Dangerous Parallax: Chinese-U.S. Nuclear Risks in Trump’s Second Term

December 2024

By Tong Zhao

Following President Donald Trump’s reelection, China anticipates a more confrontational U.S. policy and is bracing for intensified strategic competition. Beijing is likely to double down on bolstering its nuclear arsenal, emphasizing the Chinese military Rocket Force mission of “strategic counterbalance,” the use of strategic military capabilities to moderate adversaries’ broader approaches toward China.

During Trump’s first term, the Chinese leadership came to view the United States as an existential threat, not primarily due to changes in U.S. nuclear policy but because of a severe deterioration in bilateral relations broadly. This has driven Beijing to rely increasingly on the perceived coercive power of nuclear weapons to stabilize its overall relationship with Washington. In Trump’s second term, non-nuclear tensions may escalate further through systematic economic decoupling and heightened geopolitical confrontation.

In the nuclear domain, U.S. patience with China is wearing thin. Beijing’s unwillingness to explain or constrain its nuclear buildup has prompted Washington to consider significant enhancements to U.S. nuclear capabilities. Owing to its deep-rooted siege mentality, China likely will interpret these measures as further evidence of U.S. “hegemonic” ambitions rather than responses to its own actions. Beijing may become more convinced that Washington is actively pursuing a disarming first-strike capability.

The second Trump presidency likely will revive strict visa and security measures, thus constraining personnel exchanges between the two countries. The resulting decline in dialogue between nuclear policy experts could lead both sides to embrace more pessimistic interpretations of each other’s nuclear capabilities, goals, and strategic designs.

Compounding the challenges, Washington’s internal policy environment under the new administration is likely to be highly polarized. Fierce clashes between “pro-deterrence” and “pro-arms control” advocates could lead to intense criticism of many of the administration’s nuclear policy decisions. This internal discord could lead Beijing to view the U.S. political landscape as too unstable for meaningful long-term engagement and thus further entrench its resistance to engaging in substantive strategic dialogue with Washington. Paradoxically, fierce domestic opposition to Trump’s nuclear policies also might amplify unintentionally China’s internal narrative, which fixates on U.S. policy flaws, making Beijing even less likely to recognize its share of responsibility for rising tensions.

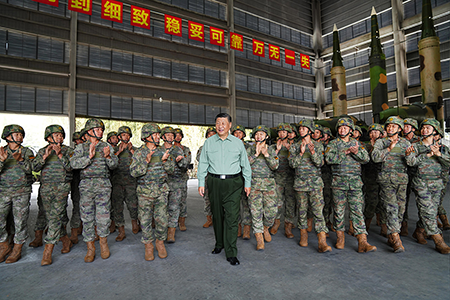

The next four years mark a critical juncture in the nuclear paths of both nations. As the Trump administration sets the direction of U.S. nuclear enhancement, China also enters a critical phase of its own nuclear development. Having restructured the Rocket Force leadership, Chinese President Xi Jinping now emphasizes “strengthening targeted training with new equipment, skills, and combat methods.”1 In the coming years, the Rocket Force likely will prioritize developing operational doctrines that define how to employ its expanded capabilities. This process will determine whether and to what extent the leadership’s focus on “combat capabilities” evolves into a more pronounced war-fighting doctrine for its nuclear forces.

A particularly volatile issue lies in the two countries’ approaches to theater-range nuclear forces. Potential U.S. efforts to increase the number of warheads on intercontinental delivery systems may draw attention, but it is the possibility that the United States might deploy tactical nuclear weapons in the Asia-Pacific region that raises greater alarm in China. The second Trump presidency overlaps with Xi’s reported timeline for developing sufficient military capabilities to overtake Taiwan. As the U.S. and Chinese militaries intensify preparations for a Taiwan contingency, they also are conducting increasingly detailed planning for nuclear deterrence in regional conflicts. Each side seeks the ability to manage nuclear escalation if deterrence fails, attempting to prevent unlimited nuclear exchange while securing advantageous terms for ending the conflict.

Once started, competition in escalation management propels rivals into a destabilizing spiral of increasingly diverse and expanding nuclear arsenals. The scarcity of authoritative information about operational military planning on both sides fuels excessive threat perception. It is also difficult to prevent competition that begins at lower rungs of the escalation ladder from expanding upward to higher levels, further increasing the likelihood of a full-scale arms race.

Failure to appreciate action-reaction dynamics heightens these risks. China has assumed mistakenly that its nuclear expansion, including its massive development of increasingly accurate theater-range nuclear-capable missiles, would not provoke responses from other powers. Many U.S. experts also downplay the likelihood that U.S. efforts to enhance low-yield nuclear weapons and forward-deployment capabilities will intensify China’s threat perception and trigger additional countermeasures.

The Trump administration appears prepared to advocate for the expansion of tactical nuclear capabilities, believing that perceived weaknesses in this area could embolden China to consider nuclear first use in a regional conflict. Yet, there is no evidence in Chinese writings or analysis that the Chinese military perceives such weaknesses in U.S. nuclear capabilities. On the contrary, Chinese military analysts are focused predominantly on what they see as a growing U.S. interest in lowering the nuclear threshold and preparing for limited nuclear wars. This perception in turn has driven China’s investments in limited nuclear retaliation and escalation management capabilities.

Likely destabilizing the situation further is the erosion of the global nonproliferation regime. Trump’s anticipated rollback of U.S. security commitments to allies and partners has sparked concerns that countries such as South Korea might pursue nuclear weapons technology. Some U.S. experts are suggesting that Ukraine consider developing its own nuclear weapons option if it cannot secure adequate external security guarantees such as NATO membership. Any shift toward tacitly endorsing such “friendly proliferation” would dismantle decades of nonproliferation norms and remove crucial guardrails in Chinese-U.S. competition. Beijing might interpret this as confirmation that foundational international norms have lost their relevance.

In this climate, convincing China that the Australian-UK-U.S. nuclear submarine program is not a pathway to Australian nuclear weapons development would be much more difficult. It also would be difficult to foresee how Beijing might recalibrate its stance on nuclear nonproliferation in response. Before introducing radical changes with unpredictable consequences, Trump should engage Xi directly on two key issues: initiating serious arms control discussions and addressing how China’s passivity toward Russian aggression and North Korean provocations fuel nuclear proliferation, ultimately undermining China’s own strategic interests.

Confronted with unprecedented risks of nuclear arms races and proliferation, Chinese and U.S. nuclear policy experts carry a historic responsibility to assess critically their respective leaders’ policy choices.

Thoughtful debate on the long-term consequences of their own country’s policies, coupled with a nuanced understanding of their rival’s perspective, is essential to avoiding the catastrophic outcomes of strategic miscalculations.

ENDNOTES

1. “Xi Urges Strategic Missile Troops to Enhance Deterrence, Combat Capabilities,” Xinhua

News Agency, October 19, 2024, https://english.www.gov.cn/news/202410/19/content_WS67136968c6d0868f4e8ec184.html.

Tong Zhao is a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, working for the Nuclear Policy Program and Carnegie China.