“For 50 years, the Arms Control Association has educated citizens around the world to help create broad support for U.S.-led arms control and nonproliferation achievements.”

How Will Trump Balance South and North Korea This Time?

December 2024

By Jenny Town

There is great anxiety among U.S. allies and partners about how U.S. President-elect Donald Trump’s second administration will approach alliance management. The potential return to transactional relations raises questions about what new price will be placed on continued partnership and whether countries should pay it. South Korea, in particular, felt the brunt of this treatment during Trump’s first term and is bracing for whatever new demands may come next.

Trump already has taken note of the fact that the South Korean-U.S. Special Measures Agreement, which determines the cost sharing of maintaining U.S. troops on the Korean peninsula, was renegotiated early, presumably to avoid the kind of inflationary pressures that were likely under Trump. The new agreement, concluded in October, raises South Korea’s cost commitment by 8.3 percent to $1.47 billion for 2026.1 The announcement drew criticism from then-candidate Trump, who claimed, “If I were there [in the White House] now, they would be paying us $10 billion a year,” and asserted that the South Koreans “would be happy to do it. It’s a money machine, South Korea.”2

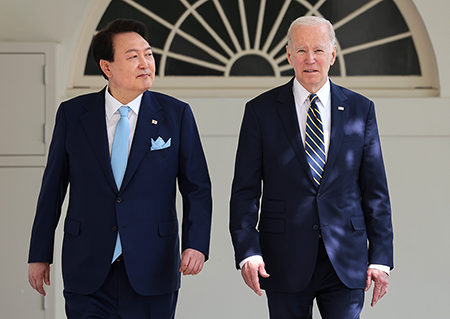

This reaction has concerned many South Korean officials who worry that Trump will push to renegotiate the agreement after he takes office. Whether he will have advisers around him who are willing to curb this impulse is unclear. If not, how South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol responds to such pressures will set the tone for relations going forward.

If South Korea is forced to renegotiate the agreement, it likely will comply and raise contributions further to some degree, but demand a trade-off in return. The most likely trade-off would be a South Korean demand to renegotiate the South Korean-U.S. nuclear cooperation agreement to grant Seoul enrichment and reprocessing rights.

South Korea has sought this approval for decades for its nuclear energy industry to improve its self-sufficiency and competitiveness and to help manage the industry’s growing spent fuel storage challenge. Although this ambition is largely for peaceful nuclear energy purposes, the intensifying debate in Seoul over whether the country should develop its own nuclear weapons raises serious questions about its intentions toward enrichment and reprocessing activities and undermines its otherwise notable commitment to nonproliferation.

On the North Korea front, Trump is likely to defer direct action in the near term. Ending the war in Ukraine appears to be more of a top priority for him, along with setting the tone for Chinese-U.S. relations. Yet, both of these efforts could have an indirect impact on North Korea, especially its increasingly close relationship with Russia. For instance, conditions about Russia’s relations with North Korea may well be included in any negotiation on Ukraine, thus testing how deeply Russian President Vladimir Putin is invested in keeping North Korea close.

Arguably, Putin would find it more difficult to abandon Pyongyang now that North Korean lives are being sacrificed on Moscow’s behalf. Should an agreement on Ukraine sever, for instance, even just North Korean-Russian military cooperation, this would be well received in South Korea, easing some anxiety over Russia’s potential assistance in improving or advancing Pyongyang’s weapons of mass destruction capabilities. Yet, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un is not likely to take this well after being a loyal partner to Putin throughout his illegal war and signing into law the treaty to codify their partnership, including in the military sphere.

While trying to set a new Chinese-U.S. agenda, Trump may also try to lean on Chinese President Xi Jinping to help moderate North Korea’s behavior, as the U.S. leader did early in his first term. This time, however, such an effort likely would be in vain. Beijing’s influence over Pyongyang has been greatly diminished in recent years as Moscow’s has risen. A change in North Korean-Russian relations could alter that dynamic, but not overnight and probably not to the degree it would take for China to become a credible broker.

More importantly, Xi has been burned by Trump on this issue. In 2017, Xi agreed to help Trump with North Korea in exchange for not being labeled a currency manipulator and avoiding a trade war with the United States. China did more that year under the maximum pressure campaign than ever before, but despite these efforts, Trump began to gradually impose a series of new tariffs on Chinese imports in 2018 and 2019, triggering retaliatory tariffs from China; and in August 2019, the U.S. Department of the Treasury designated China a currency manipulator.3 Whatever room there may be for Chinese-U.S. cooperation in the current geopolitical environment, North Korea is not the “easy place” to start.

In the meantime, although Trump may think he has time to defer dealing directly with North Korea until he is ready, Kim may not afford him that luxury. Already, North Korea has called for the “limitless” expansion of its nuclear program.4 Earlier this year, it revealed a large uranium-enrichment facility, underscoring its ability to ramp up nuclear weapons production, and flight-tested a new, larger intercontinental ballistic missile.5

So far, presumably for political reasons, North Korea has refrained from additional nuclear weapons testing, despite having at least one untested warhead design. That restraint certainly could be lifted if Kim feels betrayed by his current closest ally to demonstrate his willingness and ability to carry on without outside support. Further progress on reconnaissance satellites, multiple warheads, and reentry vehicle technologies also are expected.

North Korea also could turn more inward to accelerate plans already in motion. Kim has renounced peaceful unification, designated South Korea a hostile state, and severed inter-Korean transportation infrastructure and is working to make permanent North Korea’s sovereignty. Recent references to fortifying the “southern border” suggests further changes are coming that are likely to challenge the legacies of the Korean War, such as the persistence of the Demilitarized Zone itself.6

Questions about whether aspects of the 1950-1953 Korean War Armistice Agreement, such as the continuation of the Demilitarized Zone versus a transition to more normal border management protocols, should be up for piecemeal renegotiation outside of a formal peace treaty process and are likely to come up sooner rather than later. Seoul is unlikely to be willing to negotiate on such matters, but Trump may not dismiss the proposition so easily. Disagreement on how to respond to such a challenge may cause a major rift in South Korean-U.S. relations and renew calls in South Korea for its own nuclear armament.

Under normal circumstances, North Korea’s risk tolerance for taking actions that provoke South Korea and the United States has been consistently higher than what either Seoul or Washington could conceive of doing in return. Even during the “fire and fury” days of the first Trump administration, there was a lot of a fury, but no fire.7 Will that remain true?

Trump seems to believe he has a good relationship with Kim already and that he can take his time.8 North Korea may test him early if only to underscore Kim’s strengthened position this time around. Whether Trump in his second term will be more or less risk tolerant on the Korean peninsula is still an open and worrisome question.

ENDNOTES

1. Young Gyo Kim, “Experts: Future of U.S.-South Korea Defense Cost-Sharing Deal Remains Uncertain,” Voice of America, October 11, 2024, https://www.voanews.com/a/experts-future-of-us-south-korea-defense-cost-sharing-deal-remains-uncertain-/7819599.html.

2. Julian Ryall, “South Korea Shocked by Trump’s ‘Money Machine’ Plan,” Deutsche Welle, October 22, 2024, https://www.dw.com/en/south-korea-shocked-by-trumps-money-machine-plan/a-70564833.

3. Inhan Kim, “Trump Power: Maximum Pressure and China’s Sanctions Enforcement Against North Korea,” The Pacific Review, Vol. 33, No. 1 (2020): 96-124; Danielle Paquette, David J. Lynch, and Emily Rauhala, “As Trump’s Trade War Starts, China Vows Retaliation,” The Washington Post, July 6, 2018; U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Designates China as a Currency Manipulator,” press release, August 5, 2019, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm751.

4. Kim Tong-Hyung, “North Korean Leader Calls for Expanding His Nuclear Forces in the Face of Alleged U.S. Threats,” Associated Press, November 17, 2024.

5. Olli Heinonen et al., “First Look at North Korea’s Uranium Enrichment Capabilities,” 38 North, September 13, 2024, https://www.38north.org/2024/09/first-look-at-north-koreas-uranium-enrichment-capabilities/; Vann H. Van Diepen, “North Korea Tests New Solid ICBM Probably Intended for MIRVs,” 38 North, November 5, 2024, https://www.38north.org/2024/11/north-korea-tests-new-solid-icbm-probably-intended-for-mirvs/.

6. “North Korea Vows to Block and Fortify Border With South,” Deutsche Welle, October 9, 2024, https://www.dw.com/en/north-korea-vows-to-block-and-fortify-border-with-south/a-70447450.

7. John Walcott, “Trump’s ‘Fire and Fury’ North Korea Remark Surprised Aides: Officials,” Reuters, August 9, 2017.

8. Simone McCarthy, “Trump Claims Kim Jong Un ‘Misses’ Him. But He Faces a Very Different North Korean Leader This Time Around,” CNN, November 8, 2024, https://www.cnn.com/2024/11/08/asia/trump-kim-jong-un-north-korea-intl-hnk/index.html.

Jenny Town is a senior fellow at the Stimson Center and the director of the center's Korea Program and 38 North publication.