“Right after I graduated, I interned with the Arms Control Association. It was terrific.”

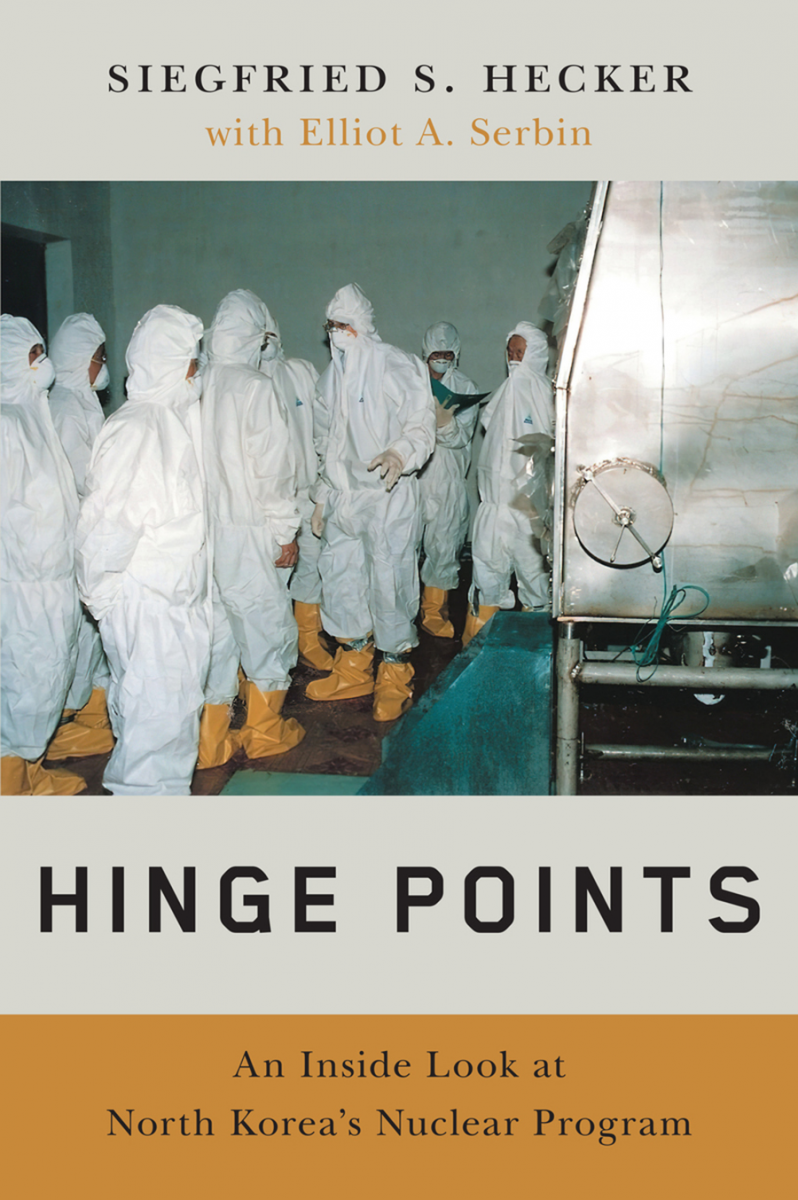

Hinge Points: An Inside Look at North Korea’s Nuclear Program

June 2023

Missed Opportunities With North Korea

Hinge Points: An Inside Look at North Korea’s Nuclear Program

Hinge Points: An Inside Look at North Korea’s Nuclear Program

By Siegfried S. Hecker

Stanford University Press

2023

Reviewed by Sharon Squassoni

The 70th anniversary of the alliance between South Korea and the United States this spring provided a much-needed opportunity to underline the two countries’ solidarity and commitment to peace and security in Northeast Asia. North Korea’s unrelenting missile tests and China’s awkward support for Russian sabotage of the so-called international order undoubtedly have made South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol nervous. His own plan to rein in North Korea, the boldly named Audacious Plan, was rejected summarily last year by Kim Yo Jong, sister of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un.

Anyone hoping for creative new ideas on reducing the threat from North Korea at the White House summit in April between Yoon and U.S. President Joe Biden was disappointed. That, however, was not really the point. The Washington Declaration that the two leaders announced in the Rose Garden on April 26 was all about ally reassurance. For months, South Korean policy elites had been taking the temperature in Washington on nuclear options to improve regional security. Between two disastrous and, one hopes, impossible options—the return of U.S. nuclear weapons to South Korea or the development of an indigenous South Korean nuclear arsenal—lay a less offensive approach to create a NATO-like nuclear-sharing arrangement.

It is this third option that unwisely forms the basis of the declaration. Although there is no mention of NATO in the text, the announced creation of a Nuclear Consultative Group is clearly a nod to NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group. The problem is that NATO nuclear-sharing arrangements involve weapons that are stationed on European soil, whereas South Korea has not hosted U.S. nuclear weapons on its soil since 1991, when the United States withdrew nonstrategic nuclear weapons in response to the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The declaration refers specifically to South Korean “conventional support to U.S. nuclear operations in a contingency” and to improved “combined exercises and training activities on the application of nuclear deterrence on the Korean peninsula.” Yoon, in a speech at Harvard University later in the week, called the declaration “an inevitable choice” and suggested that the new bilateral arrangement would be more effective than NATO nuclear weapon-sharing agreements.

Despite this, it is more than likely that South Korea walked away with less in the declaration than it had hoped. The declaration specified that the “U.S. commitment to extended deterrence to [South Korea] is backed by the full range of U.S. capabilities, including nuclear.” Explicit mention of U.S. nuclear capabilities now seems necessary, given the flurry of protests in Asia when the Biden administration seemed to waver last year about whether it would respond to Russian nuclear use with nuclear weapons. On a positive note, South Korea reiterated its commitment to the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), even if it did not extol the security virtues of forswearing nuclear weapons.

Yoon’s postsummit remarks hinted at his frustrations. He confidently told the audience that, of course, South Korea could make nuclear weapons if it so chose. “However, nuclear weapons are not just a matter of technology. There are complex politics and economics and political and economic equations related to nuclear weapons,” he said. “There are various values and interests that must be given up when possessing nuclear weapons.” Yoon clearly understands that his choice was between his own nuclear weapons and the U.S.-South Korean alliance, but it is damning that the solution is to renuclearize extended deterrence when the United States has committed repeatedly to reducing reliance on nuclear weapons.

The message that only nuclear weapons bring security is not one that will be lost on Kim Jong Un. Although Yoon may be forgoing his own nuclear weapons now in favor of closer planning with Washington on U.S. nuclear deterrence, the extended deterrence equation always fails to eliminate nuclear weapons as a reasonable recourse.

To longtime observers, the Biden-Yoon summit is the latest chapter in decades of ineffectual policies to reduce the nuclear threat from North Korea. Isolating, berating, and belittling North Korea, in combination with ostentatious displays of U.S. nuclear might, have rarely caused the hermit kingdom to cease its provocative actions. There is no reason why South Korea and the United States would believe the latest actions outlined in the Washington Declaration would be effective. They are a temporary measure aimed more at dampening South Korea’s domestic debate rather than encouraging North Korean cooperation.

Discerning why and how North Korea has made choices to roll back, freeze, or accelerate its nuclear arsenal development is particularly tough. Thankfully, John Lewis, a Stanford University professor who played a leading role in facilitating dialogue with North Korea, recruited Siegfried Hecker, a former director of Los Alamos National Laboratory, to travel multiple times to North Korea to engage in discussions with technical and political officials and to visit key nuclear sites. Hecker’s first trip took place in 2004, and he traveled nearly every year to North Korea until 2010. His experiences and analysis are captured engagingly in this book.

Discerning why and how North Korea has made choices to roll back, freeze, or accelerate its nuclear arsenal development is particularly tough. Thankfully, John Lewis, a Stanford University professor who played a leading role in facilitating dialogue with North Korea, recruited Siegfried Hecker, a former director of Los Alamos National Laboratory, to travel multiple times to North Korea to engage in discussions with technical and political officials and to visit key nuclear sites. Hecker’s first trip took place in 2004, and he traveled nearly every year to North Korea until 2010. His experiences and analysis are captured engagingly in this book.

An unwilling recruit at first, Hecker had planned to spend his retirement on topics on which he was more expert, collaborating as best he could with Russian scientists in cooperative threat reduction initiatives and building ties with Chinese nuclear weapons scientists to improve nuclear security. He certainly had his share of “nuclear tourism” in far-flung places, including Russia’s nuclear test site in Semipalatinsk, Kazakhstan, where he discovered that the Russians had left intact nuclear devices in testing shafts. Inordinately modest, Hecker has produced a masterful analysis not just of the policy debates, decisions, and mistakes that have produced a standoff with North Korea, but also of the technical dilemmas faced in North Korea’s nuclear weapons program and in the United States’ own expectations and analysis of the North’s achievements.

Hecker argues that there were at least six hinge points in the last 20 years when outcomes could have been vastly different if different choices had been made. His underlying assumption is that the North Koreans have always pursued a dual-track approach: developing nuclear weapons for security and negotiating them away for economic and security gains. This analysis assumes that, with the right incentives, cooperation is possible.

The first hinge point occurred in October 2002, when the Bush administration torpedoed the 1994 Agreed Framework, a deal to provide light-water reactors and heavy fuel oil in exchange for North Korea’s shutdown of its plutonium-production reactor and reprocessing plant. Rather than working through the agreement to resolve compliance issues, the Bush administration effectively shattered the deal, triggering North Korea’s withdrawal from the NPT. The second hinge point occurred in September 2005 when the Bush administration undermined the joint statement agreed during the six-party talks, and a third fateful decision came when the Obama administration walked away from the Leap Day deal in response to a North Korean satellite launch.

In January 2015, the Obama administration failed to take North Korea’s proposed nuclear testing moratorium seriously, after which the North Koreans conducted three more nuclear tests. In February 2019, President Donald Trump literally walked away from the Hanoi summit with Kim because the two sides failed to agree on what might be captured in the definition of North Korea’s Yongbyon nuclear facility. There are many more missteps in U.S. policymaking, but Hecker identifies these as the major ones and highlights how the North Korean nuclear weapons program benefited in their aftermath. At one point, he suggests that, “History will not be kind to Washington.”

A metallurgist by training, Hecker was perhaps the perfect interlocutor to discuss Pyongyang’s then-plutonium-based nuclear weapons program. As a career government scientist working on nuclear weapons, however, he also was aware of the security risks of his travel to North Korea. Surprised at first that he was given permission to travel, he meticulously documented his discussions and briefed government officials and nongovernmental experts before and after his trips.

This is the fundamental value of such Track 2 meetings, which is to gather and impart information to governments when direct, official meetings between governments are difficult if not impossible to convene. One of the more interesting elements of the book is Hecker’s interactions with Chinese nuclear weapons scientists on the margins of those North Korea trips; it clearly must have been invaluable to compare notes with foreign scientists who likely had close connections to North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. Overall, the reader cannot fail to be impressed by Hecker’s devotion long after retirement to public service.

For consumers of policy memoirs, Hinge Points may seem disarmingly candid. Referring to the chief U.S. demand of North Korea, Hecker suggests at one point that “no one quite knew what ‘denuclearization’ even meant.” Unfortunately, this is probably still true today, despite the reams of official papers devoted to denuclearization road maps.

Unlike other physical scientists who have turned their hands to policy, Hecker understands the complexities without trying to reduce them to simple solutions. His frustration at the lack of progress with North Korea is palpable and a refreshing contrast to the tired cynicism of experts in Washington who believe that Pyongyang is a hopeless case yet refuse to adopt different approaches. One can only hope Hecker has another chance to visit North Korea to brighten the prospects for diplomacy.

Nuclear expert Sharon Squassoni is a research professor at The George Washington University and co-chair of the Science and Security Board and ex officio member of the Governing Board at the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.