2025 "Arms Control Person(s) of the Year" Winners Announced

For immediate release: January 14, 2026

Contact: Libby Flatoff, Policy and Program Associate, 202-463-8270 x104

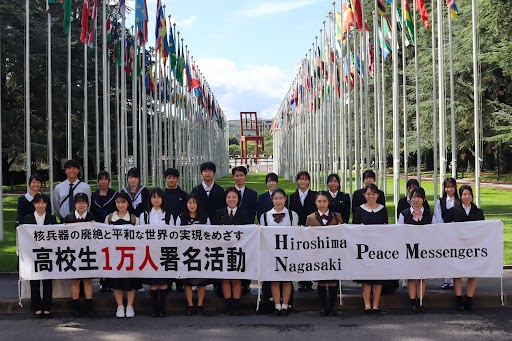

(Washington, D.C) -- A group of twenty-four Japanese high school students serving as "peace messengers" for the elimination of nuclear weapons were selected as the winners of the 2025 Arms Control Person(s) of the Year contest through a recent online voting process that engaged thousands of participants from more than 63 countries.

The students were nominated for their advocacy against nuclear weapons and their delivery of 110,000 signatures for world peace to the United Nations.

Ami Nagato, a 16-year-old student at Fukuyama Akenohoshi Girls' Senior High School in Hiroshima Prefecture, handed the signatures to U.N. officials on behalf of her cohort.

"I want people to know the devastation from the nuclear attacks and tell them about the importance of peace," Nagato told The Japan Times in September.

Since the student peace messenger program started in 1998, more than 2.83 million signatures have been collected. This year's student peace messengers were chosen from 18 prefectures in Japan.

“Looking at the recent state of world affairs, we feel that the threat of nuclear weapons is not diminishing, but rather intensifying,” the students told the Arms Control Association after being notified of their win.

“However, precisely because of these challenging times, we must stand on the principle of humanism: that nuclear weapons do not distinguish borders and will endanger countless citizens. Individually, our impact as high school students may seem limited, and sometimes we feel helpless. Yet, we have continued our work believing in our motto: “Our impact may be small, but we are not powerless,” they emphasized.

Their advocacy for peace and disarmament last year coincided with the 80th anniversary of the devastating U.S. atomic bombings of the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. By the end of 1945, an estimated 140,000 were killed by the blast, heat, and radiation effects of the nuclear attacks. As of August 2025, the registers of both atomic bombings’ victims exceed 540,000, including those who died after suffering from the long-term effects of radiation, according to the ICRC.

"As the number of hibakusha, or nuclear bomb survivors, dwindles over time, the leadership of young activists in recalling the catastrophic humanitarian impacts of nuclear weapons and pressing for disarmament becomes more important," said Daryl G. Kimball, Executive Director of the Arms Control Association.

“To ensure that the lasting suffering experienced by the Hibakusha is never repeated, we will continue to unite with our peers. Finally, we would like to express our deepest gratitude to everyone who has warmly supported us, and to my fellow Peace Messengers who have walked this path with us. Thank you very much,” the students concluded in their statement.

“Grassroots engagement and activism of young people -- in Japan and elsewhere around the world -- elevates awareness of the catastrophic risks posed by nuclear weapons, encourages progress for peaceful solutions, and is critical to advancing global efforts for disarmament and international security,” said ACA's Policy and Program Associate, Libby Flatoff.

ACA’s staff and Board of Directors nominated eight individuals and institutions for the honor of ACPOY 2025. Each of the nominees helped to advance disarmament, nuclear security, and international peace in unique and important ways.

This year’s second runner-up is the UN Delegation of Mexico and 5 other co-sponsoring states. The delegation successfully introduced and won approval for the first-ever United Nations First Committee resolution A/C.1/80L/L.56 on “possible risks of integration of artificial intelligence into command, control and communication systems of nuclear weapons.”

Close behind in the voting, which was open from Dec. 12, 2025, until Jan. 12, 2026, were the group of Catholic Cardinals and Bishops from Japan, South Korea, and the United States who were nominated for their pilgrimage to Hiroshima and Nagasaki on the occasion of the 80th anniversary of the U.S. atomic bombings, where they challenged the morality of nuclear deterrence and called for renewed action on disarmament.

The full list of 2025 nominees is available at ArmsControl.org/ACPOY/2025.

Previous recent winners of the “Arms Control Person of the Year” include Austrian Foreign Minister Alexander Schallenberg and the Austrian Foreign Ministry (2024), the U.S. Army’s Pueblo Chemical Depot in Colorado and the Blue Grass Army Depot in Kentucky (2023); the Energoatom staff working at Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant (2022) and Foreign Minister Marcelo Ebrard and the Government of Mexico (2021).

A complete list of winners from previous years is available here.