Is There a New Chance for Arms Control in the Middle East?

June 2021

By Marc Finaud, Tony Robinson, and Mona Saleh

Regional rivalries have long bedeviled the Middle East, and as a result, true arms control and security negotiations have never taken place. Several recent developments offer hope that the momentum for regional progress on nonproliferation and disarmament can be revived, provided some conditions are met.

The Abraham Accords formalized new relations between Israel and several Arab countries. Talks on restoring the Iran nuclear deal, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), are making headway while Iran and Saudi Arabia have resumed bilateral engagement thanks to mediation by Iraq. A return to full compliance with the JCPOA by the United States and Iran could be followed by broader discussions on regional security and missile programs.

The Abraham Accords formalized new relations between Israel and several Arab countries. Talks on restoring the Iran nuclear deal, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), are making headway while Iran and Saudi Arabia have resumed bilateral engagement thanks to mediation by Iraq. A return to full compliance with the JCPOA by the United States and Iran could be followed by broader discussions on regional security and missile programs.

In fact, a historic window of opportunity could be opening, all centered around the decades-old effort to establish a zone free of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) in the Middle East that was relaunched by a UN conference in 2019. Any optimism must be tempered by the latest surge in fighting between Israel and Hamas, but the diplomatic building blocks of future disarmament progress may be falling into place.

The Abraham Accords

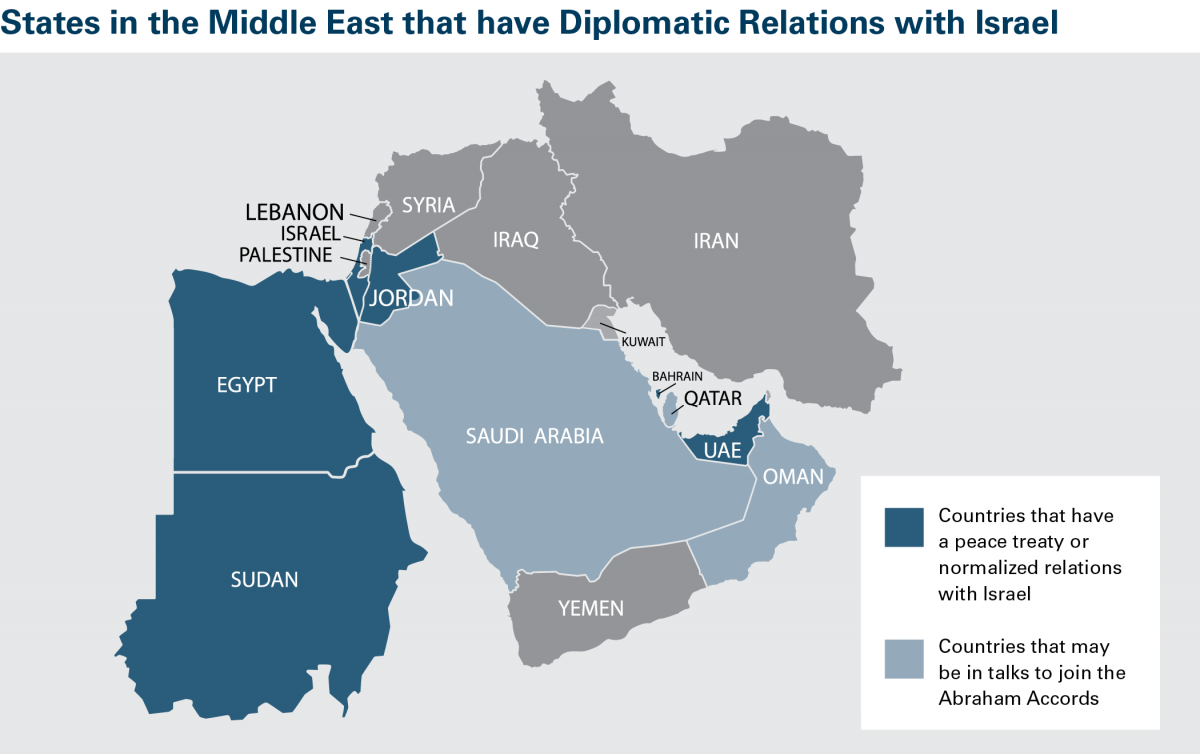

The Abraham Accords,1 concluded in August 2020 by Israel, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States and followed by the normalization agreements extended to Bahrain, Sudan, and Morocco with the door open for other Arab and Islamic states to join, are a potential game changer in the future of the region. Even if the main incentives for such agreements appear to be the prospect of major U.S. arms sales and an emerging coalition against Iran and despite their rejection by the Palestinians, the accords break the long-standing Arab taboo on normalizing relations with Israel.

Indeed, the accords dealt a heavy blow to the Arab consensus on the Saudi-led Arab Peace Initiative of 2002,2 which conditioned normalization with Israel on the establishment of a Palestinian state. They also upended the joint Arab position on the WMD-free zone, which required Israel to get rid of its nuclear weapons at an early stage in exchange for recognition and normalization under the “disarmament first” rubric. In that sense, the accords have divided Arab states due to their negative implications for the Palestinians and the two-state solution. The recent violence between Israel and the Palestinians put the Arab signatories of the accords in an embarrassing situation, underscoring the lack of support for normalization from the Arab “street” and the non-existent leverage of the Persian Gulf countries on Israel. In fact, the current situation demonstrates the centrality of the Palestinian issue that was recklessly ignored by the conclusion of the accords.

The accords are not as detailed as the peace treaties with Egypt from 1979 and Jordan from 1994 precisely because there is no history of direct armed conflict between the states-parties to the accords and Israel. Yet, they are a signal that the region is apparently moving beyond the old Arab-Israeli conflict and away from the refusal of most Arab states to recognize or engage openly in talks with Israel. Discreet trade relations between Israel and some Gulf countries had been laying the ground for normalization for years. The accords, particularly the agreement with the UAE3, list “spheres of mutual interests,” including investment, trade, science and technology, civil aviation, tourism, and energy, but their security dimension is the dominant one. They signal a willingness to enter into a new defense relationship and eventually possibly an alliance with Israel under U.S. auspices in order to counter “the Iranian threat.” This strategic ambition was reinforced when U.S. President Donald Trump shifted Israel out of the U.S. military’s European Command and to the U.S. Central Command, which includes other Middle Eastern countries.4

Rapprochement between Israelis and Arab countries, particularly the UAE, is in full swing on various levels from exchanging diplomatic missions to agreeing to visa-free travel and cooperating on maritime and civil aviation issues. The countries are collaborating on trade and banking matters and negotiating science and innovation deals. The UAE recently announced a $10 billion investment fund for strategic sectors in Israel.5 The accelerated collaborations, particularly in the maritime and aviation fronts, open the door to strengthening the security alliance between Israel and individual Gulf countries. The Israeli defense minister recently suggested that Israel intends to develop a “special security arrangement” with new Gulf allies who share common concerns about Iran.6

These developments are enhanced even more by the al-Ula Reconciliation Declaration of January 2021, in which all Gulf states agreed to solve the dispute between the “Quartet” (Bahrain, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE) and Qatar and to improve their “resistance” to Iran.7

Iran-Saudi Engagement

Recent reports about the first direct talks between Iran and Saudi Arabia since diplomatic ties were cut four years ago are extremely interesting and offer another glimpse of hope.8 They are a sign that an Iraqi mediation effort, initiated and brutally interrupted in January 2020 by the targeted killing by the United States of Major General Kassem Soleimani, the powerful Iranian commander, has regained momentum. After U.S. President Joe Biden announced the end of U.S. support for Saudi-led offensive operations in Yemen, Riyadh probably understood that, unlike during the Trump administration, it would not have everything its own way and might benefit from exploring a new political dynamic with Iran to stop a war it was not winning.

In the last months of Trump’s presidency, there was a clear impetus, led by Washington’s Gulf allies, to form an alliance in the region, including with new “friend” Israel, against Iran. It is likely that the Biden administration will not allow that to happen if it interferes with rescuing the faltering Iran nuclear deal, a key priority for Washington with widespread security implications for the region. Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif’s visit to Qatar, Oman, and Kuwait in April 2021 and his announced visit to the UAE reinforce the perception of warming ties in the Gulf and the prospects, at a minimum, of a positive impact on the conflict in Yemen where Iran is backing Houthis fighting Saudi-led forces with UAE assistance.

The Zone Itself

The question now is whether the Abraham Accords can have a direct impact on the ongoing efforts at negotiating a WMD-free zone in the Middle East. Despite a boycott by Israel and the United States, this process gained traction in 2019 at a UN General Assembly conference after the cancellation of the conference planned in 2012.9 When the conference, tentatively set for November 2021, reconvenes, one could logically expect a rift among states that have recently normalized relations with Israel, implicitly accepting Israel as a nuclear-armed state, and those still vocally against it. It is likely, however, that the unity of language on the zone will be preserved by the Arab League and that the accords will be largely ignored, in part because of the Arabs’ inevitable return to a more vocal pro-Palestinian stance.

It is clear that the Israeli nuclear weapons program, estimated to include 80 to 90 nuclear warheads, and its long-held policy of opacity were not on the table while the Abraham Accords were negotiated. Yet, they remain the elephant in the room. Indeed, the accords open the door for a de facto military alliance or “security arrangement,” for which the Israeli defense minister advocated, with the only nuclear-armed state in the region. Will this possible alliance be perceived by Iran, Saudi Arabia, or Turkey as a pretext to join the nuclear arms race? Could such a military alliance cause Israel to risk its military and technological edge? Will the lucrative arms exports to Gulf countries that Israel is contemplating contribute to making those countries faithful clients, willing to ignore Israel’s nuclear capability?10 There are no easy answers at this stage.

In the 47 years since the zone project has been under discussion, the Arabs have been calling for disarmament first. In contrast, Israel has consistently advocated peace first and avoided any talk of nuclear disarmament, arguing that the regional states need to travel down a “long corridor” of concrete actions for Israel to be reassured by mutual recognition, normalization, peace, and the establishment of a regional security architecture.11 Of course, Israel can claim that threats from Iran still justify maintaining nuclear deterrence. Yet, the reality of normalization with the Gulf states, a restored JCPOA followed by regional security talks, and the prospect of Israeli negotiations with the Palestinians, which could be encouraged by Biden given the surge of Israeli-Palestinian violence, may cause Israel to feel that the long corridor has shortened after all. Such improvement in the way Israel views its threat environment is hypothetical at this point and could be significantly affected by the military exchanges between Israeli and Hamas forces, the worst violence in seven years.

The Way Forward

The new Arab-Israeli and Gulf-Iranian rapprochements should be viewed as a fresh opportunity to engage regional parties to pursue serious arms control negotiations. The moment has come to call out the Abraham Accords for what they do not say and urge their signatories to make the links among peace, recognition, and normalization with Israel more explicit and for Israel to make a serious commitment toward negotiations on a region free of weapons of mass destruction.

Although the arms deals that come with the Abraham Accords may contribute to an aggravation of instability in an already overarmed region, they do have one silver lining: they test the validity and credibility of Israel’s commitment to the long corridor approach. The international community and civil society are now in a position to challenge Israel, as the accords show that the Arabs have taken several strides down the long corridor and it is Israel’s turn to take serious steps toward disarmament given that it has already accepted, since 1980, the long-term goal of a Middle Eastern WMD-free zone.

The wider regional security concerns, such as ballistic missiles and the involvement of some regional states in military conflicts beyond their borders, can be discussed within the framework of the zone negotiations given that Israel and its new Arab allies share the need to enhance their own security. Israel, despite its technological advantage, nuclear capability, and alliance with the United States, still feels threatened and in need of recognition by regional states. Some Arab states feel threatened by Iran and its nuclear and ballistic missile programs and need the United States as a security guarantor.

Any serious negotiations on wider regional security issues should not exclude or single out Iran. Tehran has hinted that such an inclusive framework would be acceptable once the nuclear deal is restored.12 The JCPOA is the best guarantee to restrain Iran’s nuclear ambitions. Given long-standing complaints by Israel and key Arab states that the deal does not address wider regional security issues, such as ballistic missiles or regional conflicts, they should be eager to use the UN General Assembly-mandated zone process to start multilateral negotiations on those contentious issues.

All stakeholders have decisive roles to play. The United States must ensure that recent Israel-Palestinian violence is stopped and that the JCPOA is restored; more actively support engagement and reconciliation between parties still in conflict, such as Iran and the Arab countries, Israel and the Palestinians, and eventually Iran and Israel, in order to reduce external intervention in regional disputes; and provide security guarantees to the countries that seek them. Iran can only benefit from reintegration into a regional security framework if it does its part to restore the JCPOA. The other parties to the JCPOA—China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the European Union—should not only facilitate full compliance with the Iran nuclear deal but also actively support regional security talks. Israel should seize this opportunity to invest in and advance the regional security architecture it says it wants. That should at some point include peace negotiations with the Palestinians. The Arab states should seek security assurances from the United States and Israel that could avoid a nuclear arms race in the region. Finally, civil society should take advantage of this fragile rapprochement to convince their governments that the region needs less armaments and more human security.

Endnotes

1. See Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs, U.S. Department of State, “The Abraham Accords,” n.d., https://www.state.gov/the-abraham-accords/ (accessed May 19, 2021).

2. “Arab Peace Initiative: Full Text,” March 28, 2002, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2002/mar/28/israel7.

3. U.S. Department of State, “Abraham Accords Peace Agreement: Treaty of Peace, Diplomatic Relations and Full Normalization between the United Arab Emirates and the State of Israel,” https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/UAE_Israel-treaty-signed-FINAL-15-Sept-2020-508.pdf.

4. Brian W. Everstine, “Pentagon Shifts Israel to CENTCOM Responsibility,” Air Force Magazine, January 15, 2021.

5. “UAE Announces $10 Billion Fund for Israel Investments,” The Arab Weekly, March 12, 2021.

6. Dan Williams, “Israeli Defense Chief Sees ‘Special Security Arrangement’ With Gulf States,” Reuters, March 2, 2021.

7. Tuqa Khalid, “Full Transcript of the AlUla GCC Summit Declaration: Bolstering Gulf Unity,” Al Arabiya English, January 6, 2021.

8. “Saudi and Iran Held Talks Aimed at Easing Tensions, Say Sources,” Reuters, April 18, 2021.

9. Conference on the Establishment of a Middle East Zone Free of Nuclear Weapons and Other Weapons of Mass Destruction, Report of the first session, A/CONF.236/6, November 22, 2019]

10. Arie Egozi, “Israeli Defense Minister Goes Slow on Arab Weapon Sales,” Breaking Defense, April 2, 2021.

11. Eitan Barak, “The Beginning of the End of the Nuclear Age,” Haaretz, January 26, 2021.

12. Negar Mortazavi, “What It Will Take to Break the U.S.-Iran Impasse: A Q&A With Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif,” Politico, March 17, 2021.

Marc Finaud is head of arms proliferation at the Geneva Centre for Security Policy. Tony Robinson is director of the Middle East Treaty Organization. Mona Saleh is a doctoral research fellow at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies.