| Executive Summary · Report Overview · Resources · Country List | ||||

| GICNT Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism |

MTCR Missile Technology Control Regime |

PSI Proliferation Security Initiative |

NSG Nuclear Suppliers Group |

G7 Global Partnership |

The Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI) was launched in 2003 as a voluntary initiative designed to disrupt and interdict WMD-related materials, technologies, and means of delivery in transit. The United States led efforts to establish PSI, in part due to the 2002 U.S. National Strategy to Combat Weapons of Mass Destruction, which identified strengthening interdictions as an area of focus, and a failed attempt later that year to interdict North Korean scud missiles bound for Yemen on flagless ship.

The Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI) was launched in 2003 as a voluntary initiative designed to disrupt and interdict WMD-related materials, technologies, and means of delivery in transit. The United States led efforts to establish PSI, in part due to the 2002 U.S. National Strategy to Combat Weapons of Mass Destruction, which identified strengthening interdictions as an area of focus, and a failed attempt later that year to interdict North Korean scud missiles bound for Yemen on flagless ship.

The United States, along with ten like-minded countries, met several times in 2003 to craft PSI’s Statement of Principles. The final draft, released in September 2003, did not create law or a new organization. Rather, in ascribing to the Statement of Principles, participating states agree to use existing national laws and international authorities to undertake measures unilaterally or in cooperation with other states to interdict suspected proliferation transfers and streamline procedures for sharing information about potential proliferation related shipments with other states.

The PSI is primarily intended to encourage participating countries to take greater advantage of their own existing national laws to intercept threatening trade passing through territories where they have jurisdiction to act. It also focuses on implementation of existing international and domestic legal authorities. The PSI member states are also encouraged to expand their legal authority to interdict shipments by signing bilateral boarding agreements with select countries to secure expedited processes or pre-approval for stopping and searching their ships at sea. In addition to interdicting transfers of proliferation concern, the statement of principles commits states to strengthening national authorities to facilitate interdictions and exchanging information with other states regarding suspect shipments.

PSI members do not meet on a regular basis.The PSI held a high-level meeting at the 10th anniversary in 2013, and a mid-level political meeting in Washington, DC in January 2016. Outside of these events, the Operational Experts Group (OEG), which is comprised of 21 member states, meets periodically to plan exercises, discuss recent activities and interdictions, and share relevant information.

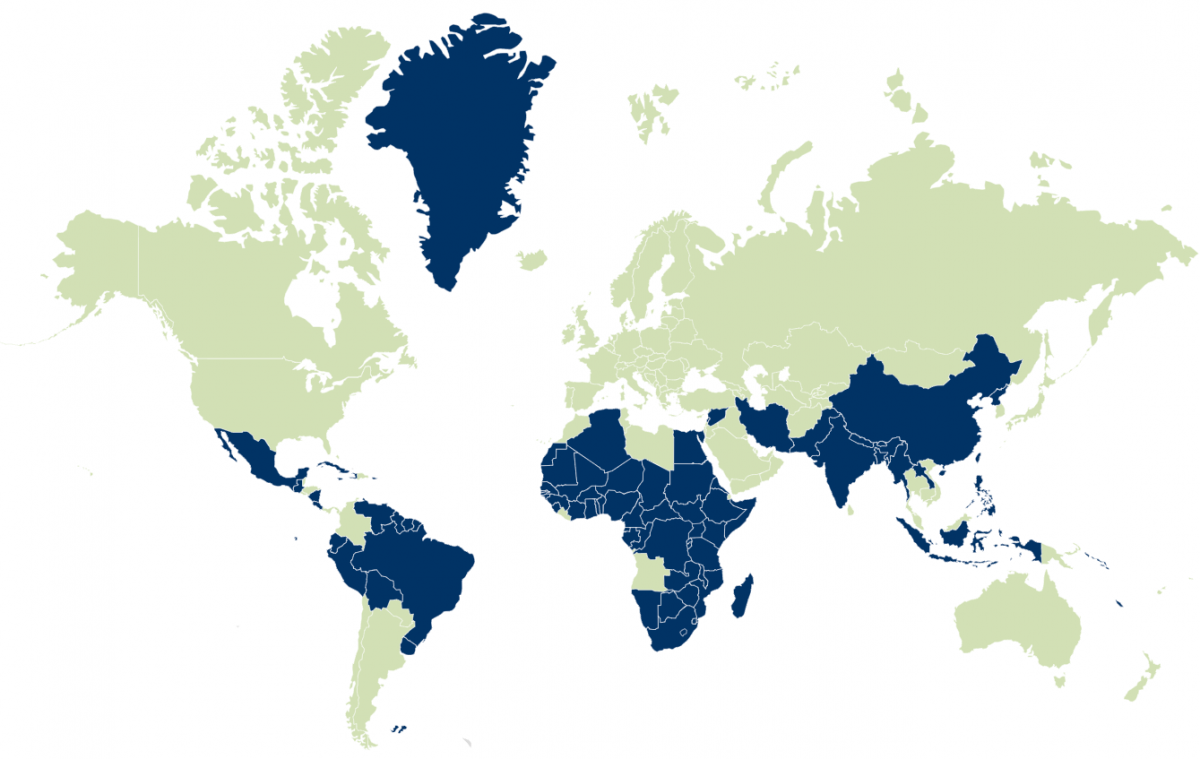

PSI has 105 subscribing states. Membership is open to any member state that endorses the principles. While PSI membership has expanded dramatically, exercises and activities are disproportionately hosted by the original 11 states. The United States, for instance, hosted 11 of the 40 exercises that took place during the first six years of the initiative.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Expand Membership: Key states remain outside of PSI. Several of these countries, such as China and Pakistan are known to have supplied technologies for WMD and/or ballistic missile programs in the past. Others key states outside of the regime such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Brazil, and South Africa, have important roles as regional leaders or in shipping. Targeting countries with flags of convenience, like Gibraltar, Comoros, and Bremuda, for membership in PSI would also be an important step forward in strengthening the regime.

- Strengthen National Authorities: States should be encouraged to ratify the 2005 protocol to the Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Maritime Navigation (SUA Convention), which allows ships to be boarded, with consent of the flag state, if they are suspected of carrying illicit cargo. Ratification strengthens the legal basis for interdictions, and only 33 countries have acted on 2005 protocol. PSI could encourage members with capacity to help states review and update national authorities to align with international standards.

- Prioritize Regional Exercises Based on Proliferation Trends: Proliferation risks and illicit trafficking routes vary regionally and by state. Looking toward regionally-focused workshops and exercises driven by a needs-based assessment of domestic capabilities can help target key areas of concern. In 2005, PSI participants began examining steps necessary to develop and share analyses of key proliferation actors, networks, and financing structures. Expanding these analyses from the state level to regional level could help inform exercises.

- Expand the OEG: Currently the 21-members that comprise the OEG are largely European and North American countries. Argentina is the only South American representative and there are no African countries in the group. Greater geographic diversity could contribute to a more regionally specific exercises and activities. Ratification of the SUA protocol could be a requirement for OEG membership, which would also reinforce and strengthen that convention.

- Enhance enforcement of and reporting on relevant treaties and obligations: PSI could require all participating countries to enforce relevant UN Security Council resolutions related to preventing WMD-proliferation, such as UNSCR 1540 and restrictions on North Korea. While, as members of the UN, these are binding obligations, a number of countries, including PSI member states, have not reported on implementation of relevant Security Council sanctions measures.

- Consider a UN Security Council Resolution on Interdictions: Originally the United States encouraged the inclusion of explicit interdiction authority in UN Security Council Resolution 1540 (2004). At that time some Security Council members opposed the inclusion of interdiction measures and it was eventually dropped. A separate resolution, with clear interdiction authorities, could combat concerns amongst states that are squeamish about the legality of interdictions under international law.

- Secure dedicated funding: In some countries, including the United States, PSI does not have dedicated funding in the budget to support its activities. Dedicated funding could help ensure continuity of activities and also provide reimbursement for states that detain and interdict vessels to ensure that the cost of compliance with PSI is not overly burdensome.