This page-turner book is a timely reminder that 12,000 years of civilization could be reduced to rubble in mere minutes and hours.

June 2024

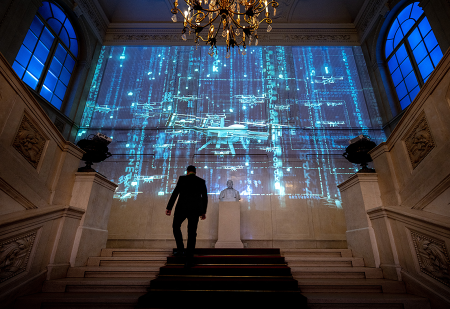

When the World Ends in 72 Minutes

Nuclear War: A Scenario

By Annie Jacobsen

Dutton, 2024

Reviewed by Tom Z. Collina

Annie Jacobsen’s Nuclear War: A Scenario is a page-turning thriller about how, step by tragic step, the world as we know it might end with nuclear weapons. It is a welcome and timely reminder that “12,000 years of civilization” could be “reduced to rubble in mere minutes and hours,” as the author puts it. In her realistic narrative, it is all over in 72 minutes.

The book runs the reader through an engagingly written, painstakingly detailed scenario in which North Korea launches a “bolt from the blue” nuclear attack against Washington, D.C. and Diablo Canyon Power Plant in central California. The United States responds with a much larger retaliation, involving 82 warheads, against North Korea. Because the U.S. intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) overfly Russia on their way to Pyongyang, Moscow thinks it is under attack from the United States and retaliates with 1,000 warheads. Before North Korea is destroyed, it detonates an electromagnetic pulse weapon over the United States. Finally, the United States retaliates with everything it has against Russia. Game over.

The bulk of the book is a riveting minute-by-minute account of how each step of this dizzying process plays out, starting with the launch of one warhead from North Korea. The launch is detected, analyzed, and assessed. At 3 minutes and 15 seconds after launch, the U.S. president is informed. At 9 minutes, an attempt is made to intercept the missile. It fails. At 23 minutes, after the first detonation in California, the U.S. president orders a strike against Pyongyang. At 33 minutes, the Pentagon is destroyed. At 41 minutes, Russia detects a massive nuclear attack heading its way. The dozens of expert interviews and deep research that Jacobsen conducted make the scenario feel realistic and terrifying. Along the way, the author reminds readers about some of the more troubling aspects of current nuclear policy, such as the facts that the United States or North Korea could start a world-ending nuclear war on the orders of just one person, a concept known as sole authority; that Russian and U.S. nuclear weapons are on high alert, ready to be launched at a moment’s notice, even before a reported attack has been confirmed to be real, a concept known as launch on warning; that U.S. ICBMs are highly vulnerable to attack and that their use against a nation such as North Korea would look like an attack against Russia; or that existing U.S. missile defenses stand little chance of stopping even a limited attack from North Korea.

In laying out this scenario, Jacobsen also challenges many of the questionable assertions employed by the nuclear establishment to defend the status quo. One of those assertions is that deterrence works. Well, it does until it does not. It is true that nuclear deterrence has worked so far and rational leaders seem to understand that initiating a nuclear attack against another state with nuclear weapons would be suicidal. Unfortunately, that does not mean it will keep working forever, and there are multiple ways it can fail catastrophically. As in Jacobsen’s narrative, a leader in a nuclear state such as North Korea can become irrational (a “mad king”) and launch a first strike for any reason at all. This may be a highly unlikely scenario, and some may say it is a thin reed on which to hang a whole book. Yet, that may be Jacobsen’s point: deterrence is vulnerable to factors that are out of our control.

Another questionable assertion is that a “limited” nuclear war would stay limited. Some would like everyone to believe that it is possible to have a “small” nuclear war, using just a few nuclear weapons, and that this could somehow restore deterrence before things really get ugly. Jacobsen shows just how dangerous such thinking can be. The gruesome logic of the system is biased toward quick and massive retaliation (“use them or lose them”), so limited use rapidly escalates into full-scale war even if no one intended that to happen. In the book, the United States never intends to start a nuclear war with Russia, but that is exactly what happens.

The author also makes it brutally clear that nuclear war has no winners and, as Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev predicted, “the survivors will envy the dead.” Her description of what would happen to Washington after getting hit with a 1-megaton bomb is particularly chilling. “Wind rips the skin off people’s faces and tears away limbs. Survivors die of shock, heart attack, blood loss. Errant power lines whip through the air, electrocuting people and setting new fires alight everywhere,” she writes. “Never in the history of mankind have so many human beings been killed so fast.” Capitol Hill is obliterated. The animals in the National Zoo have no chance. Globally, over time as smoke blocks out the sun, billions die. Humans have gone the way of the dinosaurs.

Jacobsen writes that, “[f]or as long as nuclear war exists as a possibility, it threatens mankind with Apocalypse. The survival of the human species hangs in the balance.” She concludes that rather than the United States, Russia, China, or North Korea, “[i]t was the nuclear weapons that were the enemy of us all. All along.”

What Now

Jacobsen revealed in Mother Jones that she “wrote this book to demonstrate—in appalling, minute-by-minute detail—just how horrifying a nuclear war would be. Join the conversation. While we can all still have one.”1 Yet, the book offers no solutions. The author has said that she did not want to step out of her “lane as a journalist and as a storyteller” and into the lane of an expert on policy fixes.

Even so, a key part of this much needed conversation is to ask what now. How can the world prevent a nuclear war that Jacobsen accurately describes as possible and catastrophic? For those who read this compelling book and are rightly motivated to get involved, what policies would prevent the very scenario she lays out?

In general, people on both sides of this debate think that nuclear war would have no winners and should be prevented. Those who support maintaining current nuclear arsenal levels, or even increasing them, justify their position on the need to have a strong nuclear force to deter an attack by others. Humanity must face the reality that even if the United States offered to eliminate its arsenal if others did so too, the others might not follow. Russia, in particular, appears to have little interest in reducing its arsenal and recently has made thinly veiled nuclear threats against Ukraine.

This creates a challenging environment for the most straightforward approach to ending the threat of nuclear war: eliminating nuclear weapons. The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons is the best vehicle for this approach. It has been in force since January 2021 and has been signed by more than 90 nations. Unfortunately, none of the nuclear-armed states currently support this treaty or seems likely to do so anytime soon.

Short of global elimination of nuclear weapons, the next best approach is gradual reductions. Alas, Russia has told the Biden administration that it is not interested in discussing ways to replace the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), which expires in early 2026. If New START disappears without being replaced, there would be no legal limits on Russian and U.S. nuclear forces for the first time in 50 years. China, for its part, is increasing its nuclear forces and also is not interested in talking about reductions, although Beijing recently said it is willing to discuss an agreement to prevent the first use of nuclear weapons. As long as the Biden administration remains committed to arms control, there is reason to keep pursuing diplomacy with China and Russia, but the near-term prospects for significant arms reductions are bleak.

If arsenal reductions are not promising now, there are changes in U.S. policy that could make nuclear war less likely. One policy ripe for change is sole authority. In the book, North Korea starts a nuclear war all by itself. Presumably, the leader of that nation has the absolute authority to make this decision. Washington likely cannot change Pyongyang’s launch policy or convince it to give up its nuclear arsenal, although it should try. The United States has a sole-authority policy as well, and North Korea has no monopoly on making bad decisions. Washington could at least reduce the risk of a U.S.-initiated nuclear war by requiring that any decision to launch a first strike must be a joint decision with Congress or a subset of its members. The initiation of nuclear war should require the shared authority of the executive and legislative branches. This seems like a prudent approach, particularly in light of the upcoming U.S. presidential election.

Another potential change involves launch on warning. This policy supports the president launching U.S. nuclear weapons after a possible attack has been detected by early-warning sensors but before the reported attack is proven to be real, such as by landing on U.S. soil. In the book, the U.S. president launches nuclear weapons only after the attack on California is confirmed, so this is not an example of launch on warning. Yet, the way the fictional president is rushed into a decision, with another attack reportedly heading toward Washington, is similar. Imagine an alternative scenario where the president is first removed from Washington to a remote location where he can take time to reach a decision when more information arrives. There is no need for the president to launch quickly, within minutes. In the book, a quick launch leads to a tragic error: sending a large force of U.S. ICBMs on a flight path over Russia.

A main reason why U.S. presidents are pushed by advisers to act quickly in a scenario such as this is that the country’s ICBMs are in fixed locations and thus are vulnerable to attack. If not used quickly, they may be destroyed by the incoming attack. This leads to rushed decisions. By contrast, U.S. nuclear-armed submarines at sea are not vulnerable to surprise attack and create no pressure for quick launch. Moreover, submarine-based weapons do not have to be launched from fixed sites; unlike ICBMs, they could attack North Korea without flying over Russia. The United States would have fared far better in Jacobsen’s scenario with no ICBMs at all, and such weapons should be retired. Short of retiring its ICBMs, Washington could prohibit their use in any mission that overflies a nuclear-armed state that is not the intended target.

Some critics say that Jacobsen’s scenario is not realistic, that U.S. planners would not launch ICBMs over Russia and would instead use submarines to avoid this possibility. Yet, that may be Jacobsen’s precise point. Humans make bad decisions all the time, especially in a crisis.

As a journalist, Jacobsen’s strength is her powerful storytelling, and readers can excuse her lack of solutions, some debatable aspects of the scenario, and even a few errant facts. Nuclear War is an excellent book for anyone who wants to understand just how quickly nuclear conflict can start and how badly it can end. With its gripping narrative and timely arrival, it has the potential to start a new debate on how best to avert nuclear war. This book is a welcome addition to global efforts to reduce the risk of the ultimate disaster.

ENDNOTE

1. Annie Jacobsen, “America’s Nuclear War Plan in the 1960’s Was Utter Madness. It Still Is,” Mother Jones, March 27, 2024, https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2024/03/nuclear-war-scenario-book-siop-weapons-annie-jacobsen/.

Tom Z. Collina, former senior policy adviser at Ploughshares Fund, is a nuclear expert and co-author of The Button: The New Nuclear Arms Race and Presidential Power From Truman to Trump.

Germany and Nuclear Weapons in the 21st Century: Atomic Zeitenwende?

Arms Control at a Crossroads: Renewal or Demise?

June 2024

Germany and Nuclear Weapons in the 21st Century: Atomic Zeitenwende?

Ulrich Kühn, ed.

Routledge

2024

The contributors to this collection have produced a valuable introduction to current nuclear debates in Germany, providing foreign readers with a first reference for deciphering recurring allusions to an independent nuclear deterrent in German political circles. Although not a comprehensive history of postwar Germany’s relationship to the bomb, this edited volume provides the context to understand a wide range of contemporary nuclear issues. The volume benefits from an impressive range of viewpoints, with highlights such as Giorgio Franceschini’s chapter explaining shifts in the Green Party’s policy on nuclear weapons and Michal Onderco’s polling of German public opinion.

Editor Ulrich Kühn and co-author Barbara Kunz explain in their chapter that a Franco-German route to a German nuclear weapon is barred by a “lack of strategic convergence” and numerous practical, legal, doctrinal, and cultural challenges. In examining Germany’s decision to give up its own latent potential, Kühn argues that the strategic considerations that led to the abandonment of nuclear technology persist to this day. The book makes clear that stray talk in the Bundestag distracts from the far more substantial and nuanced nuclear debate in Germany on the country’s role in nonproliferation, NATO deterrence, and disarmament.—XIAODON LIANG

Arms Control at a Crossroads: Renewal or Demise?

Jeffrey A. Larsen and Shane Smith, eds.

Lynne Rienner Publishers

2024

With the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty expiring in 2026 and the future of arms control uncertain, this edited volume centers on the editors’ assertion that arms control is “not quite” dead and its value as a tool of statecraft remains even if it faces steep challenges ahead. The book presents 16 analyses by respected experts who probe the editors’ view that “arms control will need to adapt to the realities of a new era to remain a relevant instrument of statecraft.” It provides a comprehensive overview of international efforts to rein in nuclear weapons.

The book covers a wide variety of arms control and cooperative security topics, including the theory and contexts of arms control, the perspectives of major powers and their competitive relationships, and the future of arms control in traditional and new domains, such as cyberspace and outer space.

In a world that has grown pessimistic about containing nuclear weapons, the editors acknowledge that arms control has “lost its luster among many of the world’s political leaders.” Yet, they remain hopeful that “political leaders will one day again see the utility and value of arms control as a primary tool for managing competition.”

—SHIZUKA KURAMITSU

China has not provided a “substantive response” to U.S. strategic risk-reduction proposals but other bilateral engagement continues.

June 2024

By Xiaodon Liang and Shizuka Kuramitsu

China has not provided a “substantive response” to three U.S. strategic risk-reduction proposals and has declined to schedule a follow-on meeting to a November 2023 bilateral meeting on arms control and nonproliferation matters, U.S. officials said.

But diplomatic engagement continues on other tracks. Chinese and U.S. delegations met in Geneva on May 14 to begin a dialogue on strategic risks associated with artificial intelligence (AI). U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin spoke with his counterpart, Chinese Defense Minister Adm. Dong Jun, for the first time in 18 months on May 31 on the sidelines of the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore. U.S. officials confirmed that nuclear weapons concerns were on the agenda.

According to U.S. officials, the United States at the November meeting proposed risk reduction measures on missile launch notifications, a crisis hotline, and space deconfliction. China “has declined a follow-on meeting and has not provided a substantive response to the risk reduction suggestions we put forward,” Bonnie Jenkins, U.S. undersecretary of state for arms control and international security, testified May 15 before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Jenkins said that the United States would continue to “increase diplomatic pressure” on China to be more transparent about its nuclear forces. Citing the Defense Department estimate that China will increase the number of its operational warheads from 500 warheads currently to 1,000 by 2030, she said the buildup raised questions about China’s nuclear posture and strategic goals.

The United States also has urged China and Russia to mirror the unilateral U.S. statement that humans, rather than AI, always should be in control of nuclear weapons. Speaking to reporters May 2, Paul Dean, principal deputy assistant secretary of state at the Bureau of Arms Control, Deterrence, and Stability, described that commitment as “an extremely important norm of responsible behavior.”

But when asked by reporters on May 13, a U.S. spokesperson declined to confirm that nuclear command and control would be prioritized during the talks with China in Geneva. According to a summary of the talks issued May 15 by the U.S. National Security Council, the two sides discussed “respective approaches to AI safety and risk management,” and the United States raised concerns about Chinese “misuse” of AI. The Associated Press on May 15 described hints of tension between the parties and said that the Chinese delegation criticized U.S. restrictions on exports of computer hardware that are critical to research in the AI field.

Meanwhile, China has continued to reaffirm its nuclear no-first-use policy. Arriving in France for a state visit May 5, Chinese President Xi Jinping, writing in the French newspaper Le Figaro, “stressed that nuclear weapons must not be used, and a nuclear war must not be fought.”

In response to questions from Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.), Jenkins said she was aware of a specific Chinese no-first-use proposal but the matter would have to be taken up by the interagency process. Jenkins added that she had questions about how China’s no-first-use policy was compatible with its current nuclear weapons buildup.

Jenkins also said that, in bilateral discussions with China, the United States stressed the importance of being a responsible nuclear power and how Russian threats of nuclear use are irresponsible.

Xi “has played an important role in de-escalating Russia’s irresponsible nuclear threats, and I am confident that [he] will continue to do so,” European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said in a May 6 press statement, following talks with Xi and French President Emmanuel Macron.

On a May 16 state visit to China, Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed with Xi to deepen the “comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for the new era” as they commemorated this year’s 75th anniversary of Chinese-Russian diplomatic relations, according to reports from the Chinese Foreign Ministry.

The pressure built after Israel launched a bombardment of Rafah on May 26.

June 2024

By Carol Giacomo

U.S. President Joe Biden came under fresh pressure to halt the transfer of weapons to Israel after the state launched a deadly bombardment of Rafah that killed at least 45 people.

On May 28, CNN reported that its analysis of videos and a review by explosive experts showed that U.S.-made munitions were used in the Rafah attack, which occurred May 26, two days after the International Court of Justice ordered Israel to “immediately” halt its military offensive in the southern Gaza city.

Earlier in the month, Biden threatened to suspend the delivery of some U.S.-made offensive weapons if Israeli forces entered population centers in Rafah, a refuge for civilians fleeing the fighting that is also viewed as a Hamas stronghold. U.S. laws and a U.S. presidential directive impose requirements on presidents to curb U.S. weapons transfers to countries that violate international humanitarian law or fail to avoid harming civilians.

But even after Israeli strikes killed what the Gazan Health Ministry said were dozens of people sheltering in tent camps and wounded 249 more, the White House suggested that the military offensive still had not crossed a redline that would force significant changes in U.S. support for Israel.

On May 28, National Security Council spokesman John Kirby said that what the Biden administration does not want to see in Rafah is a “major ground operation” in which “thousands and thousands of troops [are] moving in a maneuvered, concentrated, coordinated way against a variety of targets on the ground.”

He said that type of operation was not happening, and “I have no policy changes to speak of,” although he called the deaths in Rafah “devastating.”

For months, the Biden administration has straddled the sensitive question of whether Israel has violated U.S. and international humanitarian law as it sought to punish Hamas for the extremist group’s brutal Oct. 7 attack that killed more than 1,200 Israelis and foreign nationals.

One particular deadly attack occurred on April 1 when seven employees of World Central Kitchen, an aid group, were killed by Israeli airstrikes. The Israeli military took responsibility for the catastrophe, The New York Times reported on April 8, and said it presumed some of World Central Kitchen’s vehicles were carrying militants, raising new questions about Israel’s ability to identify and protect civilians.

On May 10, the Biden administration announced the results of its internal review of Israel’s use of U.S.-provided weapons in the war in Gaza, as called for in National Security Memorandum-20. (See ACT, March 2024.)

The report said that “it is reasonable to assess” that U.S. weapons have been used in violation of humanitarian law and that Israel has acted in ways that blocked U.S. humanitarian assistance. But it does not make a specific enough finding to trigger sanctions against Israel.

The report also found that the U.S. intelligence community “assesses that Israel could do more to avoid civilian harm.”

U.S. law, regulation, and the Conventional Arms Transfer Policy require the United States to withhold military assistance when U.S. weapons are used in contravention of international humanitarian law.

Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.), who authored a proposed legislative amendment that prompted the drafting of the national security memorandum, said the report “ducks the ultimate questions that [it] was designed to determine,” according to AI Monitor.

The issue has divided the State Department, where some officials urged Secretary of State Antony Blinken to conclude that Israel has violated the terms of the memorandum and others pressed him to certify that it did not.

In early May, the Biden administration paused the delivery of a shipment of 3,500 500- and 2,000-pound bombs to Israel, Axios reported May 5, but other weapons continue to flow.

The United States provides more weapons to Israel than any other country, including $80 billion last year. Since Oct. 7, these transfers have included bombs, artillery shells, precision guidance kits, guided missiles, drones, and ammunition.

Israel’s Rafah operation has spawned international outrage and a demand for an end to the fighting, including from leaders in the European Union, the United Nations, Egypt, and China. The chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court has requested arrest warrants for Israel’s prime minister and defense minister, and the Biden administration has expressed concern about the lack of a clear Israeli plan for postwar Gaza.

A U.S. Republican senator seemed to suggest that Israel should consider using nuclear weapons to defeat Hamas in Gaza, drawing criticism for normalizing talk of a taboo option.

June 2024

By Libby Flatoff and Shizuka Kuramitsu

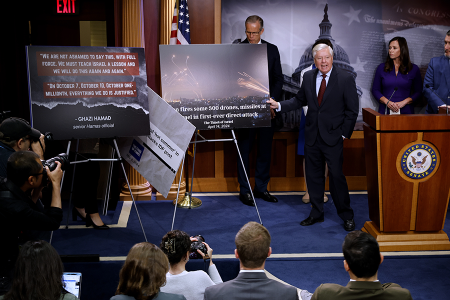

A senior U.S. Republican senator appeared to suggest that Israel should consider using nuclear weapons to defeat Hamas in Gaza, drawing criticism from arms control activists and others for normalizing talk of an option that the world has long considered anathema.

During a May 8 hearing at which he faulted the Biden administration for halting the delivery of some weapons to Israel, Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) demanded of top U.S. defense officials, “Would you have supported dropping bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II?…Do you think that was disproportionate?”

“You’re going to tell (Israel) how to fight the war when everybody around them wants to kill all the Jews? Give Israel what they need to fight the war. This is Hiroshima and Nagasaki on steroids,” Graham told Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Gen. Charles Brown at a Senate Appropriations subcommittee hearing.

Four days later on NBC, Graham again justified the use of nuclear weapons on Nagasaki and Hiroshima because the weapons were used “to end a war we [could not] afford to lose” and insisted, “Give Israel the bombs they need to end the war they can’t afford to lose.”

Whether Graham actually was advocating the first nuclear weapons use since World War II or not, the comments landed with a thud in Tokyo where Japanese Foreign Minister Yoko Kamikawa described the remarks as “not appropriate” at a May 10 press conference.

She said that Japan “has been expressing for a long time…[that] the use of nuclear weapons does not match the spirit of humanitarianism, which is the ideological foundation of international law, because of their tremendous destructive and lethal power.”

She added that Japan had reiterated this point to U.S. officials.

On May 14, Kamikawa addressed the issue again, telling reporters that “[i]t was very regrettable that such remarks have been made repeatedly.”

The Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations, also called Nihon Hidankyo, sent a letter to the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo requesting a retraction of Graham’s remarks, NHK reported on May 15. “The remarks go against international humanitarian law…. [N]ow that the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons has come into effect, the remarks can only be described as an anachronistic and malicious delusion,” the letter said.

In addition, the mayors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in separate press conferences on May 16, condemned Graham’s justification of atomic bombings on their cities, according to Jiji Press.

Graham’s comments “run counter to the direction we should be taking in the future toward our ideals [of a nuclear-free world],” which U.S. President Joe Biden reaffirmed in Hiroshima at the 2023 Group of Seven meeting, Kazumi Matsui, the mayor of Hiroshima, said. (See ACT, June 2023.) “With humanitarian and catastrophic consequences brought about by atomic weapons in mind, nothing can justify the use of nuclear weapons,” Shiro Suzuki, the mayor of Nagasaki, said.

Meanwhile, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, wrote on social media May 13 that “likening the situation in Gaza to Hiroshima and Nagasaki [is] utterly unacceptable” and Graham’s statements “shouldn’t be normalized.”

Graham’s remarks garnered the most attention, but other U.S. politicians expressed similar views. Appearing on Newsmax on May 14, Rep. Greg Murphy (R-N.C.) also invoked Hiroshima and Nagasaki and said, “[T]his is where Israel has every single right in the world to press this conflict further.”

Rep. Tim Walberg (R-Mich.) was caught on video at a town hall meeting on March 25 suggesting that the United States should use a nuclear bomb on Gaza to “get it over quick…. [Gaza] should be like Nagasaki and Hiroshima.”

Walberg later denied that he was calling for the use of nuclear weapons, claiming instead that he “used a metaphor to convey the need for both Israel and Ukraine to win their wars as swiftly as possible, without putting American troops in harm’s way.” But Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.), the first Palestinian-American member of Congress, criticized Walberg, saying he “is not the first member of Congress to use despicable, violent, dehumanizing language to describe their genocidal intent in Gaza and will not be the last.”

Despite Israel’s long-standing refusal to acknowledge having a nuclear weapons program, Israeli Heritage Minister Amichai Eliyafu said on Radio Kol Barama that using nuclear weapons in Gaza was “one of the possibilities,” the Times of Israel reported on Nov. 5.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu denied this possibility and suspended Eliyafu, but Eliyafu in January again “urged that Israel must find ways for Gazans that are more painful than death to defeat them and break their morale, as the [United States] did with Japan,” Middle East Monitor reported on Jan. 6.

Despite voicing strong support for regulating autonomous weapons, an international conference reached no conclusion on how that should be done.

June 2024

By Michael T. Klare

An international conference that drew more than 1,000 participants, including government officials from 144 nations, showed strong support for regulating autonomous weapons systems, but reached no conclusion on exactly how that should be done, organizers said.

There is a “strong convergence” that these systems “that cannot be used in accordance with international law or that are ethically unacceptable should be explicitly prohibited” and that all other autonomous weapons systems “should be appropriately regulated,” Austrian Foreign Minister Alexander Schallenberg, chair of the Vienna Conference on Autonomous Weapons Systems, said in his closing summary.

The April 29-30 conference, hosted by Austria, focused attention on the dangers posed by the unregulated deployment of these weapons systems, sometimes called “killer robots,” and on mobilizing support for negotiations leading to legally binding restrictions on such systems.

Schallenberg and other participants expressed concern that, without urgent action, these systems, which can orient themselves on the battlefield and employ lethal force with minimal human oversight, could soon be deployed worldwide, endangering the lives of noncombatants. The foreign minister spoke of a “ring of fire” from the Russian war on Ukraine to the Middle East to the Sahel region of Africa and warned that “technology is moving ahead with racing speed while politics is lagging behind.”

“This is the Oppenheimer moment of our generation,” Schallenberg said. “The preventative window for such action is closing.”

Over two days of plenaries and panels, speakers from academia, civil society, industry, and the diplomatic community addressed the dangers posed by autonomous weapons systems and various strategies for regulating them. Numerous experts warned that once untethered from human control, these systems could engage in unauthorized attacks on civilians or trigger unintended escalatory moves.

As reflected in public statements and panel discussions, there was near-universal agreement that, in the absence of persistent human control, the battlefield use of such systems is inconsistent with international law and human morality. But participants expressed some disagreements over the best way to regulate them.

The conference occurred at a watershed moment in the international drive to impose international controls on autonomous weapons systems. For the past 10 years, a UN group of governmental experts has been meeting under the auspices of the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) to identify the dangers posed by these devices and assess various proposals for regulating them, including a protocol to the CCW banning them altogether.

During these discussions, many participants in the group of experts coalesced around the so-called two-tiered approach, which would ban any lethal autonomous weapons systems that cannot be operated under persistent human control and would impose strict regulations on all other such weapons. But because the CCW operates by consensus, progress toward implementation of these proposals has been blocked by several countries, including Russia and the United States, that oppose legally binding restrictions on these systems.

This impasse has sparked two alternative approaches to their regulation. The advocates of a legally binding instrument, having lost patience with the group of experts, have urged the UN General Assembly to consider such a measure.

In December, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution expressing concern over the dangers posed by these systems and calling on the secretary-general to conduct a study of the topic in preparation for a General Assembly debate scheduled for the fall. (See ACT, December 2023.)

An alternative approach, favored by the United States, the United Kingdom, and several of their allies, calls for the adoption of voluntary constraints on the use of autonomous weapons systems. As affirmed in a document titled “Political Declaration on Responsible Military Use of Artificial Intelligence and Autonomy,” released by the U.S. State Department in November, there are legitimate battlefield uses for such systems as long as they are used in accordance with international law and “within a responsible human chain of command and control.” (See ACT, April 2024.)

Based on statements by panelists and government officials, most participants in the Vienna conference appeared to favor the first approach, abandoning the CCW and pursuing a legally binding instrument, preferably through the General Assembly.

“The process at the CCW is a dead end because of the rule of consensus and the possibility of certain states, like Russia, blocking any meaningful measures on autonomous weapons,” Anthony Aguirre, executive director of the U.S.-based Future of Life Institute, said. “I think we need a new treaty, and that treaty needs to be negotiated in the UN General Assembly.”

Most of the states represented at the conference, including Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Chile, Egypt, Germany, Mexico, Pakistan, Peru, New Zealand, South Africa, and Switzerland, echoed Aguirre’s view, asserting support for negotiations leading to such a treaty. But other states, including Australia, Canada, Italy, Japan, Turkey, the UK, and the United States, indicated that the CCW remains the most appropriate forum for further discussion of autonomous weapons systems regulation.

With the conference behind them, Schallenberg and his allies are looking to preserve the convergence of views that the conference achieved and ensure that it is brought to bear at the General Assembly in September.

Russia conducted military exercises involving nonstrategic nuclear weapons, framing the drills as a response to NATO’s support for Ukraine.

June 2024

By Xiaodon Liang

Russia conducted military exercises involving nonstrategic nuclear weapons in late May and framed the drills as a response to statements and actions by NATO in support of Ukraine. The invocation of nuclear options perpetuates a pattern of nuclear saber-rattling by Russia since the start of its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. (See ACT, September 2022.)

In a May 6 press release announcing the exercises, the Russian Foreign Ministry said the drills were intended to send a “sobering signal to the West.” Russia’s complaints include the delivery of French, UK, and U.S. strike missiles to Ukraine and the authorization of their use against targets in Russia. The Russian statement also referenced French President Emmanuel Macron’s May 2 interview with The Economist reaffirming that France has not ruled out sending its own troops to Ukraine.

Dmitry Medvedev, deputy chairman of the Russian security council, stated in a May 10 social media post that, under “certain circumstances,” the response to attacks against targets on Russian territories would not be limited to Ukraine and may involve “a special kind of arms.”

France and the United Kingdom have provided Ukraine with the Storm Shadow air-launched cruise missile, known in France as the SCALP-EG, for defense against the Russian invasion. The Russian statement describes the missile as a “long-range” weapon. Manufacturer MBDA lists a 250 kilometer range, but the UK Air Force claims the missile can operate out to 550 kilometers. These missiles first arrived in Ukraine last summer, but UK Foreign Minister David Cameron’s May 2 statement that the UK would not object to Ukraine using the missile against targets in Russia provoked the Russian response.

The Russian statement also criticized the United States for developing and producing ground-launched missile systems that would have been barred previously by the now-defunct Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty. The statement said that Russia would terminate its unilateral moratorium on the deployment of these systems if the United States were to deploy such missiles in Europe or the Asia-Pacific region. (See ACT, May 2024.) U.S. intelligence believes that Russia had already deployed a weapons system barred by the INF Treaty, the 9M729 cruise missile. (See ACT, June 2019.)

The United States has not transferred missile systems to Ukraine that would have fallen within INF Treaty restrictions, but it has provided Kyiv with the Army Tactical Missile System, a ballistic missile with an estimated range of 300 kilometers, the State Department said on April 24. The Russian statement also criticized this transfer. A Defense Department spokesperson on May 6 described the announcement of the nonstrategic nuclear exercises as “irresponsible rhetoric,” adding that there was no change observed in Russia’s strategic posture.

The Russian Defense Ministry announced the first phase of the exercise in a May 21 Telegram social media post and said it involved units equipped with the Iskander missile system assigned to the Southern Military District, as well as aircraft of the Russian Aerospace Forces bearing the Kinzhal hypersonic missile. No end date was mentioned.

According to the ministry, the exercises involved handling nuclear warheads and pairing them with missiles, as well as maneuvers by the missile launchers and aircraft. In a Telegram post May 6, the ministry said that naval vessels would participate.

Russia often includes nonstrategic nuclear weapons in regular, large-scale exercises, but does not publicize separate drills of nonstrategic missile units. The delivery vehicles operated by these units may include shorter-range tactical missiles with a range of up to 300 kilometers, as well as longer-range missiles.

Estimates of the total number of Russian nonstrategic nuclear weapons are imprecise, but U.S. intelligence and independent sources place the number between 1,000 and 2,000.

Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko confirmed on May 9 that his country’s military forces would take part in the nonstrategic nuclear weapons exercises, Tass reported. Days earlier, the Belarusian military had ordered snap inspections of units equipped with the Iskander missile system and the Su-25 combat aircraft.

Russian President Vladimir Putin announced in June 2022 that Russia would provide Belarusian forces with the nuclear-capable Iskander and configure Belarusian Su-25s for a nuclear role. In March 2023, he added that nuclear weapons would be stored in Belarus.

Open-source investigations conducted by independent analysts and The New York Times confirm progress in constructing a likely nuclear weapons storage site near Asipovichy, Belarus. In March, NATO officials, including Lithuanian Defense Minister Arvydas Anusauskas, told Foreign Policy that Russian nuclear forces had redeployed into Belarus.

The State Department imposed new sanctions on Russia for using choking and riot

control agents in violation of the international chemical weapons ban.

June 2024

By Mina Rozei

The United States has accused Russia of violating the international chemical weapons ban by using choking and riot control agents multiple times in its full-scale war against Ukraine and has imposed new sanctions as punishment.

In a May 1 statement, the U.S. State Department said that it had “made a determination…that Russia has used the chemical weapon chloropicrin against Ukrainian forces in violation of the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) [and]…has used riot control agents as a method of warfare in Ukraine, also in violation of the CWC.”

“The use of such chemicals is not an isolated incident and is probably driven by Russian forces’ desire to dislodge Ukrainian forces from fortified positions and achieve tactical gains on the battlefield,” the department added.

But on May 7, the Technical Secretariat of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), which oversees the CWC, released a statement saying that it had been “monitoring the situation on the territory of Ukraine since the start of the war in February 2022” and that despite allegations reported by Russia and Ukraine to the OPCW, the evidence of chemical weapons use remained “insufficiently substantiated.”

In its statement, the State Department said that, in coordination with the Treasury Department, it is sanctioning three governmental entities associated with Russia’s chemical and biological weapons programs and four Russian companies providing support to such entities. The entities include a Russian specialized military unit that the United States claims facilitated the use of chloropicrin against Ukrainian troops.

The Treasury Department is separately sanctioning three entities and two individuals involved in procuring items for military institutes involved in Russia’s chemical and biological weapons programs, pursuant to a separate weapons of mass destruction nonproliferation authority, the State Department said.

It also announced new sanctions against “more than 280 individuals and entities” connected to Russia’s energy, mining, and military sectors in an effort to stem “Russia’s ability to wage its war against Ukraine.”

On May 2, Russian spokesperson Dmitry Peskov denied the U.S. accusations, saying “Russia has been and remains committed to its obligations under international law in this area.”

This is not the first time there have been reports of Russia using riot control agents on the battlefield or chloropicrin in Ukraine. In February, the Ukrainian military published a statement claiming that Russia had been using chloropicrin throughout 2023. (See ACT, March 2024.) Russia has denied these allegations repeatedly, but the Ukrainian army has claimed that at least 500 soldiers have been treated for exposure to toxic substances, including one who died from suffocating on tear gas, according to Al Jazeera on May 2.

Chloropicrin, a choking agent that causes severe irritation to the eyes, skin, and lungs, was used in World War I and is listed under Schedule 3 of the CWC as a banned agent whose use constitutes chemical warfare.

The use of riot control agents is permitted in certain circumstances. They often are used by police forces worldwide to quell protests, but they are prohibited on the battlefield because soldiers confined to trenches without gas masks are forced either to flee dugouts and trenches under enemy fire or risk suffocation.

The OPCW cautioned that the situation in Ukraine “remains volatile and extremely concerning regarding the possible re-emergence of use of toxic chemicals as weapons.” This comes after the OPCW verified chemical weapons attacks in Syria by the Syrian government in 2013 and the Islamic State group in 2018, marking an uptick in the use of chemical agents in war after decades in which they were considered taboo.

In its statement, the OPCW noted that Russia continues to deny “making use of such weapons” and said that, in order for the OPCW "to conduct any activities pertaining to allegations of use of toxic chemicals as weapons,” CWC states-parties would have to make a formal request. “So far, the Secretariat has not received any such request for action” in Ukraine, the statement said.

The Ukrainian parliament on April 24 ratified an additional agreement on privileges and immunities for technical assistance visits between Ukraine and the OPCW secretariat. This action creates the legal basis for Ukraine to cooperate with OPCW technical assistance visits for analyzing samples of toxic chemical agents that may have been used by Russian forces in Ukraine.

The OPCW also said that it remains open to information from states-parties and will continue to support Ukraine under CWC Article X, which provides assistance and protection to a state-party that has been attacked or threatened with attacks by chemical weapons.

North Korea is continuing to test new military systems and build up its nuclear arsenal in response to U.S. and South Korean activities.

June 2024

By Kelsey Davenport

North Korea is continuing to test new military systems and pledging to build up its nuclear arsenal further in response to U.S. and South Korean activities.

On May 18, North Korea said it tested a new ballistic missile with an “autonomous navigation system.” The state-run Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) said the test verified the “accuracy and reliability” of the new navigation system.

On the same day, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un visited a military production facility and expressed “great satisfaction” with the work being done in “bolstering up” the “nuclear war deterrent of the country.” According to KCNA, he stressed the importance of accelerating certain production activities to further expand North Korea’s nuclear forces.

These new capabilities are driving South Korea to prepare to respond to large-scale aerial attacks from North Korea. Seoul held a drill focused on repelling North Korean projectiles, including ballistic missiles and cruise missiles. In a May 14 press release, South Korean Air Force Lt. Gen. Kim Hyung-soo said that recent conflicts overseas demonstrate that initial responses to “large-scale aerial provocations determine the success or failure of the war.”

North Korea continues to justify expanding its nuclear arsenal as necessary to respond to what it says are security dynamics and hostile U.S. policy toward Pyongyang. Pyongyang reiterated that it would expand its arsenal after Washington conducted a subcritical nuclear test in May.

In a May 20 report, KCNA described the U.S. test as a “dangerous act” and said Washington has “revealed” that its strategic goal is to “militarily control other countries with the unchallenged nuclear edge.”

The test has added “new tension” to the security situation on the Korean peninsula, the statement said. North Korea will not tolerate a “strategic imbalance” on the Korean peninsula and will reconsider its deterrence posture in response, the statement said.

In addition to showcasing new systems, North Korea conducted a military exercise designed to test the country’s preparedness for a nuclear counterattack.

According to KCNA, North Korea on April 22 tested its “nuclear trigger” command-and-control system for the first time. This system enables Pyongyang to switch rocket launchers from conventionally armed shells to nuclear armed shells. This capability “substantially” strengthens North Korea’s “prompt counterattack capacity.” The test also provided an opportunity to reexamine the “reliability of the system of command, management, control, and operation of the whole nuclear weapons forces.”

KCNA reported that rocket launchers used in the drill accurately struck their targets and that Kim expressed “great satisfaction” with the drill and noted that plans to build up the country’s nuclear forces have been “translated into reality.”

North Korea is compelled to “more overwhelmingly and more rapidly bolster up its strongest military muscle” in response to the “ceaseless military provocations” from “hostile forces,” KCNA said.

Specifically, the statement condemned recent South Korean-U.S. joint airborne exercises held in April, which KCNA described as “extremely provocative and aggressive.”

The United States continues to defend the necessity of joint military exercises. Daniel Kritenbrink, assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs, said on May 14 at the Brookings Institution that the United States has no choice but to “double down” on military cooperation with South Korea and Japan in response to North Korea’s military developments and rejection of U.S. calls for dialogue. He said U.S. cooperation with regional allies has “reached unprecedented levels” to counter the growing threat from North Korea.

Kritenbrink also referenced the importance of enforcing sanctions against North Korea, saying that the United States is left with “no choice but to focus on these harder elements of our strategy.”

As part of the U.S. sanctions strategy, Japan, South Korea, and the United States coordinated a joint statement endorsed by 50 states condemning Russia’s veto in the UN Security Council of a resolution that would have extended the panel of experts charged with assessing the implementation of UN sanctions on North Korea. (See ACT, May 2024.) The panel’s mandate officially ended April 30.

The statement said it is “imperative” for UN member states to comply with Security Council resolutions and that states “must now consider how to continue access to this kind of objective, independent analysis in order to address [North Korea’s] unlawful [weapons of mass destruction] and ballistic missile advancements.”

North Korea responded to the statement by saying that any efforts to reestablish a panel of experts is “bound to meet self-destruction with the passage of time.” In a May 5 statement, Kim Song, North Korea’s representative to the United Nations, said that the panel of experts and the UN sanctions regime is a “tool for the hegemonic policy” of the United States.

For the second consecutive time, the UN Security Council rejected a draft Russian resolution that called on countries to ban all weapons in space.

June 2024

By Shizuka Kuramitsu

For the second consecutive time, the UN Security Council rejected a draft Russian resolution that called on countries to ban all weapons in space, not just weapons of mass destruction.

The vote on May 20 was 7-7, with Switzerland abstaining. It was the same losing tally as when Russia, backed by China, first requested a vote on a similar resolution on April 24. The resolution requires nine votes for adoption.

The back-to-back votes reflect a political duel triggered in February by U.S. allegations that Russia is developing a space-based nuclear anti-satellite (ASAT) capability in violation of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which prohibits the deployment of “nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction” in space.

Since then, U.S. suspicions about Russian activities have deepened, prompting Mallory Stewart, U.S. assistant secretary of state, to warn on May 3 that the United States will continue using its “diplomatic tools” to raise this issue bilaterally, in the United Nations, and in other multilateral forums “until Russia provides credible assurances that they have ceased these efforts.”

In an effort to discourage the Russian program, Japan and the United States in April proposed a resolution reiterating support for the treaty. But that resolution failed when Russia used its veto to block the measure on April 24. The final vote was 13-1, with China abstaining. (See ACT, May 2024.)

During debate on the May 20 vote, Robert Wood, the U.S. deputy UN ambassador, dismissed the Russian draft resolution as “the culmination of Russia’s campaign of diplomatic gaslighting and dissembling.”

“[O]ver the past several weeks, and following widespread condemnation from a geographically diverse group of member states in the General Assembly…Russia has sought to distract from its dangerous efforts to put a nuclear weapon into orbit,” Wood said.

Russian UN Ambassador Vasily Nebenzia accused states that did not support the Russian draft of favoring “a free hand for the expedited militarization of outer space.”

He emphasized that the Russian draft intended to reaffirm “states’ commitments not to use space for the deployment of any forms of weapons, including weapons of mass destruction,” and said that this “is the language that our American colleagues had refused to include in the text…from the very beginning.”

Russia’s draft was co-sponsored by Belarus, China, Nicaragua, North Korea, and Syria.

Adrian Hauri, Switzerland’s deputy UN ambassador, said his country abstained because “the spirit of flexibility and a framework of trust were lacking” and its suggestions were not taken into consideration despite its support for several elements of the Russian draft.

In her May 3 comments at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Stewart said that the Russian satellite suspected of carrying components for a potential nuclear ASAT weapon is in “unusual” orbit in “a region of higher radiation than normal lower-earth orbits, but not high enough of a radiation environment to allow accelerated testing of electronics,” which is the scientific purpose of the satellite claimed by Russia.

On May 20, Wood said that another Russian capability, a counterspace weapon, was deployed “into the same orbit as a U.S. government satellite” and it “follows prior Russian satellite launches likely of counterspace systems to low earth orbit in 2019 and 2022.” Pentagon spokesperson Air Force Maj. Gen. Pat Ryder confirmed this assessment May 21 .

Russian officials continued to deny that the country has a new ASAT capability. Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov called the U.S. allegation “fake news” while Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said that Russia “act[s] absolutely in accordance with international law, we do not violate anything,” Tass reported on May 22.

Meanwhile, according to Pavel Podvig, a nuclear expert, and The Wall Street Journal, the satellite to which Stewart referred likely is the Cosmos-2553, which was launched Feb. 5, 2022. But Breaking Defense reported on May 22 that “as of yet…no official has publicly named Cosmos-2553 as the satellite in question.”