"No one can solve this problem alone, but together we can change things for the better."

U.S. to Withdraw From Open Skies Treaty

June 2020

By Kingston Reif and Shannon Bugos

The United States officially notified its intent to withdraw from the 1992 Open Skies Treaty, prompting bipartisan opposition in Congress and expressions of regret from U.S. allies.

President Donald Trump justified the withdrawal decision on the grounds that Russia was violating the agreement, but he said, “There’s a very good chance we’ll make a new agreement or do something to put that agreement back together.”

President Donald Trump justified the withdrawal decision on the grounds that Russia was violating the agreement, but he said, “There’s a very good chance we’ll make a new agreement or do something to put that agreement back together.”

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said in a May 21 statement that the withdrawal will take effect in six months. “We may, however, reconsider our withdrawal should Russia return to full compliance with the treaty,” Pompeo added.

Pompeo cited Russian noncompliance with the accord as “making continued U.S. participation untenable.” The United States asserts that Russia has violated the agreement by requiring that observation missions over Kaliningrad limit flight paths to 500 kilometers, establishing a 10-kilometer no-fly corridor along Russia’s border with the Georgian border-conflict regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, and denying a requested overflight by the United States and Canada in September 2019.

Pompeo also alleged that “Moscow appears to use Open Skies imagery in support of an aggressive new Russian doctrine of targeting critical infrastructure in the United States and Europe with precision-guided conventional munitions.”

Pressed to provide further information on this allegation on May 21, Christopher Ford, assistant secretary of state for international security and nonproliferation, said that he was “not at liberty to go into some of the details of why we think that this is a concern.” He then added, “[W]hile not a violation per se, it’s clearly something that is deeply corrosive to the cause of building confidence and trust.”

Asked about what Russia would need to do in order to return to compliance with the treaty, Ford said, “I would say that that’s a fact pattern we’ll have to deal with when we encounter it.”

The Defense Department said in a statement that “we will explore options to provide additional imagery products to Allies to mitigate any gaps that may result from this withdrawal.”

The Russian Foreign Ministry criticized the U.S. exit from the agreement in a May 22 statement, calling it “a deplorable development for European security.”

On the U.S. allegation that Russia is using the treaty to gather inappropriate intelligence, the statement said the “charge is being made by the party that insisted from the beginning on opening the entire territory of the participating states (above all, naturally, the [Soviet Union] and later Russia) to observation flights.”

The statement added that Russia’s future participation in the treaty “will be based on its national security interests and in close cooperation with its allies and partners.”

U.S. allies expressed varied responses to the U.S. exit from the treaty, but none of them signaled support for the move or indicated that they plan to follow the United States out of the agreement.

In a joint statement, 11 European countries (Belgium, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Luxemburg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden) expressed “regret” over the U.S. decision.

“We will continue to implement the Open Skies Treaty, which has a clear added value for our conventional arms control architecture and cooperative security,” they said. “We reaffirm that this treaty remains functioning and useful.”

NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg urged Russia to return to compliance with the treaty after a May 22 meeting of the North Atlantic Council. He said that the United States withdrew in a manner “consistent with treaty provisions.”

Poland said in a statement that efforts to return Russia to compliance “have proved unsuccessful.”

German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas noted that Germany, along with France, Poland, and the United Kingdom, had previously told Washington that Russian noncompliance concerns did not justify a U.S. withdrawal from the agreement.

Prior to the U.S. decision to withdraw, the Trump administration consulted U.S. allies and other states-parties to the treaty, including by distributing a written questionnaire earlier this year. Throughout the process, allies expressed their support for continued U.S. participation in the treaty. (See ACT, January/February 2020.)

Several Democratic and Republican members of Congress excoriated the withdrawal decision and accused the administration of breaking the law.

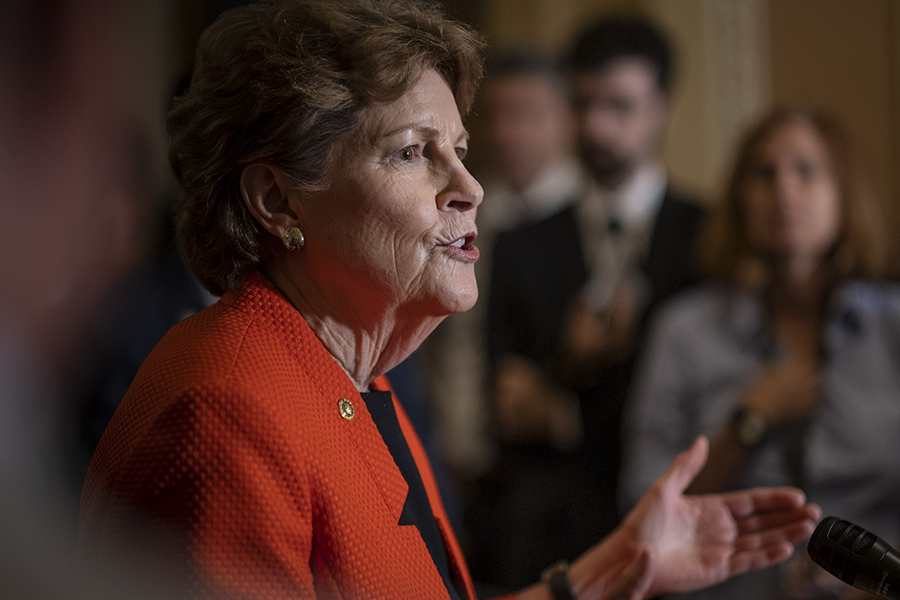

“The dangerous and misguided decision to abandon this international agreement cripples our ability to conduct aerial surveillance of Russia, while allowing Russian reconnaissance flights over U.S. bases in Europe to continue,” said Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-N.H.), who sits on the Armed Services and Foreign Relations committees.

“The dangerous and misguided decision to abandon this international agreement cripples our ability to conduct aerial surveillance of Russia, while allowing Russian reconnaissance flights over U.S. bases in Europe to continue,” said Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-N.H.), who sits on the Armed Services and Foreign Relations committees.

House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Eliot Engel (D-N.Y.) first sounded the alarm about the Trump administration’s plans to withdraw the United States from the treaty last October. (See ACT, November 2019.) Reacting to the withdrawal announcement, he said that “the president’s reckless plan…directly harms our country’s security and breaks the law in the process.”

The fiscal year 2020 National Defense Authorization Act required that the Trump administration notify Congress 120 days before announcing an intent to withdraw from the Open Skies Treaty, which it failed to do. (See ACT, January/February 2020.)

Sen. Bob Menendez (D-N.J.), ranking member of the Foreign Relations Committee, said that he does “not accept the legitimacy of the administration’s reckless decision.”

House Armed Services Committee Chairman Adam Smith (D-Wash.) and Rep. Jim Cooper (D-Tenn.), chairman of the committee’s strategic forces subcommittee, echoed the legal concerns and called the withdrawal “a slap in the face to our allies in Europe.”

Rep. Don Bacon (R-Neb.), who represents Offutt Air Force Base, where America’s OC-135B treaty aircraft are based, called the administration’s decision a “mistake.” He also urged that the administration adhere to the requirements in the defense authorization bill.

Meanwhile, Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.), a longtime treaty critic, voiced support for the withdrawal. He said that he was “particularly heartened” that the United States would now not have to fund the replacement efforts for the two treaty aircraft.

Congress appropriated $41.5 million last year to continue replacement efforts for these aircraft, but Defense Secretary Mark Esper in March told Congress that he halted the funding until a decision on the future of the treaty was made. (See ACT, April 2020.)

Signed in 1992 and entering into force in 2002, the treaty permits each state-party to conduct short-notice, unarmed observation flights over the others’ entire territories to collect data on military forces and activities. All imagery collected from overflights is then made available to any of the 34 states-parties.

Since 2002, there have been nearly 200 U.S. overflights of Russia and about 70 overflights conducted by Russia over the United States. Between 2002 and 2019, more than 1,500 flights took place.