Volume 9, Issue 5, July 17, 2017

The future of U.S. nuclear weapons and missile defense policy is at a crossroads. The Trump administration is conducting comprehensive reviews—scheduled to be completed by the end of the year—that could result in significant changes to U.S. policy to reducing nuclear weapons risks.

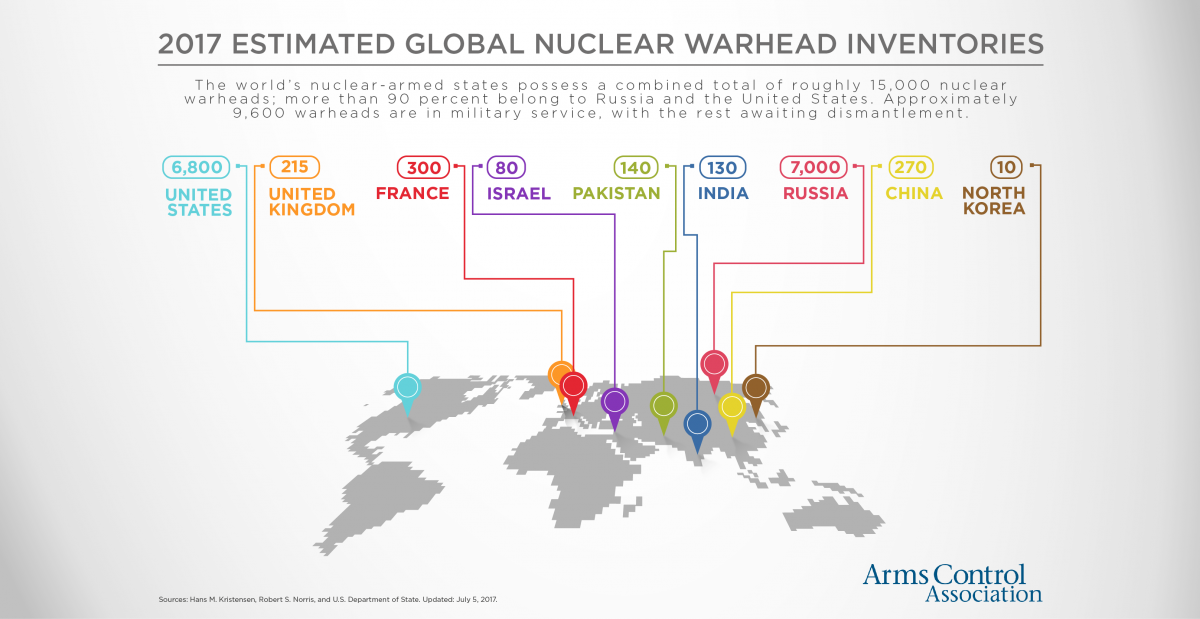

As the possessors of over 90 percent of the world's roughly 15,000 nuclear weapons, the United States and Russia have a special responsibility to avoid direct conflict and reduce nuclear risks. Yet, the U.S.-Russia relationship is under significant strain, due to to Moscow’s election interference, annexation of Crimea, continued destabilization of Ukraine, and support for the brutal Assad regime in Syria. These tensions have also put put immense pressure on the arms control relationship.

It is against this backdrop that the House and Senate Armed Services Committee versions of the Fiscal Year (FY) 2018 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) include provisions that if passed into law would deal a major, if not mortal, blow to longstanding, bipartisan arms control efforts.

The House approved its version of the NDAA July 14 by a vote of 344-81 and the Senate could take up its bill later this month.

The problematic arms control provisions in the bills would undermine U.S. security by eroding stability between the world's two largest nuclear powers, increasing the risks of nuclear competition, and further alienating allies already unsettled by President Donald Trump’s commitment to their security. In fact, some are so radical that they have even drawn opposition from the White House and Defense Department.

The bills also fail to provide effective oversight of the rising costs of the government’s more than $1 trillion-plan to sustain and upgrade U.S. nuclear forces and propose investments in expanding U.S. missile defenses that make neither strategic, technical, or fiscal sense.

Sowing the Seeds of the INF Treaty’s Destruction

The United States has accused Russia of testing and deploying ground-launched cruise missiles (GLCMs) in violation of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty. The treaty, which remains in force, required the United States and the then-Soviet Union to eliminate and permanently forswear all their nuclear and conventional ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges of 500 to 5,500 kilometers.

Both the House and Senate versions of the NDAA authorize programs of record and provide funding for research and development on a new U.S. road-mobile GLCM with a range of between 500 and 5,500 kilometers. The House bill requires development of a conventional missile whereas the Senate bill would authorize a dual-capable (i.e., nuclear) missile.

The House bill also includes a provision stating that if the president determines that Russia remains in violation of the treaty 15 months after enactment of the legislation, the prohibitions set forth in the treaty will no longer be binding on the United States. A similar provision could be offered as an amendment to the Senate bill.

These provisions are drawn from legislation introduced in February by Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) in the Senate and Rep. Mike Rogers (R-Ala.) in the House to “provide for compliance enforcement regarding Russian violations” of the INF Treaty.

Development of a new treaty-prohibited GLCM is militarily unnecessary, would suck funding from other military programs for which there are already requirements, divide NATO, and give Russia an easy excuse to publicly repudiate the treaty and deploy large numbers of noncompliant missiles without any constraints.

The report accompanying the Senate bill notes that the Senate “does not intend for the United States to enter into violation of the INF Treaty.” (The treaty does not ban research and development of treaty-prohibited capabilities.) But this claim is belied by the report’s statement that development of a GLCM is needed to “close the capability gap opened” by Russia. Moreover, supporters of a new GLCM also argue it is needed to counter China, which is not a party to the treaty.

Before rushing to develop a new weapon that the Pentagon has yet to ask for and NATO is unlikely to support, the administration and Congress must at the very least address concerns about the suitability and cost-effectiveness of a new GLCM. Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.) offered an amendment to the bill on the House floor that would have done just that, but it was defeated by a vote of 173-249.

Meanwhile, mandating that the United States in effect withdraw from the treaty if Russia does not return to compliance by the end of next year raises constitutional concerns. If Congress can say the United States is not bound by its obligations under the INF Treaty, what is to stop it from doing the same regarding other treaties?

The administration's statement of policy on the House NDAA objected to the House INF provision on requiring a new GLCM, stating "[t]his provision unhelpfully ties the Administration to a specific missile system, which would limit potential military response options.” The statement also noted that bill would “raise concerns among NATO allies and could deprive the Administration of the flexibility to make judgments about the timing and nature of invoking our legal remedies under the treaty.”

Instead of responding to Russia’s violation by taking steps that could leave the United States holding the bag for the INF treaty’s demise, Congress should emphasize the importance of preserving the treaty and encourage both sides to more energetically pursue a diplomatic resolution to the compliance controversy. Lawmakers should also encourage the Trump administration to pursue firm but measured steps to ensure Russia does not gain a military advantage by violating the treaty and reaffirm its commitment to the defense of those allies that would be the potential targets of Russia’s noncompliant missile.

Cutting Off Our Nose to Spite Our Face on New START

One of the few remaining bright spots in the U.S.-Russia relationship is 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START). Signed in 2010, the treaty requires each side to reduce its deployed strategic nuclear forces to no more than 1,550 warheads and 700 delivery systems by 2018. It also includes a comprehensive suite of monitoring and verification provisions that help ensure compliance with these limits.

The agreement, which is slated to expire Feb. 5, 2021, can be extended by up to five years if both Moscow and Washington agree. The House bill includes a provision that would prohibit the use of funds to extend New START until Russia returns to compliance with the INF treaty. This is senseless and counterproductive. By “punishing” Russia’s INF violation in this way, the United States would simply free Russia to expand the number of strategic nuclear weapons pointed at the United States after New START expires in 2021.

If the treaty is allowed to lapse, there will be no limits on Russia’s strategic nuclear forces for the first time since the early-1970s. Moreover, the United States would have fewer tools with which to verify the size and composition of the Russian nuclear stockpile.

For these reasons and more, the U.S. military and U.S. allies continue to strongly support New START.

Undermining the Norm Against Nuclear Testing

A small but influential group of Republican lawmakers are seeking to cut U.S. funding for the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO) and undermine international support for the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) and the global nuclear test moratorium.

Sen. Cotton and Rep. Joe Wilson (R-S.C.) introduced legislation on Feb.7 to “restrict” funding for the CTBTO and undermine the U.S. obligation – as a signatory to the 1996 Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty – not to conduct nuclear test explosions.

Rep. Wilson successfully offered the bill as an amendment to the House NDAA and Sen. Cotton could seek to do the same on the Senate bill.

With North Korea threatening to conduct a sixth nuclear test explosion, it is essential that the United States reinforce, not weaken, the global nuclear testing taboo.

More information on the problematic provision in the House bill is detailed in a recent issue brief on CTBTO funding.

Nuclear Weapons Spending Run Amok

The Trump administration’s first Congressional budget request pushes full steam ahead with the Obama administration’s excessive, all-of-the-above approach to upgrading the U.S. nuclear arsenal. Both the House and Senate bills authorize the requested level of funding for these programs, and even increase funding for some programs beyond what the Trump administration requested.

As the projected costs for programs designed to replace and upgrade the nuclear arsenal continue to rise, Congress must demand greater transparency about long-term costs, strengthen oversight over high-risk programs, and consider options to delay, curtail, or cancel programs to save taxpayer dollars while meeting deterrence requirements.

A February 2017 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report estimates that the United States will spend $400 billion (in then-year dollars) on nuclear weapons between fiscal years 2017 and 2026. The new projection is an increase of $52 billion, or 15 percent, over the CBO’s most recent previous estimate of the 10-year cost of nuclear forces, which was published in January 2015 and put the total cost at $348 billion.

In fact, the CBO’s latest projection suggest that the cost of nuclear forces could greatly exceed $1 trillion over the next 30 years.

What makes the growing cost to sustain the nuclear mission so worrisome for military planners is that costs are scheduled to peak during the mid-2020s and overlap with large increases in projected spending on conventional weapon system modernization programs. Numerous Pentagon officials and outside experts have warned about the affordability problem posed by the current approach and that it cannot be sustained without significant and sustained increases to defense spending or cuts to other military priorities.

Unfortunately, the House rejected two Democratic floor amendments that would have shed greater light on the multidecade costs of U.S. nuclear forces. One amendment would have required CBO to extend the timeframe of its biennial report on the cost of nuclear weapons from 10 years to 30 years. Another would have required extending the timeframe of a Congressionally mandated report submitted annually by Defense Department and National Nuclear Security Administration from 10 years to 25 years.

In addition, the House defeated by a vote of 169-254 an amendment offered by Rep. Blumenauer that would have restricted funding for the program to develop a new fleet of nuclear air-launched cruise missiles at the FY 2017 enacted level until the administration completes its Nuclear Posture Review and a detailed assessment of the need for the program.

Though the administration requested a major increase for the new missile and associated warhead refurbishment program in FY 2018, Defense Secretary James Mattis has repeatedly stated that he is still evaluating the need for the weapon.

The House Rules Committee also prevented debate on a floor amendment that would have required the Pentagon to release the value of the contract awarded to Northrop Grumman Corp. in October 2015. The department has refused to release the contract value citing classification concerns.

Tripling-Down on Missile Defense Despite Technical Flaws

Both the House and Senate bills authorize significant increases in funding for U.S. ballistic missile defense programs. The House bill authorizes an increase of $2.5 billion above the administration’s FY 2018 budget request of $7.9 billion for the Missile Defense Agency. The Senate bill authorizes a $630 million increase.

The bills also include provisions that would authorize a significant expansion of the ground-based midcourse (GMD) defense system in Alaska and California, which is designed to protect against limited long-range ballistic missile attacks from North Korea or Iran, and accelerate advanced technology programs to increase the capability of U.S. missile defenses. The GMD system has suffered from numerous reliability problems and has a success rate of just over 50 percent in controlled and scripted flight intercept tests.

In addition, the House bill includes a provision that would require the Pentagon to submit a plan for the development of a space-based missile defense interceptors and authorize $30 million for a space test bed to conduct research and development on such interceptors. The House bill would also require the Pentagon, pursuant to improving the defense of Hawaii, to conduct an intercept test of the Standard Missile-3 (SM-3) Block IIA missile against an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) target. The interceptor, which is still under development, is designed to defend against medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missiles and the department has no public plans to test it versus an ICBM.

Rushing to deploy more unreliable GMD interceptors or building additional long-range interceptor sites is not a winning strategy to stay ahead of the North Korean ICBM threat. Quantity is not a substitute for quality.

Any consideration of building and deploying additional homeland interceptors or interceptor sites should wait until a new ground-based midcourse defense kill vehicle under development is successfully tested under operationally realistic conditions (including against ICBM targets and realistic countermeasures). The first test of the new kill vehicle under these conditions is not scheduled until 2020 and deployment is not scheduled until 2022.

In addition, future testing and deployment of new capabilities should not be schedule-driven, but based on the maturity of the technology and successful testing under operationally realistic conditions. Accelerating development programs risks saddling them with cost overruns, schedule delays, and test failures, as has been the case with previous missile-defense programs.

Despite numerous nonpartisan studies that have been conducted during both Republican and Democratic administrations which concluded that a spaced-based missile defense is unfeasible and unaffordable, a small faction of missile defense supporters continues to push the idea. Most recently, a 2012 report from the National Academy of Sciences declared that even a limited space system geared to longer-burning liquid fueled threats would cost about $200 billion to acquire and have a $300 billion 20-year life cycle cost (in FY 2010 dollars), which would be at least 10 times any other defense approach.

While missile defense has a role to play as part of a comprehensive strategy to combat the North Korean missile threat, it’s neither as capable nor as significant as many seem to hope. More realism is needed about the limitations of defenses and the longstanding obstacles that have prevented them from working as intended.

The potential blowback of an expansion of U.S. missile defense capabilities from Russia and China must also be considered. Missile defense does not provide an escape route from the vulnerability of our allies, deployed forces, and citizens in the region to North Korea’s nuclear and conventional missiles.—KINGSTON REIF, director for disarmament policy