The Unknowns About China’s Nuclear Modernization Program

June 2023

By Fiona S. Cunningham

Policymakers and scholars outside of China do not know why Beijing is rapidly modernizing its nuclear arsenal.

This uncertainty makes it more difficult for the United States and allied governments in the Indo-Pacific region and Europe to make informed choices about deterring China from the use of conventional or nuclear force and avoiding policies that exacerbate nuclear dangers. Although some changes to China’s nuclear capabilities and nuclear operations are observable, they do not provide clear evidence about what kind of nuclear arsenal China ultimately seeks and for what purpose. There is a broad range of goals that China might pursue. Regardless of its ambitions, it will take time for China to achieve these goals because of the modest arsenal that was the starting point for the current modernization effort.

This uncertainty makes it more difficult for the United States and allied governments in the Indo-Pacific region and Europe to make informed choices about deterring China from the use of conventional or nuclear force and avoiding policies that exacerbate nuclear dangers. Although some changes to China’s nuclear capabilities and nuclear operations are observable, they do not provide clear evidence about what kind of nuclear arsenal China ultimately seeks and for what purpose. There is a broad range of goals that China might pursue. Regardless of its ambitions, it will take time for China to achieve these goals because of the modest arsenal that was the starting point for the current modernization effort.

Open-source analysis offers some clues about the drivers of China’s actions, but more research is needed to discover whether there is a coherent motivation underlying its nuclear modernization and, if so, what it is.

Analyzing just the capabilities that China is developing raises as many questions as it answers, for example. China is building capabilities that improve its ability to retaliate following a nuclear attack and its ability to threaten nuclear first use for coercive leverage in a conventional conflict. It can now do things with nuclear forces that it could not do in the past.

This change undermines the previous confidence of policymakers and analysts outside of China that Chinese leaders likely would use nuclear weapons only in desperation. It also raises other questions. Why did China wait until now to build a much more robust retaliatory capability? Why is it investing in silo basing after two decades of seeking a more mobile nuclear force to increase the survivability of its arsenal? Is it developing capabilities that could enable a quicker shift to a first-use posture in the future as a hedge or for other reasons?

There are a number of possible factors driving China’s nuclear modernization. New research indicates that developments in U.S. capabilities are responsible at least partly for the changes, but China’s reaction to such developments is more dramatic than in the past, which suggests that other factors likely are at play. China’s pursuit of a stronger nuclear shield, whether to enable conventional military operations or the non-nuclear escalation of a conflict, is one possibility. Another possibility is a change in China’s nuclear posture to embrace the first use of nuclear weapons, although so far there is not much evidence of this. A final possibility, for which there is limited evidence, is that changes in thinking among Chinese leaders and among bureaucratic actors who influence China’s nuclear policymaking are shaping modernization decisions.

A Thin Margin for Error

Until approximately 2019, three key characteristics defined China’s post-Cold War nuclear posture: a retaliatory doctrine, a small arsenal, and strict civilian control of nuclear weapons use. Although China’s no-first-use policy for its nuclear weapons generated a healthy degree of skepticism, it informed the goals that China’s nuclear forces were intended to achieve: countering an adversary’s efforts to compel or “blackmail” China with nuclear weapons in a conventional conflict and assuring retaliation if China suffers a nuclear attack.1 Chinese officials continue to reaffirm this no-first-use policy today.

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) always could have improvised a nuclear first-strike campaign if called on by political leaders to do so. Some Chinese experts wrote about ambiguities in China’s no-first-use policy and proposed exceptions to it, especially in the early 2000s.2 Yet, there is no evidence that Chinese leaders ever officially accepted these proposals or adopted a first-use policy to gain a coercive or military advantage as a goal for its nuclear forces. Instead, they relied on threats to escalate a conflict using information-age weapons with strategic effects—precision conventional missiles, counterspace weapons, and cyberattacks—to gain coercive leverage as substitutes for threatening nuclear first use.3

China has maintained an arsenal of roughly 200 to 300 nuclear warheads and delivery systems throughout most of the last three decades. The rapid growth of its conventional missile force since the late 1990s suggests that China could have built a much larger nuclear force if it had wanted. Even in 2020, as the U.S. government began to project rapid growth in China’s nuclear arsenal, The Science of Military Strategy, published by the PLA National Defense University in 2020, reaffirmed the PLA’s force-building principle of a “lean and effective” arsenal.4 The meaning of “lean and effective,” however, was never meant to be a fixed number, but rather one that would ensure China’s retaliatory capability despite the improving counterforce capabilities fielded by China’s nuclear adversaries.

China always has concentrated control over nuclear operations in the hands of top civilian leaders to avoid the accidental or unauthorized use of nuclear weapons, even at the expense of the survivability of its arsenal.5 The Politburo Standing Committee and the Central Military Commission must both agree to put nuclear weapons on alert or launch them. China’s land-based nuclear forces were kept at a low level of peacetime readiness. Warheads were stored at a central depot while missiles remained in garrisons dispersed throughout the country’s vast territory, unless its leaders issued an order for warheads to be dispatched from the central warhead depot to missile units.6

A Changing Nuclear Force

Since around 2019, China has increased the size, accuracy, readiness, and diversity of its nuclear arsenal. The number of Chinese nuclear warheads and delivery systems is increasing. In 2022, the Pentagon report on Chinese military power estimated that its number of nuclear warheads exceeded 400,7 while an unofficial estimate put the current Chinese stockpile at 410.8 The Pentagon forecasts that China’s operational warhead stockpile will grow to 1,000 by 2030 and to 1,500 by 2035 “if China continues the pace of its nuclear modernization,” although it is far from certain that the future pace of China’s arsenal growth will be constant.

China also has improved the accuracy of its land-based nuclear delivery systems. Media reports indicate that China’s newest intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), the solid-fueled Dongfeng (DF)-41, has a circular error probability of 100 meters.9 Its most advanced theater-range delivery system, the DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile, is more accurate than the older DF-21 missile.10 No information is publicly available about the accuracy of air- or submarine-launched nuclear delivery systems or accuracy improvements to older land-based missiles.

China has increased the readiness of its land-based missile force and amended its long-standing practice of separating warheads and delivery systems in peacetime. In 2021, the Pentagon report on Chinese military power stated that although China “almost certainly keeps the majority of its nuclear force on a peacetime status—with separated launchers, missiles, and warheads—nuclear and conventional…PLARF [People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force] brigades conduct ‘combat readiness duty’ and ‘high alert duty,’ which apparently include assigning a missile battalion to be ready to launch, and rotating to standby positions as much as a monthly basis for unspecified periods of time.”11 In new analysis, David Logan and Phillip Saunders found some evidence that the PLARF’s nuclear-warhead handling regiments, which used to be subordinated to missile bases, are now under the authority of the central warhead depot. They suggest that this change might reflect an intent to shore up centralized control arrangements while adopting more distributed warhead handling practices.12

The higher readiness level could enable a future shift to a launch-on-warning alert status for some or all of China’s nuclear forces. The 2022 Pentagon report indicated that China is implementing such a change, citing rapid improvements in its early-warning system and PLA writings and Rocket Force exercises.13 Because constructing an early-warning system has a long lead time, however, the available evidence is also consistent with China putting in place the pieces to enable a shift to a launch-on-warning alert status in the future.

Indeed, China’s current early-warning system still has important weaknesses that likely would result in relatively short warning times of a U.S. missile launch by the time China has confirmed that it was the target of the strike.14 Although various editions of The Science of Military Strategy included language suggesting China’s land-based missile force would move to a launch-on-warning posture,15 Chinese experts have been debating the costs and benefits of moving to a launch-on-warning alert status for almost a decade. One recent study by Henrik Hiim, Taylor Fravel, and Magnus Langset Trøan analyzing Chinese sources found evidence of discussion but no clear decision to adopt a launch-on-warning alert status.16 If leaders in Beijing have already decided to adopt this change, available evidence does not clarify how they are amending nuclear launch procedures and authorities to take account of the shortened decision time required for timely launch.

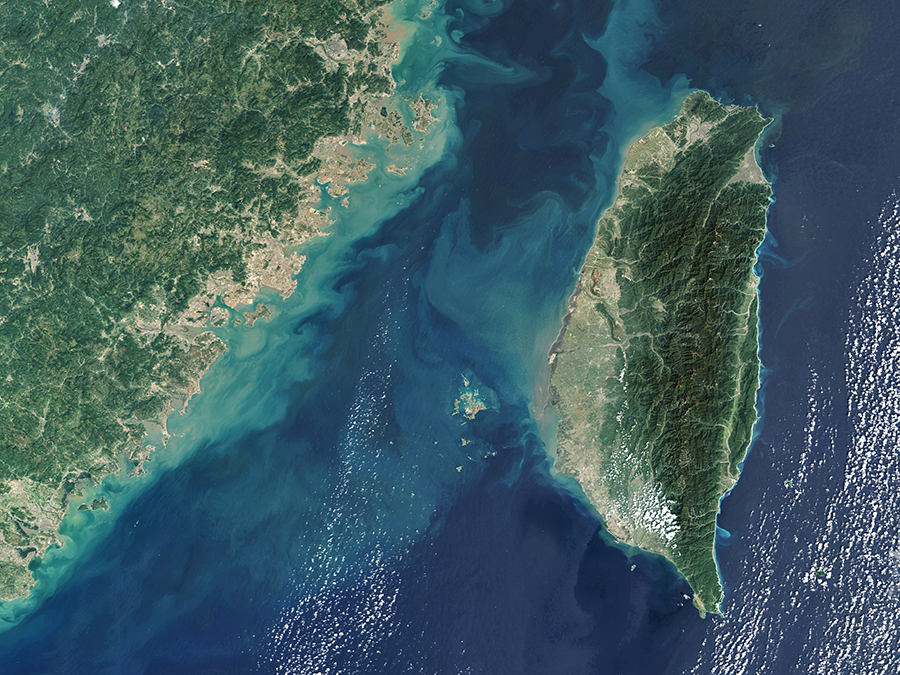

China’s nuclear modernization has added to the diversity of its nuclear systems, which gives its leaders better options for theater nuclear strikes, redundancy in delivery systems, and some experimental systems whose applications remain unclear. China’s nascent nuclear triad has increased its options for nuclear strikes in the East Asian theater. The air leg currently depends on the H-6N bomber, which has a range of approximately 3,500 kilometers and can be refueled. It lacks stealth capabilities to overcome sophisticated air defenses, but is expected to be equipped with a medium-range air-launched ballistic missile. Similarly, the Type-094 submarine would be vulnerable to U.S. anti-submarine warfare forces if it transited through the first island chain to bring the continental United States into range of its JL-2 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). At least some of those submarines now carry the longer-range JL-3 SLBM, but they would still have to exit the first island chain to bring the eastern coast of the United States into range.17

The air and sea legs of China’s nuclear forces likely will become more significant for intercontinental-range nuclear operations when next-generation platforms that have greater range and stealth capabilities come online. China also has improved the land-based leg of its theater-range nuclear delivery systems. Its newer, dual-use DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile can deliver anti-ship, conventional and nuclear warheadsand reportedly is more mobile and survivable than the older DF-21A medium-range ballistic missile.18 In a departure from operational practices for the DF-21, which had different brigades operating conventional, conventional anti-ship, and nuclear variants of the missile, the same DF-26 brigades appear to train for conventional and nuclear missions.19

China’s new missile silos increase the diversity of its land-based intercontinental-range nuclear delivery systems. After the PLARF spent nearly three decades moving away from silo-based nuclear forces, it began constructing three large silo fields in 2020 and 2021 consisting of roughly 100 silos each. Those silos could be filled with China’s most advanced ICBM, the DF-41, which is solid fueled and can carry multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles, or the older DF-31 series ICBM, which is also solid fueled but delivers a single warhead.

China’s new missile silos increase the diversity of its land-based intercontinental-range nuclear delivery systems. After the PLARF spent nearly three decades moving away from silo-based nuclear forces, it began constructing three large silo fields in 2020 and 2021 consisting of roughly 100 silos each. Those silos could be filled with China’s most advanced ICBM, the DF-41, which is solid fueled and can carry multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles, or the older DF-31 series ICBM, which is also solid fueled but delivers a single warhead.

China also has been constructing silos near existing brigades that operate its oldest ICBM, the silo-based, liquid-fueled DF-5. Various editions of The Science of Military Strategy have indicated that fixed and mobile missile units each have their advantages and disadvantages. Silos are able to keep their status secret and conceal pre-launch preparations, but are vulnerable once discovered by an adversary.20 The rapid expansion of a silo-based ICBM force could reflect an intent to adopt a launch-on-warning alert status, as the Pentagon report speculated. It also could reflect Chinese concerns about the disadvantages of land-based mobile nuclear forces, whether their survivability, mobility, communications, or cost.

China is experimenting with capabilities that could further increase the future diversity of its nuclear forces. It has tested experimental delivery systems, such as an orbital bombardment system paired with a hypersonic glide vehicle. U.S. officials have hinted that China is developing “novel nuclear-powered capabilities.”21 The Pentagon also reported that China might be developing low-yield nuclear warheads for its nuclear delivery systems, citing Chinese defense industry publications expressing an interest in low-yield options and activity at China’s nuclear laboratories and testing sites.22 Whether and how China might deploy these systems remain unclear.

Inferring Motivations From Capabilities

The increasing size, accuracy, readiness, and diversity of China’s arsenal bolsters the credibility of the country’s ability to threaten retaliation for a nuclear strike and enables China to make more credible threats to use nuclear weapons first. As such, there are clear limits to inferring China’s nuclear goals and motivations from its capabilities.

Less than a decade ago, China had a thin margin for error in ensuring the survivability of its retaliatory force, which depended heavily on the alert status of its small number of mobile ICBMs. One study concluded that, in 2017, 10 to 27 Chinese warheads would survive a U.S. disarming strike, assuming a low alert status.23 Another study by two U.S. scholars found that China could likely deliver 10 to 20 warheads to the continental United States, assuming China alerted its mobile land-based ICBMs early in a crisis.24 A Chinese scholar determined that, in 2010, “the probability of successful Chinese nuclear retaliation against the continental United States was 38 percent for day-to-day alert status, and 90 percent for full alert status.”25

Today, China’s nuclear retaliatory capability is more robust. A larger arsenal is better able to absorb a disarming strike and penetrate U.S. missile defenses. The fastest growth in China’s arsenal between 2015 and 2020 occurred in its dual-use DF-26 force, when 160 to 250 launchers were added.26 The country’s ICBM force also has grown substantially from approximately 60 missiles in 2015 to 140 missiles by unofficial estimates and 300 according to the Pentagon in late 2022.27

China’s new silo fields suggest that the majority of future growth will be in its ICBM force. The higher readiness of some Chinese units in peacetime deprives the United States of the opportunity to neutralize China’s retaliatory capability by disrupting the process of mating warheads and delivery systems in a crisis or conflict. The greater diversity of China’s nuclear force adds further redundancy that hedges against the increased vulnerability of its land-based missile forces to U.S. counterforce capabilities in the future. The DF-26 missile also equips China with a larger number of more accurate and survivable options for limited retaliation.

In 2015, China could have threatened the first use of nuclear weapons, but it lacked a sufficient number of accurate capabilities for limited strikes to make those threats credible. A limited Chinese first strike to gain coercive leverage in a conventional conflict would have been suicidal unless Chinese leaders were very confident the United States would back down rather than retaliate. China’s nuclear modernization enables its leaders to make more credible threats of nuclear first use, but still it is not optimized for coercion in conventional conflicts. One key missing capability is a large or diverse set of theater or tactical nuclear capabilities for limited nuclear strikes. Nevertheless, as China’s nuclear arsenal continues to grow, the acute trade-off it previously faced between engaging in a limited nuclear exchange and deterring a disarming U.S. strike will ease. The higher peacetime readiness of some Chinese land-based nuclear missile units would give the United States less warning of a Chinese first strike and fewer opportunities to preempt it. The accuracy of the DF-26 missile creates new possibilities for China to carry out limited nuclear strikes by reducing the likelihood that these limited, theater-range nuclear strikes would cause collateral damage that risks provoking more devastating retaliation than intended.

Because China’s capabilities provide only limited insights into Chinese motivations for building up its nuclear forces, any search for additional insights should consider the drivers of China’s nuclear posture in the past and the drivers of other countries’ nuclear force developments. There are a number of possible motivations for China’s nuclear modernization, some suggesting continuity in the country’s nuclear strategy goals and others suggesting change in those goals or in the nuclear posture decision-making processes in China.

Assuring Robust Retaliation

To ensure that China could retaliate for nuclear attacks and deter nuclear coercion in a crisis or conventional war, Chinese nuclear strategists have long recognized that its arsenal needs to evolve in tandem with the first-strike threat that it faces. Since 2015, improvements in U.S. counterforce capabilities, such as missile defenses, sensing capabilities, and conventional precision strikes, have prompted changes in the implementation of China’s nuclear strategy to shore up its retaliatory capability.28 Chinese experts have continued to follow U.S. missile defense developments carefully, including expansion of interceptor numbers and interest in space-based defenses discussed by the Pentagon’s 2019 Missile Defense Review,29 and a Standard Missile-3 missile interceptor test on an ICBM in late 2020.

Chinese strategists also are concerned by perceived U.S. moves to “lower the nuclear threshold” by threatening to retaliate for counterspace and cyberattacks, as implied in the report of the 2018 U.S. Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), and the low-yield supplemental capabilities that the Biden administration retained in the NPR report released last year.30 These concerns likely are driven by questions about how China might deter or respond to U.S. limited strikes. One recent study indicates that Chinese experts also are more concerned than previously about U.S. conventional strike capabilities and stronger U.S. incentives to use nuclear weapons first in a conflict with China.31

Chinese strategists also are concerned by perceived U.S. moves to “lower the nuclear threshold” by threatening to retaliate for counterspace and cyberattacks, as implied in the report of the 2018 U.S. Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), and the low-yield supplemental capabilities that the Biden administration retained in the NPR report released last year.30 These concerns likely are driven by questions about how China might deter or respond to U.S. limited strikes. One recent study indicates that Chinese experts also are more concerned than previously about U.S. conventional strike capabilities and stronger U.S. incentives to use nuclear weapons first in a conflict with China.31

Although the concerns of Chinese experts about the adequacy of China’s retaliatory capability have been steadily increasing, they have not increased so dramatically as to offer a fully satisfying explanation for the unprecedented nuclear modernization effort. Specifically, expert views cannot account for two important adjustments in China’s response to U.S. counterforce capabilities. First, China now appears determined to develop a much more robust retaliatory capability that sets a higher threshold for unacceptable damage to deter the United States. China most likely wants to eliminate the U.S. capability to limit damage from a Chinese retaliatory nuclear strike. Although the U.S. damage limitation capability was already thin and diminishing in 2016,32 Chinese experts at that time did not believe that capability gave Washington much coercive leverage. They were confident that the United States would view the level of damage that China could inflict in a nuclear retaliatory strike as sufficient for deterrence even if that level of damage fell well short of the Cold War standard of assured destruction.

Second, China is acquiring a more sophisticated capability for limited nuclear retaliation, relying mainly on its accurate DF-26 missile. Before 2019, Chinese experts indicated that the country’s modest arsenal, which included a small number of inaccurate theater-range nuclear weapons and strategic nuclear forces, were sufficient to deter limited attacks.33 China could still develop a much more formidable theater nuclear force than it is currently fielding. There is little evidence linking the DF-26 missile capability to operations for limited retaliation.34 These two adjustments in China’s response to U.S. counterforce capabilities signal a departure from the more relaxed view of how much is enough to deter an adversary that, until recently, characterized China’s nuclear posture. Many nuclear strategists would consider these changes to be reasonable, stabilizing, and overdue measures to entrench a nuclear stalemate between the United States and China. The question remains why they are finally occurring now.

Second, China is acquiring a more sophisticated capability for limited nuclear retaliation, relying mainly on its accurate DF-26 missile. Before 2019, Chinese experts indicated that the country’s modest arsenal, which included a small number of inaccurate theater-range nuclear weapons and strategic nuclear forces, were sufficient to deter limited attacks.33 China could still develop a much more formidable theater nuclear force than it is currently fielding. There is little evidence linking the DF-26 missile capability to operations for limited retaliation.34 These two adjustments in China’s response to U.S. counterforce capabilities signal a departure from the more relaxed view of how much is enough to deter an adversary that, until recently, characterized China’s nuclear posture. Many nuclear strategists would consider these changes to be reasonable, stabilizing, and overdue measures to entrench a nuclear stalemate between the United States and China. The question remains why they are finally occurring now.

New Ambitions?

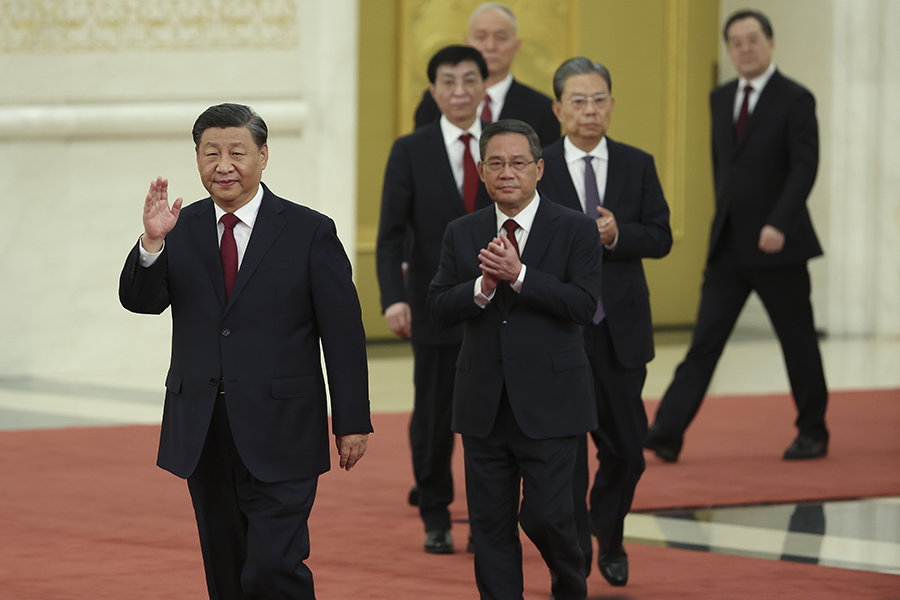

One possibility is that a conventional conflict between the United States and China appears more likely today than five or 10 years ago. According to U.S. civilian officials and military leaders, Chinese President Xi Jinping, who commands the PLA as chairman of the Central Military Commission, has instructed the PLA to attain the capability to achieve reunification with Taiwan by force by 2027. Preparing for this conventional contingency might have led China’s leaders to reexamine the adequacy of its nuclear force structure. Some U.S. experts have argued that China likely is seeking a stronger retaliatory capability as a nuclear shield to ensure that it could conduct conventional operations without worrying about U.S. nuclear coercion.35 Beijing might seek that shield against U.S. threats either to use nuclear weapons first for coercive leverage or to attack China’s nuclear arsenal using its counterforce capabilities. Concerns that China might rely on a nuclear shield to enable conventional operations across the Taiwan Strait have only deepened since Russia began to issue nuclear threats during its war in Ukraine to deter NATO’s direct military involvement.

A key assumption underlying this nuclear shield argument is that PLA conventional military operational planning influences China’s nuclear planning. Yet, until at least 2019, China’s decisions to continue its nuclear strategy had been decoupled from its decisions to change its conventional military strategy.36 PLA leaders promulgated a new generation of operational regulations in November 2020, which might have created an opportunity to address this decoupling. Yet, there is little evidence to support the possibility of tighter integration of China’s nuclear and conventional strategy, planning, or force building.

A key assumption underlying this nuclear shield argument is that PLA conventional military operational planning influences China’s nuclear planning. Yet, until at least 2019, China’s decisions to continue its nuclear strategy had been decoupled from its decisions to change its conventional military strategy.36 PLA leaders promulgated a new generation of operational regulations in November 2020, which might have created an opportunity to address this decoupling. Yet, there is little evidence to support the possibility of tighter integration of China’s nuclear and conventional strategy, planning, or force building.

China’s nuclear modernization also could reflect the first steps toward a posture that would embrace the first use of nuclear weapons in a conventional conflict. U.S. experts warned that “Chinese theater nuclear forces could…giv[e] Beijing the ability to make limited nuclear threats at the outset of a conflict with the aim of preventing, postponing, or severely limiting any U.S. military intervention.”37 Although China’s nuclear modernization program enables it to more credibly threaten nuclear first use if it chose to abandon its no-first-use policy at any point, its arsenal has some way to go before it is optimized for this goal.

Embrace of a first-use nuclear posture would be a significant departure from China’s existing retaliatory posture. It would indicate a change in how the country has pursued coercive leverage in conventional wars since the end of the Cold War. China has relied on cyberattacks, counterspace weapons, and precision conventional missiles for coercive leverage as a substitute for a nuclear first-use posture. This “strategic substitution” approach, however, was a gamble, and no other nuclear-armed state has adopted it. China took this approach because it did not think that threats of using nuclear weapons first were credible under conditions of mutual nuclear vulnerability and because it lacked the conventional military power to achieve its war aims without some additional source of coercive leverage.

If China were to rely instead on a nuclear first-use posture for coercive leverage, either its assessments of the credibility of nuclear threats would have to increase or its confidence in its current strategic substitutes would have to plummet. China’s approach to gaining coercive leverage was built on an assumption that the United States would be unlikely to use nuclear weapons first in a conflict with China. In the context of a changing conventional military balance in East Asia, the last two U.S. NPRs have called that assumption into question. Although this change could undermine China’s confidence in its current approach, it also could prompt Beijing to pursue a stronger nuclear shield and a better capability for limited nuclear retaliation to deter U.S. nuclear use in response to China’s strategic use of its counterspace weapons, cyberattacks, and precision conventional missiles.

Leaders and Advisers

Whether China seeks a larger, more sophisticated nuclear arsenal to better secure its second-strike capability or to pursue new goals, its nuclear modernization raises questions about whether the views of its decision-makers or its nuclear decision-making process has changed. The top leader’s views about the appropriate role of nuclear weapons have been the most important variable determining China’s nuclear posture since 1964.38 Hence, Xi would have had to approve changes to China’s nuclear forces. One Chinese scholar hinted at Xi’s personal involvement in nuclear modernization decisions when he wrote that, “to adapt to the changing circumstances in international security, President Xi Jinping personally (qinzi) planned and prepared the building of strategic forces.”39 It remains unclear how and why Xi believes that a stronger nuclear force will better equip China to confront those changing circumstances, whether as instruments of political leverage in a peacetime great-power competition or as coercive leverage in a crisis or conflict.

It is also likely that the relative influence of different organizations over China’s nuclear decisions has shifted. The missile force might have gained more influence over nuclear strategy when the Second Artillery was elevated to a full service and renamed the PLARF at the end of 2015. PLA experts have advocated for better theater nuclear capabilities, a launch-on-warning status, and a triad of delivery systems since the 1990s,40 but their proposals previously fell on deaf ears among civilian decision-makers. On the other hand, Chinese nuclear scientists and missile engineers, who historically have had much more influence over nuclear strategy, have seen their influence diluted in the past two decades. They tend to be China’s strongest advocates of restrained nuclear policies such as no first use and arms control. In addition, one Chinese expert wrote in 2021 that Chinese nuclear policy experts “appear cut out of internal policy deliberations.”41 As such, there is some evidence to suggest that a different and possibly narrower set of views are shaping China’s ongoing nuclear modernization decisions.

The Challenges of Ambiguity

More research is needed to unpack the goals and motivations for China’s nuclear modernization. Until both are better understood, the United States should avoid the temptation to assume the worst about China’s motivations and proceed with caution in its policy responses to avoid a self-fulfilling prophecy. If China has yet to decide to shift to a launch-on-warning alert status; arm cruise, hypersonic, and short-range ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads; restart fissile material production; field an orbital bombardment system; or adopt an operational doctrine envisaging limited nuclear war-fighting, it is in the U.S. interest for China not to take these steps toward an arms race, first-use posture, or more accident-prone alert status.

The ambiguity surrounding the goals and motivations of China’s nuclear modernization poses challenges for Beijing too. China’s goal simply still may be fielding a more robust nuclear deterrent sufficient to counter improving U.S. counterforce capabilities. If so, China is no longer implementing that goal with the same discipline and restraint that it displayed in the past. By deploying delivery systems that are not particularly survivable or well suited for first use, such as missiles silos and nonstealthy bomber aircraft, China risks fielding an arsenal that is not entirely consistent with its goal. A nuclear modernization effort that lacks discipline and restraint may open the door for China to adopt other nuclear goals in the future. At the moment, it sends mixed signals to adversaries, who are more likely to pay attention to the most threatening aspects of China’s growing arsenal rather than its remaining gaps and weaknesses.

ENDNOTES

1. M. Taylor Fravel, Active Defense: China’s Military Strategy Since 1949 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019), pp. 243-246.

2. Some of the proposed exceptions to China’s no-first-use policy included a scenario involving Taiwan, because cross-strait affairs are framed as domestic politics in China; if China were suffering sustained air raids threatening the survival of the state; or if China’s arsenal were damaged by U.S. conventional capabilities. See M. Taylor Fravel and Evan S. Medeiros, “China’s Search for Assured Retaliation: The Evolution of Chinese Nuclear Strategy and Force Posture,” International Security, Vol. 35, No. 2 (Fall 2010): 80; Michael S. Chase, Andrew S. Erickson, and Christopher Yeaw, “Chinese Theater and Strategic Missile Force Modernization and Its Implications for the United States,” Journal of Strategic Studies, Vol. 32, No. 1 (2009): 67-114; Evan S. Medeiros, “‘Minding the Gap’: Assessing the Trajectory of the PLA’s Second Artillery,” in Right-Sizing the People’s Liberation Army: Exploring the Contours of China’s Military, ed. Roy Kamphausen and Andrew Scobell (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute and Army War College Press, 2007), pp. 143-190.

3. Fiona S. Cunningham, “Strategic Substitution: China’s Search for Coercive Leverage in the Information Age,” International Security, Vol. 47, No. 1 (Summer 2022): 46-92.

4. Xiao Tianliang, ed., Zhanlue Xue [The science of military strategy] (Beijing: Guofang Daxue Chubanshe [National Defense University Press], 2020), pp. 383-387, translation by author.

5. Fiona S. Cunningham, “Nuclear Command, Control, and Communications Systems of the People’s Republic of China,” Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability, July 18, 2019, https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-special-reports/nuclear-command-control-and-communications-systems-of-the-peoples-republic-of-china/?view=pdf.

6. Mark A. Stokes, “China’s Nuclear Warhead Storage and Handling System,” Project 2049 Institute, March 12, 2010, https://project2049.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/chinas_nuclear_warhead_storage_and

_handling_system.pdf. Open sources were silent on the command and control arrangements for China’s ballistic missile submarine force.

7. U.S. Department of Defense, “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, 2022,” 2022, pp. 97-98, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Nov/29/2003122279/-1/-1/1/2022-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF (hereinafter 2022 China report to Congress).

8. Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, and Eliana Reynolds, “Chinese Nuclear Weapons, 2023,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol. 79, No. 2 (March 4, 2023): 108, https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2023.2178713.

9. Zhang Qiang, “‘Dongfeng-41’ Bufen Jishu Chaoguo Mei’E " [Parts of the ‘Dongfeng-41’ technology surpass the United States and Russia], Keji Ribao [Science and Technology Daily], November 23, 2017, translation by author.

10. Zhang Qiang, “Dongfeng-26 Jinru Huojian Jun Zhandou Xulie: Fanying Kuai Daji Zhunshe Yuancheng [The DF-26 enters the Rocket Force order of battle: Reflecting rapid strike, precision launch and long range], Keji Ribao [Science and Technology Daily], April 27, 2018, https://www.chinanews.com.cn/mil/2018/04-27/8501149.shtml., translation by author. The conventional variant of the DF-21 had an estimated circular error probability of 40 meters.

11. U.S. Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, 2021,” 2021, p. 91, https://media.defense.gov/2021/Nov/03/2002885874/-1/-1/0/2021-CMPR-FINAL.PDF.

12. These units are also known as “equipment inspection regiments” (zhuangjian tuan). David C. Logan and Phillip C. Saunders, “Discerning the Drivers of China’s Evolving Nuclear Forces: Explanatory Models, Observable Indicators, and New Data,” China Strategic Perspectives, No. 18 (forthcoming).

13. 2022 China report to Congress, p. 99.

14. I thank Owen Coté Jr. for this point.

15. Xiao, Zhanlue Xue [The science of military strategy], 2020, p. 388; Xiao Tianliang, ed., Zhanlue Xue [The science of military strategy] (Beijing: Guofang Daxue Chubanshe [National Defense University Press, 2015), p. 368, translation by author.

16. Henrik Stålhane Hiim, M. Taylor Fravel, and Magnus Langset Trøan, “The Dynamics of an Entangled Security Dilemma: China’s Changing Nuclear Posture,” International Security, Vol. 47, No. 4 (2023): 170-171.

17. Owen R. Coté Jr., “Invisible Nuclear-Armed Submarines, or Transparent Oceans? Are Ballistic Missile Submarines Still the Best Deterrent for the United States?” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol. 75, No. 1 (January 2, 2019): 30-35; Minnie Chan, “China’s New Nuclear Submarines Have Missiles That Can Hit More of US: Analysts,” South China Morning Post, May 2, 2021; Kristensen, Korda, and Reynolds, “Chinese Nuclear Weapons, 2023,” p. 125.

18. Zhang, “Dongfeng-26 Jinru Huojian Jun Zhandou Xulie [The DF-26 enters the Rocket Force order of battle],” translation by author.

19. David C. Logan, “Are They Reading Schelling in Beijing? The Dimensions, Drivers, and Risks of Nuclear-Conventional Entanglement in China,” Journal of Strategic Studies, Vol. 46, No. 1 (2023): 5-55.

20. Xiao, Zhanlue Xue [The science of military strategy], 2015, p. 362; Xiao, Zhanlue Xue [The science of military strategy, 2020, p. 383, translation by author.

21. “Under Secretary Bonnie Jenkins’ Remarks: Nuclear Arms Control: A New Era?” U.S. Department of State, September 6, 2021, https://www.state.gov/under-secretary-bonnie-jenkins-remarks-nuclear-arms-control-a-new-era/.

22. U.S. Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, 2021,” pp. 87-88.]

23. Eric Heginbotham et al., “The U.S.-China Military Scorecard,” RAND Corp., 2015, p. 314.

24. Charles L. Glaser and Steve Fetter, “Should the United States Reject MAD? Damage Limitation and U.S. Nuclear Strategy Toward China,” International Security, Vol. 41, No. 1 (Summer 2016): 79.

25. Wu Riqiang, “Living With Uncertainty: Modeling China’s Nuclear Survivability,” International Security, Vol. 44, No. 4 (Spring 2020): 86.

26. Kristensen, Korda, and Reynolds, “Chinese Nuclear Weapons, 2023,” p. 124; 2022 China report to Congress, p. 167.

27. Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris, “Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2015,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol. 71, No. 4 (2015): 78; 2022 China report to Congress, p. 65; Kristensen, Korda, and Reynolds, “Chinese Nuclear Weapons, 2023,” p. 119.

28. Fiona S. Cunningham and M. Taylor Fravel, “Assuring Assured Retaliation: China’s Nuclear Strategy and U.S.-China Strategic Stability,” International Security, Vol. 40, No. 2 (Fall 2015): 7-50.

29. Wu Riqiang, “Xinban ‘Daodan Fangyu Shenyi Baogao’: Touchu Yizhi Buzhu de Chongdong" [The new edition of the ‘Missile Defense Review Report’: The urge to penetrate through continuous restraints], Shijie Zhishi [World affairs], No. 4 (2019), pp. 50-51, translation by author.

30. Liu Chong, “Mei ‘He Taishi Pinggu Baogao’ Chuandi Xiaoji Xinhao" [The U.S. ‘Nuclear Posture Review Report’ sends a negative signal], China.com, February 6, 2018, http://opinion.china.com.cn/opinion_21_178621.html; Lu Yin, Zhanlue Wending: Lilun Yu Shijian Wenti Yanjiu [Strategic stability: Concept and practice] (Beijing: Shishi Chubanshe [Current Affairs press], 2021), pp. 158-162, translation by author.

31. Hiim, Fravel, and Trøan, “Dynamics of an Entangled Security Dilemma.”

32. Glaser and Fetter, “Should the United States Reject MAD?”

33. Fiona S. Cunningham and M. Taylor Fravel, “Dangerous Confidence? Chinese Views of Nuclear Escalation,” International Security, Vol. 44, No. 2 (2019): 61-109.

34. Hiim, Fravel, and Trøan, “Dynamics of an Entangled Security Dilemma," pp. 172-173.

35. Abraham M. Denmark and Caitlin Talmadge, “Why China Wants More and Better Nukes,” Foreign Affairs, November 19, 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2021-11-19/why-china-wants-more-and-better-nukes.

36. Fravel, Active Defense, ch. 8.

37. Evan Braden Montgomery and Toshi Yoshihara, “The Real Challenge of China’s Nuclear Modernization,” The Washington Quarterly, Vol. 45, No. 4 (2022): 47.

38. Fravel and Medeiros, “China’s Search for Assured Retaliation.”

39. Guo Xiaobing, “Changdao ‘lixing, Xietiao, Bingjin’ He Anquanguan Wanshan He Anquan Zhili Tixi" [Proposing a 'rational, collaborative, and progressive’ view of nuclear security, improving the nuclear security governance system], China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations, October 24, 2022, http://www.cicir.ac.cn/NEW/opinion.html?id=1b1d9862-3098-4596-9fad-d48811e40861, translation by author.

40. Alastair Iain Johnston, “China’s New ‘Old Thinking’: The Concept of Limited Deterrence,” International Security, Vol. 20, No. 3 (Winter 1995/96): 5-42.

41. Tong Zhao, “China’s Silence on Nuclear Arms Buildup Fuels Speculation on Motives,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, November 12, 2021, https://thebulletin.org/2021/11/chinas-silence-on-nuclear-arms-buildup-fuels-speculation-on-motives/.

Fiona S. Cunningham is an assistant professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania and a nonresident scholar in the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. This article is based on a paper prepared for a workshop of the Director’s Strategic Resilience Initiative, Los Alamos National Laboratory, in March-April 2022.