; official NSG public statements about recent annual plenary meetings note tersely that consideration of pending applications and India’s relationship to the NSG in particular is ongoing.1

The lack of action is long-standing. Although India and Pakistan filed separate, formal applications for NSG membership in 2016, the group never reached consensus on either candidate country. This followed 15 years during which the NSG wrestled with the topic of expanding membership, with the Indian prospect proving especially contentious. The global political environment today is different than it was a decade ago, generating speculation that, with China’s cooperation, a renewed membership effort by India and Pakistan could succeed.

Nevertheless, barring unforeseen developments, it is unlikely that the NSG participating governments will actively promote including India or Pakistan anytime soon. That will not happen until the members are confident that both countries will embrace and help sustain the group’s export control and nonproliferation mission. Influential NSG members suggest that India and Pakistan must work harder to reach this standard. Moreover, a decision to admit either or both states must be predicated on an understanding within the group about what the requirements should be for admitting new members.

The NSG sets the nonproliferation ground rules for the world’s nuclear trade, and the more universal adherence to its guidelines is, the greater the effectiveness. In principle, the nonproliferation regime would benefit from including India and Pakistan in the NSG because both states possess significant nuclear assets. Conversely, if their conduct was not consistent with NSG guidelines and principles, the regime could suffer damage.

Considerations about NSG relations with India and Pakistan are playing out at a moment when the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) is under growing stress from challenges by Iran, North Korea, established nuclear-weapon powers, and rising nuclear technology expectations in non-nuclear-weapon states. The nearly universal treaty is the cornerstone of the multilateral regime to control the spread of nuclear arms, but India and Pakistan are not parties.

The responsibility of NSG participating governments to make a sound decision about these candidates is significant and the task challenging because powerful members might intervene in these cases based on whether India and Pakistan are allies or adversaries. China and the United States bear particular responsibility for their roles in the decision-making.

NSG Beginnings

The 48 NSG members govern global nuclear trade worth about $15 billion annually by implementing two sets of guidelines for the export of nuclear-related items. The first set refers to items specially designed or prepared for nuclear use, and the second set concerns dual-use items and technologies related to the nuclear fuel cycle and nuclear weaponization.

Governments participating in the NSG, a voluntary mechanism, authorize transfers of listed items for nuclear use according to formal governmental assurances from recipient states. These assurances, for example, exclude the use of transferred items in nuclear explosives and stipulate that the items will be subject to peaceful-use verification. There is a “close interdependence” between the first set of guidelines and the comprehensive safeguards of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). “Almost all refusals by NSG participants of applications for export licenses have concerned states with unsafeguarded nuclear programs.”2

Deciding whether to include India and Pakistan as members is a challenge for the NSG from several perspectives. The historical record of multilateral nuclear trade controls for most of the last half century implies that, for the suppliers to admit India or Pakistan, many must revise their proliferation risk assessment concerning these states, which was formed during decades of effort by India and Pakistan to defy and defeat NSG export controls.

The NSG was created in 1975 by the world’s nuclear technology-holding countries (Canada, France, Japan, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, the United States, and West Germany) in direct response to India having conducted its first nuclear explosive test one year earlier. To achieve this feat, India used items that it obtained from Canada and the United States under bilateral agreements for peaceful nuclear cooperation.

During the same time period, Pakistan was quietly preparing to go forward with secret nuclear activities that would allow it to match India, its main adversary, should that country obtain nuclear arms. Accordingly, from the beginning, the NSG has viewed India and Pakistan as principal targets of the group’s overall effort to restrict and deny trade in nuclear equipment, dual-use items, materials, and technology on the grounds that the two states are proliferation risks.

India’s 1974 test challenged nuclear suppliers by underscoring the essential dual-use nature of nuclear equipment and materials, which can be used for peaceful and nonpeaceful purposes. In this case, India made and detonated an explosive device using plutonium that it separated from uranium fuel it irradiated in a reactor supplied by Canada. Operation of the reactor, specifically moderating the nuclear reaction in the core, relied on heavy water that the United States supplied to India.

India claimed that its explosive nuclear test was not for a nuclear bomb but for a “peaceful nuclear device.” This designation may have been permitted by Canada’s agreement with India for supply of the reactor in 1954, but according to declassified U.S. government documents, such use was expressly disallowed by the U.S. agreement with India for the supply of the heavy water. “Development of [a peaceful nuclear explosion would be] tantamount to development of nuclear weapons,” the U.S. Department of State informed the embassy in India four years prior to the test.3 The United States was satisfied that Pakistan, in response to the Indian test, was preparing to embark on its own nuclear weapons development as part of its nuclear energy program.4

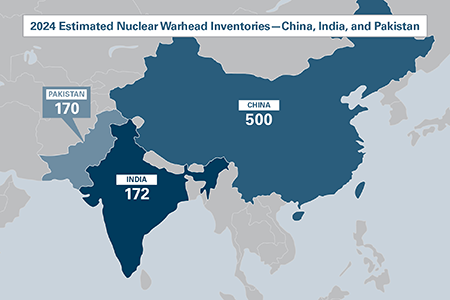

Thereafter and even now, nuclear supplier states in the NSG restricted exports of nuclear items to India and Pakistan, especially highly sensitive items such as those needed for uranium enrichment and fuel reprocessing. India and Pakistan independently continued to develop their nuclear technology and nuclear materials-processing capacities, including through nuclear trade carried out in defiance of NSG guidelines for participating governments and their suppliers. In May 1998, India and Pakistan each conducted a series of nuclear explosive tests and then declared themselves nuclear-armed states.

The NPT Conundrum

The nuclear weapons-testing achievements of India and Pakistan defied the 1995 indefinite extension of the 1970 NPT, which excluded India from a list of five states it identified as lawful possessors of nuclear arms. The tests also alerted nonproliferation-minded powers that Indian and Pakistani nuclear capabilities must be taken seriously.

That message was not lost on the Republican leadership in the United States. Even before President George W. Bush took office in January 2001, his designated cabinet members were preparing to initiate civilian nuclear cooperation with India, which had been blocked by U.S. law enacted in response to India’s 1974 nuclear blast. Bush and Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh went on to include nuclear energy in a bilateral framework agreement toward a “strategic partnership,” in which the United States viewed India’s democratic aspirations and growing economic, technological, and military power as a counterweight to an increasingly formidable China.

On a parallel track, the NSG in 2001 adopted guidelines for participating governments to consider when evaluating the credentials of future NSG membership candidates. That step was not a coincidence; some NSG participants anticipated that an increasingly wealthy, technology-endowed, and more ambitious India, supported by the United States including by advancing India’s nuclear energy capacities, would eventually seek NSG membership.

The 2001 NSG candidate guidance included five specific factors that NSG members should consider.5 One strongly advocated factor is that candidate states be in full compliance with the NPT. In 1997 and following the decision by NPT states-parties to extend the treaty indefinitely, the NSG formally singled out the NPT as a critical signpost for a state’s membership qualification. The guidance did not expressly require that a new NSG member be a party to the NPT. It stated instead that NPT participation was one factor “among others,” implying that a candidate might be admitted based on NSG members’ specific considerations, including political considerations. In the background loomed the fact that when the NSG was established a quarter century earlier, it admitted France, at the time a non-NPT state. The net effect of the “factors” statement was to prompt further internal debate about membership criteria for non-NPT states, including what commitments candidates might offer in lieu of NPT compliance.

During subsequent Indian-U.S. bilateral negotiations on civilian nuclear cooperation, the two countries issued joint statements signaling that they favored adjusting international trade rules to facilitate a resumption of U.S. nuclear trade with India. In 2008, NSG members, under pressure from the United States, granted India an exemption from NSG guidelines to accommodate nuclear trade foreseen under the Indian-U.S. bilateral nuclear cooperation agreement. Thereafter, NSG participants discussed and debated the case for future Indian participation in the group; in 2016, India and Pakistan formally applied for NSG membership.

The two applications were not approved by NSG participants. Rafael Mariano Grossi, an Argentine diplomat and former NSG chairman who now heads the IAEA, worked closely with U.S. counterparts to craft a solution that would permit India to join the NSG based on criteria that could apply to all future candidates, including Pakistan.6 One NSG participating government objected to this gambit on procedural grounds, and others surmised that Grossi’s proposal appeared to favor membership for India but not for Pakistan. Since 2018, the NSG has not made any membership decisions, although in the meantime the Indian and Pakistani applications have been joined by applications filed by Jordan and Namibia.

The NSG’s ambiguous 2001 NPT benchmark remains a sticking point for consideration of Indian and Pakistani membership. For the NSG, associating the arrangement with the NPT was a logical step for several reasons. The treaty’s Article I bans nuclear-armed states from assisting others in acquiring nuclear weapons, Article II prohibits non-nuclear-armed states from attaining that same result, and Article III calls for IAEA verification (“safeguards”) to be implemented in states that are party to the treaty “with a view to preventing diversion of nuclear energy for peaceful uses to nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices.” For NSG participants, conditioning trade on the obligations expressed in these first three NPT articles reduced the risk that their commerce would contribute to proliferation.

Washington’s 2008 request for an NSG exception to permit India to import nuclear wares necessitated that the United States apply direct pressure on some NSG participants. That was in part because in 1992 the United States had prompted the group to amend its guidelines to deny nuclear-specific transfers to all non-nuclear-weapon states, formally including India, that did not have comprehensive IAEA safeguards on all their nuclear materials. The logic for that denial rule seemed clear: Nuclear-armed states that are not NPT parties, including India and Pakistan, are not subject to the treaty’s obligations and restraints, thereby increasing the proliferation hazard faced by suppliers from nuclear trade with these states.

India and Pakistan have not joined the NPT for national security reasons, but nuclear leaders in these states also have objected that the NPT is an expression of discrimination by rich, technology-endowed states against poor states with few nuclear resources. The discrimination, in their view, includes the NPT definition of a nuclear-weapon state as one that manufactured and tested a nuclear explosive device before January 1, 1967. This rule permitted China and France, both NSG members, to join the NPT as nuclear-weapon states in 1992. Unlike China and France, India and Pakistan may not join the NPT and retain their nuclear weapons.

For three decades, India deplored the NSG and unilateral trade bans, particularly by Canada and the United States, in response to its nuclear explosive test. India’s attitude began changing during the 2000s as the country sought to forge strategic links to the United States and increasingly identified with the world’s nuclear haves. In the process, Indian policymakers and pundits crafted rationales to justify New Delhi’s desire for NSG membership and to explain to domestic audiences the switch from opposition to support for an instrument that India long considered an unjust cartel.

Pakistan also spent years relentlessly challenging NSG guidelines. When Pakistan confirmed in 2004 that its leading nuclear procurement agent shared the country’s uranium-enrichment know-how, largely stolen from Europe, with clandestine nuclear programs in Iran, Libya, and North Korea, Pakistan was widely deplored. Thereafter, it shifted its posture to embrace nuclear trade controls. Yet, the benefits of NSG membership likely will be fewer than what advocates in New Delhi or Islamabad have hoped or claimed.

The Value of NSG Membership

India and Pakistan have evolved, even reversed, their public diplomacy on nuclear nonproliferation rulemaking. During the first half century following independence in 1947, both states considered nonproliferation a cover for advanced states to deny technology to others. More recently, the Pakistani proliferation revelations; the emergence of China, India’s rival, as a great power; destabilizing nuclear developments in Iran and North Korea; the rise of international terrorism; and nuclear war-posturing by Russia over Ukraine have raised the profile of nuclear proliferation as a policy concern in both South Asian states.7 For good reasons, India and Pakistan today would welcome inclusion in the NSG’s technically focused, multilateral rulemaking discussions concerning the eligibility requirements for participation in nuclear trade and also the specifications for listing controlled items.

Despite this, NSG membership likely would not significantly boost India’s participation in the supply chain for new nuclear energy projects carried out with foreign partners, and it would not be essential to India meeting its climate mitigation targets. In addition, membership likely would not influence India’s access to foreign supplies of equipment, uranium fuel, or engineering services for its safeguarded nuclear power plants. For India, these interests could be addressed through its 2008 NSG waiver, which permits India to import nuclear items for peaceful use from foreign suppliers regardless of NSG guidelines that would otherwise deny that commerce.8

A decade ago, India made plans to set up 12 new nuclear power plants in cooperation with industry in the United States and France. So far, these projects have not materialized on the ground. In the meantime, the cost of nuclear power investments has increased, and U.S. and French firms face capacity and financial challenges that may lead them to prioritize investments carrying less project risk. According to government officials in NSG member states participating in these projects, India’s failure to agree to nuclear liability terms that comport with world standards, not India’s nonmembership in the NPT, is the most significant obstacle to realizing these projects.

Notwithstanding NSG restrictions on nuclear trade, India and Pakistan for many years have benefited significantly from nuclear commerce with NSG supplier states. Until 1992, when the guidelines were amended to require comprehensive IAEA safeguards in recipient non-nuclear-weapon states as a condition of nuclear trade, the NSG permitted suppliers to transfer reactors and other nuclear items to both South Asian states under transaction-specific IAEA safeguards.

On this basis, Russia and China have exported reactors and other items to India and Pakistan, respectively, in some cases with impunity, ignoring the reservations and objections of many NSG participants. Russia brushed off such concerns in supplying fuel for a nuclear power plant in India after 1992 by claiming that failure to supply the fuel would raise safety risks.9 Despite the reservations and objections of many NSG participants, China has exported and continues to export nuclear power plants to Pakistan, claiming that the supply agreements for all these transfers were concluded before 1992.10

Following up on the precedent-setting 2006 Indian-U.S. nuclear cooperation accord and India’s 2008 NSG trade restrictions waiver, India has concluded numerous bilateral nuclear cooperation agreements, including with at least 10 NSG supplier states.11 These agreements in the long term may enable India to obtain from NSG suppliers a broad range of nuclear items that advance its peaceful-use nuclear energy development. The risk that, without NSG membership, suppliers would revoke India’s 2008 waiver is minimal, given the requirement that a consensus of NSG participants would be necessary to take that step.

The Anticipated Chinese-Indian Reset

As 2024 draws toward a close, observers and media in India are speculating about prospects for a coming “reset” in Chinese-Indian relations following more than a decade of heightened bilateral tension that has led to military clashes on their shared Himalayan frontier. With a view toward this anticipated warming diplomacy, “India desperately needs to revive its [NSG] membership efforts,” according to one observer, apparently because India has made no headway since its failed effort in 2016.12

Around that same time, China encouraged Pakistan to file an application for membership in step with India, according to participants. China also made clear that it would not approve India’s membership application without, in effect, opening the way for Pakistan’s membership on the grounds that admitting one non-NPT state alone would discriminate against others unless universal criteria were applied.

Some Indian commentators have expressed hope that China and India can agree to a compromise on this matter. Although the government of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi publicly reaffirmed its resolve to seek NSG membership, this goal is dwarfed by the complex, pressing national security issues that divide Beijing and New Delhi.

Some Indian commentators have expressed hope that China and India can agree to a compromise on this matter. Although the government of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi publicly reaffirmed its resolve to seek NSG membership, this goal is dwarfed by the complex, pressing national security issues that divide Beijing and New Delhi.

In the last eight years, India and Pakistan have embraced very different blueprints for enabling the NSG to expand to include non-NPT states. India has insisted on being admitted based on a state-specific approach considering only India’s qualifications. Pakistan, in line with China’s views, has argued that non-NPT states should be admitted

based on nondiscriminatory criteria that would be applied to all applicants without exception.

As in 2016, some officials and observers argue that admitting only one of them would ensure that that state thereafter would veto membership by its adversary. In theory, NSG participants could agree that if one of the two states were admitted, the new member may not vote against the second state’s application. That procedure, however, would compromise the NSG’s consensus rule for decision-making and, in this case, would affect a decision of watershed importance.

The Geopoliticized Environment

In the past, NSG participants have made important decisions on membership applications by “considering evidence of whether a state will behave in the interest of the nuclear export control regime.”13 This approach also governs the group’s evaluation of membership for India and Pakistan. According to participants, a number of significant supplier states in Europe, North America, and the Asia-Pacific region do not support admitting India or Pakistan now, even though some of these governments have expressed official support in principle for India’s participation.

Between 2016 and 2018, India, supported by the United States, joined three multilateral export control regimes: the Wassenaar Arrangement for munitions and dual-use items, the Missile Technology Control Regime for missiles and related technology, and the Australia Group for chemical and biological weapons-related goods. India viewed its membership in these arrangements as providing credibility for its pending NSG application. These three regimes do not require states’ compliance with the NPT for admission, but India’s performance record in these arrangements has raised concerns at the working level among NSG participating governments about India’s like-mindedness. Inside these regimes, “India has been difficult,” according to one NSG government official, without providing details that are subject to confidentiality rules in all four export control arrangements.

Pakistan’s behavior and status likewise raise questions about whether it is in harmony with the NSG mission. Pakistan is not a member of any of the above-mentioned export control regimes, and it does not have a significant track record in administering nuclear trade controls. There is also the matter of Pakistan’s ongoing nuclear-specific and nuclear dual-use trade with Chinese suppliers.14 In the view of some NSG supplier states, Pakistan is not ready for membership at this time.

For NSG participants, it is axiomatic that like-mindedness concerning the group’s export control and nonproliferation mission is essential for the arrangement to function effectively and credibly. The rise of geopolitical pressures and considerations among weighty participants during the last decade, however, is a challenge to like-mindedness. How can participants assure that their verdicts about like-mindedness are about the group’s mission and not about favoring allies or excluding competitors and adversaries?

Washington’s political advocacy of New Delhi’s membership, India’s balancing act in managing its relations with the West and Russia, and China’s sponsorship of its ally Pakistan all pose challenges to NSG participating governments that should focus decision-making on membership applications as strictly as possible on candidates’ nuclear supply, export control, and nonproliferation credentials.15 The ambiguous language of the 2001 membership guidance document, if not carefully applied, might encourage arbitrariness because it was designed to afford participants flexibility in deciding the basis on which a candidate for membership should be admitted.

The NSG has the biggest membership of all four export control arrangements, and participants have discussed whether further expansion, especially to candidates whose like-mindedness may be considered uncertain, would compromise effectiveness. The NSG mission is nuclear export controls and nonproliferation. In contrast, India’s quest for membership has been driven in part by great-power aspirations and domestic electoral politics. If Modi, who began his third term in June, succeeds in attaining NSG membership for India, his ruling BJP party will eclipse its rival, the Indian National Congress Party, which between 2004 and 2009 under the Singh government achieved India’s nuclear breakthrough with the United States and the NSG waiver.

Beginning in 2022, according to Indian media, New Delhi raised its NSG interest with Beijing and had its foreign minister publicly reaffirm India’s expectations about joining the group. Yet, participants report that the NSG currently feels no pressure from either China, including on behalf of Pakistan, or India to force the pace of decision-making on these two applications.16

As it stands now, a significant number of participants do not favor admitting India or Pakistan. In 2016 by some accounts, China alone prevented India’s membership bid from succeeding. Today, as then, China sits at the fulcrum of any resolution of this issue. Without a Chinese-Indian understanding, neither India nor Pakistan will be admitted.

As importantly, before they will be able to join, India and Pakistan will have to convince all NSG members that they share the group’s mission. That is an undertaking challenged by increasing geopolitical tensions and the legacy of powerful nuclear suppliers making exceptions to the NSG principles and guidelines.

ENDNOTES

1. “Public Statement, Plenary Meeting of the Nuclear Suppliers Group,” June 25, 2021, https://www.nuclearsuppliersgroup.org/images/Files%20and%20Documents/Documents

/Public%20Statements/2021_Public-statement_Brussels.pdf.

2. International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), “Communication Received From the Permanent Mission of the Argentine Republic to the International Atomic Energy Agency on Behalf of the Participating Governments of the Nuclear Suppliers Group,” INFCIRC/539/Rev. 8, July 28, 2022 (hereinafter IAEA INFCIRC/539/Rev. 8).

3. “State Department Telegram 160591 to U.S. Embassy India, 29 September 1970, Confidential,” National Security Archive, September 29, 1970, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/document/29492-document-7-state-department-telegram-160591-us-embassy-india-29-september-1970.

4. “Pakistan and the Non-Proliferation Issue,’’ n.d., https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB6/docs/doc20.pdf.

5. “Procedural Arrangement for the NSG,” NSG Aspen Plenary, May, 2001.

6. Ian Stewart and Adil Sultan, “India, Pakistan, and the NSG,” Kings College London, June 10, 2019, https://www.kcl.ac.uk/news/india-pakistan-and-the-nsg.

7. Mark Hibbs, “Eyes on the Prize: India’s Pursuit of Membership in the Nuclear Suppliers Group,” The Nonproliferation Review, Vol. 24, Nos. 3-4 (2017): 280-283.

9. “TVEL to Supply Fuel Pellets for Tarapur NPP (India),” Rosatom, n.d., https://www.rusatom-energy.ru/en/media/rosatom-news/tvel-to-supply-fuel-pellets-for-tarapur-npp-india/ (accessed October 20, 2024).

10. Mark Hibbs, “The Future of the Nuclear Suppliers Group,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP), 2011, pp. 13-18, https://carnegie-production-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/static/files/future_nsg.pdf.

11. Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, “Foreign Countries Having Nuclear Pact With India,” August 11, 2016, https://www.mea.gov.in/rajya-sabha.htm?dtl/27300/QUESTION_NO2812_FOREIGN_COUNTRIES_HAVING_NUCLEAR_PACT_WITH_INDIA.

12. Moksh Suri, “Can India Revive Its Quest for Nuclear Suppliers Group Membership?” The Diplomat, April 1, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/04/can-india-revive-its-quest-for-nuclear-suppliers-group-membership/.

13. Mark Hibbs, “Toward a Nuclear Suppliers Group Policy for States Not Party to the NPT,” CEIP, February 12, 2016, https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2016/02/toward-a-nuclear-suppliers-group-policy-for-states-not-party-to-the-npt?lang=en.

14. Dinakar Peri, “Chinese Dual-Use Cargo Heading to Pakistan Seized,” The Hindu, March 3, 2024, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/ship-suspected-to-contain-dual-use-consignment-for-pakistans-nuclear-programme-stopped-at-nhava-sheva-port-in-mumbai/article67906937.ece.

15. Increasing geopolitical competition among great-power participants in export control regimes in which India is a member may inhibit transparency and availability of reliable information concerning India’s behavior in these mechanisms. Shortly after joining the Missile Technology Control Regime, India partnered with Russia for joint production of an advanced, long-range cruise missile, a development that was criticized by Western participants who had supported India’s membership. See Nuclear Threat Initiative, “India Missile Overview,” November 4, 2019, https://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/india-missile/. India chaired the 2023 plenary meeting of the Wassenaar Arrangement at a time when, given the backdrop of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the United States and other Western participants charged that Russia was obstructing modifications in the Wassenaar control lists. See Emily Benson and Margot Putnam, “Export Controls and Intangible Goods,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, April 11, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/export-controls-and-intangible-goods.

16. According to U.S. administration officials, during the course of the administration of President Donald Trump from 2017 to 2021, India’s interest in obtaining near-term NSG admission receded. During President Joe Biden’s administration, India has not strongly urged the United States to reprioritize India’s candidacy.

Mark Hibbs is a senior nonresident fellow in the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.