"No one can solve this problem alone, but together we can change things for the better."

Reflections on Injustice, Racism, and the Bomb

July/August 2020

By Vincent Intondi

The moment in August 2005 is seared into my memory. The train pulled up to the Hiroshima station from Kyoto. I stepped out with my mind full of images from 60 years ago, when the United States dropped the first atomic bomb on this pristine city of 340,000 people. (Hiroshima had been one of the few cities that escaped the fire-bombing campaign of Japan’s major cities led by U.S. Air Force General Curtis LeMay.) Initially, I was taken aback by what I saw: a modern city, filled with restaurants, hotels, shops, and lots of people, much like any other in the industrialized world.

Suddenly, everything changed. Clearly, I was not ready; and before I could prepare myself, I was standing in front of the iconic Atomic Bomb Dome—one of the few structures still standing in its original form near the hypocenter. Throughout my life, I had seen photos of the dome standing alone amid the total destruction wrought by the 15-kiloton atomic blast. But it was different being there in person. I could feel myself starting to change.

The next two days were filled with conversations with atomic bomb survivors (hibakusha), museum visits, and retracing the places about which John Hersey wrote in his historic work, Hiroshima. On the night of August 6, I saw thousands of Japanese citizens gathered at the Motoyasu River. People reflected on those who lost their lives, making paper floating lanterns and putting them in the water.

That night, with a few of my new Japanese friends (I was a student at the time at American University, which partnered with Ritsumeikan University), I put our lantern into the water. I still remember what I wrote on our lantern: “I will dedicate my life to making sure this never happens again.” As it floated away, I began to look around and think that 60 years ago, everyone here was dead. I thought of the human suffering that had taken place, and all of my anger, guilt, and sorrow boiled over as tears rolled down my face. At that moment, Koko Tanimoto Kondo, a hibakusha with whom I had grown close, immediately came over to console me.

When I returned to the United States, friends, family, and colleagues began hearing me talk about abolishing nuclear weapons. Many were perplexed. I had been known as an activist who fought for civil rights. I had become conscious when the phrase “Free Mumia” was dominant. I had spent my time protesting the murder of Amadou Diallo and the police assault on Abner Louima. “Who cares about nuclear weapons?” I heard. “Nukes will always be there…no one is crazy enough to use them,” and “That’s an issue for old, white dudes.”

But I could not forget what I learned, who I met, or how I felt in Hiroshima. Regardless if I was fighting for civil rights; against the inequities perpetuated by the World Trade Organization and International Monetary Fund; for justice for the indigenous people of Chiapas, Mexico; or to stop the U.S. war in Iraq, I kept coming back to one thought: What does any of this matter if we were all dead from nuclear war?

To me, it was simple. These were not separate issues. Jobs, racial equality, climate change, war, class, gender, and nuclear weapons were all connected and part of the same fight: universal human rights, with the most important human right being the freedom to live…live free from the fear of nuclear war.

Of course, this thinking is not new. Contrary to the narrative that nuclear disarmament has been and remains a “white” issue, since 1945, the anti-nuclear movement has included diverse voices who saw the value in connecting all of these issues. Moreover, the nuclear disarmament movement has been most successful when it left room for diverse voices and combined the nuclear issue with social justice.

The movement to abolish nuclear weapons began even before the first bomb was dropped. Among the earliest critics of nuclear weapons were the atomic scientists, members of the Roman Catholic Church, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, and many in the Black community. Specifically, regarding African Americans, for some, nuclear weapons were directly linked to racism.

Many African Americans agreed with Langston Hughes’ assertion that racism was at the heart of President Harry Truman’s decision to use nuclear weapons in Japan. Why did the United States not drop atomic bombs on Italy or Germany, Hughes asked. The Black community’s fear that race played a role in the decision to use nuclear weapons only increased when the U.S. leaders threatened to use nuclear weapons in Korea in the 1950s1 and Vietnam a decade later. For others, the nuclear issue was connected to colonialism. From the United States obtaining uranium from Belgian-controlled Congo to the French testing a nuclear weapon in the Sahara, activists saw a direct link between those who possessed nuclear weapons and those who colonized the nonwhite world. For many ordinary citizens, Black and white, however, fighting for nuclear disarmament simply meant escaping the fear of mutually assured nuclear destruction and moving toward a more peaceful world.

Today, many people love to quote Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., especially his “I Have a Dream” speech, while also ignoring the full title and focus of the march: “Jobs and Freedom.” Throughout his life, King made the connections of what he called the “triple evils” of capitalism, racism, and militarism.

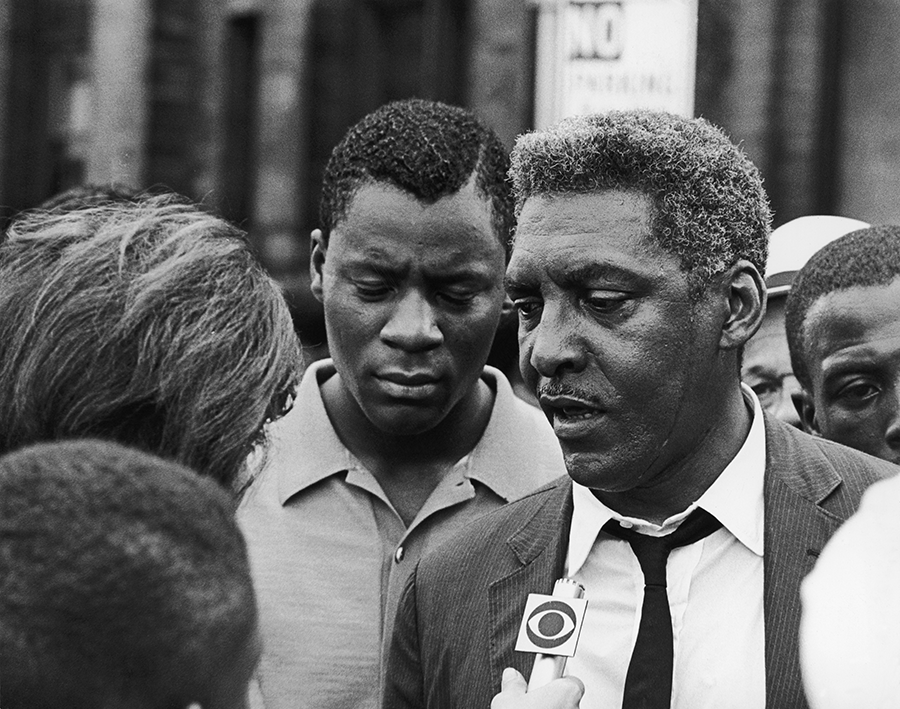

King was not alone among civil rights activists in making these connections. To put it in today’s context, to singer, actor, and activist Paul Robeson, “Black Lives Matter” meant not only speaking out about racism in the United States but also highlighting where the United States obtained its material to build nuclear weapons. To W.E.B. Du Bois, Black Lives Matter meant not only forming the NAACP or writing Souls of Black Folk, but also getting millions to sign the “Ban the Bomb” pledge to stop another Hiroshima in Korea. To civil rights leader Bayard Rustin, Black Lives Matter meant not only organizing the March on Washington but also traveling to Ghana to stop France from testing its first nuclear weapon in Africa. To Lorraine Hansberry, Black Lives Matter meant not only A Raisin in the Sun, but Les Blancs, her last play, about nuclear abolition. To Representative Ronald Dellums (D-Calif.), Black Lives Matter meant not only bringing jobs and education to Oakland, California, but also making sure President Ronald Reagan did not build the MX missile.

King was not alone among civil rights activists in making these connections. To put it in today’s context, to singer, actor, and activist Paul Robeson, “Black Lives Matter” meant not only speaking out about racism in the United States but also highlighting where the United States obtained its material to build nuclear weapons. To W.E.B. Du Bois, Black Lives Matter meant not only forming the NAACP or writing Souls of Black Folk, but also getting millions to sign the “Ban the Bomb” pledge to stop another Hiroshima in Korea. To civil rights leader Bayard Rustin, Black Lives Matter meant not only organizing the March on Washington but also traveling to Ghana to stop France from testing its first nuclear weapon in Africa. To Lorraine Hansberry, Black Lives Matter meant not only A Raisin in the Sun, but Les Blancs, her last play, about nuclear abolition. To Representative Ronald Dellums (D-Calif.), Black Lives Matter meant not only bringing jobs and education to Oakland, California, but also making sure President Ronald Reagan did not build the MX missile.

The prominent Black writer James Baldwin put it best on April 1, 1961, when he addressed a large group of peace activists at Judiciary Square in Washington. Baldwin was one of the headlining speakers for the rally, titled “Security Through World Disarmament.”

When asked why he chose to speak at such an event, Baldwin responded, “What am I doing here? Only those who would fail to see the relationship between the fight for civil rights and the struggle for world peace would be surprised to see me. Both fights are the same. It is just as difficult for the white American to think of peace as it is of no color.… Confrontation of both dilemmas demands inner courage.” Baldwin considered both problems in the same breath because “racial hatred and the atom bomb both threaten the destruction of man as created free by God.”

The power of diversity in the nuclear disarmament movement was perhaps most evident in the 1980s. With Reagan’s rhetoric of a “winnable nuclear war” and massive budget increases for nuclear weapons while cutting social programs that hurt the most vulnerable, the anti-nuclear movement grew exponentially. The nuclear freeze movement emerged.

New groups such as the Women’s Actions for Nuclear Disarmament, Feminists Insist on a Safe Tomorrow, Performers and Artists for Nuclear Disarmament, Dancers for Disarmament, and Athletes United for Peace formed. Established organizations such as Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy, the Union for Concerned Scientists, and Physicians for Social Responsibility all saw their membership skyrocket.2

For some, ending the nuclear arms race was and still is linked to their religious faith. Others saw a direct link between the amount of money being spent on nuclear weapons and eliminating badly needed social programs that benefited the poor. Many viewed and still view nuclear weapons as part of the overall military industrial complex, which included U.S. intervention in Central America and the Middle East, while for others, there was a genuine fear that the United States and Soviet Union would start a nuclear war.

This new sense of awareness, fear, and action culminated in the June 12, 1982, demonstration in New York’s Central Park, in which 1 million people of different races, genders, class, and religions marched and rallied for nuclear disarmament. As Randall Forsberg, one of the principal authors of the proposal for a nuclear weapons freeze, said in her speech to the throngs that day, “Until the arms race stops, until we have a world with peace and justice, we will not go home and be quiet. We will go home and organize.”

The rally, combined with other actions of the 1980s, contributed to the Reagan administration changing course on nuclear weapons, effectively showed the power of grassroots organizing, challenged the idea that the movement was not diverse, and paved the way for a new generation of activists committed to saving the world from nuclear annihilation.

The questions that we must ask ourselves today are how have we avoided nuclear war for the last 75 years and how can we sustain the popular support and awareness that is necessary to move policymakers to take the steps necessary to reduce and eliminate nuclear dangers. The answers: good luck and good organizing. There is nothing we can do about luck, except hope it is on our side. But by learning from the past, it is clear that there is much we can do as organizers, advocates, lobbyists, artists, writers, teachers, and just concerned citizens.

We need to make connections. Our power is in our diversity. The anti-nuclear movement needs to continue to reach out to marginalized communities and show the links between that amount of money spent on nuclear weapons and how those funds could be used for food, health care, jobs, housing, and education. Whether it is connecting with the religious, immigrant, LGBTQ, or Black communities, half the battle is showing up.

We need education. Far too many students go through their entire education, including college, without ever learning about the history of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki or the greater nuclear threat that has persisted since 1945. We must demand that curriculums across the country dedicate more time to the nuclear arms race and the movement to stop nuclear war. This means being involved on school boards and curriculum committees and creating the materials that we can distribute and incorporate into the various school systems.

We need artists. Part of the reason the nuclear issue resonated in the 1980s was because performers such as Jackson Browne, Rita Marley, James Taylor, Bruce Springsteen, Gil Scott-Heron, Harry Belafonte, and Linda Ronstadt, as well as various Hollywood and Broadway stars, performed, raised money, and lent their voices to the cause. We saw the power of this action when President Barack Obama was pushing the Iran nuclear deal.

We need filmmakers. One of the most successful strategies of the anti-nuclear movement in the 1980s was to create “The Day After.” Viewed by millions, this film, along with Helen Caldicott’s relentless pursuit of making sure the world knew the human effects of nuclear weapons, shook ordinary citizens to their core. We can and must replicate these actions to drive home the uncomfortable fact that nuclear weapons are a threat to everyone, everywhere.

We need to hold politicians accountable. Currently, we have a president who has threatened repeatedly to use nuclear weapons, has no problem spending billions on the nuclear arsenal, and may even want to resume nuclear testing. Moreover, we have local, state, and federal politicians who support the president’s decisions and are complicit in the march to nuclear competition and the perpetuation of the oppression imposed by the threat of nuclear weapons use. Whenever we have an opportunity to back a politician who fights for nuclear disarmament, we need to do so. We need to demand from our elected officials that they work toward the goal of nuclear abolition and indeed have some of our organizers within the movement run for office themselves. Of course, we need to vote.

We need to support the anti-nuclear movement and help it evolve. Much like new organizations that emerged in the 1980s, over the last decade we have seen groups such as Global Zero, Beyond the Bomb, and Don’t Bank on the Bomb and global disarmament networks such as the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons emerge. From the start, these groups have promoted intersectionality and made the connections among race, climate, feminism, and poverty in the fight to abolish nuclear weapons, not just in the United States but worldwide. In many cases, dynamic women have led this new movement. They are younger, with fresh ideas; savvy; and motivated. Whether one is in favor of working toward a no-first-use policy or a formal ban on nuclear weapons through negotiations at the United Nations, these organizers need our support, money, time, and respect.

With all this said, I cannot lie. I am saddened as I write this. Every five years on the anniversary of the first atomic bombings, the demand for my work seems to increase. Although I am thankful that I have the opportunity to write and speak about racism and nuclear weapons, this also means both are still with us.

Part of the problem is that we cannot wait until an anniversary of the atomic bombing or the release of another video of an unarmed person of color being murdered by police forces to talk about these issues.

Yet, I also remain hopeful. I find hope in the work of long-established groups such as the Arms Control Association, Ploughshares Fund, the Union of Concerned Scientists, and others. I find hope in younger anti-nuclear activists and the movement around the world to formally ban the bomb. I find hope in seeing so many in the streets demanding racial justice and refusing to remain silent in the face of hate, racism, and bigotry. But mostly, I remain hopeful that there will come a time, perhaps on another anniversary of Hiroshima, when I will be asked to write about the past when nuclear weapons and institutional racism once existed and were finally dismantled. Until that day, the fight continues, and we march on.

ENDNOTES

1. Vincent J. Intondi, African Americans Against the Bomb: Nuclear Weapons, Colonialism, and the Black Freedom Movement (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2015), pp. 29–31.

2. Paul Rubinson, Rethinking the American Antinuclear Movement (New York: Routledge, 2018), pp. 121–124.

Vincent Intondi is a professor of history and director of the Institute for Race, Justice, and Civic Engagement at Montgomery College in Takoma Park, Maryland. His research focuses on the intersection of race and nuclear weapons. He is the author of African Americans Against the Bomb: Nuclear Weapons, Colonialism, and the Black Freedom Movement (2015).