"I greatly appreciate your very swift response, and your organization's work in general. It's a terrific source of authoritative information."

Trump Could Make His Mark With a New Iran Deal

December 2024

By Ellie Geranmayeh

When U.S. President-elect Donald Trump reenters the White House, he faces the most advanced Iranian nuclear program to date.1 Iran now has enough fissile material to produce three bombs within weeks. This proliferation threat exists within a Middle East that is on high alert, with Israel and Iran on the brink of wider conflict. These realities could drag U.S. forces into further military operations, just as the incoming president pledged to end the wars in this region.

In his first term, Trump backed his hawkish advisers to pursue a “maximum pressure” policy aimed at throttling Iran’s economy. Trump was wrongly sold on the idea that this approach would bring Iran to its knees and result in a capitulation to U.S. demands at the negotiating table. Instead, Tehran expanded its nuclear program and ratcheted up attacks against U.S. forces.

Rather than making a deal with the United States, as Trump hoped, Iran is now increasingly aligned with and economically dependent on China and Russia. Despite U.S. efforts to isolate Iran in the region, the Arab monarchies in the Middle East have pursued rapprochement with Tehran. In short, maximum pressure badly backfired.

The Ball in Trump’s Court

Following the Gaza war and the sharp uptick in military confrontation between Israel and Iran since April 2023, Iran seems to have edged toward a new ultimatum for the incoming Trump administration. Either Trump is dragged into the simmering war between Israel and Iran, or he cuts a deal with Iran that creates a cold peace.

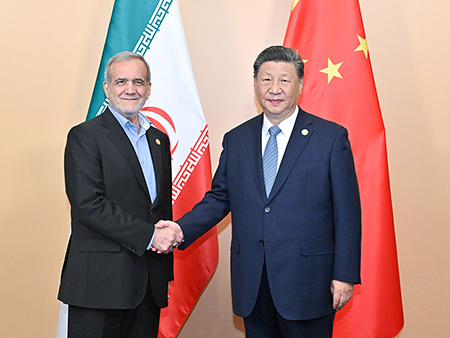

Since the U.S. election, Iranian officials have signaled openness to a direct political track with the Trump administration, warning that a return to a maximum-pressure 2.0 approach “will only result in ‘maximum defeat 2.0.’”2 Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei seems to have given the green light for the new government of President Masoud Pezeshkian to test new direct negotiations with Washington over the nuclear program. Although it is possible that Khamenei may eventually retrench or undermine this track, for now the ball is in Trump’s court.

During recent campaigning, Trump repeated his desire to cut a deal with Iran. The major unknown is what path he might choose to get to the negotiating table. Trump could choose to repeat the mistakes of his first term by allowing his hawkish foreign policy advisers to double down on maximum pressure policies.

A second, untested option: Trump can use the first 100 days of his administration to open a direct diplomatic channel to Tehran and begin a dealmaking process in ways that President Joe Biden was unable to do. The reported meeting following the U.S. elections between Elon Musk, a member of Trump’s inner circle, and Iran’s envoy to the United Nations could pave the way to advancing this track once Trump takes office.3 Such an opening by itself could help cool the conflict between Israel and Iran immediately and freeze the Iranian nuclear program.

Getting to a Political Process

To get to a political process once Trump is in office, Iran and Trump’s transition team should carefully consider and plan to quickly agree on three key points. First, the two sides need to decide on the format for talks. Iran and the United States usually have used intermediaries, such as European and Arab countries, or multilateral settings such as the P5+1 to negotiate.4 Given tensions between European countries and Russia over the war in Ukraine, that format can no longer be used for near-term talks regarding Iran. The possibility for direct Iranian-U.S. talks should not be ruled out, and Tehran increasingly is signaling that it sees the value in such a format.5

In his first term, Trump’s preference was also for a direct, high-level meeting with Iranian counterparts.6 Back then, this option was unacceptable to Iran, given Trump’s decision to withdraw from the 2015 nuclear accord. It will be even more difficult now for Tehran to accept a meeting with Trump at the onset of talks given his decision to order the assassination of Iranian General Qassem Soleimani in 2020.

Yet, given the latest messaging from Tehran and the meeting with Musk, Iran could be persuaded to advance negotiations with a high-ranking U.S. official and then to finalize the talks at the presidential level. A leader such as Saudi Arabian Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who is close to Trump and is pursuing an important détente with Tehran, could push the two sides to undertake such talks.

Second, Iran and the United States need to decide the agenda and priorities for negotiations. The two sides are at odds over many topics, from nuclear proliferation, their respective military postures in the Middle East, human rights, and Iranian military support to Russia. A major question is whether Trump would seek to isolate Iran’s nuclear program as the highest threat to U.S. national security or take a grand bargain approach.

Neither approach is easy, nor will it lead to satisfactory results. Given the gravity of current tensions and past experience, however, Iran and the United States are unlikely to be able to negotiate a grand bargain. The two sides can unlock better progress by endorsing two parallel yet distinct tracks. The first track should focus on Iran’s nuclear program and entail trade-offs between Iran and the United States. The second track, which should be simultaneous, must intensify the ongoing regional deescalation negotiations with Iran led by Saudi Arabia. Both tracks should seek to bring Iran and Israel back from the brink of war, while acknowledging that the two countries will continue their shadow conflict in the near term.

Finally, at the onset of nuclear talks, Iran and the United States should agree on the immediate and medium-term endgame for negotiations. If, as some administration officials demanded in Trump’s first term, the objective is to get Iran to accept zero nuclear enrichment, the diplomatic process will deadlock quickly.7

A Chance for a New Path

Given robust advances to Iran’s nuclear program, Trump’s immediate goal should be to freeze the program and prevent weaponization activities. It is urgent that Tehran agree to increased international monitoring and supervision over its nuclear activities. This should be coupled with an understanding that Iran and the United States will not target one another militarily and that the simultaneous regional track must progress positively.

In the medium term, Washington should seek to roll back Iranian nuclear capabilities and activities. Although the 2015 nuclear accord can provide a framework, the final agreement will be a new Trump deal with Tehran. This likely requires at least one year of negotiation and possibly four to six months of implementation.

Iran’s new government has prioritized economic recovery and will require a measure of economic relief for each nuclear step. In the near term, a political thaw with the United States would ease the economic situation inside Iran by stabilizing the currency, but Iran will not take costly steps to wind down its nuclear program if the U.S. offer for economic relief is empty. Trump seems to have acknowledged the need to provide Iran with sanctions relief.8

Trump can ease sanctions on Iran through executive orders and nonenforcement. In the immediate term, given the president-elect’s economic tensions with China, one attractive proposition could be to permit the sale of Iranian oil to markets other than China, with the revenues set aside for a specific use and overseen by the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

Even under U.S. sanctions, Iran exports more than 1.5 million barrels of oil per day, almost all to China.9 Iran is believed to be doing this through sanctions-busting routes operated by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and often at a steep discount to China, without ease of access to hard currency from such sales. If Iran could export oil without falling foul of U.S. sanctions, it could find potential buyers elsewhere at higher prices. Easier access to oil revenues also will be an attractive proposition for the Iranian government.

In the medium term, as part of a new nuclear deal with Iran, the United States could look to bring on board Arab partners, such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Iraq to provide economic relief to Iran. This would be a way to weave together the nuclear and regional tracks of negotiations with Tehran.

Trump instinctively wants a deal with Tehran. He has stated that he is not interested in regime change in Iran, but he wants a deal to ensure Iran does not possess nuclear weapons and is prepared to lift sanctions.10 Yet, it is evident that many will try to block any deal. Chief among them are Trump’s foreign policy advisers, some donors, and the Israeli government. All are pushing Trump to revert back to maximum pressure, arguing that this will “bankrupt” Iran and deprive it of resources to pursue its nuclear and regional goals.11

Continuing down such a confrontational path will bring Trump closer to his nightmare scenario: an Iranian nuclear bomb, an Israeli-Iranian war, and an entrenched U.S. military presence in the Middle East. If instead, Trump follows his gut instincts on dealmaking, quells Israeli opposition, and gets buy-in from the Republican majority in Congress, he can chart a new direction on policy toward Iran in ways that no other U.S. president has managed.

ENDNOTES

1. Stephanie Liechtenstein, “Iran Defies International Pressure, Increasing Its Stockpile of Near Weapons-Grade Uranium, UN Says,” Associated Press, November 19, 2024.

2. Najmeh Bozorgmehr and Bita Ghaffari, “Iran Keeps the Door Open to Talks With Donald Trump,” Financial Times, November 18, 2024; Seyed Abbas Araghchi (@araghchi), X, November 12, 2024, https://x.com/araghchi

/status/1856413334699983297.

3. Farnaz Fassihi, “Elon Musk Met With Iran’s U.N. Ambassador, Iranian Officials Say,” The New York Times, November 14, 2024.

4. The P5+1 comprises China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and Germany. They jointly negotiated the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran.

5. “Iran’s President Says Tehran Has to Deal With Washington,” Reuters, November 12, 2024.

6. Robin Wright, “Trump’s Close-Call Diplomacy With Iran’s President,” The New Yorker, September 30, 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/donald-trumps-close-call-diplomacy-with-irans-president-hassan-rouhani.

7. “After the Deal: A New Strategy,” Heritage Foundation, May 21, 2018, https://www.heritage.org/defense/event/after-the-deal-new-iran-strategy.

8. “Trump on Sanctions,” C-SPAN, November 18, 2024, https://www.c-span.org/video/?c5142328.

9. Clayton Thomas, Liana W. Rosen, and Jennifer K. Elsea, “Iran’s Petroleum Exports to China and U.S. Sanctions,” Congressional Research Service Insight, IN12267, November 8, 2024, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN12267#:~:text=Iran’s%20petroleum%20exports%20reportedly%20reached,furtherance%20of%20U.S.%20foreign%20policy.

10. PDB Podcast, “Donald Trump Gets Emotional - Speaks on Tariffs, Obama and Iran,” YouTube, October 17, 2024, https://www.youtube.com/clip/UgkxkgQXjYimUvMRxutLHPy8J116KZKYDsWo; Kierra Frazier, “Trump Makes Surprising Overture to Iran at NYC Press Conference,” Politico, September 26, 2024, https://www.politico.com/news/2024/09/26/trump-iran-nyc-press-conference-00181367; “Trump on Sanctions.”

11. Felicia Schwartz and Andrew England, “Trump Team Aims to Bankrupt Iran With New ‘Maximum Pressure’ Campaign,” Financial Times, November 16, 2024.

Ellie Geranmayeh, the deputy head of the Middle East and North Africa program at the European Council on Foreign Relations, focuses on European and U.S. policies related to Iran’s nuclear program and regional activities.