Volume 14, Issue 7

October 26, 2022

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February, the United States indefinitely suspended the U.S.-Russian Strategic Stability Dialogue, a longstanding forum in which the two sides planned to lay the groundwork for more formal bilateral talks on a successor to the only current but soon-expiring nuclear arms control agreement between them: the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START).

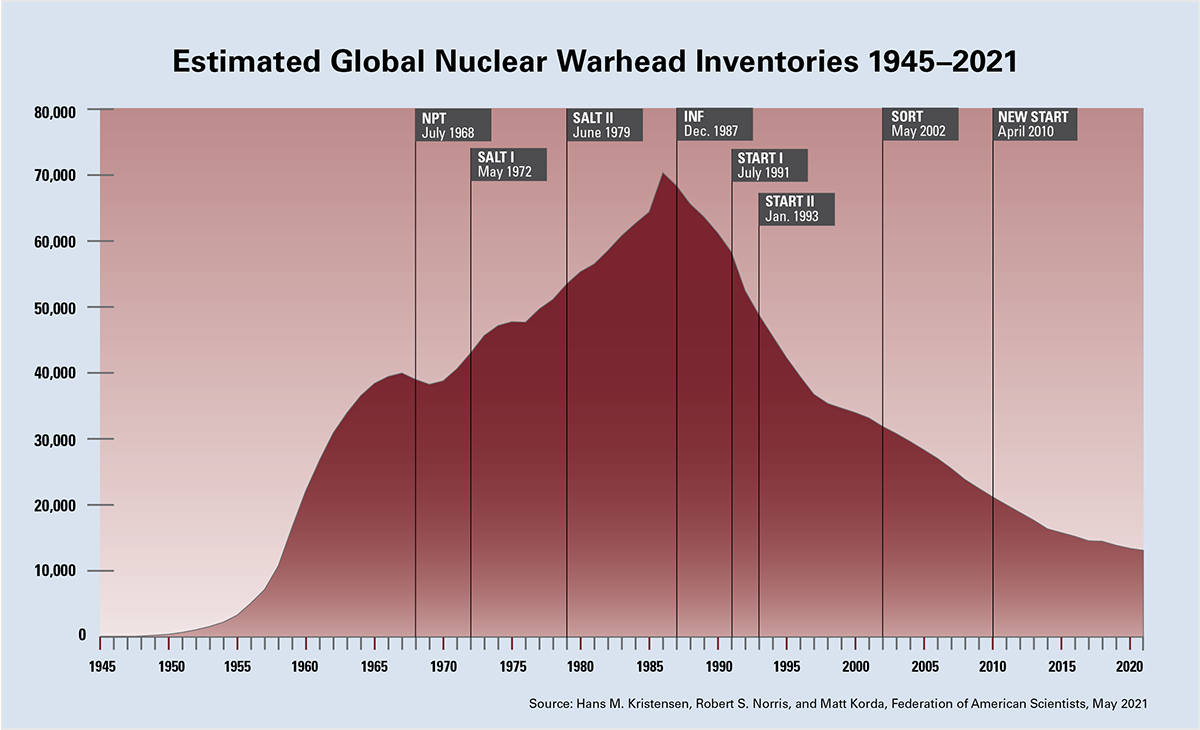

This is certainly not the first time throughout the long history of U.S.-Russian dialogue on arms control, disarmament, and risk reduction that talks between the world’s two largest nuclear-armed states have come to a standstill. Nevertheless, for more than five decades, leaders in both countries have overcome vast ideological and geopolitical differences and disputes to, out of a shared recognition of the great dangers of nuclear weapons, establish and maintain mutually verifiable limits on their respective nuclear arsenals. Since the first two agreements struck in 1972, the United States and Russia (and the former Soviet Union) have negotiated a series of nuclear arms control and arms reduction agreements that have successfully strengthened strategic stability, provided highly-valued predictability, and reduced the risk of nuclear war.

In support of such benefits of arms control, U.S. President Joseph Biden and Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed last year to extend New START, as allowed by the treaty text, until Feb. 5, 2026. As a result, the United States and Russia have continued to adhere to the limitations on their nuclear arsenals under New START, with the most recent regular biannual exchange conducted on Sept. 1.

At the same time, however, Putin continues to warn of potential Russian nuclear weapon use as a response to any perceived interference in Ukraine, existential threat to Russia, or threat to what the federation calls its “territorial integrity,” which includes the four recently illegally annexed Ukrainian regions. Although the likelihood of nuclear use remains low, the United States and its allies and partners must meet nuclear threats with utmost seriousness, condemnation, and consequence.

Even while rallying the world in support of Ukraine’s defense against Russia’s invasion and ongoing attacks, Washington must pursue the negotiation of a new arms control arrangement to supersede New START sooner rather than later.

“No matter what else is happening in the world,” said Biden on Sept. 21, “the United States is ready to pursue critical arms control measures.”

Despite such statements from Biden, as well as senior Russian officials, arms control talks have not begun, in part due to ongoing differences over how and when to resume New START on-site inspections, which have been paused since 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic as well as Russian implementation concerns. Even if such talks began soon, the time left until 2026 is not much for the two countries to hold formal, time-consuming treaty negotiations and secure any necessary domestic support for the new arrangement.

If the treaty should expire in 2026 with no replacement, it would mark the first time since 1972 that the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals are entirely unconstrained.

In addition, Russia’s catastrophic war in Ukraine has vastly exacerbated uncertainty on what, if any, arms control arrangement may follow New START.

Putin’s war of choice on Ukraine is absolutely indefensible and reprehensible, and Russia has rightly been hit with very real consequences from countries across the world. The pursuit of formal arms control negotiations with Moscow nonetheless is necessary, if only to ensure that the Russian nuclear arsenal remains constrained, subject to a verification regime, and open to a measure of transparency. The alternative in which the two sides fail to negotiate a new nuclear arms control framework will only heighten the factors leading to strategic instability and nuclear war, exacerbate the difficulties of engaging China and other nuclear-armed states in the nuclear risk reduction and disarmament enterprise, and open the door for a global nuclear arms race that benefits no one.

Now is the time to evaluate the potential approaches to the creation of a new nuclear arms control framework.

The Value and Status of New START

The last major nuclear arms control negotiation between Washington and Moscow took place more than a decade ago. After 11 months of negotiations—a historically rather short timeline for striking arms control deals—U.S. President Barack Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev signed New START in April 2010.

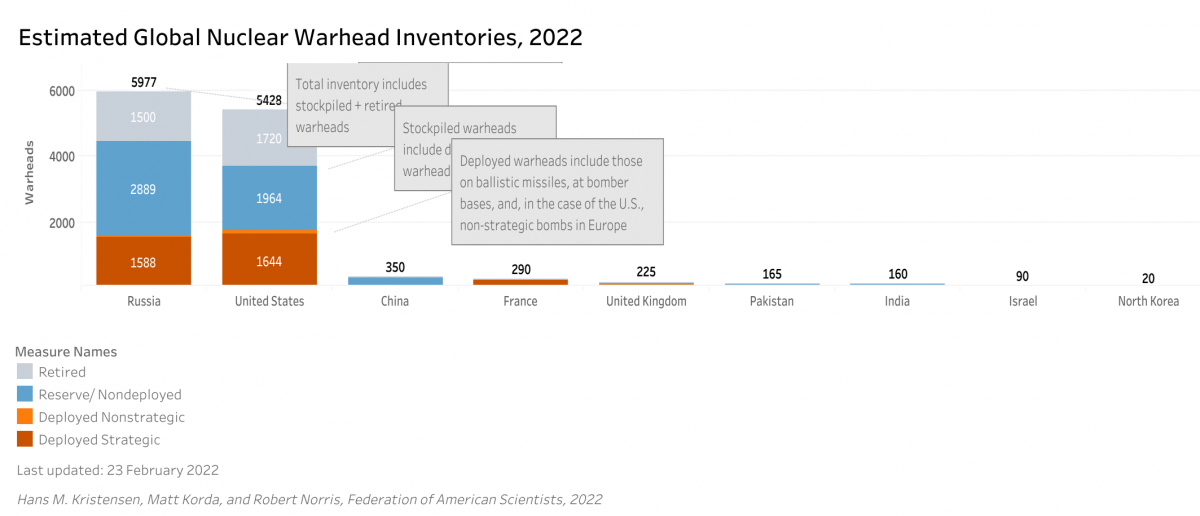

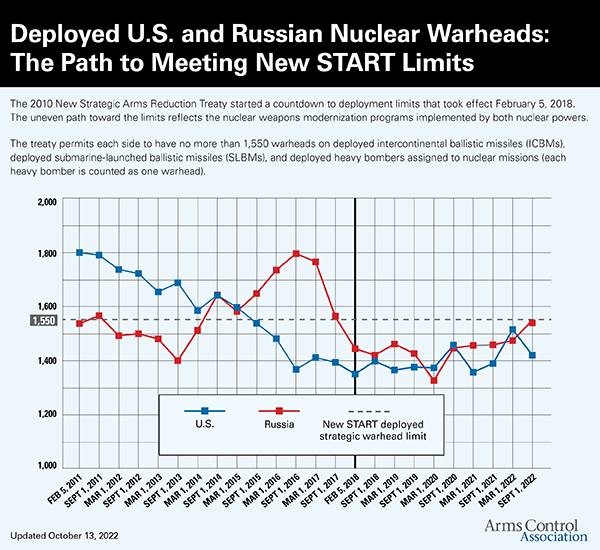

The treaty limits U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear arsenals to 1,550 warheads deployed on 700 delivery vehicles, including intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), sea-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and heavy bombers assigned to a nuclear mission.

New START entered into force in February 2011 with an expiration date of 10 years, though it could be extended for an additional five years upon mutual agreement. Washington and Moscow had until February 2018 to cut their respective nuclear arsenals to those limits, and they successfully did so, with Russia significantly reducing its number of deployed warheads on ballistic missiles.

New START entered into force in February 2011 with an expiration date of 10 years, though it could be extended for an additional five years upon mutual agreement. Washington and Moscow had until February 2018 to cut their respective nuclear arsenals to those limits, and they successfully did so, with Russia significantly reducing its number of deployed warheads on ballistic missiles.

Over the ensuing years, the U.S. and Russian arsenals would naturally fluctuate based on the particular maintenance and upgrade schedules for the nuclear weapons components. Washington and Moscow have both remained at or below the treaty limits since 2018. Following the demise of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty in 2019, New START became the last treaty limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals.

An integral part of New START has been the establishment of a rigorous verification regime.

The treaty allows 18 on-site inspections per country per year and requires regular notifications on the status of strategic delivery vehicles and launchers, data exchanges twice a year on the makeup of each country’s strategic nuclear arsenal, as well as the formation of the Bilateral Consultative Commission (BCC) to handle any compliance or implementation concerns that might arise.

This regime provides crucial, detailed information about the strategic nuclear arsenals of the world’s top two owners of nuclear weapons that cannot currently be gained through another avenue. The U.S. Defense Department has gone on the record emphasizing the great value it places on the information about Russia’s nuclear arsenal gathered due to New START.

Former and then-current government and military officials as well as national security leaders also spoke out strongly in favor of extending New START by five years until 2026, which Biden and Putin agreed to do in February 2021, just two days before the treaty’s expiration.

The pandemic disrupted business as usual when it came to both the New START verification regime and the talks on an arms control arrangement to follow the treaty after its expiration—all of which Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has further disrupted as well as imperiled.

The United States and Russia mutually decided to suspend on-site inspections, as well as indefinitely delay a meeting of the BCC, in March 2020 as the coronavirus tore across the world. The two countries started to hammer out how to restart inspections about a year ago. However, Moscow informed Washington in August 2022 of its decision to temporarily prohibit inspections of its nuclear weapons-related facilities subject to New START.

The Russian Foreign Ministry has claimed that there are ongoing unresolved issues, including adjusted inspection procedures to account for situations in which coronavirus spreads among the crews and inspectors, as well as difficulties the Russian flight crew and inspectors have encountered when trying to obtain visas and permissions to enter airspace controlled by the United States and its allies and partners. The latter has occurred primarily as the United States and its allies and partners, such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), have imposed steep costs on Russia for its invasion of Ukraine.

Russia’s announcement regarding inspections came during the second week of the monthlong review conference for the 1968 nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), which brought together leaders from nuclear and non-nuclear weapon states at the United Nations headquarters in New York City.

Biden and Putin released statements on the first day of the conference Aug. 1, in which they each emphasized their commitment to nuclear arms control, disarmament, and nonproliferation.

The United States and Russia were already going to be on the hot seat at the conference due to a widespread view among NPT states-parties that the two countries, along with the other three NPT-recognized nuclear-weapon states (China, France, and the United Kingdom), have not upheld their treaty obligation to genuinely pursue nuclear disarmament.

With New START expiring in less than four years and no replacement arms control arrangement in sight, plus the more than two-year ongoing break in on-site inspections, Washington and Moscow have little ground to stand on to say that they have been fulfilling their NPT commitments since the last review conference in 2015.

The Current Generation of Security Concerns

For years, the United States and Russia have been suggesting differing agendas on what to cover in the next arms control arrangement after New START. The road to future U.S.-Russian arms control has long been forecast to be divisive and arduous, as well as reliant on political will.

After New START’s official extension in 2021, the Biden administration began to broadly outline its priorities for what might come next, particularly aiming to limit for the first time Russian non-strategic, or tactical, nuclear weapons. Moscow is estimated to have about 1,900 tactical nuclear weapons, all in central storage.

In addition, Washington wants to incorporate new Russian nuclear weapon delivery systems, such as those officially unveiled by Putin in 2018 and 2019 like the nuclear-powered, nuclear-tipped torpedo named Poseidon, and to explore options for arms control with China.

In contrast to the Trump administration’s initial effort to condition the extension of New START on establishing some sort of future U.S.-Russian-Chinese arms control arrangement, the Biden administration has taken a different approach toward conducting arms control talks with Beijing by suggesting bilateral U.S.-Chinese talks.

The current U.S. approach toward China on arms control, though requiring increased attention by the Biden administration, makes sense for two reasons. First, Beijing has yet to engage in the kind of nuclear arms control and disarmament treaties signed by Washington and Moscow, which struck their first arms control deal in 1972. It would be difficult for China to jump into an ongoing arms control process, outside Beijing’s preferred multilateral arena, with which the United States and Russia have much more established, though strained, relations on the issue.

Second, the Chinese nuclear weapons arsenal is estimated to be at 350, which is significantly smaller than the U.S. nuclear arsenal of about 4,000 and the Russian arsenal of about 4,500. Even if Beijing continues with the rapid expansion of its arsenal to amass 700 strategic nuclear warheads by 2027 and 1,000 by 2030 as projected by the Pentagon, it will still be numerically smaller than those of the United States and Russia. An arms control arrangement that requires equal numerical limits on all parties, like New START, would therefore be a non-starter for China.

Beijing has repeatedly expressed adamant resistance to engaging in bilateral or trilateral arms control talks over the years, instead stating its preference for multilateral arms control and stipulating that its involvement depends on U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals first decreasing to the size of the Chinese arsenal. By setting realistic expectations with China, Washington may be able to see some long-sought-after progress, which may look as straightforward as formally establishing a bilateral strategic stability dialogue.

In addition, a concern repeatedly popping up in U.S.-Russian dialogue would be addressed for the time being with a U.S.-Chinese strategic stability dialogue underway, which can ideally be paired with efforts in other fora as well. In other words, Russia’s common refrain to the U.S. demand to include China in any future arms control arrangement is to require the participation of France and the United Kingdom as well. By addressing other nuclear powers in alternative venues, such as in a separate bilateral dialogue or in the P5 process, and essentially dividing the multitude of contentious issues on the table into different, though parallel, strains, Washington and Moscow could make some headway bilaterally.

Russia also brings to the table concerns with U.S. missile defenses, which Washington has long resisted putting up for negotiation, and U.S. non-strategic weapons deployed in Europe, estimated at about 100. Since the demise of the INF Treaty in 2019, Moscow has aimed to address at least a portion of the missiles formerly banned by this accord (ground-launched nuclear and conventional, ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers) in the next arms control arrangement.

The United States and Russia do share, however, a recognition of the fact that what may follow New START might not be a traditional arms control treaty, but rather another type of arms control arrangement or arrangements. The makeup of the U.S. Senate essentially guarantees the impossibility of procuring advice and consent on the ratification of a new U.S.-Russian arms control treaty. Therefore, the two sides must consider alternative forms of agreement, including an executive agreement.

Russia communicated its agenda to the United States and NATO in two separate proposals for agreements on broader security guarantees delivered to Washington and Brussels in December 2021. The Russian proposals were laden with non-starters (such as a proposed commitment from the United States and NATO to prohibit further NATO expansion), making it apparent that the documents were not ultimately serious in nature and thus intended for rejection.

| Russian Proposals on Security Guarantees to the United States and NATO, Dec. 15, 2021 | U.S. and NATO Responses to Russia, Jan. 26, 2022 |

| Arms Control, Risk Reduction, and Transparency | |

|

Parties shall not deploy ground-launched, intermediate- and short-range missiles either outside their national territories or inside their national territories from which the missiles can strike the national territory of the other party. |

The United States is prepared to begin discussions on arms control for ground-based intermediate- and short-range missiles and their launchers. NATO calls for Russia to engage with the United States on these discussions. The United States is prepared to discuss transparency measures to confirm the absence of Tomahawk cruise missiles at Aegis Ashore sites in Romania and Poland, so long as Russia provides reciprocal transparency measures on two ground-launched missile bases of U.S. choosing in Russia. |

|

No similar articles. |

The United States proposes to begin discussions immediately on follow-on measures to New START, including on how future arms control would cover all U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons (strategic and non-strategic, deployed and non-deployed) and new kinds of nuclear-armed intercontinental-range delivery vehicles. NATO calls for Russia to engage with the United States on these discussions. |

|

NATO calls for all states to recommit to their international arms control, disarmament, and nonproliferation obligations and commitments, such as toward the Chemical Weapons Convention and Biological Weapons Convention. NATO calls for Russia to resume implementation of the Conventional Armed Forces in Europe Treaty. |

|

|

NATO is ready to consult on ways to reduce threats to space systems and to promote a free and peaceful cyberspace. |

|

| Sources: Article 6, Russia Proposal to U.S.; Article 5, Russia Proposal to NATO; Pages 3 and 4, U.S. Response to Russia; Article 9, NATO Response to Russia | |

| Nuclear and Conventional Forces Posture | |

|

Parties shall not deploy nuclear weapons outside their national territories and shall destroy all existing infrastructure for deployment of nuclear weapons outside of their national territories. Parties shall not train military and civilian personnel from non-nuclear countries to use nuclear weapons or conduct exercises that include scenarios involving the use of nuclear weapons. |

The United States and NATO are prepared to discuss areas of disagreement between NATO and Russia on U.S. and NATO force posture, including possibly the deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe, and discuss conventional forces concerns, including enhanced transparency and risk reduction through the Vienna Document. NATO is prepared to discuss holding reciprocal briefings on Russia's and NATO's nuclear policies. |

| Sources: Article 7, Russia Proposal to U.S.; Article 4, Russia Proposal to NATO; Page 3, U.S. Response to Russia; Article 9, NATO Response to Russia | |

| NATO-Russia Relations | |

|

Parties reaffirm that they do not consider each other as adversaries. Parties shall not undertake actions, participate in activities, or implement security measures that undermine the security interests of the other party. Parties shall not use the territories of other states to execute an armed attack against the other party. Parties shall settle all international disputes by peaceful rather than forceful means. Parties shall use fora such as the NATO-Russia Council to address issues or settle problems. Parties shall establish telephone hotlines. |

NATO poses no threat to Russia. NATO believes that tensions and disagreements must be resolved through dialogue and diplomacy, rather than through the threat or use of force. NATO calls for Russia's immediate de-escalation around Ukraine. NATO supports re-establishing NATO and Russian mutual presence in Moscow and Brussels and establishing a civilian telephone hotline. |

| Sources: Articles 1 and 3, Russia Proposal to U.S.; Articles 1, 2, and 3, Russia Proposal to NATO; Articles 1, 2, and 7, NATO Response to Russia | |

| NATO Expansion | |

|

All NATO member states shall commit to prohibit any further NATO expansion, to include denying the accession of Ukraine. The United States shall not establish military bases in or develop bilateral military cooperation with former USSR states who are not part of NATO. |

The United States and NATO are committed to supporting NATO's open door policy. The United States is willing to discuss reciprocal transparency measures and commitments by both the United States and Russia to not deploy offensive ground-launched missile systems and permanent combat forces in Ukraine. |

| Sources: Article 4, Russia Proposal to U.S.; Article 6, Russia Proposal to NATO; Pages 1 and 2, U.S. Response to Russia; Article 8, NATO Response to Russia | |

| Military Maneuvers and Exercises | |

|

Parties shall regularly inform each other about military exercises and main provisions of their military doctrines. Parties shall not deploy armed forces in areas where the deployment could be perceived by the other party as a threat to its national security (except when the deployment is within the national territories of the parties). Parties shall not fly heavy bombers (whether nuclear or non-nuclear) or deploy surface warships in areas outside national airspace and national territorial waters where they can strike targets in the territory of the other party. Parties shall maintain dialogue to prevent dangerous military activities at sea. |

NATO calls for Russia to withdraw its forces from Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova. The United States is prepared to discuss confidence building measures regarding ground-based military exercises in Europe (to include modernization of the Vienna Document) and to explore an enhanced exercise notification regime and nuclear risk reduction measures (including strategic nuclear bomber platforms). The United States and NATO are prepared to explore measures to prevent incidents at sea and in the air (to include discussing enhancements in the Incidents at Sea Agreement and the Vienna Document). |

| Sources: Article 5, Russia Proposal to U.S.; Articles 2, 3, and 7, Russia Proposal to NATO; Pages 2 and 3, U.S. Response to Russia; Articles 8 and 9, NATO Response to Russia | |

| Reaffirmation of UN Charter | |

|

Parties shall ensure that all international organizations or military alliances in which at least one party participates adhere to the principles contained in the United Nations Charter. |

NATO remains committed to the fundamental principles and agreements underpinning European security, including the United Nations Charter. |

| Sources: Article 2, Russia Proposal to U.S.; Article 8, Russia Proposal to NATO; Article 3, NATO Response to Russia | |

Though flawed, pieces of the Russian proposals touch upon concerns that the United States and its allies and partners share, suggesting possible options for future arms control arrangements. For instance, both the proposals to the United States and NATO included an iteration of Moscow’s suggestion for a moratorium on the deployment of INF missiles. Limiting at least some of the missiles once banned by the INF Treaty—which the Pentagon has begun developing but has struggled to lock down basing options for abroad—would benefit the United States by helping to avoid an arms race of INF-like missiles and prevent the reintroduction of additional, unnecessary nuclear capabilities into Europe as well as Asia.

Of course, if not doing so already, the United States will have to grapple with the significant changes in the strategic and geopolitical environment in which the United States and Russia now operate— changes that inescapably affect the realm of arms control. For instance, Moscow has depleted its conventional forces throughout its brutal assault on Ukraine and will therefore have to spend considerable time and money as the war drags on or after the war to rebuild those forces. Consequently, as acknowledged by the Biden administration’s National Security Strategy publicly released Oct. 12, Moscow may funnel most funds toward rebuilding its conventional arsenal and increase reliance on its nuclear deterrent, all while dealing with an expansion of NATO.

Lastly, it is important to note that arms control talks would take place against the backdrop of Putin’s recent and thinly veiled threats to use nuclear weapons several times, including a few days into the renewed Russian invasion of Ukraine and, most recently, after the illegal annexation of four Ukrainian regions.

“We will defend our land with all the forces and resources we have, and we will do everything we can to ensure the safety of our people,” he said on Sept. 30. In late February, he also ordered the move of “Russia’s deterrence forces to a special regime of combat duty.” The scenarios in which Putin may consider nuclear use, most of which Russia outlined in its June 2020 policy, include if any country attempts to interfere in the war on Ukraine, if Moscow perceives a threat to Russia’s existence, or if Moscow perceives a threat to what it calls its “territorial integrity.”

Although the possibility of the actual use of nuclear weapons is low, it is not zero, with some analysts suggesting Russia may use nuclear weapons in a strike at a Ukrainian military facility or in a “nuclear display,” such as the detonation of a nuclear weapon over the Black Sea or the Arctic Ocean. Putin’s nuclear threats must be taken seriously.

There is unquestionable, considerable daylight between the U.S. and Russian agendas for a future arms control arrangement that, considered alongside Putin’s war of choice in Ukraine, portends a rather gloomy outlook for arms control in a post-New START world. However, nuclear arms control remains in the best security and safety interests of both the United States and Russia, not to mention the entire world, especially at such a time of growing nuclear threats and risks of escalation and miscalculation.

Redefining Arms Control in the Current Age

The United States refuses to engage in “arms control for arms control’s sake,” argued Marshall Billingslea, then-special envoy for arms control at the U.S. State Department, in May 2020. At the time, less than a year before New START was set to expire, the Trump administration had yet to put forward a concrete proposal on either the treaty’s extension or an alternative arms control arrangement to supersede the treaty.

When the Trump administration’s proposal did arrive in October 2020, it was a poison pill meant to ensure the expiration of New START with no replacement, a result that arms control opponents such as Billingslea wanted.

In December 2019, Putin tabled an offer to extend the treaty for five years with no preconditions. Ultimately, the Trump administration left the issue of New START extension up to the Biden administration, which agreed in February 2021 to the extension.

Billingslea’s charge served as a common retort to those who wanted to see the treaty extended. The Trump administration had argued that New START “does not reflect today’s reality,” citing how the treaty neither included China nor covered Russian novel and tactical nuclear weapon systems. Extending New START and pursuing those additional arms control objectives, however, were not mutually exclusive. Endeavors to expand the arms control architecture to include additional types of nuclear weapons and additional nuclear-armed countries have an arguably stronger fighting chance without having to simultaneously worry about the dangers of unconstrained U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals.

The overall benefits of arms control, whether undertaken in times of relationship highs or lows, can be many, including avoiding an action-reaction arms race; reducing incentives to preemptively strike adversary conventional and/or nuclear forces; lowering the chances of inadvertent escalation; increasing transparency and predictability; and saving money. In general, arms control can be defined as a form of mutual agreement or commitment through which states aim to reduce nuclear risks.

This definition of arms control is broad, as it should be. Traditionally, the concept of arms control has been primarily thought of as referring to formal treaties imposing specific limits on or the elimination of particular components of U.S. and Russian/Soviet nuclear arsenals. However, with the advent of new and emerging technologies affecting strategic stability, the development and deployment of new nuclear weapon delivery systems (such as Russia’s Poseidon), the advancing abilities of existing nuclear weapon systems (such as the increased maneuverability of ballistic missiles), as well as the high disinclination that the U.S. Senate would support new arms control treaties, the traditional understanding of arms control has warranted a reevaluation.

| U.S.-Russian Nuclear Arms Control Agreements |

Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) (1969-1972)

|

Strategic stability can be affected by a variety of capabilities, whether nuclear or non-nuclear (e.g., conventional weapons as well as cyber operations) and offensive or defensive. Most often, strategic stability is defined as the union of crisis stability, in which nuclear powers are deterred from launching a nuclear first strike against one another, and arms race stability, in which two adversaries do not have an incentive to build up their strategic nuclear forces.

The 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union underscored the interrelationship between defensive and offensive systems by imposing limits on anti-missile systems. At the heart of the treaty, from which Washington withdrew in 2002, stood the recognition that the acquisition of ever-more capable offensive weapons would result in efforts by targeted states to acquire defenses against those weapons, sparking a never-ending cycle of competitive one-upmanship and upending strategic stability.

As another example of this concept, multiple countries are pursuing new classes of hypersonic weapons: hypersonic boost-glide vehicles and hypersonic cruise missiles. The United States is developing conventional-only hypersonics, while China and Russia have also deployed or continued to develop nuclear or dual-capable hypersonics. New hypersonic weapon capabilities have ignited a new arms race among nuclear-armed countries to master this technology first, as well as a drive to develop anti-hypersonic defenses. Furthermore, a 2019 study conducted by United Nations two disarmament bodies found that some countries may perceive certain types of hypersonic weapons as a strategic threat regardless of whether they are conventional- or nuclear-armed.

The new types of hypersonic weapons are but one category of numerous new and emerging technological military capabilities entering the field today and arguably adding new factors to the strategic stability calculation. A sophisticated cyber operation, depending on its intent, can wreck deleterious effects directly on a country’s nuclear weapons arsenal (e.g., nuclear-capable delivery vehicles or the command, control, and communications systems) or indirectly on the confidence and situational awareness of those who decide whether to employ nuclear weapons. Artificial intelligence (AI) generates its own set of risks given the variety of applications that possess a form of cognitive capability and fall beneath the wide AI umbrella; for example, an overreliance on AI-enabled systems could prompt humans to make premature or misguided decisions, leading to armed conflict and possibly nuclear war.

All this to say, arms control must work to integrate all the new and emerging military capabilities and technologies, from nuclear to non-nuclear, capable of making waves in the nuclear realm, as well as take into consideration the various threat perceptions held by nuclear-armed countries. Given the breadth of capabilities and concerns on the table, arms control must encompass a broad range of initiatives, including not only traditional legally binding treaties but also risk reduction, crisis management, and confidence-building measures, such as establishing hotlines between high-brass military officials. Future arms control arrangements must also consider limitations or reductions across different domains (e.g., outer space, cyberspace) and different capabilities (e.g., nuclear delivery vehicles, conventional hypersonic weapons), in a style known as asymmetric arms control.

There are certainly lessons to be learned from past or expiring arms control agreements. New START, for instance, has provided an avenue to address new kinds of strategic offensives arms that might emerge after the treaty entered into force. Yet, as some experts have noted, the next arms control arrangement may aim to require a stronger, more effective new kinds of strategic offensive arms clause, such as one that applies to both nuclear and non-nuclear weapons of strategic range and automatically makes new kinds accountable to the terms of the arrangement.

Arms control at a time like this, when Russia has brandished its nuclear arsenal on multiple occasions during its war in Ukraine, becomes all the more important. Arms control can mean not only limitations on the numbers and the kinds of nuclear weapon systems but also informative data exchanges, boots-on-the-ground inspections at nuclear facilities, and crisis communication channels—all of which shed light on what a country holds in its nuclear arsenal.

The challenge presently facing the Biden administration can be described less as deciding whether arms control is worthwhile and valuable to U.S. national security interests, as it clearly is, and more as determining how to preserve, expand, and advance arms control given the differing U.S. and Russian agendas and, more notably, the despicable war waged in Ukraine by Russia.

Next Steps in U.S.-Russian Arms Control

The crucial questions at this juncture are when the United States and Russia should begin formal arms control negotiations and, relatedly, if the start of those negotiations relies on Ukraine and Russia first reaching some type of peace agreement.

After Russia invaded Ukraine in February, the Biden administration rightly paused the U.S.-Russian Strategic Stability Dialogue. Biden and Putin revived the dialogue in 2021, which then convened in July, September, and January. In the last meeting, Moscow had coopted the dialogue for its own purposes by deviating from the usual established agenda and inserting its demands for security guarantees from Washington and NATO, styled to lay the diplomatic groundwork for its invasion of Ukraine less than two months later. Thus, the bilateral dialogue is no longer a suitable place for genuine arms control discussions at this time. Plus, the dialogue, which covers topics outside of arms control, is not equivalent to a venue for formal arms control negotiations, and the latter is where Washington and Moscow must go.

Launching formal arms control negotiations on a New START replacement as Russia commits more atrocities in Ukraine will take tremendous political will. Yet, given the risks the Russian nuclear arsenal poses, it remains essential that the United States, with support from its allies and partners, engages in serious, nose-to-the-grindstone negotiations with Russia. A Russian nuclear arsenal with no limits or transparency would only heighten the risks of intended or unintended nuclear escalation and miscalculation in areas of conflict, such as Ukraine. Thus, the sooner the better that those negotiations begin.

With this recognition, by the end of 2022 at the absolute latest, there are two actions that Washington and Moscow must accomplish:

- The United States and Russia must launch formal bilateral negotiations on a new arms control arrangement(s) to supersede New START.

- Russia must end its restriction of New START on-site inspections at its nuclear facilities subject to the treaty and cooperate in the resumption of the inspections soon thereafter. However, formal arms control negotiations should not be contingent on the resumption of New START inspections.

During the formal U.S.-Russian arms control negotiations, the following should constitute the main objectives for a New START follow-on arrangement.

Central Limits

The central limits of the new arrangement should further reduce the size of U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear arsenals and incorporate new nuclear weapon capabilities. New START imposes caps on ICBMs, SLBMs, and heavy bombers assigned a nuclear mission, and a new arrangement should maintain restrictions on those capabilities while adding restrictions on new ones, such as Russia’s Poseidon nuclear-powered torpedo. The new arrangement should also more specifically capture intercontinental, ground-launched missiles, for although Russia’s Avangard fell under the treaty due to its pairing with a treaty-accountable delivery vehicle, future systems of this type may not necessarily be covered.

The new limit for strategic nuclear warheads should be lowered from 1,550 to 1,000. In 2013, the Obama administration determined that the U.S. nuclear arsenal could be reduced by up to one-third below the New START level without any ill effects on U.S. national security and nuclear deterrence. Although the strategic environment has changed since then with Russia’s new nuclear delivery systems and China’s expanding nuclear arsenal, so have U.S. nuclear weapon systems advanced in their abilities, meaning that the Pentagon can do more with less. Like-for-like limitations are not particularly helpful in today’s day and age, and the Pentagon’s calculation for what kind of and how many capabilities are needed to meet which threats should be reevaluated.

Furthermore, while the Pentagon projects that Beijing aims to have 1,000 strategic nuclear warheads by 2030, this is ultimately an estimation, and the Pentagon has made enormously wide-ranging projections in the past. Even so, attempts to include China in U.S.-Russian arms control have been met with only failure thus far, which is unlikely to change now. Allowing three nuclear-armed countries to go without limits on their arsenals because one would not join in arms control would be an act of sheer folly.

Lastly, at the very least, if the United States and Russia arrive in 2026 with no new arms control arrangement, the two countries must make a mutual commitment to continue adhering to the central limits of New START until such an arrangement is in place.

INF Missiles

The new arrangement should prohibit the development or limit the deployment of at least some types of missiles formerly banned by the INF Treaty. Although flawed, Russia’s proposal for a moratorium on the deployment of INF missiles, plus some verification measures, can serve as a starting point.

There are various routes available. For instance, one option could be to ban all nuclear ground-launched, intermediate-range missiles, as suggested by Rose Gottemoeller, chief U.S. negotiator for New START. Another option could be to prohibit the deployment of ground-launched, intermediate-range nuclear ballistic and cruise missiles in Europe and to the west of the Ural Mountains. Any of these or other options must ensure that verification is a key component and that Russia will address the currently deployed 9M729 missiles.

The motivation to pursue a variation of the INF Treaty in the next arms control arrangement rests on the fact that neither the United States nor Russia can afford another expensive, unnecessary arms race with another class of weapon and that these weapons heighten tensions. U.S. military officials have already expressed skepticism over efforts to bring ground-launched intermediate-range missiles to the Army.

There have also emerged issues with locations to base these missiles in Europe and Asia, a challenge that the Army has acknowledged. While Army Secretary Christine Wormuth argued in May that finalizing such basing decisions do not need to be made before the development of these missiles, experts have disputed this notion, as the location of the missile will influence its range requirement.

Furthermore, a U.S. introduction of these missiles into Europe (which would require NATO’s cooperation) would serve as a provocative threat to Russia, which has stated that it will respond in kind. In such a scenario, Europe would become flooded with missiles that are not a proven military necessity and would compromise European security.

Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons

The new arrangement should address non-strategic, or tactical, nuclear weapons. With an estimated 1,900 Russian tactical nuclear weapons in central storage and 100 U.S. tactical nuclear weapons deployed in Europe, these weapons are a point of interest for both countries.

Tactical nuclear weapons are understood as being designed for battlefield, or so-called limited, nuclear use and possessing shorter ranges and lower yields than strategic nuclear weapons. The thought process informing the development and the deployment of tactical nuclear weapons has generally been to have a smaller, more precise nuclear weapon that is more prompt than a strategic nuclear weapon. Yet, for comparison, the bomb dropped on Hiroshima was about 15 kilotons, which would be defined as tactical today, and many modern tactical nuclear weapons have far greater yields, into the hundreds.

“No one knows if using a tactical nuclear weapon would trigger full-scale nuclear war,” wrote Nina Tannenwald, an international relations professor at Brown University, in March.

Past arms control arrangements have yet to cover tactical nuclear weapons, though it has been a longtime goal to do so.

Numerous challenges lay ahead for incorporating tactical nuclear weapons into the next U.S.-Russia arms control arrangement (e.g., mutually agreeing to definitions of relevant terms, addressing the differing numbers of tactical nuclear weapons in each arsenal, establishing a suitable verification regime, etc.). Therefore, a simple option to begin tactical nuclear arms control would be to agree to exchange detailed declarations on tactical nuclear stockpiles, including warheads in storage.

Missile Defense

The new arrangement should institute numerical limits on missile defense interceptors and launchers. Given Russian (and Chinese) longtime concerns about U.S. missile defenses, there is almost no way in which a new arms control arrangement would be reached without effective limits on U.S. missile defense systems. Despite the technical challenges, the unimpressive testing record, and the steep costs for missile defense systems, the United States has continued to pursue these capabilities and dismiss any limits on them.

The ABM Treaty, as amended in 1974, limited the United States and Russia to 100 ground-based missile interceptors deployed at one site. Such a numerical limit could be revived without any adjustment to current or future force levels. In addition, the verification regime of the new arms control arrangement could require, similar to New START, a quota for on-site visits to missile defense facilities and advance notifications before interceptor flight tests.

Missile defense systems, particularly those meant to intercept strategic threats, do not perform reliably and effectively even under the most scripted of conditions and therefore do not provide reliable protection, making it no great loss to agree to reasonable limits on those systems. Besides, the United States agreeing to limit the quantity, location, and capability of missile interceptors for a limited ballistic attack from Iran or North Korea should not impede fielding the interceptors in a sufficient number.

Verification Regime

The new arrangement should maintain an on-site inspections and verification regime, similar to that of New START. The U.S. military has repeatedly gone on the record to confirm the great value of the New START verification regime, as, for instance, the information gathered through data exchanges cannot necessarily be attained through other avenues.

Although adjustments will likely have to be made to establish the process for inspections of new kinds of nuclear delivery vehicles, these should be rather straightforward changes.

Additional Nuclear-Armed Countries

U.S.-Russian arms control does not and should not exist in a silo. Therefore, alongside the steps on a new U.S.-Russian arms control arrangement outlined above, the following actions should also be taken:

- The five NPT-recognized nuclear-weapon states should implement various, effective risk reduction and conflict escalation management measures.

A measure that should be implemented as soon as possible is the official establishment and the consistent use of hotlines, or direct communication channels, between both political and military leaders of different countries. Washington and Moscow established a similar deconfliction line a few days after the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which proved a smart move as Russian missile strikes crept closer to NATO borders. In May and October, U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and Gen. Mark Milley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, talked to their Russian counterparts in an attempt to gain clarity on various claims and avoid miscommunication or escalation.

Additional potential measures include delaying tests of nuclear weapon delivery systems and nuclear exercises or related activities that could be perceived as particularly provocative. Austin delayed then canceled a scheduled test of the U.S. Minuteman III ICBM in early March to guard against any worst-case assumptions. Unfortunately, the United States and NATO moved ahead with the scheduled Steadfast Noon nuclear exercise in October, while Russia proceeded with nuclear exercises in the Kaliningrad enclave in May and in the Ivanovo province in June and has just begun its annual Grom exercises.

- The United States must, if it has not already, invite China to officially establish a U.S.-Chinese strategic stability dialogue that includes arms control among its main topics for discussion. Washington must propose to design the dialogue as a venue in which to set the foundation for potential arms control in the future. This means building familiarity with each country’s arms control officials, establishing a glossary of terminology for more detailed discussions, and so on. The first session of the dialogue should not include a demand that China immediately join in U.S.-Russian arms control processes, as that would likely prompt Chinese officials to walk right back out the door. Creating an official U.S.-Chinese strategic stability dialogue is the first step in a very long potential multilateral arms control endeavor.

In addition, the United States can consider augmenting the P5 forum—which involves senior officials from Washington, Moscow, London, Paris, and Beijing discussing their NPT obligations—to feature more formal arms control discussions and perhaps, in time, negotiations. One possibility in this venue is for China, France, and the United Kingdom to report on their total nuclear weapons holdings and freeze the size of their nuclear stockpiles so long as the United States and Russia pledge to pursue deeper verifiable reductions in their arsenals.

The top priority must be for the two countries to, at least, continue adhering to New START’s central limits until they successfully negotiate a new arrangement, although the better option would be to secure lower limits on strategic nuclear warheads and delivery systems in U.S. and Russian arsenals.

From there, Washington and Moscow can tackle missiles formerly banned by the INF Treaty, tactical nuclear weapons, U.S. missile defenses, and new and emerging technologies in the space and cyber domains, in this general order.

The achievement of a U.S.-Russian arms control framework to replace New START, plus the other actions for the five NPT-recognized nuclear powers, will require unwavering political will and determination in the currently charged strategic landscape, as well as pragmatism and compromise. However, the outlined steps must be taken to guard against the outbreak of nuclear war.

History demonstrates that the benefits of bilateral arms control agreements involving the possessors of the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals have consistently outweighed the costs. Now is the time to absorb lessons learned from previous arms control efforts and apply them to the negotiation of a new, effective, and more comprehensive arms control arrangement between the United States and Russia that addresses today’s current strategic and geopolitical environment, and before the existing nuclear arms control regime under New START ends. —SHANNON BUGOS, senior policy analyst