Getting Back on Track to Zero Nuclear Weapons

July/August 2020

By Carol Giacomo

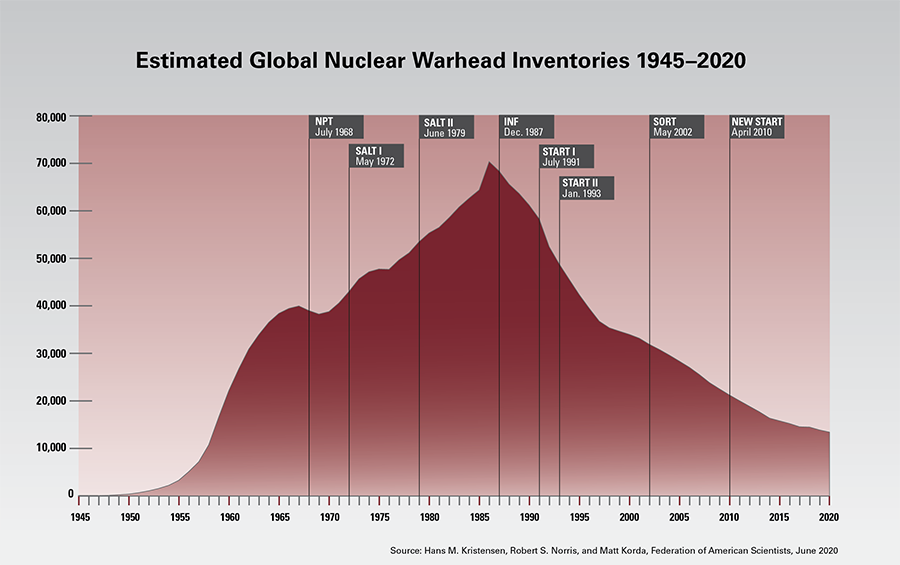

If there ever has been a fantastical national security goal, ridding the world of all nuclear weapons would be near the top of the list. At the height of the Cold War, the United States and Russia possessed a combined total of 68,000 of these most deadly armaments and although there have been significant reductions over the years, the two countries still account for an estimated 91 percent of the world’s nuclear weapons, which total more than 13,000 warheads.1

Even now, both are continuing to pour billions of dollars into new systems and supporting bureaucracies and industrial bases to produce, manage, and operate their arsenals. They still assign the weapons a primary role in their national defense doctrines. Both adhere to nuclear doctrines that call for the use of nuclear weapons against certain non-nuclear threats, and they maintain Cold War-era nuclear “launch under attack” policies that exacerbate the risk of catastrophic miscalculation. Meanwhile, a few other countries, notably North Korea, India, and Pakistan, are relentlessly advancing their own nuclear capabilities, proving that possessing the bomb and the means to deliver it against an enemy still has a darkly powerful appeal.

There are practical and political reasons to doubt that the nuclear genie can ever be completely returned to its bottle. Will any government follow South Africa’s example in the 1990s and really run the political risk of giving up their country’s entire nuclear weapons arsenal? Given the deeply rooted rationale that has justified the possession of nuclear weapons for three-quarters of a century and the growing tensions and rivalries between nations, how would that make the country safer? After all, the supposed magic of nuclear weapons is that they are capable of such catastrophic damage that no adversary would ever use one against another nuclear-armed state because it would invite certain retaliation and annihilation—mutual assured destruction. Americans were told, incorrectly, that they won the Cold War by outbuilding and outspending the Soviet Union, and many still believe that is a winning formula with Russia and China.

Even if all nuclear hardware and computer codes could be verifiably destroyed, how do you erase the knowledge locked in a scientist’s brain? Even if those questions can be convincingly answered, reducing and eliminating the threats posed by nuclear weapons no longer captivate the national psyche and animate national security agendas the way they once did. There is little sense of urgency in part because the task is so daunting, the challenges so complex, the goal seemingly distant.

Yet, the goal of global zero is as necessary and compelling as ever, maybe even more so. The Science and Security Board of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists this year moved its Doomsday Clock to 100 seconds before midnight, the symbolic threshold for nuclear calamity. In 1991, when the United States and Soviet Union were negotiating steep reductions in their arsenals, the clock stood at a far more comfortable 17 minutes to midnight.

Decades of popular pressure and hard-won diplomatic efforts have led to initiatives, treaties, and national policies that have curbed nuclear competition, nuclear proliferation, and many nuclear risks. Beginning in the late 1960s, the stockpile trajectory kept going down, and the United States and Russia were in regular dialogue on ways to mitigate the threats posed by nuclear weapons to both countries and to the world.

In 1970 the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) entered into force and established a binding commitment that all non-nuclear-weapon states forswear nuclear weapons and committed the nuclear-armed states-parties “to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament.”

The NPT was indefinitely extended in 1995 as part of a package of decisions that also committed the nuclear-armed states to a number of specific steps to help fulfill their disarmament commitments, one of which was to halt nuclear testing. In 1996, negotiations on the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) were concluded. Although the treaty has not yet entered into force, 184 countries have signed. There is now a global taboo against nuclear testing.

At the 2000 NPT Review Conference, states-parties underscored the end goal and agreed, by consensus, to further measures and called for an “unequivocal undertaking” to accomplish the total elimination of nuclear weapons.2

In recent years, however, momentum has slowed, and the destructive threat of the weapons themselves has been compounded by a precipitous erosion in the arms control regimes that for decades have helped keep nuclear arsenals in check. There has been a weakening of the democracies that have been central to managing the post-Cold War peace, and an explosion in campaign contributions from defense contractors keeps the pressure on members of Congress to ensure the nuclear doomsday machine remains intact.

The growing nuclear capabilities of the newest nuclear actors—India, Pakistan, and North Korea—continue to complicate the nuclear disarmament enterprise and pose potential nuclear flash points. Meanwhile, tensions between the United States and Russia are increasing, as are those between the United States and China, the rising nuclear-armed superpower. Nonstate actors continue to foment instability, and climate change, cyberwarfare, and space weapons pose new and worsening challenges.

Nothing in recent years, however, has done more to undermine arms control and nonproliferation efforts than U.S. President Donald Trump. He has not spoken at length about his nuclear weapons philosophy, but his comments during the 2016 campaign questioning why the United States possesses such weapons if it does not use them suggests a leader with no real understanding of their destructive power. Just days before Christmas in 2016, the president-elect tweeted that the United States “must greatly strengthen and expand its nuclear capability.” He later told MSNBC, “Let it be an arms race. We will outmatch them at every pass and outlast them all.”

Nothing in recent years, however, has done more to undermine arms control and nonproliferation efforts than U.S. President Donald Trump. He has not spoken at length about his nuclear weapons philosophy, but his comments during the 2016 campaign questioning why the United States possesses such weapons if it does not use them suggests a leader with no real understanding of their destructive power. Just days before Christmas in 2016, the president-elect tweeted that the United States “must greatly strengthen and expand its nuclear capability.” He later told MSNBC, “Let it be an arms race. We will outmatch them at every pass and outlast them all.”

Trump’s expansive interpretation of presidential power, willingness to act unilaterally, impulsive nature, and disregard for expertise have raised profound concerns about how he would handle a nuclear crisis. Along with a majority in Congress, he has embraced a nuclear modernization program launched by the Obama administration that will cost a budget-busting $1.5 trillion over the next 30 years, and he has issued a nuclear policy document that includes a new low-yield nuclear weapon that could make the use of such armaments more tempting.

Trump has surrounded himself with advisers, including at one time National Security Advisor John Bolton, who have a history of antipathy toward arms control, believing treaties and agreements are unacceptable legal restraints on what should be the United States’ total freedom to exercise power in whatever way it sees fit.

Trump has thrown roadblocks in the way of extending the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) that is set to expire in February after achieving verifiable reductions in Russian and U.S. deployed strategic nuclear warheads. He withdrew the United States from the landmark 2015 deal that put serious curbs on Iran’s nuclear program. He withdrew from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, which eliminated an entire class of missiles in Europe after perfunctory attempts to resolve a dispute over Russian noncompliance with the treaty. Over the objections of U.S. allies, he has announced plans to withdraw from the Open Skies Treaty, which allows the United States and its allies to fly over Russia and keep tabs on its military facilities. Furthermore, Trump officials assert that commitments made by the United States and others through the NPT review conferences no longer apply.

Now, his administration is considering whether to conduct the first U.S. nuclear test since 1992, for the purpose of sending political signals to Russia and China.3 In short, Trump has made it his mission to tear down rather than strengthen the diplomatic arms control architecture that has forced the United States and Russia to shrink their arsenals and helped prevent most other countries from becoming nuclear powers. It puts the president at odds with his predecessors from Dwight Eisenhower onward, who sought and negotiated or signed one or more nuclear arms control agreements while they were in office.

As illusory a goal as a world without nuclear arms might seem in today’s tumultuous political context, plenty of smart, sober-minded people believe it is still worthwhile. Few expect it to happen soon or perhaps ever. At a minimum, proponents are committed to zero as an aspirational target that can motivate international leaders and the public into taking decisions that propel the world on a path to fewer nuclear weapons instead of more and a diminished reliance on the ones that remain. The basic logic is this: If, as many senior officials and experts and former President Ronald Reagan and former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev have argued, “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought,” then why keep investing in expensive, civilization-destroying weapons when there are other needs to fund?

It is worth remembering that Reagan, a conservative Republican, was the first U.S. president to seriously contemplate eliminating nuclear weapons when he discussed a proposal with Gorbachev at their 1986 Reykjavik summit. Their vision ultimately faltered over Reagan’s refusal to forsake his dream of a costly and elaborate missile defense program, but the experience showed that it was possible for a defense hawk such as Reagan to transform into a nuclear peacemaker determined to end the balance of terror. The pair eventually negotiated the first Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty that, for the first time, mandated an actual reduction in the two nations’ long-range nuclear weapons arsenals.

Decades later, the man who had been Reagan’s secretary of state, George Shultz, is still committed to that ambitious vision. In a seminal commentary in The Wall Street Journal in 2007, Shultz and three other tough-minded national security titans—Henry Kissinger, the former secretary of state; Sam Nunn, the former Democratic senator from Georgia; and William Perry, the former defense secretary—gave new intellectual impetus to the cause by calling on the United States to lead a global campaign to devalue and eventually rid the world of nuclear weapons.4

“Nuclear weapons were essential to maintaining international security during the Cold War because they were a means of deterrence,” the four wrote. But they stressed, “It is far from certain that we can successfully replicate the old Soviet-American ‘mutually assured destruction’ with an increasing number of potential nuclear enemies worldwide without dramatically increasing the risk that nuclear weapons will be used.”

President Barack Obama picked up the theme in his 2009 Prague speech by giving assurances that the United States would seek a world without nuclear weapons. “The existence of thousands of nuclear weapons is the most dangerous legacy of the Cold War,” Obama said. “So today, I state clearly and with conviction America’s commitment to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons. I’m not naive. This goal will not be reached quickly—perhaps not in my lifetime. It will take patience and persistence. But now we, too, must ignore the voices who tell us that the world cannot change. We have to insist, ‘Yes, we can.’”5

Obama made a valiant stab at fulfilling his promise by negotiating New START with the Russians and the landmark nuclear deal with Iran and spearheading a global effort to better secure stockpiles of nuclear material. Yet, growing conflict over Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and interference in the 2016 U.S. election stymied further progress on nuclear disarmament.

In 2016, when Obama became the first U.S. president to visit Hiroshima, he seemed to express disappointment at the pace of nuclear disarmament, but still underscored the necessity of striving toward global zero. From the Hiroshima Peace Park, he said, “[W]e must have the courage to escape the logic of fear and pursue a world without them. We may not realize this goal in my lifetime, but persistent effort can roll back the possibility of catastrophe. We can chart a course that leads to the destruction of these stockpiles.”

Since then, Shultz and Perry, now in their 90s, have continued to try and shake a distracted world out of its torpor. Perry established a project dedicated to educating the public about nuclear threats and has published yet another book on the subject. “The likelihood of a nuclear catastrophe is greater today than during the Cold War, and the public is completely unaware of the danger,” he tells anyone who will listen.

The organization Global Zero, founded in 2008 by Bruce Blair, a nuclear expert and research professor at Princeton University, and others, has been a major driver internationally, as well as in the United States, behind eliminating nuclear weapons, with emphasis on laying out detailed blueprints for practical action toward the global zero goal. “I don’t believe in arms control for its own sake,” Blair told Arms Control Today. “It has to solve security problems and reduce the risk of deliberate or unintended use of nuclear weapons. In the long run, that means to eliminate them all.”

Other organizations and some governments have also sought to hold the world’s nuclear-armed states to their earlier nuclear disarmament commitments in the context of the NPT and to put us back on the path to a world without nuclear weapons.

Against considerable odds, a group of non-nuclear-weapon states backed by the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, has worked to harness such concerns. After years of campaigning, they secured the backing of 122 non-nuclear-weapon states to negotiate and open for signature the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.6 Although the United States and other nuclear-weapon states boycotted the process, advocates hope the treaty will help to delegitimize nuclear weapons and persuade the outlier nations, among them the United States, to eventually join.

Against considerable odds, a group of non-nuclear-weapon states backed by the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, has worked to harness such concerns. After years of campaigning, they secured the backing of 122 non-nuclear-weapon states to negotiate and open for signature the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.6 Although the United States and other nuclear-weapon states boycotted the process, advocates hope the treaty will help to delegitimize nuclear weapons and persuade the outlier nations, among them the United States, to eventually join.

Still, there is no underestimating the obstacles to escaping Trump’s dystopic world in which the arms control guard rails have been ripped off and the nuclear dangers threaten to overwhelm us.

If Trump is reelected, the problem may be insurmountable. One of his top arms control advisers, Marshall Billingslea, in a recent speech reaffirmed Trump’s past threat of a new arms race. “We know how to win these races, and we know how to spend the adversary into oblivion,” Billinsglea told the Hudson Institute, a Washington think tank. “If we have to do it, we will. But we would like to avoid it.”7

As Shultz told the Commonwealth Club in Los Angeles in May, when it comes to arms control, “it all starts at the top with the president. You can’t do it from down below.”8 His hope is that someone with influence, a friend of the president or perhaps a bipartisan Senate working group, can make a convincing case to Trump and his advisers to reverse course and take arms control seriously. It is a long shot, but presidents often look to seal their legacy with second-term accomplishments; and right now, Trump has no foreign policy wins in his column.

If former Vice President Joe Biden, the putative Democratic presidential candidate, wins in November, there is little doubt he will adopt a serious mainstream arms control agenda, given his long record of governmental service and published positions. Just how much of a priority Biden would assign to this agenda and whether he would adopt a transformational strategy with global zero as a broad goal or a more incremental approach is unclear. With the coronavirus pandemic, the collapse of the economy, and the turmoil over systemic racism facing the country, the next president’s plate will be full. Yet, progressive Democrats and others are urging Biden to think big on this and other matters in this moment of national crisis.

So, what could be a new president’s strategy for getting back on track to a world with fewer and eventually no nuclear weapons? There are many ideas for moving forward, but the following appear to have growing support.

Preserve and strengthen existing nuclear guardrails. The president should make clear in the first week in office that the United States is committed to work with Russia once again to lead international arms control efforts, which in the past have contributed significantly to stability. He must act quickly on the things a president can do on his own to stop the damage from Trump’s decisions: Tell Russia the United States is prepared to extend New START, which requires each side to have no more than 1,550 deployed strategic warheads and comply with a strict verification regime, for five more years. Tell Iran that if it goes back into compliance, the United States will immediately rejoin the 2015 nuclear deal under which Tehran observed strict curbs on its nuclear program in return for a lifting of sanctions. Recommit to the nuclear testing moratorium, the pursuit of entry into force of the CTBT, and a return to the Open Skies Treaty.

Declare the U.S. intent to adopt a no-first-use policy and to take land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) off launch-ready alert. The result would be to forswear the first use of nuclear weapons in a conflict, thus making clear the sole purpose of the U.S. arsenal is to deter a nuclear attack by others, not initiate one. The change would also give presidents more time to decide whether to launch a nuclear weapon, thus easing the pressure to strike preemptively and reducing the risk of launching based on a false warning. According to Global Zero, there is no more important or pragmatic step that could be achieved in the near term to reduce nuclear risks and advance the cause of disarmament than securing unequivocal statements of support by nuclear-armed states for a no-first-use policy. The president should consult with NATO on the impact of these changes on the alliance and urge Russia to follow the U.S. example.

Ensure no one person has control of the nuclear button. With a no-first-use posture and a move away from launch under attack, the president can and should work with Congress on legislation that would end the president’s sole authority to launch a nuclear weapon by requiring that such a decision can only be taken with the concurrence of the vice president and the secretaries of state and defense, and Congress.

Avoid a new European missile race. Test whether Russia is willing to agree on a mutual moratorium on the deployment of intermediate-range nuclear forces in Europe, thus halting the return of a destabilizing class of weapons that had been eliminated from the continent. The United States withdrew from the INF Treaty in 2019 after Russia violated the pact by deploying a banned new system, and now both sides are preparing to deploy these missile systems.

Rethink the current plan to replace and upgrade the U.S. arsenal. To create space for new nuclear weapons policies, pause defense budget expenditures allocated for nuclear modernization until an administration review of the program is completed and decisions are made. The pandemic, which has cost the government trillions of dollars, has caused Americans to think anew about what constitutes national security, like jobs and health care. In the context of today’s undeniable needs, it makes even less sense to squander resources on an excess of weapons that will never be used.

Build on New START. Begin talks with Russia on a follow-on agreement to New START that would aim to reduce each side’s arsenal even further and pave the way for countries with smaller nuclear arsenals, especially China, which has roughly 300 nuclear weapons and has resisted arms talks, to eventually join the discussion. Under the Global Zero plan, the new treaty would cover more types of systems (tactical and strategic) than the original version, leaving Russia and the United States with no more than 650 deployed warheads and 450 reserve weapons,9 compared to an estimated 1,550 deployed strategic and 150 nonstrategic nuclear warheads and 2,050 reserve warheads now.10 That would mean eliminating land-based ICBMs, which are considered vulnerable to attack, and scaling back the number of strategic nuclear-armed submarines and B-21 strategic bombers.

Sustain strategic stability talks with Russia and engage in separate talks with China. A trilateral Russian-Chinese-U.S. discussion could help all three explore not just views on nuclear weapons but other strategic topics such as missile defense, advanced conventional weapons, emerging Russian and Chinese anti-satellite weapons, confidence-building measures such as an early-warning center, and the impact of cyberwarfare on nuclear command and control, which is a growing U.S. concern.

Make nuclear disarmament a global enterprise. The United States has the power to convene a multilateral forum with nuclear-armed and non-nuclear states to discuss nuclear risks and other topics in preparation for a multilateral negotiation that results in the complete dismantlement of all nuclear weapons. This would be no easy task. China has resisted U.S. pressure to discuss restrictions on its 300-weapon arsenal, as have France and the United Kingdom, at least until U.S. and Russian levels are reduced far lower than current levels. India, Israel, North Korea, and Pakistan have also refused to subject their nuclear weapons to external restraints. How can they be engaged? One idea is to begin with a series of biennial summits at which states would make voluntary commitments to advance disarmament. Another would have the five recognized nuclear-weapon states (China, France, Russia, the UK, and the United States) jointly pursue some preliminary measures to foster nuclear stability among themselves, such as unilaterally pledging not to increase the size of their arsenals.

Restock the government’s cadre of arms control experts. Given all the experienced arms control experts and diplomats who left government during the Trump administration, there will be a need to woo back a new generation of diplomats and scientists to join the mission to mitigate nuclear dangers. Alexandra Bell, senior policy director at the Center for Arms Control and Nonproliferation, says younger people like herself are not burdened by “old grudges” between Russia and United States and can think more creatively about problem-solving.

Rebuild a coalition in support of nuclear risk reduction. It would help to build a constituency in Congress, among Americans, in foreign countries, and the expert and business communities in support of these steps and a world without nuclear weapons. In theory, there is sympathy in the United States for the global zero vision. Americans consider the spread of nuclear weapons among the top threats to the nation’s well-being, after coronavirus disease and terrorism, according to a March 2020 poll by the Pew Research Center. Yet, public support alone does not motivate elected officials in Congress to act. “I don’t think they know what nuclear weapons can do,” activist Jerry Brown, the former Democratic governor of California said recently. “If you go to Congress, there is very little interest in nuclear weapons.”

The outcome of the U.S. election and the actions taken in the next few years by the United States, Congress, and the American people, as well as other concerned leaders and citizens around the globe, will determine whether we continue to live under what President John Kennedy called “the nuclear sword of Damocles” for another 75 years or whether we find a way to remove ourselves from the dangers posed by nuclear weapons.

ENDNOTES

1. Hans M. Kristensen and Matt Korda, “Status of World Nuclear Forces,” Federation of American Scientists, April 2020, https://fas.org/issues/nuclear-weapons/status-world-nuclear-forces/.

2. 2000 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Final Document,” NPT/CONF.2000/28 (Parts I and II), 2000, p. 14.

3. John Hudson and Paul Sonne, “Trump Administration Discussed Conducting First U.S. Nuclear Test in Decades,” The Washington Post, May 22, 2020.

4. George P. Shultz, William J. Perry, Henry A. Kissinger, and Sam Nunn, "A World Free of Nuclear Weapons," The Wall Street Journal, January 4, 2007.

5. Office of the Press Secretary, The White House, “Remarks by President Barack Obama—Hradcany Square, Prague, Czech Republic,” April 5, 2009, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-barack-obama-prague-delivered.

6. For the current status, see International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, “Signature and Ratification Status,” n.d., https://www.icanw.org/signature_and_ratification_status (accessed June 24, 2020).

7. Hudson Institute, “Special Presidential Envoy Marshall Billingslea on the Future of Arms Control: Transcript,” May 21, 2020, https://www.hudson.org/research/16062-transcript-special-presidential-envoy-marshall-billingslea-on-the-future-of-nuclear-arms-control.

8. Commonwealth Club, “Reducing Nuclear Weapons: Stopping the War That No One Wants,” podcast, May 20, 2020, https://www.commonwealthclub.org/events/archive/podcast/reducing-nuclear-weapons-stopping-war-no-one-wants.

9. To learn more, see Global Zero, “We Have a Plan,” n.d., https://www.globalzero.org/reaching-zero/ (accessed June 24, 2020).

10. Kristensen and Korda, “Status of World Nuclear Forces.”

Carol Giacomo was a member of The New York Times editorial board from 2007 to 2020, writing about all major foreign and defense issues, including nuclear weapons, Iran, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Before that, she was diplomatic correspondent for Reuters in Washington, covering foreign policy for more than two decades and traveling to more than 100 countries with eight secretaries of state.