"[Arms Control Today] has become indispensable! I think it is the combination of the critical period we are in and the quality of the product. I found myself reading the May issue from cover to cover."

U.S. President Donald Trump said he told Iran’s supreme leader, “I hope you’re going

to negotiate…”

April 2025

By Kelsey Davenport

U.S. President Donald Trump sent a letter to Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, expressing interest in a nuclear deal, but the overture comes amid Iranian steps to expand its nuclear program and U.S. threats to strike Iran.

The contents of the letter—which was delivered to Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi by an Emirati official on March 12—have not been made public. Trump, however, told Fox News in an interview March 7 that the letter says, “I hope you’re going to negotiate because if we have to go in militarily it’s going to be a terrible thing.”

The day the letter was delivered, Khamenei said Iran is not interested in talks with a “bullying government” and described the missive as an attempt to “deceive global public opinion.” He said the U.S. threat of military action is “irrational” and warned that Iran is capable of “delivering a reciprocal blow.”

Despite Khamenei’s skepticism that the Trump administration is serious about an agreement, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian responded to the letter. In a March 30 speech, he said that Iran “rejected” the possibility of direct talks in its response but emphasized that the “path for indirect negotiations remains open.”

Trump has not articulated his aim for an agreement, but National Security Advisor Michael Waltz suggested that the United States will press for Iran to dismantle its entire nuclear program.

In a March 16 interview with ABC News, Waltz said Iran can either “give up” its nuclear program, including its uranium enrichment activities, “in a way that is verifiable” or “face a whole series of other consequences.” He made a similar comment in February, saying that the United States will talk to Iran only if they want to “give up their entire program.”

Iran’s mission to the UN tweeted on X that Iran would consider negotiations if the objective would be to “address concerns vis-à-vis potential militarization” of the country’s nuclear program but that talks “will never take place” if the goal is to discuss dismantlement.

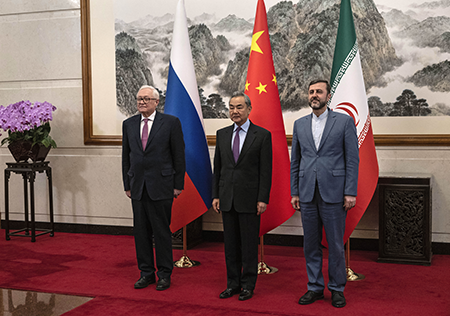

Iranian officials met their Chinese and Russian counterparts in Beijing March 14 to discuss the nuclear issue. In a joint statement released after the meeting, the three countries called for the termination of “all unlawful unilateral sanctions” and called for dialogue based on “mutual respect.” The statement said all parties should refrain from “any action” that escalates the situation. The trilateral meeting came after Russian President Vladimir Putin’s offer to mediate between Iran and the United States, but it is not clear if the two sides will accept Moscow as an intermediary.

Heightened regional tensions could affect Iran’s willingness to engage the Trump administration. Trump said he will hold Iran “fully accountable” for any further action by Houthi militants that threatens shipping lanes and U.S. interests. Trump made the statement on Truth Social after large-scale U.S. airstrikes began targeting Houthi-controlled areas of Yemen March 15. The Houthis increased military activities in the region after Israel announced it would block aid to Gaza.

Although Iran has provided military support and backing for the Houthi forces, it is not clear how much influence Tehran has on their actions. Trump, however, said the Houthi attacks “all emanate from, and are created by, IRAN.”

Trump’s direct outreach to Iran followed a quarterly report from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) that noted a significant increase in Iran’s stockpile of uranium enriched to 60 percent uranium-235, a level close to the 90 percent U-235 that is considered weapons grade.

The Feb. 26 report said Iran produced 91 kilograms of uranium enriched to 60 percent U-235 over the quarter, bringing the total stockpile of 60 percent U-235 material to 275 kilograms. Over the previous quarter, Iran had only produced about 18 kilograms of uranium enriched to 60 percent U-235. The significant increase in the stockpile was expected after Iran notified the agency of its intention to increase production of 60 percent U-235 material at its Fordow enrichment facility in December.

In a March 4 joint statement to the IAEA Board of Governors, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom called the increase in 60 percent U-235 material “alarming.” They said that “Iran has chosen to escalate its nuclear program … beyond any credible civilian use, thereby causing a proliferation crisis” and reiterated their commitment to a diplomatic solution.

IAEA Director-General Rafael Mariano Grossi called for diplomacy with Iran in a March 3 press conference. He said that “high-level engagement is indispensable.” He also called for concrete results on the IAEA’s yearslong investigation into undeclared Iranian nuclear activities from the pre-2003 period, saying it is time to “stop talking about process and start getting some answers.”

France, Germany, the UK, and the United States expressed similar concerns about the outstanding safeguards investigation in a March 5 statement to the board. The four countries said that “Iran must fully cooperate” with the IAEA or “the board must be prepared to find Iran in noncompliance” with its safeguards agreement.

Syria’s interim foreign minister also told the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons that the Assad regime’s chemical weapons program was “one of the darkest chapters” in world history.

April 2025

By Mina Rozei

Syria’s interim foreign minister called the Assad regime’s chemical weapons program “one of the darkest chapters” in world history and promised that the new government in Damascus will work to dismantle what is left, adhere to international norms, and ensure accountability for past wrongs.

Interim Foreign Minister Asaad al-Shibani made the commitments during a March 5 address to the Executive Council of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) in The Hague.

It was the latest step in an international effort to reset relations with Syria after the ouster of President Bashar al-Assad in December and a civil war in which his regime used chemical weapons against domestic opponents and thwarted OPCW attempts to hold Syria to account.

“The new Syrian government … is determined to rebuild Syria’s future on a foundation of transparency, justice and cooperation with the international community,” Shibani said.

He said that although the Assad era chemical weapons program “is not our program .… our commitment is to dismantle whatever may be left from it, to put an end to this painful legacy, and ensure Syria becomes a nation aligned with international norms.”

However, Shibani said achieving that goal will be challenging because the program was top secret and many involved officials have fled, likely taking key documents with them. He also cited complications from Israel’s decision to conduct airstrikes in Syria after the regime fell.

“We lack the information, expertise, technical capacity, and human resources to fully assess and address any chemical weapons that may still exist,” he said.

Shibani addressed the executive council meeting after OPCW Director-General Fernando Arias held talks with interim president Ahmed al-Sharaa in Damascus in February. The OPCW presented a nine-point plan of action to assist with locating and destroying the remaining chemical weapons stockpile.

Shibani said the Syrian government began acting on the plan after the visit and identified a Foreign Ministry official to liaise with the OPCW on chemical weapons issues. The liaison already has met with the OPCW and Syria is working with the OPCW Technical Secretariat to plan further operational trips to Damascus in the near future, Shibani said. He credited the OPCW and its member states for documenting the chemical attacks perpetrated in Syria.

The foreign minister asked OPCW member states and the broader international community to provide information, coordination, technical assistance, capacity building, and other resources on the ground in Damascus and in The Hague. He also called for lifting economic sanctions on Syria to allow the OPCW to operate on the ground, stem the spread of criminal networks, and allow the war-torn country to recover economically.

Several OPCW member states supported Shibani’s appeal, stressing the “historic” opportunity to strengthen the norm against chemical weapons that the organization is now facing.

A top North Korean official threatened to escalate Pyongyong’s nuclear program after a U.S. aircraft carrier

visited South Korea.

April 2025

By Kelsey Davenport

North Korea threatened to escalate its nuclear weapons program after the United States announced it was sending an aircraft carrier to South Korea for combined, joint military exercises.

The USS Carl Vinson docked in Busan, South Korea, ahead of the annual combined, joint Freedom Shield military exercise, held March 10-20. The South Korean navy described the carrier’s participation as a demonstration of the “permanent and ironclad” U.S. extended deterrence commitment to South Korea.

Kim Yo Jong, sister of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, called the U.S. decision to send the USS Carl Vinson to South Korea a “provocative” act that shows the “most hostile and confrontational will” toward North Korea.

Kim Yo Jong, who serves as the vice department director of the Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea, said in a March 4 statement to the state-run Korean Central News Agency (KCNA), that U.S. actions offer “sufficient justification [for Pyongyang] to indefinitely bolster up its nuclear war deterrent.” North Korea also will examine its options to threaten “the enemy at the strategic level” and set new records to demonstrate North Korea’s strategic deterrence capabilities, she said.

Kim did not specify what capabilities North Korea may seek to demonstrate or what steps the country may take to enhance its nuclear weapons program. North Korea launched several ballistic missiles before and during the South Korea-U.S. exercise, but the systems did not appear to demonstrate any new capabilities.

South Korea said the March 10 launch likely involved combat-range ballistic missiles that fly very short distances. Before the exercise, North Korea launched a strategic cruise missile. A Feb. 28 KCNA report on the launch said the activities were carried out to inform adversaries about North Korea’s retaliatory capabilities and its nuclear readiness.

After the Freedom Shield exercise commenced, North Korea accused South Korea and the United States of warmongering in a March 11 KCNA statement. The day before, North Korea said the yearly exercise was aimed at practicing a preemptive attack on North Korea’s nuclear facilities. The statement reiterated that North Korea views U.S. hostile actions as a justification for the “radical” growth of its nuclear arsenal.

The combined, joint exercise included more drills than last year but did not include live-fire drills. South Korea and the United States described Freedom Shield as defensive drills aimed at countering a range of North Korean threats emanating from land, sea, space, and cyber domains.

Russia also criticized the combined, joint exercise and said North Korea’s decision to expand its own deterrence capabilities in response is justified. Maria Zakharova, the spokeswoman for the Russian Foreign Ministry, said that Freedom Shield “could trigger a new round of escalation.” She condemned the United States for “saber-rattling” and said there are avenues for peacefully resolving tensions on the Korean peninsula. She encouraged U.S. President Donald Trump to reach out to Kim and suggest “practical steps” to stabilize the situation.

The Trump administration has called for the denuclearization of North Korea and reiterated its support for South Korea, but it is not clear if Trump will try to use his personal relationship with Kim to engage North Korea diplomatically—or if Kim wants to negotiate with the United States.

North Korea appears to be investing in the fissile material production capabilities necessary to expand its nuclear deterrent. International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Director-General Rafael Mariano Grossi raised concerns about North Korea’s fissile material activities March 3. He said there are “strong indicators” that North Korea is preparing for a reprocessing campaign, which removes weapons-grade plutonium from the spent nuclear fuel. Grossi said it appeared that the 5-megawatt reactor at the Yongbyon nuclear complex resumed operations in October 2024, likely after being refueled.

Grossi also described Kim Jong Un’s recent call for expanding weapons-grade nuclear material production a “serious concern.”

In addition to plans to expand its nuclear arsenal, North Korea announced March 8 that it is building its first “nuclear-powered strategic guided missile submarine” and showed pictures of Kim Jong Un inspecting what appeared to be a submarine under construction. It was not clear from the photos how close the submarine is to completion.

North Korea has conventionally powered submarines, but the diesel engines powering those systems are noisy, making the submarines easier to track. North Korea also has tested submarine-launched ballistic missiles capable of delivering a nuclear warhead, but its existing fleet of submarines probably could not carry those missiles.

On his shipyard visit, Kim said North Korea is modernizing its underwater forces to counter the “gunboat diplomacy of the hostile forces,” according to KCNA.

States-parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons recommitted to implement and universalize

the pact.

April 2025

By Shizuka Kuramitsu

States-parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) concluded their third meeting by renewing a commitment to effectively implement and universalize the pact amid escalating nuclear tensions.

Voicing growing concerns over global instability, the states-parties adopted a political outcome document that reaffirms the roles played by “the majority of non-nuclear-armed States … in bridging divides, promoting diplomacy, and reinforcing multilateralism.” They also recommitted “to unite and mobilize the international community around the imperative and urgency of progress toward eliminating the existential threat posed by nuclear weapons.”

The meeting was held March 3-7 in New York.

The treaty, which goes beyond other arms control agreements by banning nuclear weapons, entered into force Jan. 22, 2021, and has been ratified by 73 states. But its effectiveness is hampered by the fact that none of the states possessing nuclear weapons—China, France, India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States—have signed on.

The states-parties agreed that alarming international developments highlight the imperative of disarmament and nonproliferation initiatives. “Heightened geopolitical tensions, further expansion and modernization of nuclear arsenals, the increasing salience of nuclear weapons in military and security doctrines, including through security guarantees, and the growing dangers of nuclear proliferation and potentially devastating nuclear arms races demand immediate and decisive action from the international community,” the political outcome document stated.

At the opening session March 3, Izumi Nakamitsu, the UN high representative for disarmament affairs, said that “sadly, these trends have continued and only intensified. Geopolitical tensions remain unresolved, and are also dramatically evolving…. Yet, even in this challenging moment, there are reasons for hope, especially in relation to the full implementation of the TPNW.”

Ahead of the meeting, the officials who had been working on the intersessional initiative facilitated by Austria at the direction of the previous meeting of states-parties produced their report. (See ACT, January/February 2024.) It outlines a comprehensive assessment of how nuclear weapons pose security threats to the TPNW states and recommendations on how they can challenge the nuclear deterrence doctrines of nuclear-armed states.

In citing the report, the outcome document said that “nuclear deterrence is posited on the very existence of nuclear risk, which threatens the survival of all.” It added that the states-parties showed their commitment to expand efforts to continue challenging nuclear deterrence and aiming for a paradigm shift in nuclear doctrines.

On the TPNW mandate of establishing an international trust fund for victim assistance and environmental remediation from the consequences of nuclear use and testing, the meeting decided to produce a report no later than the end of July 2026.

The meeting occurred as states that are not TPNW members are intensifying reliance on nuclear deterrence in their security doctrines. On March 5, French President Emmanuel Macron said his government would be open to discussing nuclear extended deterrence with its European partners against the backdrop of possible shifts in U.S. security guarantees to NATO allies, as mooted by the Trump administration.

NATO members Belgium, Germany, and Norway observed the past two TPNW meetings but skipped this one. Albania was the only NATO member to attend, but left after the first day. According to a March 14 report in the Chugoku Shimbun, Hiroshima’s local newspaper, a NATO diplomat explained that NATO members, after consultations, decided to skip the meeting.

Japan also was absent, despite strong domestic pressure to attend the meeting for the first time as an observer after the 2024 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Nihon Hidankyo, the lobby group for World War II atomic bomb survivors known hibakusha. (See ACT, December 2024.)

Concluding the meeting, Akan Rakhmetullin of Kazakhstan, the meeting president, called the event a success. “The risks associated with [nuclear weapons] continued existence are greater than ever,” he said. “Our discussion this week reinforced the urgency of concrete steps towards a global disarmament.”

Fifty-five states-parties, 31 observer states, and 163 nongovernmental organizations participated in the weeklong TPNW meeting. South Africa was elected chair of the first TPNW review conference, set for November 2026.

Harold Agyeman of Ghana, Akan Rakhmetullin of Kazakhstan and Jarmo Viinanen of Finland, current and past chairs of the preparatory committees for the 2026 nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty Review Conference respectively, are bullish on the 1970 pact but stress the need for constructive action at this month’s PrepCom.

April 2025

Since coming into force a half-century ago, the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) has been the central pillar of the international arms control regime and specifically, efforts to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons. Its 191 member states are divided into two groups—the five nuclear-weapons states known as the P5 (China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States) and all the rest, who pledged never to acquire such weapons. The latter group has been promised access to peaceful uses of nuclear energy (such as power and medical uses) in return for forsaking nuclear weapons; the nuclear-weapon states have committed to pursue complete disarmament. The non-nuclear weapon states have not gotten the peaceful energy benefits they expected, and disarmament has halted. Meanwhile, the NPT has become increasingly embattled as the full-scale Russian war on Ukraine has exacerbated geopolitical tensions, other treaties collapsed, Iran and North Korea keep advancing their nuclear programs, and several other states threaten to start their own programs. It is a difficult environment ahead of the 2026 NPT Review Conference when member states will take stock of the treaty and attempt to shore it up and nudge it forward. Recent conferences have failed to agree on consensus outcome documents. The last of three meetings to prepare for the 2026 event will be April 25-May 9. To explore what the 2026 Review Conference could achieve and how this year’s preparatory committee (PrepCom) meeting could be useful, Carol Giacomo, chief editor of Arms Control Today, and Shizuka Kuramitsu, a researcher with the Arms Control Association, interviewed Ambassador Harold Agyeman of Ghana, the chair of this year’s PrepCom meeting; Deputy Foreign Minister Akan Rakhmetullin of Kazakhstan, the 2024 chair; and Ambassador Jarmo Viinanen of Finland, the 2023 chair. This transcript has been edited for space and clarity.

Arms Control Today: The nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty is more than 50 years old. Is it still fit for the purpose for which it was created, or is it too battered?

Ambassador Harold Agyeman: There’s no doubt that the world is in a very difficult place. There are a lot of uncertainties across different parts of the world, and it portends very severe risks for all of us, especially when you take into account that the driving force relates to some of the P5 states. Nonetheless, I think that the NPT has stood its ground as a stabilizer in avoiding proliferation for all these decades. It has held back the proliferation rates that, at the time it was negotiated, the threat was very real. I think the fact that it’s held as a stabilizing force in avoiding proliferation is a major achievement.

Certainly, the NPT is under pressure because the aspirations that many of our states-parties held—especially at the time of the review and extension conference in 1995, that there would be a stronger commitment to disarmament—has not necessarily panned out. That is something that we need to look at and find a resolution for. Also, the issues relating to the inalienable rights of non-nuclear-weapon states, especially for the peaceful use of nuclear energy and other applications, needs to be stepped up because this is the other end of the bargain that many have committed to.

The NPT is indeed fit for purpose, and if we were to negotiate it today, it would be very difficult to have such an agreement. We need to make very good use of the NPT to ensure that the arrangement that it was intended to provide in terms of disarmament of our nuclear weapons, the nonproliferation regime, and the peaceful use of nuclear energy, are reinforced and implemented accordingly.

Ambassador Jarmo Viinanen: The treaty is still fit for purpose. There are a lot of pressures on the treaty, from outside the treaty’s realm, but also from the inside. Yet, we have to remember that the treaty is functioning well every day. We have for example the IAEA [International Atomic Energy Agency] safeguards in place, which actually curb proliferation risks all the time, every day, everywhere. We have a very elaborate system for promoting the peaceful uses of nuclear energy for development to combat climate change, and so on. We certainly need to do better in that respect.

Another issue concerning nuclear disarmament: This is the only treaty where the recognized nuclear-weapon states have agreed to a legal obligation to engage in good faith in nuclear disarmament. Without that, there wouldn’t be a legal commitment or obligation from their side. At the same time, when we are approaching the review conference next year, we can see that the turmoil that we are facing in today’s world actually makes all the purposes of the treaty even more urgent and important. It is clear that in this very difficult situation, we need more nuclear disarmament than ever before. It has become obvious with the Russian war in Ukraine and with the nuclear threats that have followed throughout the war.

It means that something concrete has to happen in this respect. It’s not going to be enough that the nuclear-weapon states say that the international environment is not conducive to nuclear disarmament. They are the states-parties that have the most leverage, they are permanent members in the UN Security Council. They can do better and they must do better. At the same time, concerning proliferation, we can see even during the last two to three weeks in multiple places where there is serious discussion about acquiring nuclear weapons, in states-parties that never had nuclear weapons before but now are contemplating seriously whether they should take that path. This should be a wake-up call for all of us to do everything to curb the tendencies that lead to nuclear proliferation because we don’t need any more states with nuclear weapons in this world.

The third issue is on the peaceful uses side. As with proliferation and nuclear disarmament, we can see that climate change is advancing at a very rapid pace. We see serious catastrophes happening in different parts of the world, and they are partly due to climate change. Nuclear energy, used in a peaceful manner, can actually be helpful in combatting climate change and advancing development, so we need to do better in that respect.

Deputy Foreign Minister Akan Rakhmetullin: The NPT is the only legal instrument where officially recognized nuclear powers have taken responsibilities to move forward the issues of disarmament and nonproliferation. Of course, the treaty is burdened by the overall political context—be it Ukraine, overall global developments, lack of mutual trust. If I may compare it with my recent presidency over the third meeting of states-parties to the TPNW [Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons] in New York, the TPNW is comprised of like-minded countries, non-nuclear-weapon states, that are united and they discuss different issues, like universalization, the impact on affected communities, on individuals, on the environment.

In the context of the NPT, it is very optimistic for us that the nuclear powers remain NPT states-parties, and not one of them has said the treaty is no longer relevant—that it is not fit for purpose and that we have to abandon it and go somewhere else. They are present in the NPT and they speak. They don’t agree with each other all the time, but they talk, and they do listen to each other. In some instances, they agree; in some they do not. But this treaty is the only treaty which remains relevant in terms of the global nonproliferation regime.

There are seminal issues within the treaty which are most controversial. The pillar on peaceful uses of nuclear energy remains least controversial and where we can think about areas that unite [and] converge the vision of the different states-parties, including nuclear and non-nuclear-weapon states. We also very much rely on the authority and the talking ability of non-nuclear actors to somehow try to influence the nuclear powers. What I brought away from chairing the second NPT PrepCom last year in Geneva is that we still have some domains where it is really very difficult for countries to converge their positions. Countries all agree on the relevance and the importance of each component of the treaty, but they have their own vision of how this or that component should be implemented.

I think at the 2026 Review Conference we have to at least reconfirm our commitments, which we attained during the previous review conferences. Given the political context [and] geopolitical developments, it is really very hard to build trust.… But again, just to confirm what my colleagues said, this treaty is relevant, and it is fit for purpose.

ACT: What should NPT states-parties do to achieve success at the 2026 NPT Review Conference? What specific steps must states-parties undertake to fulfill their NPT obligations and improve the atmosphere?

Rakhmetullin: It’s really a million-dollar question, and it’s really hard to answer that because they all come to the review conference or the PrepCom with their prepared national positions and national statements. We always think we’re being strong proponents of multilateralism but all these negotiations are a two-way avenue, because if we want to take something, we have to give something. I think during the preparatory period to the review conference, it is good to know each country’s redlines. They’re actually well known, and I don’t think they will shift away from their redlines. But we hope they can demonstrate a certain degree of flexibility in order to attain some tangible progress.

We can just reconfirm the existing commitments within the review conferences of 1995, 2000, and the latest, 2010, because having no result in the conference is also a result on its own because countries at least sat together, they have discussed complex issues, they again indicated their concerns, their priorities. [Although some alternative approaches were initially considered ahead of the 2024 PrepCom] we decided just to go with the existing practice, and to understand what each country is ready to take and what it’s not. Unfortunately, countries were not flexible enough and we could not arrive at a consensus, but we managed to at least produce a factual summary which served as a more procedural outcome. We just managed—sometimes by playing with different language, like adding a footnote to the document—to bring it to a situation where the countries did not oppose having some kind of final document. My strong conviction is that states-parties have to produce some kind of reflections [from the preparatory committees], because having nothing from the deliberations is just the way to nowhere.

Viinanen: The questions are very complicated. What everybody can do is adhere to what has been agreed earlier within the NPT. If we all would live up to the standards which are laid out, for example, in the UN Charter, the world would be a much better place and it would be much easier to agree on these things. But I think it’s very important that there’s a strong commitment in every state-party that we need to get an outcome from the review conference

next year.

We have had two review cycles without any outcome, and although that’s not the measurement of the success of the treaty or whether the treaty is fit for purpose, if we have this kind of diplomatic exercise—three PrepComs, a Review Conference of four weeks—that’s a lot of effort, it’s a lot of time, it’s a lot of money. We need to come out with an outcome because if we are not trying to succeed in that, it might be detrimental for the credibility of the treaty. So, this is the main issue. And as Akan said, when we come together, everybody has to compromise on certain things; otherwise, it’s not going to happen.

Another issue is political leadership. Some of our colleagues have been dealing for a very long time with these issues, and they know every detail in the whole process. Sometimes we need to have a little bit more political engagement in our capitals, because sometimes it would be a little bit easier for political leaders to overcome the challenges which sometimes are overwhelming for us diplomats to do. So, I would like to see the capital involvement on a political level.

As for possible outcomes, we cannot achieve miracles, but of course there has to be a recommitment, stronger language concerning the need to address nuclear disarmament. Here I would once again challenge our friends and colleagues in the nuclear-weapon states: Listen to the concerns of the other countries which are not in possession of nuclear weapons. Listen to the concerns which came from the TPNW meeting. Even though you don’t agree on the substance, you have to see that the concern of the majority of the states-parties to the TPNW is a real one, and it has to be addressed.

The same applies to nuclear proliferation. I don’t think that nuclear proliferation would be in any state-party’s interest. We have to be clear on this. We don’t need to have all countries possessing nuclear weapons. It would be detrimental for everybody.

Agyeman: I think that the expectation is that we should have an outcome [document] and the process for the NPT review cycle is such that it requires consensus. It will require all of us to give and take and to show flexibility during the negotiation of the final outcome document in 2026. This is a difficult task, but it’s important that we do so for some of the reasons that we have mentioned. Indeed, as a chair, it is not my intention that our ambition should exceed that of the states-parties. At the same time, I’m very conscious of the fact that there’s a strong expectation from many people around the world to have a pathway ultimately set out toward denuclearization and disarmament of nuclear-weapon states. We cannot afford to have a RevCon [Review Conference] that does not come out with an outcome document. I think that flexibility is therefore required.

One issue that Ambassador Viinanen spoke about relates to the engagement of the nuclear-weapon states themselves, because it’s important that they also engage strongly…. I’m encouraged by some of the remarks that I’ve heard from the new leader of the United States in the direction of engagement. I think it’s important that that engagement takes place, and that trust be rebuilt, in ways that can ensure that there is a cooling down of the nuclear rhetoric. It could also help to ensure that the concerns that are coming up in terms of countries that are now beginning to think about acquiring nuclear weapons, in terms of the proliferation race, can be addressed.

At the same time, there is a strong pressure from many parts of the world, including from non-nuclear-weapon states, that there should be a recommitment to the existing obligations that advances the disarmament regime. The clarity that is required is to say that proliferation is prohibited and that clarity is needed to be expressed at the RevCon in 2026. The issues relating to the peaceful uses of nuclear energy need to be practicalized so that many non-nuclear-weapon states will see a benefit from being part of this treaty.

ACT: Ambassador Agyeman, can you be more specific about the encouraging things that you heard from U.S. President Donald Trump? Are you reacting to his public remarks or has he said something specific to you?

Agyeman: I’m referring to his general remarks, which for me is encouraging. As Ambassador Viinanen indicated, there is a need for high-level political leadership to ensure that the risk is brought down. And [Trump’s] indication of a willingness to be able to engage in that direction is one that I find encouraging. I hope that we can leverage that to engage in discussions, including on the suspension of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty by the Russian Federation, and look beyond 2026 in terms of what will be done by these two major nuclear-weapon states.

ACT: There have been several references today to concerns about other states possibly going nuclear. Other than Iran, what states are you talking about?

Viinanen: Iran is a very specific case. There have been long-term oversight issues with the Iranian nuclear program, dating back before 2000. It doesn’t look like Iran has made a decision to acquire a nuclear weapon. They want to keep it on a certain level. But it’s an issue which needs to be solved. And the key in solving the matter, the trust issue, is the Iranian government itself. It has to come to terms with the IAEA regulations, IAEA demands, and actually respond to them in a credible way so that we can put this issue aside.

The more current issues are related to changes in U.S. policy, which have raised the issue in some countries of whether they can rely on U.S. extended nuclear deterrence. This shows that extended deterrence, whether you like it or not, has been a very effective way of exercising nonproliferation. When there is extended deterrence, there’s no need for many countries to acquire nuclear weapons themselves.

The more current issues are related to changes in U.S. policy, which have raised the issue in some countries of whether they can rely on U.S. extended nuclear deterrence. This shows that extended deterrence, whether you like it or not, has been a very effective way of exercising nonproliferation. When there is extended deterrence, there’s no need for many countries to acquire nuclear weapons themselves.

We are a long way from changes in this respect. But even serious political talk about the matter in some countries already should be a concern enough that something needs to be done. And I hope this can be solved in a way that there’s not going to be countries under the umbrella of extended deterrence who see a need to change their policy. It depends on all of the countries in that alliance or those alliances and partnerships.

ACT: Does this concern relate to NATO and France’s talks with other Europeans about possibly extending its nuclear deterrence to them?

Viinanen: I mean all of these are ripples of the same political effect, the political turmoil which we are seeing. There are a little bit different origins for each of them, but it’s part of the same issue, concern about the reliability of the extended deterrence, the security framework which had been existing in Europe for more than 75 years. But the issue when it comes to NPT is the cascading effect. If there is going to be one other country acquiring nuclear weapons, it could be easily said that there would be a second one, a third one, a fourth one. Then, the proliferation is much more difficult to contain, and therefore, there shouldn’t be any more countries acquiring nuclear weapons.

Rakhmetullin: On one hand, it’s a matter of internal policy, of the sovereign right of any country that is eligible to ensure its security by different means. At the same time, we are a bit concerned with this rhetoric in general and that this proposal is not fully understood, particularly the underlying reasons behind it, why it happened, and why France proposed that. But at the same time—I’m talking from my personal capacity as the nation of Kazakhstan—we’re a bit concerned when countries go that far.… The NPT clearly speaks about five countries which are eligible to legally have the right to possess the nuclear weapon. Going beyond that undermines the letter and spirit of the treaty.

I had numerous meetings with our French colleagues, and we know that nuclear deterrence is part of their national security doctrine. At the same time, it shouldn’t be done at the expense of the existing fragile balance. I think a similar reaction would follow any kind of rhetoric from the other side, because we have already seen that different countries were not happy with this idea, including saber-rattling rhetoric and plans to deploy more nuclear weapons or to reconsider the nuclear sharing policy.

Agyeman: The question that you pose is not an easy one, and it relates to issues largely out of the NPT but impacting the NPT strongly. From my perspective, nuclear deterrence, nuclear sharing, nuclear umbrella—all these are being redefined. We need to be very careful about the manner we go in those directions and avoid a situation where we could escalate the nuclear rhetoric and lead to a new arms race.

There needs to be a frank and robust discussion among the P5 nuclear-weapon states and for clarity to be established that it will not be in their interest—nor in any of us outside of the P5 interest—if that situation is made to unbound itself and lose control of the situation in terms of the proliferation risk that my colleagues have talked about. That for me is a major concern, especially with the unfolding situation that we are witnessing—because once one has it, another will seek it. And there will be no end to the risk. Even for the five nuclear-weapon states that are recognized under the treaty, it is difficult to ensure synchrony of actions lately.

ACT: The Russian war on Ukraine has complicated international relations for several years. You all stress the need to make progress at this next NPT Review Conference. How will you mitigate the disruption that the war is causing?

Agyeman: The situation in Ukraine today is not at the same place it was in 2022. And so, we have a bit of room to work around in a way that Ukraine does not become a negative element in the efforts to achieve consensus. Issues relating to nuclear safety and security in terms of the Ukrainian civilian nuclear infrastructure continue to be of concern but there is a bit of engagement by the IAEA director-general and his team to ensure that that risk is largely mitigated. Also, when we take the efforts that the new U.S. administration is making for peace in Ukraine, I anticipate that if the trajectory that we see is sustained, then by 2026 it will not be the big concern that should impede common agreement. But these are of course things that one cannot have full control over, because it’s not yet been resolved.

Agyeman: The situation in Ukraine today is not at the same place it was in 2022. And so, we have a bit of room to work around in a way that Ukraine does not become a negative element in the efforts to achieve consensus. Issues relating to nuclear safety and security in terms of the Ukrainian civilian nuclear infrastructure continue to be of concern but there is a bit of engagement by the IAEA director-general and his team to ensure that that risk is largely mitigated. Also, when we take the efforts that the new U.S. administration is making for peace in Ukraine, I anticipate that if the trajectory that we see is sustained, then by 2026 it will not be the big concern that should impede common agreement. But these are of course things that one cannot have full control over, because it’s not yet been resolved.

Rakhmetullin: We are trying to be optimistic about the progress we make with this because we know that today, President Trump’s talks with the [Russian] president are ongoing. That gives us a hint of feeling that the bloodshed and the conflict may deescalate from its active phase. At the same time, I’m not sure that Russia will withdraw its presence from the Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant. I think the Ukrainians, after three-plus years of conflict, will also have so many wounds—moral, financial, military, emotional—that they will not let go easily. I think they will be using this opportunity during the 2025 PrepCom, being present in the same room with Russians and with other pro-Ukrainians stakeholders, to promote their own interest, which is opposing the interests of Russia. This may impede progress. In this case, we would need to appeal to the political wisdom of some other states, which have their own vision and have their good contacts with the Ukrainian colleagues and with Russians, to try to mitigate the overall conflict and the overall negative sentiment in the room.

Iran also keeps us quite optimistic that they’re not leaving the treaty. They are there, they are quite loud, they try to promote their own interests, their priorities are to protect them, try to find some kind of positive outcome. Maybe they are not as flexible as many countries want to see them be, but at the same time it gives us a feeling of optimism that they are at least engaged in the process, they are not leaving the room and they are trying to somehow contribute to the review process.

Viinanen: As Harold said, we are in a different situation with the Russian war in Ukraine than in the summer of 2022. Probably in the spring of 2026 we are going to be even in a more different situation. So, we don’t know how that is going to look like next year.

During the high-stakes, February 28 Oval Office meeting when U.S. President Donald Trump tried to bully Volodymyr Zelenskyy into accepting a pro-Kremlin formula for ending the war in Ukraine, he accused the Ukrainian president of not wanting peace, and claimed he was “gambling with the lives of millions of people. You’re gambling with World War III.”

April 2025

By Daryl G. Kimball

During the high-stakes, February 28 Oval Office meeting when U.S. President Donald Trump tried to bully Volodymyr Zelenskyy into accepting a pro-Kremlin formula for ending the war in Ukraine, he accused the Ukrainian president of not wanting peace, and claimed he was “gambling with the lives of millions of people. You’re gambling with World War III.”

Although it is reassuring that Trump wants to avoid nuclear war, his comments show a failure to comprehend who and what actually drives nuclear risk: the nuclear weapons and deterrence policies of the nuclear-armed states that are used to justify their possession.

In reality, Zelenskyy is leading a non-nuclear-weapon state that is defending itself from a brutal, unprovoked invasion by Russia, a larger nuclear-armed state that has violated its 1994 pledge (shared by the United States and the United Kingdom) to respect Ukraine’s territorial integrity and refrain from the use of military force against it.

Those assurances were extended to facilitate Ukraine’s decision to relinquish the strategic nuclear weapons it inherited from the Soviet Union and to join the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). Today, Zelenskyy is still seeking to ensure his country’s independence and a just peace, which requires security assurances that are meaningful and durable.

Trump’s Republican allies have become so fearful of his threats of political retribution that they fail to acknowledge, much less call out, his numerous exaggerations and lies. But when it comes to war and peace and nuclear weapons, there can be no excuses.

Trump and his acolytes should acknowledge that Russia continues to illegally occupy and attack Ukrainian territory, and it is Russian President Vladimir Putin who has threatened World War III. Not long after launching the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Putin made veiled threats of nuclear weapons use if any state were to interfere. “No matter who tries to stand in our way ... they must know that Russia will respond immediately, and the consequences will be such as you have never seen in your entire history,” Putin said.

Seven months later, as Russian forces were in retreat in eastern Ukraine, Putin suggested that he might order the use of shorter-range nuclear weapons “if the territorial integrity of our country is threatened,” including the territory in Ukraine that Russia had illegally seized. “This is not a bluff,” he added.

Of course, the Soviet Union and the United States issued various kinds of nuclear threats and alerts during the Cold War, before the 1962 Cuban missile crisis and after. However, Russia’s recent nuclear rhetoric, which was designed to shield its assault against a non-nuclear-weapon state, is unprecedented and unacceptable in the post-Cold War era.

During his presidency, Joe Biden did not reciprocate Putin’s threats of nuclear annihilation. Instead, he reaffirmed that U.S. and NATO forces would not become engaged directly in the war, warned that the use of nuclear weapons would lead to nuclear escalation, and ensured the supply of weapons and intelligence to help Ukraine thwart aggression.

Trump may find it hard to adopt such a balanced approach. In August 2017, he engaged in a dangerous round of tit-for-tat taunts with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, threatening North Korea with nuclear “fire and fury like the world has never seen.”

Nevertheless, rather than chastise Zelenskyy, it will be in the U.S. and global interests for Trump to stand up to Putin and say that any further nuclear threats would be “inadmissible,” as the Group of 20 countries declared in 2022.

During Trump’s discussions with Putin, he should also note that nuclear threats clearly violate the 1973 Agreement on the Prevention of Nuclear War, which commits Russia and the United States to “refrain from the threat or use of force against the other Party, against the allies of the other Party and against other countries, in circumstances which may endanger international peace and security.” Such an agreement should be extended to include China, France, and the United Kingdom.

Trump and the leaders of the world’s other eight nuclear-armed states must recognize that for non-nuclear-weapon states such as Ukraine, nuclear weapons and the deterrence strategies of the nuclear-armed states represent a grave threat to their security.

As explained in a new report issued by states-parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, “the nuclear policies of all nuclear-armed states are based on implicit or explicit nuclear threats, which create an aggregated and interconnected set of global and existential risks that undermine the security of states not engaged in this practice. From this perspective, the theory of nuclear deterrence is a highly precarious gamble: one that no human being or Government should be entrusted to make.”

Trump, Putin, and the other leaders of the nuclear-armed states are gambling with the lives of every person on the planet. To improve humanity's odds of survival, we must demand that they follow through on their obligation under Article VI of the 1968 NPT to engage in good-faith negotiations to reduce the role and number of nuclear weapons and to achieve nuclear disarmament.

In recommending withdrawal, defense ministers said their military forces needed more flexibility to respond to increased threats from Russia and Belarus.

April 2025

By Xiaodon Liang

The defense ministers of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland announced March 18 that they would recommend withdrawal from the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty to their respective governments.

In a joint statement, the ministers said that “threats to NATO member states bordering Russia and Belarus have significantly increased” and withdrawal would “provide our defence forces flexibility and freedom of choice to potentially use new weapons systems and solutions to bolster the defence of the alliance’s vulnerable Eastern Flank.”

Nevertheless, the four countries will “remain committed to international humanitarian law, including the protection of civilians during armed conflict,” the ministers said.

Latvian Prime Minister Evika Silina confirmed March 18 that her government has “decided to initiate the process to withdraw” from the treaty, according to Latvian Public Media.

Tamar Gabelnick, director of the International Campaign to Ban Landmines, strongly condemned Latvia’s move in a March 19 press release and questioned how the country would “uphold its obligations towards International Humanitarian Law by reintroducing a weapon that is unable to distinguish between civilian and military targets.”

Finland is also considering withdrawing from the treaty, Defense Minister Antti Hakkanen, told Reuters Dec. 18.

The Mine Ban Treaty, which is limited in scope to antipersonnel mines, prohibits their use, development, production, stockpiling, and transfer. The treaty entered into force in 1999 and has 165 states-parties.

The decision comes three years after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and follows recent suggestions by the United States that it might condition its collective defense commitments under the NATO alliance.

Speaking before the Polish parliament March 7, Prime Minister Donald Tusk said that Poland also was considering withdrawal from the 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions.

Although the Mine Ban Treaty permits withdrawals, countries must give six months’ notice and cannot be involved in ongoing armed conflict. Russia has used landmines extensively across Ukrainian territory, according to the landmine campaign’s Landmine Monitor 2024 report. In 2022, Human Rights Watch accused Ukraine of deploying mines by rocket.

Neither Russia nor the United States are states-parties to the Mine Ban Treaty, but Ukraine is. At the November 2024 review conference of the treaty’s states-parties, Ukraine reiterated its commitment to destroying its Soviet-era stockpile of landmines, of which some 4.3 million remain. In the same month, it received a first transfer of landmines from the United States. (See ACT, December 2024.)

An agency report said an investigation revealed evidence that the CS riot control agent was used on battlefield but did not identify who was responsible.

April 2025

By Mina Rozei

The Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) has found more evidence of chemical weapons use in Ukraine, it said in a Feb. 14 report.

The findings came after Ukraine requested that the OPCW investigate three separate incidents in October 2024 when toxic chemicals were allegedly used along the confrontation lines between Russian and Ukrainian forces in the Dnipropetrovsk region.

The OPCW deployed its technical assistance visit team on two missions to Ukraine to collect documents, digital files, witness testimonies, and environmental samples. These samples were analyzed independently by laboratories that are part of the OPCW network, and the organization confirmed that the chain of custody was maintained throughout the analysis process.

The laboratory analyses revealed the presence of 2-Chlorobenzylidenemalononitrile (CS), in all three alleged instances. CS is a riot control agent, which when used in a conflict setting constitutes a violation of the Chemical Weapons Convention. OPCW Director-General Fernando Arias said the CS was used in riot-control-agent grenades.

The report did not identify who was responsible for using CS on the battlefield. The OPCW Technical Secretariat circulated a note at the most recent Executive Council meeting stating that “the mandate of the secretariat under this [technical assistance visit] request was never to look at where the grenades came from but to determine whether they were indeed found along the frontlines.”

This is not the first time that CS has been found on the battlefield in Ukraine. The OPCW confirmed the presence of the CS agent in November after its first technical assistance visit to Ukraine in July. (See ACT, December 2024.)

The findings were published several weeks before the most recent meeting of the OPCW Executive Council. At the meeting, held March 4-7 in The Hague, the Russian delegation circulated a diplomatic note criticizing the report for containing “discrepancies” and casting doubt on the integrity of the chain of custody. The delegation also circulated a document Feb. 28, before the council meeting, in which it accused Ukraine of using toxic chemicals as weapons against Russian military and civilians.

The Ukrainian delegation exercised its right of reply at the council meeting by issuing a statement in which it rejected the Russian allegations as “disinformation,” and said Russia “continues to use riot control agents against Ukrainian troops.” At the meeting, the OPCW Technical Secretariat responded to Russia’s accusations by saying that “the secretariat works impartially for the 193 states-parties to the convention, including the Russian Federation.”

A continuing resolution to fund the federal government through Sept. 30 will shift $185 million from the nonproliferation programs to weapons activities.

April 2025

By Xiaodon Liang

The U.S. Congress approved a $185 million cut to the defense nuclear nonproliferation budget managed by the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) in a March 14 continuing resolution that funds the federal government through Sept. 30, the end of the 2025 fiscal year.

The resolution transfers those funds instead to the NNSA’s weapons activities budget, bringing it up to $19.29 billion for the remainder of this fiscal cycle.

The slashed nonproliferation funding is equal to a 7.2 percent cut. According to an analysis by the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation, the reduction will probably impact NNSA programs on nuclear smuggling, radiological security, export controls, reactor conversion, nuclear materials security and elimination, and research into the impacts of artificial intelligence on nuclear threats.

In a March 11 statement opposing the continuing resolution, Rep. Bill Foster (D-Ill.) said the funding cut “would substantially affect our national security, paving the way for countries like Iran, terrorist groups, and other adversaries to more easily get their hands on nuclear material.”

The continuing resolution, which President Donald Trump signed into law March 15, included several other changes to the previous year’s funding levels. The annual budget for the Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine program was increased to $9.6 billion, on the heels of an initial plus-up to $8.9 billion in a December short-term continuing resolution. (See ACT, January/February 2025.)

In nonbinding funding tables accompanying the new resolution, appropriators suggested that the Pentagon cut $640 million from the budget for the Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile program and its warhead, reflecting ongoing delays. (See ACT, September 2024.) The appropriators also suggested a $150 million budget for initial work on the nuclear-capable, sea-launched cruise missile, down from the $252 million authorized in December by Congress in the now-abandoned fiscal 2025 budget process. (See ACT, January/February 2025.)

The continuing resolution was negotiated by the House Republican majority and passed largely on a party-line vote in the lower chamber. Senate minority Democrats split on the resolution, providing enough votes to bring the measure to a vote and ensuring its passage.