“For 50 years, the Arms Control Association has educated citizens around the world to help create broad support for U.S.-led arms control and nonproliferation achievements.”

The Biden administration’s $850 billion defense budget request for fiscal year 2025 would increase spending for Pentagon nuclear weapons programs by 31 percent over the current year.

April 2024

By Xiaodon Liang

The Biden administration’s $850 billion defense budget request for fiscal year 2025 would increase spending for Defense Department nuclear weapons programs by 31 percent over the current year and projects sharply rising future costs for some key nuclear modernization programs.

The request for National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) weapons-related activities is 4 percent higher than appropriated by Congress for fiscal year 2024. In all, the budget request, unveiled on March 11, calls for $69 billion for nuclear weapons operations, sustainment, and modernization, including $49 billion for Pentagon programs and the rest for the NNSA. The combined budgets would be 22 percent higher than last year.

The request for National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) weapons-related activities is 4 percent higher than appropriated by Congress for fiscal year 2024. In all, the budget request, unveiled on March 11, calls for $69 billion for nuclear weapons operations, sustainment, and modernization, including $49 billion for Pentagon programs and the rest for the NNSA. The combined budgets would be 22 percent higher than last year.

Three key nuclear rearmament programs are driving increasing costs. The funding request for the new Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) system foresees lifetime research and development (R&D) and procurement costs that are 44 percent higher than anticipated in the 2024 budget request. The Columbia-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine program will consume 30 percent of the Navy’s $32 billion shipbuilding budget under the administration’s spending plan for 2025, up from 17 percent in the budget authorized by Congress for 2024.

Meanwhile, the cost of producing plutonium pits at the 80-unit-per-year rate mandated by Congress is projected to rise to more than $4 billion per year from fiscal years 2027 to 2029.

The administration released the new budget request before Congress completed work on the appropriations bills that actually fund the government for the current fiscal year. Congressional negotiators finalized the fiscal 2024 appropriation figures for the Defense Department in late March.

In line with the Air Force’s disclosure in January that the Sentinel ICBM program likely would exceed baseline unit costs by 37 percent and its entry into service would be delayed by two years, the president’s request substantially raised projected R&D spending associated with the program. (See ACT, March 2024.) Last year, the R&D costs for fiscal years 2025 to 2028 were estimated at $11 billion, and now that projection is $14 billion.

Speaking at an industry conference March 7, Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall acknowledged the budgetary squeeze created by the cost overruns. “We see very big problems dealing with [fiscal] ‘26. We're looking at a number of things which are increasing. Sentinel is one of them,” he said.

The Air Force requested $539 million in advance-year procurement money on the Sentinel program in 2024, but later asked congressional appropriators to shift that money to R&D. There is no further procurement request in the 2025 budget. In 2020 the Pentagon estimated that the total cost of the next-generation Sentinel program, including decades of operations and support, could be as high as $264 billion. (See ACT, March 2021.) Taking the new increases into account, the total cost of the program over its planned 50-year life cycle could be as high as $300 billion, plus another $15 billion to produce the new W87-1 warhead for the missiles. (See ACT, March 2024.)

The cost overruns put the Sentinel program in “critical” breach of the Nunn-McCurdy Act, triggering a mandatory investigation into the root causes of the unanticipated cost increases. By mid-April, the Defense Department is required to give Congress an explanation of the cost increase, changes in the projected cost, changes in performance or schedule, and action taken or proposed to control growth.

The Sentinel program is in “deep trouble,” Rep. John Garamendi (D-Calif.) of the House Armed Services Committee and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) of the Senate Armed Services Committee wrote in a March 14 letter to Kristyn Jones, the acting undersecretary of the Air Force. The lawmakers called for a thorough assessment of alternatives to the Sentinel program, including possibly extending the life of the Minuteman III ICBM to 2030, 2040, or 2050.

Funding for the W87-1 warhead associated with the Sentinel ICBM would stay flat at $1.1 billion in 2025 under the administration’s budget proposal.

The request calls for $8 billion for R&D and procurement of the new long-range B-21 strategic bomber, slightly less than the 2024 appropriation. The Air Force would receive less for the Long-Range Standoff (LRSO) weapons system, a new nuclear-armed, air-launched cruise missile, with funding falling from the $950 million appropriated in 2024 to $833 million for 2025. Spending on the W80-4 warhead for the LRSO system would increase from $1 billion to $1.2 billion.

Spending on the Columbia-class submarine would increase sharply from $6.1 billion in 2024 to $9.8 billion in 2025. Several media outlets, citing unnamed sources, reported March 11 that the first ship would not launch until 2028, a year later than planned.

To address production challenges and delays affecting the Columbia-class submarine and the Virginia-class attack submarine programs, the administration asked for $3.3 billion in 2024 supplemental funding to invest in the submarine industrial base. Speaking in support of the supplementary request March 11, Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman Jack Reed (D-R.I.) called on contractors to “do better” and “get their personnel situation straightened out,” according to National Defense.

The budget also seeks $743 million for development of a new W93 submarine-launched ballistic missile warhead and its aeroshell, an increase above the $516 million that was appropriated by Congress in fiscal 2024.

The administration’s request did not include funding for the nuclear-capable sea-launched cruise missile despite the mandate in the 2024 National Defense Authorization Act that the administration establish a program of record for the system. Congress appropriated $90 million for the missile and $70 million for its warhead in the 2024 budget. (See ACT, January/February 2024.)

In the NNSA request, funding for plutonium-pit modernization and production at the Savannah River Site would increase from the $1.1 billion enacted by Congress in 2024 to $1.3 billion, while funding for the same activities at Los Alamos National Laboratory would decline from $1.8 billion to $1.5 billion. The NNSA significantly raised its projections for plutonium production and modernization costs for the 2025-2028 time period from $12.3 billion to $14.8 billion.

In a January 2023 report, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) assessed that the NNSA had not developed a comprehensive schedule or cost estimate for the plutonium modernization program that met GAO best practices. The GAO found activities and milestones missing from the NNSA schedule and flagged a likelihood of disruption and delay.

Meanwhile, spending on NNSA arms control and nonproliferation programs would increase from $212 million appropriated by Congress for 2024 to $225 million. The administration request for the Defense Department Cooperative Threat Reduction program would remain unchanged at $350 million.

Following testing setbacks and delays, the administration has eliminated funding for procuring the Navy’s hypersonic Conventional Prompt Strike system while requesting R&D spending of roughly $900 million. The Army variant of the system, the Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon, would receive $538 million in R&D funding and an additional $744 million for procurement under the proposed budget.

Two months after Congress eliminated funding for the Air Force’s Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon (see ACT, January/February 2024), the Biden administration increased its R&D request for the service’s other hypersonic program, the Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile. That program would receive $517 million in 2025, according to the budget proposal, up from $343 million appropriated by Congress for 2024.

Spending on missile defense programs would decline under the administration request, with total costs for the Aegis ballistic missile defense system and purchases of Standard Missile-3 Block IB and IIA interceptor missiles declining from the $1.7 billion appropriated last year to $1.3 billion.

Likewise, spending on design and development of the Missile Defense Agency’s Next Generation Interceptor, a new component of the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense system, would be reduced from the $2.1 billion appropriated in 2024 to $1.7 billion.

There is a strong case to be made that threats of nuclear weapons use are not only unacceptable and illegitimate but contrary to international law.

April 2024

By John Burroughs

Contradicting the widespread and complacent post-Cold War belief that the risks of the nuclear age are declining, threats of the possible use of nuclear weapons are on the rise.

In the summer and autumn of 2017, the United States and North Korea exchanged incendiary warnings of nuclear destruction.1 In September 2019, Pakistan referred to possible nuclear war in connection to its dispute with India over Kashmir.2 In recent months, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un on several occasions reiterated his country’s readiness to resort to nuclear arms to defend its fundamental interests.3 Most alarmingly, the Russian government on numerous occasions, beginning with President Vladimir Putin’s speech on February 24, 2022,4 and up to the present, has raised the possibility of resorting to nuclear weapons should the United States and its NATO allies intervene to defend Ukraine against the full-scale Russian invasion.

In the summer and autumn of 2017, the United States and North Korea exchanged incendiary warnings of nuclear destruction.1 In September 2019, Pakistan referred to possible nuclear war in connection to its dispute with India over Kashmir.2 In recent months, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un on several occasions reiterated his country’s readiness to resort to nuclear arms to defend its fundamental interests.3 Most alarmingly, the Russian government on numerous occasions, beginning with President Vladimir Putin’s speech on February 24, 2022,4 and up to the present, has raised the possibility of resorting to nuclear weapons should the United States and its NATO allies intervene to defend Ukraine against the full-scale Russian invasion.

Such threats are utterly unacceptable, above all because they greatly increase the risks of a humanitarian and environmental catastrophe resulting from use of nuclear weapons. The position adopted by the Group of 20 (G-20) states, an intergovernmental forum that includes the world’s major powers, in a declaration in Bali in November 2022 is striking in this regard. The declaration states in part, “It is essential to uphold international law and the multilateral system that safeguards peace and stability. This includes defending all the Purposes and Principles enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations and adhering to international humanitarian law, including the protection of civilians and infrastructure in armed conflicts. The use or threat of use of nuclear weapons is inadmissible.”5

Although that position clearly was occasioned by Russian nuclear threats, by its terms, it is not limited to that circumstance.6 It was repeated in another G-20 declaration in New Delhi in September 2023.

The Legal Dimension

Is a declaration of the “inadmissibility” of the threat and the use of nuclear arms an articulation of a political and moral norm, or does it also have a legal dimension? After all, the reference to inadmissibility does have a legal flavor; in a trial, evidence is found to be admissible or inadmissible. Further, there is a strong case to be made that threats of nuclear weapons use are not only unacceptable and illegitimate but contrary to international law. That is true under law governing when the resort to force is lawful (jus ad bellum) and under law governing the conduct of conflict (jus in bello), the law of armed conflict or international humanitarian law.

Article 2(4) of the UN Charter provides that “[a]ll Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.” If a use of force would violate Article 2(4), a threat to engage in such force violates that article. As the International Court of Justice (ICJ) stated broadly in its 1996 nuclear weapons advisory opinion, “The notions of ‘threat’ and ‘use’ of force under Article 2, paragraph 4, of the Charter stand together in the sense that if the use of force itself in a given case is illegal—for whatever reason—the threat to use such force will likewise be illegal.”7

It follows that a threat to use nuclear weapons as part of an aggressive attack is illegal. That certainly applies to the nuclear threats made in support of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

What is the law, though, when a state threatens to use nuclear arms not as part of an aggressive attack as in the Russian case? As the ICJ explained, the use or threat of force in self-defense pursuant to Article 51 of the Charter must be necessary and proportional.8 A defensive threat to use nuclear weapons that does not meet those criteria would be illegal under jus ad bellum. In this context,9 proportionality requires that the defensive use of force have a reasonable relationship to the aggressive act responded to and a reasonable relationship to the lawful goals of the defensive use of force, for example, expelling troops from the attacked state’s territory. In many or all circumstances, a defensive first use of nuclear weapons would not be necessary or proportionate as a matter of jus ad bellum. Notably, the ICJ observed that the risk of escalation must be taken into account in assessing proportionality.10 Recent North Korean nuclear threats fail to meet the requirement of proportionality.

The court also found that any threat to use nuclear weapons, whether aggressive or defensive, must be of a use that would comply with international humanitarian law or jus in bello. In general, the ICJ said that “[i]f an envisaged use of weapons would not meet the requirements of humanitarian law, a threat to engage in such use would also be contrary to that law.”11 Under that principle, if a use of nuclear arms is illegal, the threat of their use is illegal.

Putting aside marginal cases, nuclear use in typical scenarios, even if defensive, would be illegal under international humanitarian law.12 The ICJ went a long way toward accepting this conclusion, finding that “the threat or use of nuclear weapons would generally be contrary to the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict, and in particular the principles and rules of humanitarian law.”13 The court did not reach a conclusion, one way or the other, however, regarding an extreme circumstance of self-defense in which the very survival of a state is at stake.14 Nearly three decades after the court issued its opinion, the global community should move beyond the court’s uncertainty in that circumstance.

The ICJ Analysis of Threat

The ICJ analysis of UN Charter requirements barring aggressive or disproportionate threats of force is unexceptionable; it flows from the Charter and the well-established rule that a defensive use of force must be necessary and proportional. In contrast, the basis for the court’s finding that a threat to use weapons in violation of international humanitarian law is illegal is not clear from the advisory opinion, nor is such a principle readily ascertainable in treaty law or ICJ case law.

Yet, the proposition that threats of illegal force are themselves illegal is rooted in the most important modern treaty, the UN Charter. Although the Charter does not address directly the issue of whether the illegality of threats of illegal force extends to violations of international humanitarian law, it does imply that the legality of threat of force and the legality of use of force should be analyzed together. The court’s reference under Article 2(4) to the illegality of threats of uses of force when the latter are illegal “for whatever reason” is consistent with that implication.15 Moreover, the Article 2(4) prohibition of the threat of force inconsistent with the purposes of the UN provides some support for an analysis going beyond the prohibitions of aggressive or disproportionate threats. Purposes set out in Article 1 include the maintenance of peace and security and cooperation in solving problems of a humanitarian character and in promoting respect for human rights.

Beyond those Charter considerations, it appears that the court enunciated the principle that a threat to use weapons in violation of international humanitarian law is illegal on its own authority. The ICJ is the highest court in the world on general questions of international law, and its judges include eminent international lawyers. It is not unusual for the highest court in a judicial system to develop the law or, put another way, to make visible already existing principles.

Sometimes, there is a distinction made in international law between conduct preparatory to a wrongful act and the wrongful act itself, which is illegal or criminal. This tendency is visible in the crime of aggression included in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which provides that an individual may be convicted of “planning” or “prepar[ing]” for aggression, but only if a state “act of aggression” is actually committed. If this approach were taken in the realm of state responsibility, a threat would be illegal only if contrary to a treaty, as it is in the case of threats of aggression under the Charter.16

A threat to use weapons in violation of international humanitarian law, certainly a specific and credible threat, is different from preparatory conduct such as acquiring military capabilities enabling an aggressive attack. A thought exercise regarding biological and chemical weapons illustrates the soundness of the court’s finding. The use of biological weapons and the use of chemical weapons would be violations of international humanitarian law prohibitions of attacks with indiscriminate and uncontrollable effects.17 Further, a nearly universal convention, the Chemical Weapons Convention, prohibits the possession and use of chemical arms; another one, the Biological Weapons Convention, prohibits possession of biological arms, reinforcing an existing ban on their use. Should a specific and credible threat to use such arms be considered lawful? Going beyond the sphere of weapons, under the Genocide Convention, incitement, conspiracy, and attempt to commit genocide are prohibited but not threats. Yet, it seems highly doubtful that a specific and credible threat to commit genocide should be considered lawful.

There are partial international prohibitions of threat under international humanitarian law.18 A key instrument, Additional Protocol I to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, includes a provision prohibiting “acts or threats of violence the primary purpose of which is to spread terror among the civilian population.”19 Another provision prohibits threatening that there shall be no survivors.20

Such prohibitions can be viewed in two ways. One is that their partial character demonstrates the lack of a comprehensive prohibition of threats to use weapons in violation of international humanitarian law. The second is that they are expressions of an underlying principle, namely, that it is prohibited to threaten to carry out a prohibited act.21

The Evolution of International Law

The latter view is more consonant with the evolution of international law, recently illustrated by the 2017 negotiation of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) and the UN Human Rights Committee’s 2018 General Comment on the right to life. In that comment, the committee found that “[t]he threat or use of weapons of mass destruction, in particular nuclear weapons…is incompatible with respect for the right to life and may amount to a crime under international law.”22

The TPNW is the latest manifestation of the view of a majority of the world’s states that the threat or use of nuclear arms is illegal. Previously, such views were expressed in arguments to the ICJ and, regarding use, in numerous UN General Assembly resolutions going back to 1961.23 Moreover, beginning with the 1967 Treaty of Tlatelolco, non-nuclear-weapon states have negotiated regional nuclear-weapon-free-zone treaties with protocols that, when ratified, obligate the five nuclear-weapon states acknowledged by the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty not to use or threaten to use nuclear arms against members of the regional zones.24

In June 2022, five months prior to the adoption of the G-20 declaration in Bali, the first meeting of TPNW states-parties adopted the Vienna Declaration. In it, states-parties “stress that any use or threat of use of nuclear weapons is a violation of international law”; and they “condemn unequivocally any and all nuclear threats, whether they be explicit or implicit and irrespective of the circumstances.” The second meeting of states-parties, in New York City in late 2023, reiterated those points. The TPNW itself obligates states-parties “never under any circumstances” to “use or threaten to use nuclear weapons.” TPNW states-parties do not include any nuclear-armed states.

These developments further support the soundness of the court’s findings: threats to use weapons that violate international humanitarian law and therefore, at least as a general matter, threats to use nuclear weapons are illegal. It bears repeating as well that threats to use disproportionate force in self-defense are illegal, and the risk of escalation, obviously an acute concern when it comes to nuclear arms, must be taken into account in assessing proportionality.

Without attempting a definition of “threat” as a matter of international law, it can safely be stated that a specific and credible governmental statement making demands qualifies. Take a concrete context where the stakes are high, such as an armed conflict involving a nuclear-armed state; and the message is, if you do not refrain from doing X or if you do Y, we will resort to nuclear arms. That undoubtedly is a legally cognizable threat. It certainly describes Putin’s threat at the outset of the invasion of Ukraine, in which he expressed a readiness to resort to nuclear force should NATO states “interfere” in Russian military operations in Ukraine.

What about standing policies declaring a state’s readiness to resort to nuclear weapons when subjected to a nuclear attack and more generally when vital interests are stake? One could argue that specific threats are not involved in those policies and therefore they are not illegal. It is true that references to vital interests and similar formulations are vague. Yet, doctrinal signals that a nuclear attack may or will be met with a responsive or preemptive nuclear attack are focused and credible, even if not issued in an actual circumstance of potential use.

More broadly, if specific threats are illegal, that points toward the illegality and certainly the illegitimacy of the machinery and doctrines of nuclear deterrence. In its advisory opinion, the ICJ stated that it “does not intend to pronounce here upon the practice known as the ‘policy of deterrence.’”25 Yet, as the United States observed in its oral argument to the court, “it is impossible to separate the policy of deterrence from the legality of the use of the means of deterrence.”26

It is highly disturbing that nuclear threats are on the rise, in the Russian-Ukrainian conflict and elsewhere. Even so, there are positive trends, although their importance should not be overstated. It is encouraging that there has been a counterassertion of a norm against nuclear threats in G-20 summits, as well as in the TPNW meetings. It is also encouraging that the United States and other NATO states for the most part have refrained from any public nuclear threats in response to those made by Russia.

The norm against threatening the use of nuclear weapons has a firm legal foundation. It is imperative that governments and civil society strive to entrench it even more deeply in international and national understanding and practice.

ENDNOTES

1. John Burroughs and Andrew Lichterman, “Trump’s Threat of Total Destruction Is Unlawful and Extremely Dangerous,” InterPress Service, September 25, 2017.

2. “Pakistan’s Khan Warns of All-Out Conflict Amid Rising Tensions Over Kashmir; Demands India Lift ‘Inhuman’ Curfew,” UN News, September 27, 2019, https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/09/1047952. Earlier in the year, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi referred to India’s nuclear weapons capability in relation to tensions with Pakistan. Pallak Nandi and Vimal Bhatia, “Our nukes not for Diwali: PM Narendra Modi on Pakistan's N-threat,” The Times of India, April 22, 2019, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/elections/news/our-nukes-not-for-diwali-pm-on-pakistans-n-threat/articleshow/68982495.cms

3. Josh Smith, “Explainer: How Could North Korea Use Its Nuclear Weapons?” Reuters, December 20, 2023.

4. From the transcript provided by the Kremlin: “I would now like to say something very important for those who may be tempted to interfere in these developments from the outside. No matter who tries to stand in our way or all the more so create threats for our country and our people, they must know that Russia will respond immediately, and the consequences will be such as you have never seen in your entire history,” http://www.en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/67843.

5. “G20 Bali Leaders’ Declaration,” November 15-16, 2022, para. 4, http://www.g20.utoronto

.ca/2022/G20%20Bali%20Leaders-%20Declaration,%2015-16%20November%202022,%20incl%20Annex.pdf.

6. A February 24, 2024, declaration by the Group of Seven states (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States) is limited in its scope, stating, “Threats by Russia of nuclear weapon use, let alone any use of nuclear weapons by Russia, in the context of its war of aggression against Ukraine are inadmissible.” The White House, “G7 Leaders’ Statement,” February 24, 2024, para. 2, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/02/24/g7-leaders-statement-7/.

7. Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons, Advisory Opinion, 1996 I.C.J. 226, para. 47 (July 8), https://www.icj-cij.org/sites/default/files/case-related/95/095-19960708-ADV-01-00-EN.pdf.

9. The jus ad bellum requirement of proportionality differs from the international humanitarian law principle of proportionality, which requires that the collateral damage and injury resulting from an attack not be excessive in relation to the anticipated military advantage.

10. Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons, 1996 I.C.J. at para. 43.

12. See “End the War, Stop the War Crimes,” Lawyers Committee on Nuclear Policy, April 21, 2022, pp. 5-6, https://www.lcnp.org/s/4-21-22-russia-ukraine_lcnpstatement2.pdf; Charles J. Moxley Jr., John Burroughs, and Jonathan Granoff, “Nuclear Weapons and Compliance With International Humanitarian Law and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty,” Fordham International Law Journal, Vol. 34, No. 4

(2011): 595.

13. Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons, 1996 I.C.J. at para. 105(2)E.

16. The International Law Commission has taken this position, stating, “Some rules specifically prohibit threats of conduct, incitement or attempt, in which case the threat, incitement or attempt is itself a wrongful act.” Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 2001, Vol. 2, Part 2, A/CN.4/SER.A/2001/Add.1 (Part 2), 2007, p. 61.

17. In addition to general rules of international humanitarian law, an amendment to the Rome Statute, so far ratified by only a small number of states, specifically makes use of biological weapons a war crime. Article 8(2)(b)(xxvii). Use of chemical weapons arguably is specifically criminal under a provision of the Rome Statute setting forth the Geneva Gas Protocol prohibition of use of “asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases, and all analogous liquids, materials or devices.” Article 8(2)(b)(xviii).

18. Principles embedded in national legal systems are also relevant to determination of general principles of international law. U.S. jurisdictions, for example, prohibit threat or menacing in certain contexts. Thus a Colorado statute provides that “[a] person commits the crime of menacing if, by any threat or physical action, he or she knowingly places or attempts to place another person in fear of imminent serious bodily injury.” Colo. Rev. Stat. § 18-3-206. Under federal law, transmitting “in interstate or foreign commerce any communication containing any threat to kidnap any person or any threat to injure the person of another” is a crime. 18 U.S.C. § 875(c).

19. Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), June 8, 1977, 1125 U.N.T.S. 3, art. 51(2). The U.S. 2022 Nuclear Posture Review states that “longstanding U.S. policy is to not purposely threaten civilian populations and objects.” U.S. Department of Defense, “2022 Nuclear Posture Review,” October 27, 2022, p. 8, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.PDF#page=44. Taken on its face and separated from the realities of targeting military objectives, that statement is consistent with the prohibition.

20. Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, art. 40.

21. Jean-Marie Henckaerts and Louise Doswald-Beck, Customary International Humanitarian Law, Vol. I (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), p. 162.

22. UN Human Rights Committee, “General Comment No. 36 (2018) on Article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, on the Right to Life,” CCPR/C/GC/36, October 30, 2018, para. 66.

23. See UN General Assembly, “Declaration on the Prohibition of the Use of Nuclear and Thermo-Nuclear Weapons,” Res. 1653 (XVI), November 24, 1961.

24. Nuclear-weapon states’ ratifications of the protocols are far from complete and in some cases are heavily qualified. Also, within and outside the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, nuclear-armed states have provided negative security assurances, qualified in most cases, that they will not use and in some cases not threaten to use nuclear arms against non-nuclear-weapon states. The International Court of Justice unsurprisingly found that nuclear-weapon-free-zone treaties and their protocols and negative security assurances do not establish a comprehensive prohibition of the threat or use of nuclear weapons. Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons, 1996 I.C.J. at para. 63. See generally Anna Hood and Monique Cormier, “Nuclear Threats Under International Law Part 1: The Legal Framework,” NAPSNet Special Reports, March 1, 2024.

25. Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons, 1996 I.C.J. at para. 67.

26. Verbatim record, CR 95/34, November 15, 1995, p. 63, https://www.icj-cij.org/sites/default/files/case-related/95/095-19951115-ORA-01-00-BI.pdf.

John Burroughs is senior analyst for Lawyers Committee on Nuclear Policy and author of The Legality of Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons: A Guide to the Historic Opinion of the International Court of Justice. This article draws on the author’s remarks at the conference “Nuclear Weapons and International Law: The Renewed Imperative in Light of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine” on November 8, 2023.

This nightmare scenario is not now on the horizon, but what if a large asteroid ever is on an imminent collision course with Earth?

April 2024

By David A. Koplow

What should be done if it is discovered some day that a large asteroid is on an imminent collision course with Earth? In particular, should a nuclear weapon be employed to divert or destroy such a threat if no other remedies seem sufficient?

This nightmare scenario is not now on the horizon; no one has detected any imminent massive inbound celestial body. Yet, humanity cannot take too much comfort because even the best astronomy is unable to detect all significant asteroids in adequate time to prevent their impact and because the world currently possesses only a very limited capacity for doing anything effective about these dangers.

This nightmare scenario is not now on the horizon; no one has detected any imminent massive inbound celestial body. Yet, humanity cannot take too much comfort because even the best astronomy is unable to detect all significant asteroids in adequate time to prevent their impact and because the world currently possesses only a very limited capacity for doing anything effective about these dangers.

Any potential deployment of a nuclear device in orbit or beyond and the prospect a nuclear explosion in space would face enormous political, legal, and technical obstacles. Even if the unprecedented activity were undertaken entirely for the peaceful purpose of saving humanity from a sudden extraterrestrial threat, it would be deservedly controversial and complicated. Long-standing international legal restrictions, established to preserve nuclear stability and restraint on Earth, would be severely challenged by any nuclear anti-asteroid program.

There are four main components of this scientific, political, and legal dilemma: the scope of the potential asteroid problem, the currently inadequate array of technically feasible responses, the legal and policy impediments that would apply against any possible use of a nuclear explosive device for anti-asteroid protection, and a proposed reconciliation via adaptations in existing international law.

Dodging Asteroids

There are many millions of asteroids in the solar system, of widely varying size, composition, location, and trajectory. Most of them stay safely in the main asteroid belt between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, but as gravity, random collisions, and space weather exert chaotic influences, some asteroids adopt more widely erratic orbits, several of which could bring them uncomfortably close to Earth. An asteroid that approaches within 45 million kilometers of our planet’s orbit is categorized as a “near Earth object”; if it flies closer than 7.5 million kilometers and is larger than 140 meters in size, it is labeled a “potentially hazardous object.”1

Distressingly, a great many of these fast-flying, portentous objects remain totally undetected. NASA and its companion space agencies in other countries are engaged assiduously in the search for these celestial bodies, and hundreds of new specimens are identified each year. Additional resources, including telescopes on the ground and in space, are being deployed to enhance “space situational awareness.” Yet, asteroids are relatively small and dark on the cosmic scale, and they can be especially difficult to detect if they approach from the general direction of the sun, which obscures the efforts of Earth-based astronomers. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory maintains a vivid Asteroid Watch Dashboard, which displays tracking information about upcoming near approaches, usually several per month, identifying each asteroid’s approximate diameter and date of closest Earth proximity.2

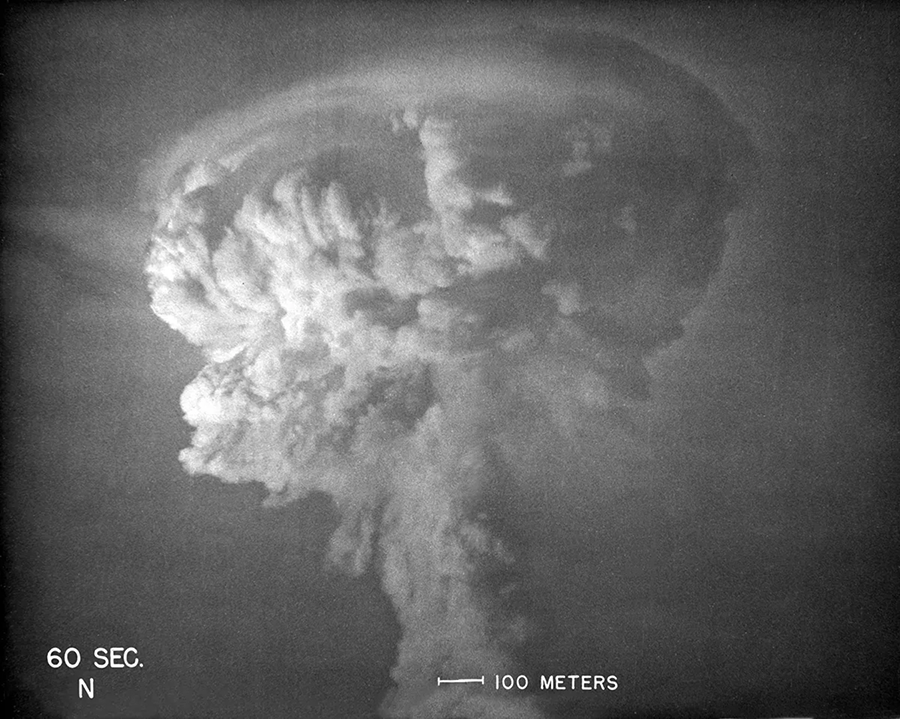

Generally, an asteroid larger than approximately 140 meters in diameter would be regarded as capable of inflicting regional damage, afflicting thousands of square kilometers, in a collision on Earth. There are an estimated 25,000 objects of this magnitude that could come near this planet, and only about 43 percent of them have been detected and tracked. A larger asteroid, measuring a kilometer or more across, would generate catastrophic global effects, comparable perhaps to those envisioned as the abrupt “nuclear winter” climatic alterations that could be triggered by a nuclear war. Some 854 of those giants have been detected, and dozens more are suspected.3

Throughout history, substantial asteroid impacts have been a recurrent phenomenon for this planet. Most famously, during the Chicxulub event some 66 million years ago, an asteroid 10-15 kilometers in diameter crashed into what is now the Gulf of Mexico, off the Yucatan Peninsula. The catastrophic geophysical effects led to the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs and perhaps 75 percent of all other animal and plant species living then.4

More recent episodes, involving much smaller asteroids, also have proven momentous. For example, in 1908, an asteroid perhaps 50 meters in diameter exploded above the Russian region of Tunguska. There were no documented human witnesses in that remote Siberian locale, but the force of the detonation has been estimated as equivalent to 10-50 megatons of TNT. It flattened 80 million trees over a 2,000-square-kilometer area.5

More recent episodes, involving much smaller asteroids, also have proven momentous. For example, in 1908, an asteroid perhaps 50 meters in diameter exploded above the Russian region of Tunguska. There were no documented human witnesses in that remote Siberian locale, but the force of the detonation has been estimated as equivalent to 10-50 megatons of TNT. It flattened 80 million trees over a 2,000-square-kilometer area.5

In 2013, near the Russian city of Chelyabinsk, a roughly 18-meter-wide asteroid exploded at an altitude of 30 kilometers with a yield estimated at 400-500 kilotons, damaging 7,200 buildings and injuring 1,500 people.6 No one had seen this asteroid coming, and as it streaked across the morning sky, it could have been misinterpreted as a U.S. missile.

Of course, smaller particles penetrate Earth’s atmosphere all the time, including the spectacular meteor showers that regularly illuminate the night sky. The passage of larger objects, a meter or more in size, dazzles observers somewhere on the planet three or four times per month. More ominous are the very close approaches by still-larger bodies that observatories continuously track. Although none are projected to impact Earth in the foreseeable future, these calculations remain largely a cosmic game of uncertainties and probabilities, given the difficulty of accurately projecting the future course of a distant asteroid or comet. Even if a potential threat is discerned sufficiently early, it may take many months and carefully repeated observations to determine how likely an Earth impact really is, where on the planet it might occur, and how large and solid and therefore how consequential the asteroid would be.

As one vivid example, the asteroid denominated as 99942 Apophis has a diameter of approximately 340 meters. Initial observations in 2004 indicated a 2.7 percent probability that it would collide with Earth in 2029, which would be extraordinarily damaging. Subsequent observations eliminated that possibility, but also assessed that if the 2029 flyby happened to pass within a narrow region in space characterized as a precise “keyhole,” then gravitational effects would imply that the asteroid’s next close approach to Earth, projected in 2036, would create such an impact. Subsequent additional observations have eliminated the likelihood of a collision; the 2029 conjunction will pass very near Earth, but the 2036 rendezvous will miss our planet by millions of miles, and there is now no prospect of a collision for at least the next 100 years.7

Nonetheless, other significant asteroids have replaced Apophis atop the International Astronomical Union’s Torino Scale, which categorizes asteroid impact dangers.8 In fact, between 2027 and 2029, five other, even larger asteroids will approach Earth to within only four times the distance to the moon. Ominously, astronomers warn that a doomsday collision is statistically a question of when, not whether, because large asteroids will surely collide with Earth at some point as they have in the past. They just do not know whether the next Chicxulub-scale impactor will arrive within a few decades or not for another 60 million years.

Planetary Defense

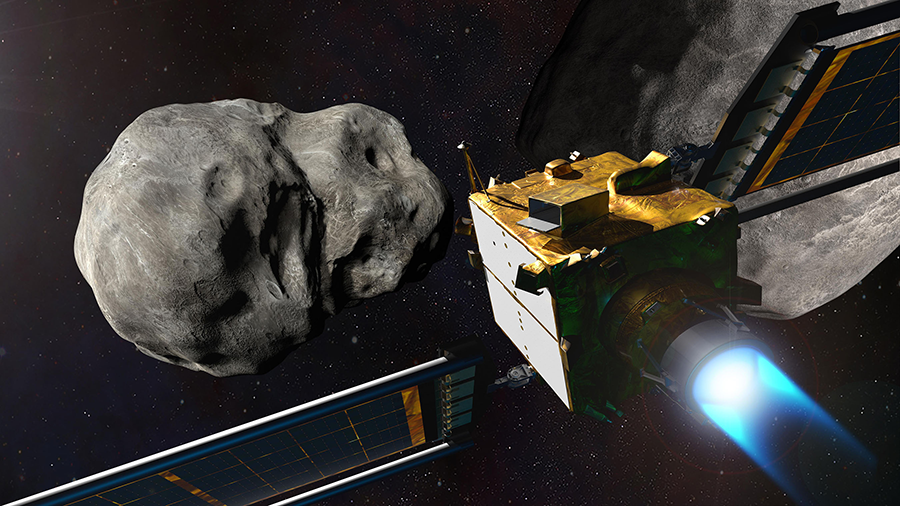

In 2016, NASA established a Planetary Defense Coordination Office, charged with leading the development of capabilities to anticipate and respond to potential asteroid perils. Several candidate technologies have been pursued, and one, the kinetic interceptor, has been operationally tested. This concept entails launching a physical mass to ram into the targeted asteroid at high speed, nudging it off its trajectory or shattering the asteroid as a last resort, much as a missile defense interceptor might attempt to do to a hostile attacker much closer to Earth.

In 2021-2022, NASA undertook the Double Asteroid Redirection Test mission, propelling a small spacecraft 11 million kilometers into the 160-meter-wide asteroid Dimorphos, which poses no threat to Earth. The program was a marvelous success, validating the ability of the craft’s autonomous guidance system to direct it unerringly to the impact point at 22,000 kilometers per hour. The asteroid’s original trajectory was indeed altered appreciably, even more than most prior calculations had anticipated.9

Nevertheless, the kinetic impactor concept has important limitations. It could succeed only against a relatively small target, a few hundred meters in size at most, and only if there was plenty of advance warning so that the small variance in the asteroid’s path could accumulate over time, causing the asteroid to miss Earth. Moreover, the scenario requires that the asteroid be a relatively solid, intact body rather than a mass of space rubble loosely held together by gravity, as some asteroids are. Additionally, the target asteroid could not be too fragile lest the impact shatter it rather than displace its course through space.

Other potential planetary defense concepts have been hypothesized and sketched out, but none has proceeded into testable hardware. One notion, the gravity tractor, would send a spacecraft to intercept an asteroid, but instead of crashing into it, the spacecraft would adopt a closely parallel flight path. As the microgravity between the two objects pulled them closer together, the spacecraft would incrementally power away, and the continuing gravity would bend the asteroid to follow, bit by bit departing from its original trajectory.10

Other even less-developed concepts would seek to install some type of engine on the asteroid or to paint it to alter the natural color and light reflectivity of one surface on the asteroid so it would differentially absorb solar energy as it spins, which could translate into slowly changing its course.

If the threatening asteroid was large, however, and if the available time frame was compressed, a more powerful response could be necessary. The attention of scientists and other experts therefore inevitably has been drawn to nuclear explosions, which offer the most efficient mechanism for transferring a large amount of energy to a distant target and represent a relatively mature technology, having been operationally tested 2,056 times, including several times in space.11

There has never been anything like a test nuclear explosion against a celestial body, but scientists have begun to contemplate some plausible methodologies. The current leading concept would not undertake to fracture the asteroid, despite several Hollywood movies luridly featuring that scenario. Doing that would probably leave most of the asteroid’s mass, which after the explosion would be highly radioactive, on a trajectory to collide with Earth. Moreover, fracturing the asteroid could create several distinct impact points on Earth, which would be comparable to a nuclear weapon with multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles and might expand the area of damage on the planet, inflicting even more harm than a single, larger crash.

Instead, a nuclear planetary defense mission likely would rely on a detonation at some short standoff distance from the asteroid and would employ the nuclear energy to vaporize volatile material on the surface of the asteroid. As those molecules rapidly evaporate or sublimate away, the resulting vapor would exert a tiny equal and opposite force, nudging the asteroid off track. Again, nothing of this sort has ever been tested, and there are no plans to undertake such an experiment.

Two relatively new international entities have emerged to study and respond to the asteroid threat. The Space Mission Planning Advisory Group is a collection of leading national space agencies, with an ambitious collective agenda to share information about asteroid exploratory missions and to collaborate to evaluate and recommend possible responses to asteroid scenarios.12 The companion International Asteroid Warning Network is an affinity group for dozens of astronomers and observatories to identify and characterize the population of potential asteroid and comet impact dangers and to serve as a clearinghouse for sharing their findings with the broader community.13

Legal Impediments

Any consideration of using nuclear detonations in space immediately inspires profound political and legal opposition.14 Three treaties or groups of treaties are implicated, each of which was created long ago for reasons having nothing to do with potential asteroid impacts. The treaties have enjoyed wide adherence and are recognized as foundational to terrestrial peace and security, but they nonetheless pose significant challenges for any nuclear planetary defense scheme.

First, under the 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty, each party legally undertakes “to prohibit, to prevent, and not to carry out any nuclear weapon test explosion, or any other nuclear explosion, at any place under its jurisdiction or control…in the atmosphere [and] beyond its limits, including outer space.” This constitutes a direct, categorical prohibition against the contemplated nuclear planetary defense mission.

The 1996 Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty would reinforce the 1963 treaty and extend a comparable proscription to any environment, including underground, as well as in space. Although this treaty has been signed and ratified by 178 countries, it is not in force because several required countries, including the United States, have not ratified it. Its signatories are nonetheless obligated by customary international law, as reflected in Article 18 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, “to refrain from acts which would defeat the object and purpose” of the treaty. In 2016 the UN Security Council authoritatively proclaimed that any nuclear explosion by any state would constitute such a defeat and therefore is already prohibited.15

Notably, these test ban treaties apply to nuclear weapons tests and to “any other nuclear explosion.” This explicit language ensures that even if a nuclear planetary defense operation might be characterized as a so-called peaceful nuclear explosion or “nuclear explosion for peaceful purposes,” there is no escape hatch from the legal prohibition.

Second, the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, the foundational instrument regulating human space activities, imposes the obligation “not to place in orbit around the Earth any objects carrying nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction, install such weapons on celestial bodies, or station such weapons in outer space in any other manner.”

Second, the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, the foundational instrument regulating human space activities, imposes the obligation “not to place in orbit around the Earth any objects carrying nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction, install such weapons on celestial bodies, or station such weapons in outer space in any other manner.”

Although this treaty is sometimes cited as a comprehensive “no nukes in space” commitment, its actual coverage is narrower. It proscribes only three specified activities regarding nuclear weapons: their placement in Earth orbit, installation on a celestial body, and stationing in space. Notably, the treaty does not bar the transit of a nuclear weapon through space. Although the key terms are not defined in the treaty or in the subsequent practice by states interpreting the language, it might be possible for a nuclear planetary defense mission to adopt an operational profile that dodged these constraints. For example, the nuclear explosive device might not have to orbit the Earth even once before being directed toward its target; it might not have to be installed on the asteroid if it were detonated at a distance; and its flight plan might not be regarded as having it stationed in space.

In addition, the Outer Space Treaty language applies to nuclear weapons, and some might seek to characterize a nuclear explosive device being employed for a peaceful, planet-saving operation as not constituting a weapon. That term might be reserved most appropriately for instruments used for a hostile, warlike, or criminal purpose. Of course, many items are dual use; a knife would be regarded as a weapon if it is wielded to threaten or stab someone but not when it is used to slice an apple. The literature on this point reflects an unresolved international debate regarding the treaty’s applicability to a nuclear planetary defense mission.

Finally, the several treaties dealing with nuclear nonproliferation also could be implicated, especially if the nuclear planetary defense mission were undertaken by a coalition of countries that included some legally authorized to possess nuclear weapons and some not. The 1968 nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), for example, prohibits parties that possess nuclear weapons from transferring to others a nuclear weapon or other nuclear explosive device or control over such a weapon, and it reciprocally prohibits non-nuclear-weapon states from receiving such a weapon or device or control over it. So, the respective roles of the various states collectively participating in a nuclear planetary defense mission would have to be precisely defined, to prohibit control passing to an unauthorized state.

Many regional treaties establishing nuclear-weapon-free zones go a significant step further in pursuit of nonproliferation, requiring their parties, in the language of the treaty applicable to Latin America, to “refrain from engaging in, encouraging or authorizing, directly or indirectly, or in any way participating in the testing, use, manufacture, production, possession, or control of any nuclear weapon.” This broad mandate would seem not only to bar a non-nuclear-weapon state from actively joining in a nuclear planetary defense mission, but also from requesting that other states undertake such a rescue or expressing political support for it. Although a nuclear planetary defense mission would have to be led by one or a handful of technologically advanced countries, it surely would be beneficial to develop a broad global consensus endorsing such an operation even if that required circumventing this legal restriction.

A similar effect could result from the ambitious scope of the 2021 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which comprehensively bars its states-parties from possessing, testing, using, or conducting other operations regarding nuclear weapons and includes an undertaking never to “assist, encourage or induce, in any way, anyone to engage in any activity prohibited to a State Party under this Treaty.” That mandate also could inhibit any effort to generate international support for or participation in a multinational nuclear planetary defense operation.

Additionally, any future international agreement that comprehensively sought a global, permanent abolition of nuclear weapons would be challenged by the asteroid scenario. Already, opponents of the concept of creating a world free of nuclear weapons cite the possible planetary defense application as a rationale against progress toward zero.

The Search for a Solution

What should be done if a threatening asteroid appears on the horizon and the potential array of non-nuclear planetary defense options seems inadequate to the task? Is there any way to maintain international fidelity to the treaties and collective adherence to the rule of law while acting efficaciously to protect the planet?

One potential recourse would be to alter relevant treaty obligations. Each of these agreements can be amended; each is also subject to withdrawal if a party’s “supreme interests” are jeopardized. These mechanisms are somewhat cumbersome, however, and can be time-consuming; in some instances, effective amendment requires a supermajority or even unanimity among the parties. Such changes also would constitute a permanent alteration in the treaty legal obligations rather than just a temporary exception. There are also valid excuses for nonperformance of international legal obligations, known as “circumstances that preclude the wrongfulness” of the state’s action, such as duress, necessity, and fundamentally changed circumstances. Again, none of these recognized rationales seems quite applicable to the situation under consideration here.16

Another alternative, favored by an ad hoc international lawyers working group established in 2017 by NASA and the space agencies of other cooperating countries, would turn to the UN Security Council.17 Under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, the Security Council possesses an extraordinary power in the event of a declared “threat to the peace” to create new law, including the even more extraordinary power effectively to supersede the obligations of prior treaties. The council could exercise that power to authorize a particular state or combination of states to undertake a nuclear planetary defense mission, notwithstanding the preexisting obligations of the Limited Test Ban Treaty, the Outer Space Treaty, the NPT, and other instruments noted above.

In so doing, the Security Council could immunize the acting states from any adverse legal consequences that would otherwise flow from their intentional, material departure from the implicated treaties. Once sufficient facts were known, the council could tightly restrict the authority it was delegating to certain states, limiting the number and type of nuclear weapons to be used and the way in which they would be applied, the identities of the states that could be involved in the most delicate parts of the operation, the time frame, the transparency of the operation, and other parameters.

Of course, the Security Council could adopt such a resolution only pursuant to unanimity or abstention among its five veto-wielding permanent members (China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States). If those powers cannot see eye to eye regarding this peril, then the planet truly would be jeopardized.

Other international institutions could play a supporting role in legitimizing a nuclear planetary defense mission. The UN General Assembly and its subordinate Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, as well as the Conference on Disarmament, do not possess the inherent lawmaking powers of the Security Council. Even so, a robust debate and endorsement by those bodies could manifest a high degree of global consensus on the appropriate course of action, helping politically to excuse what could otherwise constitute material breaches of legal obligations.

The danger of a catastrophic asteroid impact has only begun to attract the type and scale of attention and resources it demands. The problem requires technical finesse and large, sustained expenditures; it is grounded in a probabilistic assessment of potential hazards rather than a finite certainty; and it exposes a time frame that stretches far beyond any politician’s term of office—all factors that create a sure formula for shoving the issue to a back burner.

The use of a nuclear weapon would not be anyone’s first choice for a planetary defense mission. The financial costs and environmental consequences would be severe, the international politics could be corrosive, the legal jeopardy to important arms control treaties would be substantial, and the breaching of a decades-long taboo against nuclear weapons use would be dreadful.

Still, this option belongs on the list of possible responses, should the worst imaginable scenario emerge. Even the most substantial international legal commitments should never pose an obstacle to action that would be truly necessary to protect the planet from Armageddon, especially when there are mechanisms that could allow the world to stave off an incoming asteroid while demonstrating fidelity to the law.

ENDNOTES

1. Center for Near Earth Object Studies (CNEOS), NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, “Frequently Asked Questions,” n.d., https://cneos.jpl.nasa.gov/faq/ (accessed December 16, 2023).

2. NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, “Asteroid Watch,” n.d., https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/asteroid-watch (accessed December 16, 2023).

3. NASA, “Near-Earth Asteroids as of November 2023,” November 2023, https://science.nasa.gov/science-research/planetary-science/planetary-defense/near-earth-asteroids/.

4. ChicxulubCrater.org, “About the Chicxulub Crater,” n.d., http://www.chicxulubcrater.org/ (accessed December 16, 2023).

5. Natalia A. Artemieva and Valery V. Shuvalov, “From Tunguska to Chelyabinsk via Jupiter,” Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Vol. 44 (2016), p. 37, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-060115-012218.

6. Don Yeomans and Paul Chodas, “Additional Details on the Large Fireball Event Over Russia on Feb. 15, 2013,” Center for Near Earth Object Studies, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, March 1, 2013, https://cneos.jpl.nasa.gov/news/fireball_130301.html.

7. NASA, “Apophis,” n.d., https://science.nasa.gov/solar-system/asteroids/apophis/ (accessed December 16, 2023).

8. CNEOS, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, “Torino Impact Hazard Scale,” n.d., https://cneos.jpl.nasa.gov/sentry/torino_scale.html (accessed December 16, 2023).

9. Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, “Double Asteroid Redirection Test,” n.d., https://dart.jhuapl.edu/ (accessed December 16, 2023).

10. Committee to Review Near-Earth-Object Surveys and Hazard Mitigation Strategies Space Studies Board, “Defending Planet Earth: Near-Earth-Object Surveys and Hazard Mitigation Strategies,” National Research Council, 2010, pp. 66-88.

11. Arms Control Association, “Nuclear Testing Tally,” August 2023, https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/nucleartesttally.

12. European Space Agency, “Space Mission Planning Advisory Group,” n.d., https://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/smpag (accessed December 16, 2023).

13. See International Asteroid Warning Network (website), December 4, 2023, https://iawn.net/.

14. See Lt. Col. John C. Kunich, “Planetary Defense: The Legality of Global Survival,” Air Force Law Review, Vol. 41 (1997), p. 119; Jan Osburg et al., “Nuclear Devices for Planetary Defense,” n.d., https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20205008370/downloads/Nuclear_Devices_for_Planetary_Defense_ASCEND_2020

_FINAL_2020-10-02.pdf; Bryce G. Poole, “Against the Nuclear Option: Planetary Defence Under International Space Law,” Air & Space Law, Vol. 45, No. 1 (March 1, 2020): 55.

15. On September 15, 2016, the permanent members of the UN Security Council (China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States) collectively declared that a nuclear test by any country would defeat the object and purpose of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. Office of the Spokesperson, U.S. Department of State, “Joint Statement on the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty by the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty Nuclear-Weapon States,” September 15, 2016, https://2009-2017.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2016/09/261993.htm. This determination was subsequently endorsed by the full Security Council in Resolution 2310. UN Security Council, S/RES/2310, September 23, 2016.

16. “Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 2001,” Vol. II, Pt. 2, A/CN.4/SER.A/2001/Add.1 (Part 2), 2007, pp. 71-86.

17. Space Mission Planning Advisory Group (SMPAG) Ad-Hoc Working Group on Legal Issues, “Planetary Defence Legal Overview and Assessment,” SMPAG-RP-004, April 8, 2020, https://www.cosmos.esa.int/documents/336356/336472/SMPAG-RP-004_1_0_SMPAG_legal_report_2020-04-08+%281%29.pdf/60df8a3a-b081-4533-6008-5b6da5ee2a98?t

=1586443949723. See also David A. Koplow, “Exoatmospheric Plowshares: Using a Nuclear Explosive Device for Planetary Defense Against an Incoming Asteroid,” UCLA Journal of International Law and Foreign Affairs, Vol. 23, No. 1 (Spring 2019): 76.

David A. Koplow is Scott K. Ginsberg Professor of Law at the Georgetown University Law Center, where he teaches and writes in the areas of international law and national security law. He is a member of an ad hoc legal working group established by NASA and other national space agencies to advise on the legal aspects of planetary defense.

After creating the atomic bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer looked for an arms control solution to prevent an unwinnable superpower nuclear arms race.

April 2024

By David Goldfischer

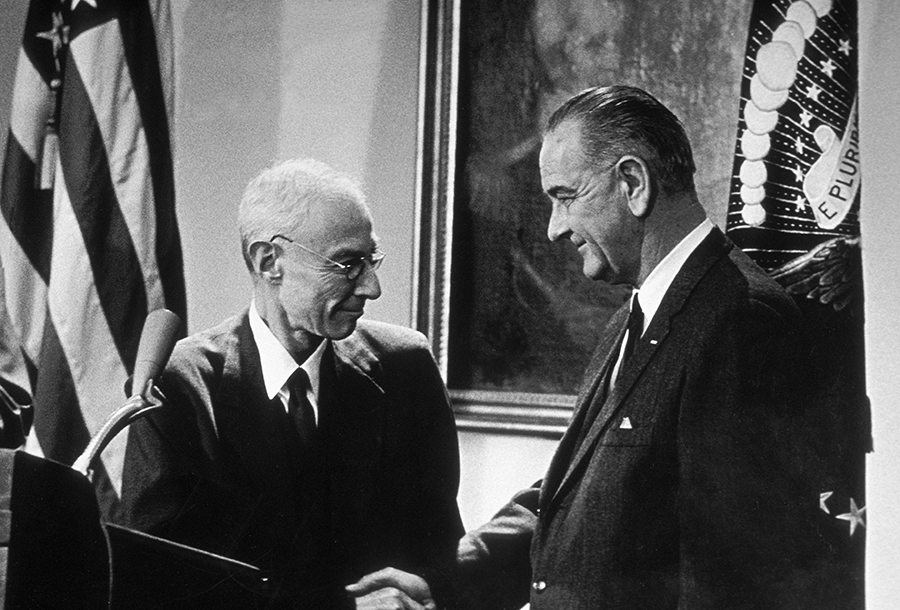

Christopher Nolan’s film Oppenheimer has educated a vast audience about a critical moment in world history. It also takes its viewers to a dark place, in which J. Robert Oppenheimer is punished for his effort to avert a nuclear arms race when he is stripped of his security clearance. As the movie expresses his thoughts, he had started then failed to stop “a chain reaction that might destroy the entire world.”

That might leave some viewers wondering how Oppenheimer hoped to prevent what he accurately foresaw as an unwinnable superpower nuclear arms race. Despite the personal struggles portrayed in the movie, he worked ceaselessly toward identifying a practical path toward that goal. Unfortunately, the answer he ultimately found has been all but forgotten.

That might leave some viewers wondering how Oppenheimer hoped to prevent what he accurately foresaw as an unwinnable superpower nuclear arms race. Despite the personal struggles portrayed in the movie, he worked ceaselessly toward identifying a practical path toward that goal. Unfortunately, the answer he ultimately found has been all but forgotten.

His initial hope was for comprehensive international control of everything from uranium mining to deployed weapons. As reflected in his work on the 1946 Acheson-Lilienthal report, that approach was overtaken by the deepening Cold War and the 1949 Soviet atomic bomb test.1

In that new context, Oppenheimer turned to a search for a nuclear policy that could contain the Soviet threat while avoiding capabilities for “exterminating civilian populations.” That phrase is from a majority report in 1949, which he authored, of the General Advisory Committee of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission.2 In it, he distinguished between atomic weapons sufficient for deterring attack and the development of a hydrogen bomb, whose almost limitless explosive power and “the global effects of its radioactivity,” would vastly magnify the nuclear danger. The committee’s call to suspend hydrogen bomb development while supporting work on low-yield tactical nuclear weapons reflected Oppenheimer’s emerging vision of minimally sufficient nuclear deterrence. Consistent with that approach and further antagonizing supporters of a nuclear airpower buildup, Oppenheimer participated in the military’s 1951 Project Vista, which argued that Europe could be defended with short-range tactical nuclear weapons rather than long-range strategic bombers.3

He next moved to consider whether efforts at population defense could contribute to the combined goals of deterring attack while avoiding civilian “extermination.” From the perspective of the U.S. Air Force leadership, his answer provided final proof of Oppenheimer’s treacherous “pattern of activities.”4 For those who shared his view that a nuclear arms race risked world destruction, however, his emerging policy approach represented a radical advance in how to reduce the nuclear danger. The “father of the atom bomb” was about to create the first coherent vision of superpower nuclear arms control.

A New Proposal

Oppenheimer’s new proposal, to put it simply, was for a superpower agreement that would avoid a buildup of bombs and bombers and instead direct Soviet and U.S. efforts toward defending their populations against nuclear attack. One might describe this approach as “mutual defense emphasis.”

It is understandable that his call for this arms control concept was left out of the film as peripheral to the high drama of its protagonist’s life and times. Yet, it also was ignored in the biography by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, on which the movie largely was based, and has received scant attention in most other histories of the nuclear age.

Because all scholars now agree that Oppenheimer’s banishment as an adviser on nuclear policy was unjust, it is worth examining whether the arms control concept that contributed to his downfall warrants reconsideration. That requires a look back at 1952, when Oppenheimer followed his work on Project Vista by joining a 1952 summer study at the MIT Lincoln Laboratory, which assessed prospects for defending the U.S. homeland against nuclear-armed bombers.5

The study concluded that a full-scale continental defense could intercept 60 to 80 percent of enemy bombers and that technological advances promised far greater effectiveness. Based on those findings, Oppenheimer concluded that although defense against a Soviet “knockout blow” technically was achievable, it would require that the Soviets decide to limit their own buildup of nuclear-capable long-range bombers. Although formal agreements were unlikely in that Cold War climate, Oppenheimer envisioned a tacit understanding in which the superpowers would couple low levels of bombers with large-scale efforts at detection and interception. In that case, he concluded, deterrence could be based on mutual fears that few if any bombers would reach their targets.

At the time, the Soviet Union was focused on constructing a multitiered radar network and thousands of jet interceptors, while deploying no nuclear-capable intercontinental-range bombers, essentially the reverse of the initial U.S. reliance on a purely offensive strategy. Oppenheimer expressed the hope that, in return for being spared a buildup of U.S. nuclear airpower that was certain to overwhelm even the massive Russian defensive effort, Moscow might be prepared to make deep cuts in its conventional forces threatening Western Europe. Only such bilateral concessions could avert the threats that each side feared most.

Oppenheimer then took this logic a step further. Should the day arrive when improved superpower relations revived interest in nuclear disarmament, he proposed that nationwide defenses would be a vital supplement to a verification regime. Although verification alone could not eliminate fears of hidden nuclear weapons and bombers, extensive defensive deployments could resolve that formidable obstacle to comprehensive offensive disarmament. As he explained in a 1953 article, a combination of robust verification measures and large-scale defenses could make “steps of evasion far too vast to conceal or far too small to have, in view of existing measures of defense, a decisive strategic effect.”6

That article became famous for its appeal to the American people for candor regarding the impending Soviet capability to destroy the nation’s “heart and life” even if the United States attacked first. In a nonpublic forum, Oppenheimer expressed hope that such candor would galvanize public support for a major effort to build a continental defense and negotiate a bilateral limit on offenses. Informed U.S. citizens, as a later advocate of this approach put it, would “prefer live Americans to dead Russians.”7

These ideas had been developed in meetings of the Oppenheimer-led Panel of Consultants on Disarmament during the waning months of the Truman administration. Its work included a stillborn “no first test” proposal for the hydrogen bomb, based on the argument that stopping at the brink of testing would prevent both sides from developing deliverable weapons while enabling a rapid response if one side broke the agreement.8 The first U.S. nuclear test occurred while the panel was still deliberating.

The panel’s report was delivered to newly elected President Dwight Eisenhower, who then heard direct appeals from panel members Oppenheimer, CIA Director Allen Dulles, and leading U.S. science adviser Vannevar Bush.9 Discussions within the administration embraced their call for a continental defense system while rejecting their accurate prediction that homeland defense would prove futile without an agreement to limit offensive forces. A year later, Dulles’ older brother, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, would announce the U.S. doctrine of “massive retaliation,” justifying the unfolding buildup to around 3,000 nuclear-armed bombers by the end of the 1950s.

A Bitter Attack

Oppenheimer’s case for mutual defense emphasis came under bitter attack by Air Force leadership, which regarded support for U.S. nuclear superiority as a litmus test of patriotism. A sample of the prevalent conspiratorial thinking was the testimony of the chief Air Force scientist, David Griggs, during the hearings that led to the revocation of Oppenheimer’s security clearance. “It was…told me by people who were approached to join the summer study that in order to achieve world peace…it was necessary not only to strengthen the air defense of the continental United States, but also to give up something, and the thing that was recommended that we give up was the…strategic part of our total air power,” Griggs said.10

It is largely forgotten that the original vision of nuclear arms control was based on restricting the offense to make strategic defense possible. In 1957 the arrival of the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), demonstrated by the Soviet launch of Sputnik, would make that arms control approach appear foredoomed, and U.S. arms control supporters soon seized on a moment when shooting down ballistic missiles was literally impossible. In a radical shift from Oppenheimer’s arms control vision, these arms control supporters reasoned that the best outcome would be a superpower agreement to deploy ICBMs in large but equal numbers and protect them from nuclear attack by placing them underground in hardened concrete silos. Because neither side could hope to eliminate the other’s nuclear-armed missiles by striking first, the prospect of devastating retaliation against the aggressor’s population would freeze both sides in a state of stable mutual deterrence. The goal of arms control had shifted from the pursuit of offensive nuclear disarmament to the preservation of peace through an enduring “balance of terror.”

By the time the two sides developed plausibly effective defenses against missiles during the 1960s, this logic called for banning their deployment, and the United States proposed such a plan for “offense only” mutual deterrence to the Soviet Union in 1967. When Soviet leaders objected, arguing that it would be better to ban offenses and allow population defenses, the United States responded that it would simply overwhelm any Soviet anti-ballistic missile defensive system by expanding its ICBM force.

In 1972 the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty enshrined the principle of assured vulnerability to a nuclear holocaust, which has guided U.S.-Russian strategic arms control from then through the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START). This approach soon became known as mutual assured destruction, a label created by Donald G. Brennan, who was also a supporter of mutual defense emphasis. He believed that the acronym MAD captured the insanity of entrusting safety to an arrangement based on forever avoiding accidental launches, miscalculation during a crisis, or a leader’s descent into insanity.

Oppenheimer’s defensive alternative to MAD had a remarkable if brief resurrection three decades later. President Ronald Reagan, facing widespread opposition to his 1983 call for a massive U.S. population defense known as the Strategic Defense Initiative, recast it from a nuclear victory strategy to a disarmament concept. Paul Nitze, Reagan’s senior arms control adviser, attended meetings of Oppenheimer’s 1952 disarmament panel as head of the Department of State’s policy planning staff. Now, as the Cold War waned, he embraced its call for a defense-protected disarmament regime, and Reagan approved his updated version of Oppenheimer’s arms control concept.

Presented to the Soviet arms control delegation in Geneva in January 1985, Nitze’s proposal called for a 10-year negotiated transition combining non-nuclear population defenses with complete offensive disarmament. His explanation of the need for nationwide defenses as a hedge against cheating verged on a verbatim repetition of Oppenheimer’s logic years earlier.

Nitze’s proposal initially was rejected by Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, who scoffed at Reagan’s vague promise to share U.S. missile defense technology. Yet, the Cold War had reached a turning point, and Gorbachev soon called for “a change in the entire pattern of armed forces” toward “imparting an exclusively defensive character to them.” In October 1991, weeks before his fall from power, Gorbachev announced that the Soviets were ready “to consider proposals…on non-nuclear anti-ballistic missile defenses.” The chain from Oppenheimer to Nitze to Gorbachev would extend to the first two leaders of the Russian successor state.

Back to the Past

On February 1, 1992, Russian President Boris Yeltsin called for a global missile defense system that would enable countries to slash or eliminate their nuclear arsenals.11 If that proposal reflected the giddy idealism of a new era, including reliance on a non-existent space-based missile shield, the United States by then had lost any interest in exploring cooperative defenses with the weak Soviet successor state. Eight years later, in May 2001, U.S. President George W. Bush would stun new Russian President Vladimir Putin by withdrawing from the ABM Treaty, signaling a prospective U.S. ballistic missile defense buildup that a still floundering Russia would be unable to match.

Looking back at that moment in 2019, Putin’s views on that U.S. decision are worth quoting:

[I]f the US side…wanted to withdraw from the [t]reaty…I suggested working jointly on missile-defence projects that should have involved the United States, Russia and Europe. … Those were absolutely specific proposals. I am convinced that the world would be a different place today, had our US partners accepted this proposal. Unfortunately, this did not happen. We can see that the situation is developing in another direction; new weapons and cutting-edge military technology are coming to the fore. Well, this is not our choice.12

The world now finds itself confronted with the same basic problem that confronted Oppenheimer in the early 1950s, in which hopes for comprehensive arms control have yielded to major-power confrontation, including a race to incorporate destabilizing new weapons technologies. The United States, Russia, and China are pursuing improved offensive systems and defenses against aircraft and missiles of all types and ranges. Distinctions between offensive and defensive weapons and forces, crucial to all forms of arms control, are subordinated to whatever cost-effective blend of capabilities best advances war-fighting strategies. New START, already suspended in part over the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, will expire in 2026; and as China approaches nuclear parity with the original superpowers, MAD offers no formula for three-way assured-destruction force levels.

The world continues to live with Oppenheimer’s forecast that harnessing the destructive power of nuclear weapons will enable powerful nuclear states to overwhelm any adversary’s unilateral efforts to limit wartime damage. It also lives with his realistic fear that human survival cannot be entrusted permanently to what he called the “strange stability” of the resulting balance of terror.

Oppenheimer’s original arms control concept proved too idealistic for his time and place and may well be equally so today. From the perspective of all that has happened since, however, directing diplomacy toward achieving mutual defense emphasis may be less quixotic than current hopes to sustain the view that mutual assured vulnerability to annihilation is the best of all possible nuclear worlds. If the world manages to outlast the new cold war as it somehow survived the first, the door should not be closed to reconsidering, as Oppenheimer was the first to propose, that population defenses and offensive disarmament may be “necessary complements.”

ENDNOTES

1. Chester A. Barnard et al., “A Report on the International Control of Atomic Energy,” U.S. Department of State Publication 2498, March 16, 1946, https://scarc.library.oregonstate.edu/omeka/exhibits/show/atomic/item/1236.

2. Atomicarchive.com, “General Advisory Committee’s Majority and Minority Reports on Building the H-Bomb,” n.d., https://www.atomicarchive.com/resources/documents/hydrogen/gac-report.html (accessed March 27, 2024).

3. David C. Elliot, “Project Vista and Nuclear Weapons in Europe,” International Security, Vol. 11, No. 1 (1986): 163-183.

4. U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer: Transcript of Hearings Before Personal Security Board and Texts of Principal Documents and Letters (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1970), p. 749.

5. Director’s Office, MIT Lincoln Laboratory, “The Soviet Atomic Threat, Oppenheimer, and the Need for National Air Defense,” The Bulletin, October 23, 2023, https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/153173/2023-10-20-Bulletin-The%20Soviet%20Atomic%20Threat%2c%20Oppenheimer%2c%20and%20the%20Need%20for%20National%20Air%20Defense.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.