Volume 14, Issue 3, Feb. 28, 2022

Media Contacts: Daryl Kimball, executive director (202-463-8270 x107); Shannon Bugos, senior policy analyst (202-463-8270 x113)

In the midst of his catastrophic, premeditated military assault on Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin Feb. 27 ordered Russia’s nuclear forces to move to a higher state of alert of “a special regime of combat duty,” unnecessarily escalating an already dangerous situation created by his indefensible decision to invade another sovereign nation.

By choosing the path of destruction rather than diplomacy, Putin has launched a violent military assault that threatens millions of innocent civilians in independent, democratic Ukraine.

Putin has also sharpened tensions between Russia and member states of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), increased the risk of conflict elsewhere on the European continent, and derailed past and potential future progress on nuclear nonproliferation and disarmament, possibly for years to come.

Putin’s order to put Russia’s nuclear forces on higher alert is not a complete surprise given his previous implied threats against any nation that tried to stop him in Ukraine.

But clearly, inserting nuclear weapons into the Ukraine war equation at this point is extremely dangerous. It is essential that U.S. President Joe Biden along with NATO leaders act with extreme restraint and not respond in kind. This is a very dangerous moment in this crisis, and all leaders, particularly Putin, need to step back from the nuclear brink.

In justifying his actions, Putin has pointed to longtime grievances, such as NATO’s expansion eastward, and the specious claim that Kyiv has plans to build nuclear weapons or obtain them from the United States. Ukraine was neither headed for NATO membership any time soon nor seeking a nuclear weapons capability. Ukraine did not pose the kind of threat that Putin claimed to justify his invasion.

Tragically, Putin also bypassed diplomatic options that could have addressed many of Russia’s stated security concerns in Europe.

In December, Moscow transmitted to each the United States and NATO a proposal on security guarantees, which included several nonstarters, such as a prohibition on allowing Ukraine to join NATO.

Nevertheless, the Russian proposal, as well as the U.S. and NATO counterproposals, highlighted potential areas for negotiations to resolve mutual security concerns. Yet, with the invasion of Ukraine, Putin has made any further progress on arms control and risk reduction impossible, at least for the time being.

The 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), which is the only remaining treaty limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals, expires in four years, which is a short period of time for negotiating and securing the necessary domestic support for a replacement arrangement.

As we wrote last week, “Although Putin’s regime must suffer international isolation now, U.S. and Russian leaders must eventually seek to resume talks through their stalled strategic security dialogue to defuse broader NATO-Russia tensions and maintain common sense arms control measures to prevent an all-out arms race.”

Below are answers to frequently asked questions about Putin’s war in Ukraine, Russia’s nuclear weapons, and the risks of escalation.—DARYL G. KIMBALL, executive director, and SHANNON BUGOS, senior policy analyst

What did Putin say, what does it mean, and how should we respond?

Putin’s statement is probably designed to reinforce his earlier implied threats that were clearly designed to try to ward off any military interference in his attack on Ukraine, a non-nuclear weapon state.

“Western countries aren’t only taking unfriendly economic actions against our country, but leaders of major NATO countries are making aggressive statements about our country,” Putin said Feb. 27 in a meeting with defense officials. “So, I order to move Russia’s deterrence forces to a special regime of combat duty.”

A few days prior in his speech announcing his decision to invade Ukraine, Putin threatened any country that “tries to stand in our way or all the more so create threats for our country and our people” with consequences “such as you have never seen in your entire history.”

Putin’s threat is unprecedented in the post-Cold War era—and unacceptable. There has been no instance in which a U.S. or a Russian leader has raised the alert level of their nuclear forces in the middle of a crisis in order to try to coerce the other side's behavior.

The White House and NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg immediately denounced the move but did not indicate they would follow suit.

“This is really a pattern that we’ve seen from President Putin through the course of this conflict, which is manufacturing threats that don’t exist in order to justify further aggression,” White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki commented Feb. 27. “At no point has Russia been under threat from NATO [or] has Russia been under threat from Ukraine.”

“We have the ability to defend ourselves,” assured Psaki.

“This is dangerous rhetoric,” Stoltenberg said. “This is a behavior which is irresponsible.”

It is not clear at this point, however, what changes to Russian operational readiness Putin has put into motion. Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu reportedly told Putin Feb. 28 that all nuclear command posts have been boosted with additional personnel.

Yet, one senior U.S. defense cautioned that while there is “no reason to doubt the validity of this order[,]…how it’s manifested itself I don’t think is completely clear yet.”

Pavel Podvig, director of the Russian Nuclear Forces Project, tweeted Feb. 27 that he is unsure that “we are dealing with elevated readiness level,” adding that, in his view, “it’s different.” Rather, he proposed that Putin’s order “most likely…means that the nuclear command and control system received what is known as a preliminary command.” This type of command, Podvig described, brings the nuclear systems into a working condition, but it “is not something that suggests that Russia is preparing itself to strike first.”

“The basic idea here is clearly to scare ‘the West’ into backing down. But part [of] the danger here is that it's not clear to me Putin has a clear de-escalation pathway in mind (except for the capitulation of Ukraine),” tweeted James Acton, co-director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

What Putin’s threat to use nuclear weapons also underscores is that nuclear weapons cannot prevent nuclear-armed states from launching major wars and that they increase the risk of an armed conflict between nuclear-armed states and nuclear-armed alliances. Rather than increasing security, they increase the danger of war by way of fostering the possibility of miscalculation and advertent or inadvertent escalation.

In the case of Russia’s war against Ukraine, Putin is essentially using the threat of nuclear weapons as a cover for his massive invasion of a non-nuclear weapons state. Key U.S. officials share the view that nuclear weapons can provide cover for projecting conventional military force. Admiral Charles Richard, head of U.S. Strategic Command, said in remarks published in February 2021 that "We must acknowledge the foundation nature of our nation's strategic nuclear forces, as they create the 'maneuver space' for us to project conventional military power strategically."

Have U.S. or Russian leaders made any similar nuclear threats against one another since the end of the Cold War?

No. Putin’s public implied nuclear threats toward NATO and the United States and his decision to raise the alert status of Russia’s nuclear forces is unprecedented in the post-Cold War era.

However, during the Cold War, between 1948 and 1961 as well as the the period between the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis and into the mid-1970s, there were numerous nuclear threats and alerts designed to change the behavior of adversaries.

For example, President Richard Nixon and his national security adviser Henry Kissinger developed what he called the "madman theory," which posited that threatening massive, even excessive, levels of military violence, including nuclear attacks, would intimidate the North Vietnamese and their patrons in the Soviet Union into submission at the negotiating table.

On Oct. 9, 1969, Nixon and Kissinger instructed the Pentagon to place U.S. nuclear and other military forces around the globe on alert, and to do so secretly. For 18 days in October of that year, the Pentagon carried out one of the largest and most extensive secret military operations in U.S. history. Tactical and strategic bomber forces and submarines armed with Polaris missiles went on alert. This "Joint Chiefs Readiness Test" culminated in a flight of nuclear-armed B-52 bombers over northern Alaska.

The secret 1969 U.S. nuclear alert, though certainly noticed by Soviet leaders, failed to pressure them into helping Nixon win concessions from Hanoi. Nixon switched his Vietnam strategy from one of intimidation to one of steady troop withdrawals and Vietnamization—reinforced by rapprochement with China and détente with the Soviet Union. In the end, he exited Vietnam only after negotiating an unsatisfactory armistice agreement.

In the past, similar nuclear gambits have failed to work as intended. Such threats are unlikely to succeed when the side threatened possesses its own nuclear weapons capabilities, when a non-nuclear state or a guerrilla or terror group is presumably under the protection of a nuclear state, or when the nuclear threat is disproportionate and therefore not credible because it is aimed at a small country or non-state actor.

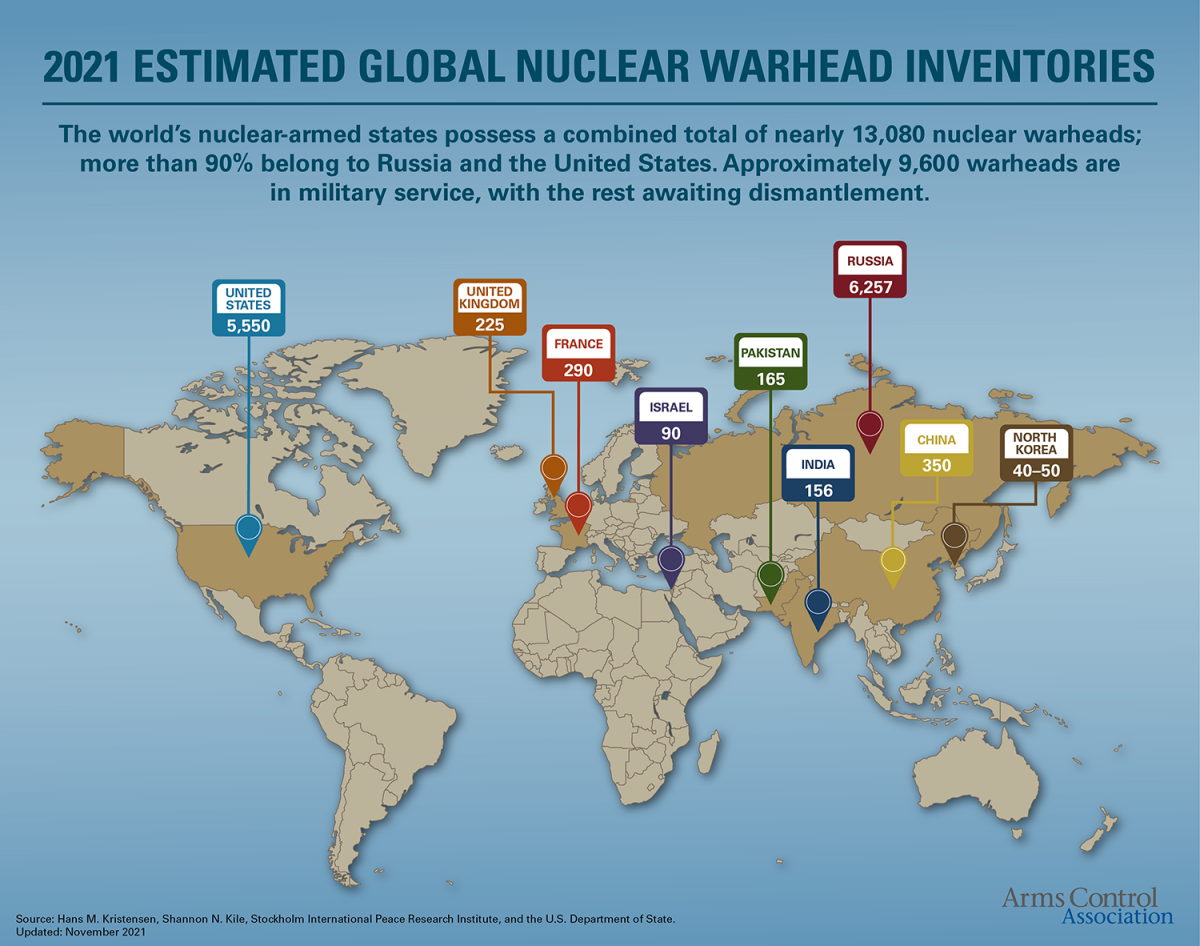

How many nuclear weapons do Russia, the United States, and NATO currently have?

The United States deploys 1,389 strategic warheads on 665 strategic delivery systems, and Russia deploys 1,458 strategic nuclear warheads on 527 strategic delivery systems as of September 2021 and according to the counting rules established by the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START). Both countries are currently modernizing their nuclear delivery systems.

Strategic warheads are counted using the provisions of New START, which Biden and Putin agreed to extend for five years in January 2021 but will expire in 2026. New START caps each country at 1,550 strategic warheads deployed on 700 delivery systems, including intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and heavy bombers assigned a nuclear mission.

The U.K. and France, also NATO members, are estimated to possess 225 nuclear warheads and 290 respectively.

The United States also has an estimated 160 B-61 nuclear gravity bombs that are forward-deployed across six NATO bases in five European countries: Italy, Germany, Turkey, Belgium, and the Netherlands. The total estimated U.S. B-61 stockpile amounts to 230.

In addition, Russia is believed to have an estimated 1,900 non-strategic, or tactical, nuclear weapons, all of which are thought to be in central storage, not deployed in the field.

Russia, like the United States, keeps its land-based ICBMs on a high state of readiness at all times, and it is believed that Russia’s SLBMs, like the U.S. forces, are similarly postured. The ICBM forces of both countries are maintained on a “launch-under-attack” posture, meaning they can be launched within minutes of an authorized “go” order by either leader and can arrive at their targets within 20 minutes or less. This posture leaves each side with very little time to make a decision about launching a retaliatory strike if they detect a launch of strategic nuclear weapons against their forces, which creates the risk that a false alarm could trigger nuclear war.

Sea-based strategic nuclear weapons, which are extremely hard to detect and destroy, can be fired nearly as quickly at their targets depending on their location. Other systems, such as strategic bomber-based weapons, take relatively more time to arm with nuclear weapons and reach their target launch points, but bombers can be recalled for a period of time after launch orders are given.

What are the policies governing U.S. and Russian nuclear use?

Both U.S. and Russian presidents have sole authority to authorize the use of nuclear weapons, meaning they do not require concurrence from their respective military and security advisers or by other elected representatives of the people.

Current U.S. and Russian military strategies reserve the option to use nuclear weapons first. In Russia’s case, its military policy allows for the president to order the use of nuclear weapons if the state is at risk or possibly if Russia is losing a major war. The theory is that a “limited” use of nuclear weapons could halt an adversary’s advances or even tip the balance back in favor of the losing side.

Some U.S. officials have argued for deployment of additional types of “more usable” low-yield nuclear weapons in the arsenal. However, even what are deemed low-yield nuclear weapons today still hold immense power. For instance, the low-yield W76-2, a new warhead deployed in late 2019 for U.S. submarine-launched ballistic missiles, is estimated to have an explosive yield of five kilotons, roughly one-third the yield of the bomb that the United States dropped on Hiroshima in 1945.

But once nuclear weapons are used in a conflict involving nuclear-armed adversaries—even if on a so-called “limited scale” involving a handful of “smaller” Hiroshima-sized bombs—there is no guarantee the conflict would not escalate and become a global nuclear conflagration.

Biden and Putin both seem to understand that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought,” a statement originally endorsed in 1985 by Presidents Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev and reiterated by the five countries with the largest nuclear arsenals in January 2022.

The former head of U.S. Strategic Command, Gen. John Hyten, described in 2018 how the command’s annual nuclear command and control and field training always ends. “It ends bad,” he said. “And the bad meaning it ends with global nuclear war.”

However, such a recognition among leaders does not mean a nuclear war will not break out. After all, Putin has demonstrated that he is an extreme risk-taker.

To reduce the risk of nuclear war and draw a strong distinction between Putin's irresponsible nuclear threats and U.S. behavior, Biden should adjust U.S. declaratory policy by clarifying that the sole purpose of nuclear weapons is to deter the first use of nuclear weapons by others. A sole purpose policy would rule out the use of nuclear weapons in a preemptive strike or in response to a non-nuclear attack on the United States or its allies, increase strategic stability, and reduce the risk of nuclear war.

In fact, during the 2020 presidential campaign, Biden wrote in Foreign Affairs: “As I said in 2017, I believe that the sole purpose of the U.S. nuclear arsenal should be deterring—and, if necessary, retaliating against—a nuclear attack. As president, I will work to put that belief into practice, in consultation with the U.S. military and U.S. allies.”

Ultimately, even the best intentions of one side cannot ensure that the interests of all to prevent the use of nuclear weapons will win out. Therefore, the only action that can actually prevent the use of nuclear weapons is the removal of these weapons from the battlefield and their verifiable elimination.

What would be the effects from an outbreak of nuclear war?

Beyond the many dangers to the millions of innocent people caught in Putin’s war of choice against Ukraine, there is also an increased risk that the war might lead to an even more severe, if unintentional, escalatory spiral involving NATO and Russian forces, both of which have nuclear weapons at their disposal.

The indiscriminate and horrific effects of nuclear weapons use are well-established, which is why the vast majority of the world’s nations consider policies that threaten nuclear use to be dangerous, immoral, and legally unjustifiable and consequently have developed the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW).

If Russian or NATO leaders chose to use nuclear weapons first in a conflict in Europe, the result could be a quick escalation from a local disaster into a European nuclear war and then a global catastrophe. Millions, perhaps tens of millions, would die in the first 45 minutes.

A detailed study published in 2002 assessed the direct consequences of a major conflict between the United and Russia.

The study concluded that if 350 of the strategic nuclear warheads in the Russian arsenal reached major industrial and military targets in the United States, an estimated 70 to 100 million people would die in the first hours from the explosions and fires.

The U.S. president could quickly retaliate with as many as 1,350 nuclear weapons on long range missiles and bombers and, in consultation with allies, another 160 nuclear gravity bombs on shorter-range fighter-bombers based in five NATO countries in Europe.

Many more people would be exposed to lethal doses of radiation. The entire economic infrastructure of the country would be destroyed—the internet, the electric grid, the food distribution system, the health system, the banking system, and the transportation network.

In the following weeks and months, the vast majority of those who did not die in the initial attack would succumb to starvation, exposure, radiation poisoning, and epidemic disease. A U.S. counterattack would cause the same level of destruction in Russia, and if NATO forces were involved in the war, Canada and Europe would also suffer a similar fate.

More recent scientific studies indicate that the dust and soot produced by a nuclear exchange of 100-200 detonations would create lasting and potentially catastrophic climactic effects that would devastate food production and lead to famine in many parts of the world.

What are the past and present arms control treaties that have limited U.S. and Soviet/Russian nuclear weapons? What is the status of those treaties?

During the Cold War and after, arms control agreements helped to win and maintain the peace.

However, there has been growing mistrust between Russia and the West in recent years, leading to and fueling the loss of pivotal conventional and nuclear arms control and/or risk reduction treaties through negligence, noncompliance, or outright withdrawal.

Some of these treaties, which have acted as guardrails preventing the outbreak of catastrophic conventional and nuclear wars, included:

- the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty, which was designed to prevent an unconstrained offense-defense arms race;

- the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, which reduced the danger of nuclear war in Europe by eliminating an entire class of missiles;

- the 1990 Conventional Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty, which was designed to prevent major conventional force and weaponry buildups on the European continent; and

- the 1992 Open Skies Treaty, which provided transparency about military capabilities and movements.

In the absence of these agreements, cooperation between the parties has eroded, concerns about military capabilities have grown, and the risk of miscalculation skyrocketed.

Of note is also the 1996 Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), which prohibits nuclear test explosions and established a global monitoring and verification network. The treaty has 185 signatories, including China, Russia, and the United States. During the course of the nuclear age, at least eight states conducted more than 2,000 nuclear weapon test blasts above ground, underground, and underwater. The CTBT has effectively halted nuclear test explosions. However, the treaty is not yet in force due to the failure of eight states to ratify, leaving the door to nuclear testing in the future ajar.

In addition, the United States and the Soviet Union—and later Russia—negotiated a series of treaties that capped and eventually reversed the nuclear arms race. These included:

- The 1972 Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I): Though important as the first such treaty, it only slowed the growth of the two countries’ long-range nuclear arsenals. It ignored nuclear-armed strategic bombers and did not cap warhead numbers, leaving both sides free to enlarge their forces by deploying multiple warheads onto their missiles and increasing their bomber-based forces.

- The 1979 SALT II: This treaty was never formally ratified because the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan later that year, but Reagan agreed to respect its limits.

- The 1991 Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I): This agreement, which expired in December 2009, was the first to require the United States and the Soviet Union to reduce their strategic deployed arsenals and destroy excess delivery systems through an intrusive verification involving on-site inspections, the regular exchange of information, and the use of national technical means (i.e., satellites). START I was delayed for several years due to the collapse of the Soviet Union and ensuing efforts to denuclearize Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Belarus by returning their nuclear weapons to Russia and making them non-nuclear weapons states under the nuclear 1968 Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) and parties to START I.

- The 1993 START II: This treaty called for further cuts in deployed strategic arsenals and banned the deployment of destabilizing multiple-warhead land-based missiles. However, it never entered into force due to the U.S. withdrawal in 2002 from the ABM Treaty.

- The 1997 START III Framework: This framework for a third START included a reduction in deployed strategic warheads to 2,000-2,500. Significantly, in addition to requiring the destruction of delivery vehicles, START III negotiations were to address “the destruction of strategic nuclear warheads…to promote the irreversibility of deep reductions including prevention of a rapid increase in the number of warheads.” Negotiations were supposed to begin after START II entered into force, which never happened.

- The 2002 Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT or Moscow Treaty): This treaty required the United States and Russia to reduce their strategic arsenals to 1,700-2,200 warheads each. Unfortunately, it did not include a treaty-specific verification and monitoring regime. SORT was replaced by New START Feb. 5, 2011 .

- The 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START): This legally binding, verifiable agreement limits each side to 1,550 strategic nuclear warheads deployed on 700 strategic ICBMs, SLBMs, and heavy bombers assigned a nuclear mission. The treaty has a strong verification regime. The United States and Russia agreed Feb. 3, 2021, to extend New START by five years, as allowed by the treaty text, until Feb. 5, 2026.

As a result of these agreements, the total stockpiles of the two countries have been slashed from their peaks in the mid-1980s at almost 70,000 nuclear weapons to about 10,000 total U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons today. Plus, we no longer live in a world in which nuclear-armed states are detonating nuclear test explosions to perfect new and more deadly types of nuclear weapons.

Nevertheless, the United States and Russia still currently possess far more nuclear weapons than necessary to destroy one another many times over and more than enough to deter a nuclear attack from the other.

Consequently, the United States and Russia should further reduce their nuclear stockpiles and work to get other nuclear-armed countries involved in the process and eventually in the agreements. In 2013, for instance, the Obama administration found that the United States could further cut its deployed nuclear arsenal to about 1,000 without sacrificing U.S. or allied security.

Unless Washington and Moscow resume talks to reach a new agreement to replace New START before its expiration, there will be no limits on the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals for the first time since 1972—and we risk an all-out nuclear arms race once again.

Admittedly, however, Putin’s destructive, indefensible war on Ukraine will make that task much tougher.

How should the United States and NATO respond to Putin’s threat and minimize the risk of an outbreak of nuclear war?

The danger of miscalculation and escalation, including to the nuclear level, among adversaries is real and high.

Though Russia has yet to locate military forces along the Ukrainian-Polish border, for instance, there is a possibility that Russian and NATO forces will engage militarily, prompting the situation to quickly spin further out of control.

There is also the potential for close military encounters elsewhere involving U.S./NATO and Russian aircraft, warships, and submarines.

In the days and weeks and months ahead, leaders in Moscow, Washington, and Europe, as well as military commanders in the field, must be careful to avoid new and destabilizing military deployments, dangerous encounters between Russian and NATO forces, and the introduction of new types of conventional or nuclear weapons that undermine shared security interests.

For example, the offer from Russia’s client state, Belarus, to host Russian tactical nuclear weapons, if pursued by Putin, would further undermine Russian and European security and increase the risk of nuclear war. Unfortunately, Belarus voted Feb. 27 in a referendum to abandon its status as a non-nuclear state.

How can the United States and Russia get nuclear arms reduction efforts back on track?

Due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Putin’s regime will and should face the consequences and suffer international isolation imposed through a strong and unified front.

For the time being, this isolation includes a suspension of the bilateral U.S.-Russian strategic stability dialogue, which Biden and Putin resumed in June 2021 and last convened in early January 2022.

Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman confirmed Feb. 26 that Washington will not proceed with the dialogue under the current circumstances, saying that she sees “no reason” to do so. The day prior, State Department Spokesperson Ned Price said that while “arms control is something that will continue to be in our national security interest,…we don’t have another iteration of the Strategic Stability Dialogue planned.”

Eventually, however, U.S. and Russian leaders must seek to resume talks through their bilateral strategic security dialogue in order to prevent even greater NATO-Russia tensions and maintain common-sense arms control and risk reduction measures.

The Russian proposal on security guarantees from December 2021 and the U.S. (as well as NATO) counterproposal from January 2022 contain areas of overlap, demonstrating that there is room for negotiations to resolve mutual security concerns. The areas with the most promise are related to crafting a new agreement similar to the now-defunct INF Treaty; negotiating a follow-on to New START; agreeing to scale back large military exercises; and establishing risk reduction and transparency measures, such as hotlines.

Washington must test whether Moscow is serious about such options and, if possible, restart the strategic stability dialogue—and they must try to do so before New START expires in early 2026, else the next showdown will be even riskier.

In the long run, U.S., Russian, and European leaders—and their people—cannot lose sight of the fact that war and the threat of nuclear war are the common enemies. Russia and the West have a shared interest in striking agreements that further slash bloated strategic nuclear forces, regulate shorter-range “battlefield” nuclear arsenals, and set limits on long-range missile defenses.

Should Ukraine have kept its nuclear weapons that it inherited from the Soviet Union? Will Ukraine seek to have nuclear weapons once again?

Putin’s invasion of Crimea in 2014 and the current invasion violate the 1994 Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances.

In 1994, the United States, Russia, and the United Kingdom signed this important agreement, which extended security assurances against the threat or use of force against Ukraine’s territory or political independence. In return, the newly independent Ukraine acceded to the nuclear 1968 Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) as a non-nuclear-weapon state and gave up the 1,900 nuclear warheads it inherited from the Soviet Union.

Ukraine did not have operational control of and could not have safely maintained those nuclear weapons. Any attempt by Kyiv to keep these nuclear weapons would only have resulted in greater danger for Ukraine, Europe, and the world.

Arguments that a nuclear-armed Ukraine would be safer today are fallacies, as are any claims that Kyiv seeks to build or obtain nuclear weapons. Nuclear weapons do not make anyone safer and instead pose an existential threat to all of us.

Putin’s takeover of Crimea in 2014 and this new, massive invasion in 2022 serve to undermine the NPT and reinforce the unfortunate impression that nuclear-armed states can bully non-nuclear states, thereby reducing the incentives for nuclear disarmament and making it more difficult to prevent nuclear proliferation.