Negotiating With North Korea: An interview with former U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Stephen Biegun

June 2021

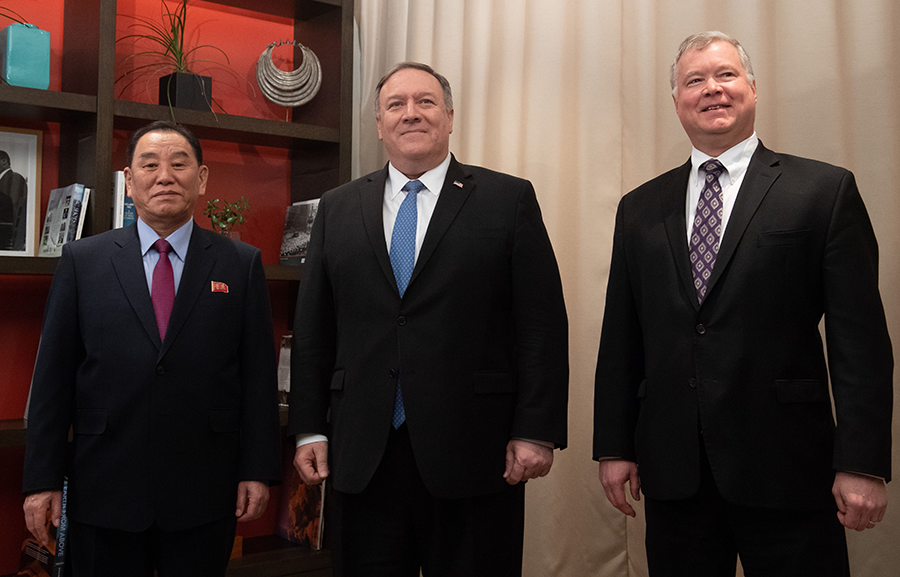

For more than two years, Stephen Biegun was U.S. deputy secretary of state and the top envoy executing President Donald Trump’s highly personal and ultimately unsuccessful diplomacy with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un. Biegun had eight meetings with North Korean officials and accompanied Trump in 2019 to meetings with Kim in Hanoi and also at the Demilitarized Zone. In his first interview since leaving government, Biegun discussed his views on what the last administration tried to accomplish and what went wrong and offered some advice to the Biden administration. The interview has been edited for space and clarity.

Arms Control Today: When Trump took office in 2017, the outgoing Obama administration warned that North Korea's nuclear program posed one of the most significant security threats. It remains so today. As the Biden administration prepares to adjust U.S. policy to deal with the North’s nuclear and missile arsenal, what advice would you offer?

Stephen Biegun: The administration has begun to roll out its recent policy review, and so we're starting to understand how they intend to proceed. During the transition between the two administrations, we did a very thorough, deep dive on a number of issues, but none more so than North Korea. As the former special representative for North Korea, I and my team sat down with President-elect Joe Biden's team to walk them through where we were and really to share almost every detail of our interactions with the North Koreans, certainly everything that was available to us. It looks to me like the Biden policy is largely a continuation of what the negotiating team in the [Trump] State Department was trying to attain from the North Koreans, which is an agreement on a path toward denuclearization with a certain endpoint that is complete denuclearization but that we can structure along the way with some flexibility. We wanted to move in parallel on other things that might help open the aperture for progress like people-to-people exchanges, greater transparency, and confidence building on the Korean peninsula. I think the Biden administration's conclusions are logical and, frankly, are the best among the choices that are available to any administration.

Stephen Biegun: The administration has begun to roll out its recent policy review, and so we're starting to understand how they intend to proceed. During the transition between the two administrations, we did a very thorough, deep dive on a number of issues, but none more so than North Korea. As the former special representative for North Korea, I and my team sat down with President-elect Joe Biden's team to walk them through where we were and really to share almost every detail of our interactions with the North Koreans, certainly everything that was available to us. It looks to me like the Biden policy is largely a continuation of what the negotiating team in the [Trump] State Department was trying to attain from the North Koreans, which is an agreement on a path toward denuclearization with a certain endpoint that is complete denuclearization but that we can structure along the way with some flexibility. We wanted to move in parallel on other things that might help open the aperture for progress like people-to-people exchanges, greater transparency, and confidence building on the Korean peninsula. I think the Biden administration's conclusions are logical and, frankly, are the best among the choices that are available to any administration.

That said, it's not significantly different than much of what's been tried in the past, and so it begs the question whether or not one can expect any different outcome. I think the key factor in whether or not the United States will make progress with North Korea rests with whether or not the North Korean government is prepared to go down this course. That's the challenge that we confronted in the Trump administration. We eventually came to the conclusion that the North Koreans simply weren't prepared to do what the two leaders had laid out. So I'd advise them to start with the establishment of communication, which I think they have been making some progress doing. Get a reliable channel for that communication going forward, so that we can have a more sustained set of diplomatic engagements.

ACT: In April, the U.S. intelligence community’s “Worldwide Threat Assessment” report concluded that "Kim Jong Un views nuclear weapons as the ultimate deterrent against foreign intervention and believes that over time he will gain international acceptance and respect as a nuclear power." Do you share this assessment?

Biegun: I think it's less important what the North Koreans think in this regard than what we in the rest of the world think. I would certainly never advocate accepting North Korea as a nuclear weapons state, and the Biden administration has been quite clear that they don't either. The implications of that are larger than the Korean peninsula. If North Korea were to essentially convince the world that it would never give up its nuclear weapons, fairly soon other countries will begin making decisions on their own security in relation to North Korea that could also involve the development of nuclear weapons. There are several countries in East Asia that could over a short period of time develop nuclear weapons.

So, I think it's incumbent upon us to retain our determination and clarity about the need to do away with these nuclear weapons.

That's not to say there aren’t other things we can do. If the Kim regime truly wanted to make the transition to a different relationship with the rest of the world, there are ways to address concerns about security that don't require nuclear weapons. The premise of a country needing nuclear weapons as a deterrent is that they are at risk of being invaded. I just find that to be an absurd proposition. There's no intention in South Korea and certainly no intention in the United States to act militarily against North Korea, so the whole premise frankly is absurd.

I actually don't think security is the driver of the North Korean nuclear weapons program. It’s national mobilization around the ideology of the regime. Also, I think the North Koreans know well, it's an attention getter. They used their weapons of mass destruction program to attract concessions from the outside world in the past. What we tried to do is show them is there is a better way through diplomacy.

ACT: Should the goals set out by Kim and Trump in their 2018 Singapore summit joint statement of working toward a "lasting and stable" peace regime and "complete denuclearization on the Korean peninsula" remain U.S. policy objectives?

Biegun: Absolutely, it should remain the policy objective. I would be surprised if you would find anybody who would suggest otherwise, even among the more hard-line voices on North Korea policy. The challenge has never been what our goal is. The challenge has been how to get there.

The Singapore joint statement offers a high-level agreement on where we're going. What we tried to do over the two and a half years that I was leading the efforts on behalf of the secretary of state and the president is translate those commitments into more detailed road maps that over time would get us to an agreed end state—normalization of relations, a permanent peace treaty on the Korean peninsula, the complete elimination of weapons of mass destruction on the Korean peninsula, even in later stages economic cooperation–and all this affected and tempered by broader societal contact, people-to-people exchanges, inter-Korean cooperation, and so on.

Trump had a sweeping vision for how to get there, and he was prepared to move as quickly as the North Koreans were prepared to move. But at the end of the day, the North Koreans get a vote. They were really stuck in an old form of thinking. They wanted to bicker and minimize their commitments and give up as little as possible and gain unilateral concessions. That wasn't going to happen.

The failure to reach an agreement in Hanoi underlined for them that this wasn't going to be a one-sided diplomacy. Had they moved, had they engaged, had they been willing to see where this can go, I think they could have changed history on the Korean peninsula, but I don't think they'd made a decision they wanted to do that. I don't know when we'll be able to queue up that alignment of opportunities again. I hope the Biden administration and their team are able to do so, but the short of it is, the North Koreans missed an opportunity.

ACT: Why do you think that was such a special moment?

Biegun: The North Koreans have long said in engagements with my predecessors on these issues that if the two leaders could agree, then anything was possible. It was almost something of a mantra from North Korean representatives over the years, and President Trump, in his own unconventional and often controversial way, put that to the test. The president had a lot of confidence in his own abilities. He was not constrained by critics over the conventions of the past. So, he proposed a summit in Singapore to sit down with Kim and basically say, hey, you know, this war ended 65 years ago, let's find a way to put it behind us.

For all the controversy and debate that his foreign policies generated, I can say as a negotiator that it was incredibly empowering to be able to test a proposition like that. For many of the president's critics, their concern was that somehow he was going to give away the store, that he was going to accept the one-sided deal. I think what the summit in Hanoi showed was that it was going to take two to tango.

We had high hopes going into the summit. I and our negotiating team were there a week before the summit. We'd been to Pyongyang a few weeks before that, and we met in Washington a few weeks before that. We had laid out to each other in detail what our views were, what our objectives were. They didn't align entirely, but each side knew what the other side was looking for out of this. When we got to Hanoi, our North Korean counterparts had absolutely no authority to discuss denuclearization issues, which is just absurd. It was one of the core points of agreement between the two leaders in Singapore.

ACT: Do you still think a negotiated settlement with North Korea is possible?

ACT: Do you still think a negotiated settlement with North Korea is possible?

Biegun: My belief in that is unshaken.

ACT: One apparent area of tension within the Trump administration was the pace and sequencing of denuclearization by North Korea, with some U.S. officials advocating a complete denuclearization within a very short time frame.

Biegun: Without a doubt, there were differing views among the staff in the administration. But elections are for presidents, not for the staff. The president's view was that he was prepared to reach an agreement provided that it successfully denuclearized North Korea. I think the speed with which that happened, were we to have gotten that agreement with the North Koreans, was negotiable.

Our hope was to move as quickly as possible, and we wanted to tie the benefits for North Korea to the speed with which North Korea wanted the lifting of sanctions. They controlled the tempo of that. The faster they met our expectations on denuclearization, the faster the sanctions went away. It was a fairly simple formula.

But we were also looking at denuclearization as just one line of effort across multiple lines of effort, including transforming relations on the Korean peninsula, economic collaboration, and potential diplomatic representation in each other's capitals. We saw that in parallel with creating a more secure Korean peninsula, with confidence-building measures and transparency through military exchanges, ultimately through the negotiation of a permanent treaty to end the Korean War.

Of course, denuclearization was going to be the toughest. The other thing that was non-negotiable from our point of view was that, regardless of the timing, two things had to happen. To begin, the North Koreans had to freeze everything. We weren't going to take everything out on day one, but they could stop. They could turn off the centrifuges. They could turn off the nuclear reactors. They could stop the production of weapons of mass destruction. The other non-negotiable was that the endpoint had to be complete denuclearization. The rest of it in between, plenty of room to negotiate how that happens.

ACT: Could that Trump-Kim summit-level approach have been adjusted in some way that would have made it more successful?

Biegun: What would have made it more successful is if the North Koreans engaged in meaningful, working-level negotiations in advance of the summits in order to produce more substantive agreements for our leaders. I have very good reason to believe that the North Koreans felt like they got exactly what they wanted, which was profile and prestige, without having made any commitments that were actionable. I think that may have lulled them into a mistaken view that that's all this was about, and in coming to Hanoi, that they could similarly do so. What they didn't realize was we were getting into a deeper level of discussion at that point.

Had the North Koreans been willing to discuss denuclearization with our negotiating team, had they brought appropriate experts to those discussions—we never saw a uniform or a scientist at these meetings. Our delegation was comprised of scientists from the Department of Energy, missile experts from the intelligence community. We had international law and sanctions experts. We had an interagency delegation that we brought to Pyongyang and Hanoi. The North Koreans simply failed to match the ambition.

The other thing I'd say about the president's diplomacy is that I saw absolutely no downside in it and, in some ways, it may even have created challenges for the North Koreans because their regime is being judged by itself and by its own people as to what they're able to achieve. If North Korea were to continue to seek that kind of engagement without delivering on the commitments that it makes or the commitments that it's expected to make, I think that it only worsens global opinion toward the North Korean regime.

One of the things that was always very effective for us is that we worked with partners and allies and even countries with whom we had more challenging relationships, like China and Russia. We were always willing to meet. We weren't putting any price on the North Koreans sitting down across the table.

ACT: You said the North Korean negotiating team wasn't empowered to discuss steps toward denuclearization in meetings with your team ahead of the Hanoi summit. Did that inhibit progress?

Biegun: Of course it did, because in the lead-up to the summit in Hanoi, the two teams spent nearly a week together trying to hammer out the basis for the two leaders to reach an agreement, a much more detailed set of documents than my predecessors had been able to obtain at the Singapore summit. To their credit, the North Koreans brought some creative ideas of their own on how we could improve people-to-people cooperation and transform relations on the Korean peninsula, but the key driver of the Singapore summit was denuclearization. Literally, the offer from North Korea was a “big present.” The negotiators said when Kim would arrive in Hanoi, he would have a big present for Trump, but we had to agree at the front to lift all the sanctions. I'm a practical person; tell me what your opening gambit is, tell me what your bottom line is, but don't tell me you're bringing me a big present.

ACT: They told you that without defining what the big present would be?

Biegun: Without any definition of what it would be.

The North Korean delegation came with ideas on everything but denuclearization. I think the play was that they thought that the president was desperate for a deal and they were going to save that for the leader-level meeting. Lo and behold, that proved to be a very mistaken strategy. Anyone who encouraged them to pursue that policy, whether it was internally or external voices, perhaps even in South Korea, it was a huge mistake.

But the president's meetings with Chairman Kim, even though the gap was too large for us to reach an agreement in Hanoi, were cordial and friendly. The president's last words to Kim in Hanoi were, “Let's keep at it, let's get something.” Another summit was not going to happen without substantial engagement by the North Koreans at the working level. Unfortunately, after Hanoi and then COVID in 2020 made it all but impossible, the level of engagement diminished significantly.

ACT: Why were there conflicting reports about what was put on the table in Hanoi? North Korean officials denied they offered partial denuclearization for a full lifting of sanctions. Instead, they said, Pyongyang requested a partial removal of UN sanctions in exchange for a permanent halt of nuclear and ballistic missile testing and the full verifiable dismantlement of facilities at Yongbyon.

Biegun: Yongbyon is only a portion of North Korea's nuclear weapons program. The North Korean rebuttal, which was delivered after the summit by Foreign Minister Ri Yong Ho and Vice Minister Choe Son Hui, was that they'd only asked for a partial lifting of sanctions. But we understood the value and the impact of every sanction that was in place, and what the North Koreans were asking for was a complete lifting of UN Security Council sanctions. In effect, the only remaining strictures on trade would be actively doing business with the weapons of mass destruction facilities and enterprises themselves. So in terms of what the North Koreans offered, any knowledgeable expert would recognize it was a partial denuclearization for a full lifting of sanctions, and there were no subsequent commitments. It would in effect accept North Korea as a nuclear weapons state. That was implicitly what was in that offer.

ACT: Some observers argue the lack of progress on denuclearization was due to the failure of the two sides to maintain a regular dialogue between high-level meetings. Do you agree?

Biegun: This takes us back to where we started and why I am so emphatic that establishing a reliable channel of communication is an essential antecedent to making progress. You can't have these episodic engagements. The North Koreans, as my predecessors can attest, use even the willingness to answer the phone or not answer the phone as a negotiating tactic and then oftentimes seek to extract a concession to answer the phone. There is a deeply ingrained tactic on the part of North Koreans that to show up for a meeting requires a concession.

During the two and a half years that I carried the North Korea portfolio, I met eight times with the North Koreans, and that wasn't enough. It was a lot. It was more than I think most people recognized, and not all the meetings were highly publicized, but it wasn't enough. We need that sustained engagement. I think the United States, whether under Trump or Biden or quite frankly any other president, would be committed to a process like that. But the North Koreans get a vote.

ACT: North Korea has become highly adept at sidestepping U.S. and UN sanctions and has been unwilling to make concessions in response to those sanctions. No doubt, some partners, namely China, could do more to enforce international sanctions now in place. Have we effectively reached the limits of using sanctions to coerce better behavior on nuclear matters from North Korea?

Biegun: Sanctions rarely if ever produce, in and of themselves, a policy shift. The sanctions are a necessary component of diplomacy that affects the choices or the timetable that the other party may have in terms of whatever it is you're seeking to address. So, sanctions are a tool, not the policy itself.

No amount of sanctions evasion is able to overcome the severe downward turn of the North Korean economy because the sanctions are draconian, but if you wanted to make them more severe, that decision really lies in Beijing. I'm not sure at this point that more could be accomplished by more sanctions. I think it's kind of a reflexive statement that policymakers make when put on the spot. The key here is to find a way to appropriately use the pressure of sanctions to produce a better outcome in diplomacy and to get on with what needs to be done on the Korean peninsula to end this ridiculous 65 years of hostility, long after a war between two systems that no longer even exist today, at one of their first showdowns after World War II.

ACT: The latest U.S. intelligence report foresees China doubling its nuclear stockpile over the next decade. Do you think that is accurate?

Biegun: I don't think we've spent sufficient time trying to understand what's happening in the strategic weapons program with China, and I think policymakers, arms control advocates, experts, scientists, and specialists need to devote substantially more time than we have. I think we've been neglectful in understanding this, and it is serious, and it is growing, and this is a substantial factor for U.S. national security. Quite honestly, it's a substantial factor for Russia's national security and for the world as well. China is the only country that's moving against the tide of the basic commitments made in the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) that nuclear-weapon states would be making efforts to reduce their nuclear weapons.

I expect that the purpose is the same as it's always been, to have a convincing deterrent in the case of conflict. But even if one accepts—and China is an accepted nuclear-weapon state—that they are going to have nuclear weapons, we need to devote a lot more effort to understanding their doctrine, to building new mechanisms for strategic stability between the United States and China. Basically, we have to kind of crack open some old playbooks and go back and think about how we can create a world that can remain free of the use of nuclear weapons at the same time that we're sustaining peace and security.

ACT: Even if the Chinese doubled their arsenal, they still wouldn't approach what the United States and Russia have. Yes, China is building up its stockpile but so are other countries, such as India and Pakistan. Don't we need to keep that in perspective?

Biegun: There are ample reasons to be worried about strategic stability, not only in the U.S.-Russian context, but the U.S.-Chinese context and in the context of other states. We've spent a long time talking about North Korea. Our commitment and China's commitment in the NPT is to commit to making efforts to reduce those nuclear weapons, not to increase them. It's not about what they owe us. It's about what their treaty commitments are internationally. This year, we have an NPT review conference where we hope China answers how its nuclear ambitions square with its commitments made in the NPT. From the U.S. and Russian points of view, I think certainly we should continue efforts to create a sound, stable, strategic formula that reduces nuclear weapons while maintaining the effectiveness of deterrents.

Ultimately, the ideal that so many advocate—the complete elimination of nuclear weapons—is well beyond our reach, but that doesn't mean we need more. I've personally never been an advocate of more. I've been an advocate for sound, treaty-based mechanisms that reduce weapons while sustaining stability. If we could do that with the Chinese, all the better, but I can tell you that there's nothing stabilizing for China or for the rest of the world that will come from a rapid expansion of their nuclear arsenal.