"I greatly appreciate your very swift response, and your organization's work in general. It's a terrific source of authoritative information."

Old Chemical Weapons: Moving the OPCW to an Active Role

June 2020

By Dominique Anelli

The global inventory of chemical weapons was once enormous, especially in the United States and Soviet Union, but today 98 percent of them have been destroyed. Most of this destruction took place after the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) took effect in 1997, and the treaty’s implementation body, the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), has verified the elimination process.

As its verification-of-destruction role recedes, the OPCW has undertaken additional responsibilities that, for some, were not originally defined during the CWC’s negotiation. For example, the OPCW has increased its counterproliferation efforts by annually inspecting about 240 industrial sites to ensure their peaceful nature. In 2018, a special session of the OPCW Conference of States Parties empowered the OPCW to investigate and identify the perpetrators, organizers, sponsors, or those otherwise involved whenever chemical weapons are used. The agency’s Technical Secretariat is currently working to establish the basis for this investigation and identification team.

As its verification-of-destruction role recedes, the OPCW has undertaken additional responsibilities that, for some, were not originally defined during the CWC’s negotiation. For example, the OPCW has increased its counterproliferation efforts by annually inspecting about 240 industrial sites to ensure their peaceful nature. In 2018, a special session of the OPCW Conference of States Parties empowered the OPCW to investigate and identify the perpetrators, organizers, sponsors, or those otherwise involved whenever chemical weapons are used. The agency’s Technical Secretariat is currently working to establish the basis for this investigation and identification team.

Another important task remains for the OPCW: to assist in the recovery and destruction of old chemical weapons worldwide that were buried on land or dumped in water. Such munitions represent a dual threat for the international community. Their chemical agents could still be used as weapons, and they could damage the environment by contaminating soil and water. Many CWC states-parties do not have the means to address such a massive task on their own. If no action is taken, however, centuries could pass before old chemical weapons would fully deteriorate.

By taking this action, the OPCW will move ever closer to achieving its ultimate objective: the eradication of an entire category of weapons of mass destruction.

The Scope of the Problem

For buried old chemical weapons, it is difficult to make an estimation of the remaining quantities. About 20 states-parties have declared stocks of old chemical weapons to the OPCW, and many have begun to destroy them. Old chemical weapons continue to be found regularly, but because of the destruction burden and the absence of international incentives, some countries have not declared their discoveries. It is known that buried old chemical weapons exist in China, Europe1, Japan, and the United States and in some extraterritorial chemical weapon burial sites where they could be considered as abandoned chemical weapons.

As for munitions dumped at sea, one estimate assesses that 1.6 million tons of chemical munitions have been discarded at sea.2 In European waters, for example, nations have dumped about 450,000 tons of a mix3 of dumped chemical and conventional weapons, the most affected area being the Baltic Sea. In France, 250 tons of old chemical weapons are stored at the Suippes military facility in a northeastern region of the nation, and 10 to 20 metric tons of buried old chemical weapons are recovered annually, although these numbers can jump significantly when old munitions are discovered in the course of construction4 or roadwork. The provisional pace of destruction at newly opened destruction facilities in France is about 20 tons per year, with capacity expected to double during the first 20 years, allowing for the destruction of the Suippes munitions depot. This means some known, existing buried stockpiles will remain untouched for the next two decades or more, representing a permanent threat and an environmental risk.

Fortunately, with respect to dumped munitions in France, numerous destruction facilities were constructed up until 1950 to destroy the chemical arsenal inherited from World War I. Yet despite those destruction sites, delays in destruction operations forced the French authorities to dump chemical weapons at sea. In 1921, 11,456 tons of chemical weapons were dumped 40 miles from Dunkirk. Around 1950, 250,000 grenades filled with mustard agent and about 800,000 conventional munitions, all from World War I, were dumped off the coast of Toulon.5 After World War II, due to its political stance at this time, France did not actively participate in the massive dumping in European waters. Notwithstanding, chemical munitions from the Second World War were dumped by the Allies in North Gascogne, the Gulf of Gascogne, and off the coast of Saint Raphael, France.

Belgium has a smaller inventory of old chemical weapons and for the last 30 years has been able to destroy old munitions as they are recovered at its destruction facility at Poelkapelle. The historical recovery rate suggests, however, that destruction activity will continue for the next few centuries. Belgium has assisted other nations as well, destroying one old chemical weapon from the Netherlands in 2013, using an OPCW procedure that Austria employed in 2007.

With respect to dumped munitions, a technical assessment of Belgium’s Paardenmarkt sandbank, in front of Knokke beach, was launched recently. After World War I, in the absence of any destruction facilities at that time, more than 15,000 tons of chemical weapons were dumped there in shallow waters. Should a decision be taken to recover these munitions, Belgium will require international support6 to take on this challenge. In any case, substantial work will be needed to secure these dumped chemical weapons because they are near populated areas and in shallow waters.

Meanwhile, fishing vessels from Baltic nations regularly recover sea-dumped chemical munitions in their nets. Those old chemical weapons do not belong to the nations that recover them—the Baltic countries never produced chemical weapons—but now they must store them or destroy them with little support from the international community. As a result, these discoveries are not reported to the OPCW.

Meanwhile, fishing vessels from Baltic nations regularly recover sea-dumped chemical munitions in their nets. Those old chemical weapons do not belong to the nations that recover them—the Baltic countries never produced chemical weapons—but now they must store them or destroy them with little support from the international community. As a result, these discoveries are not reported to the OPCW.

Germany and the United Kingdom have officially declared their old chemical weapons stockpiles as destroyed, but they retain latent destruction capabilities from their earlier programs. Germany has assisted with the destruction of old chemical weapons recovered in Austria, after the OPCW determined that those munitions posed an imminent environmental danger.

Europe is not the only problematic region. The United States also has notable quantities of old chemical weapons. “Approximately 250 sites in 40 states, the District of Columbia, and three territories are known or suspected to have buried chemical warfare materiel,” according to the U.S. Department of Defense.7

To tackle this challenge, the United States created the Recovered Chemical Materiel Directorate (RCMD) in 2012 under the umbrella of the U.S. Army Chemical Material Activity (CMA). The RCMD maintains a large resource of expertise and equipment to continue8 the destruction of recovered old chemical weapons in full transparency with the OPCW. As for munitions dumped at sea, the Defense Department “believes it is best to leave the sea-disposed munitions in place unless there is an explosives emergency or serious threat to human health or the environment.”9

Security and Environmental Risks

As old chemical weapons remain around the world, generally in known locations, some of them buried or dumped in shallow water could be easily accessible to malicious actors. The munitions would not function as originally designed, but they could nevertheless be used as a type of chemical dirty bomb that would cause serious psychological effects and mass disruption.

Such effects were evident, for example, following the 2018 chemical agent in Salisbury, UK. Everybody remembers the tremendous efforts deployed to isolate and decontaminate the potentially contaminated areas. If the Salisbury incident involved just a few grams of a chemical agent, imagine the devastating aftermath of a dirty chemical bomb containing 500 grams of mustard gas in an urban area. The cost of life might not be so high but the psychological and economic impacts would be serious.

The risks to the environment may be more substantial. A program funded by the European Union called CHEMSEA has investigated the environmental impacts of chemical munitions dumped in the Baltic Sea, detecting at least one chemical agent in one-third of the sediment and sea life samples collected.10 Those positive samples included chemical agents in cod and mussels that could make their way into kitchens around the world. Another study of sea-dumped chemical munitions developed a model that predicted that sunken chemical munitions containers will release their agents over the course of decades. Underwater shells containing mustard, for example, would begin to leak about 70 years after they were dumped and then continue for more than 250 years.11

The risks to the environment may be more substantial. A program funded by the European Union called CHEMSEA has investigated the environmental impacts of chemical munitions dumped in the Baltic Sea, detecting at least one chemical agent in one-third of the sediment and sea life samples collected.10 Those positive samples included chemical agents in cod and mussels that could make their way into kitchens around the world. Another study of sea-dumped chemical munitions developed a model that predicted that sunken chemical munitions containers will release their agents over the course of decades. Underwater shells containing mustard, for example, would begin to leak about 70 years after they were dumped and then continue for more than 250 years.11

The CHEMSEA program provides a snapshot of the current situation in the Baltic Sea, just one dumping ground and one where sea currents are not strong and waters are shallow. Despite its Baltics-focused research, it suggests there are much wider concerns when all dumping grounds are considered.

Tailored Solutions

This ticking time bomb cannot be ignored, but OPCW states-parties have been slow to act, discouraged by high costs and the lack of substantial international support. For many, all they can manage is compliance with existing CWC requirements, not additional activities. The OPCW should adopt a larger role in supporting efforts to identify, recover, declare, and destroy old chemical weapons.

Solutions exist, providing there is political willingness on the part of states-parties. With their support, the OPCW could serve as the catalyst for international awareness on this issue. To do this, the CWC would need to be updated and modified. Then, the OPCW would need to work in collaboration with other multilateral organizations involved with this issue. In addition, financial support would be required, and the private sector could be included. For example, Kanda Harbour (Japan) and Nord Stream (the Baltic Sea) have already proven their ability to find technical solutions to address the destruction of underwater munitions.

The OPCW is uniquely qualified to launch and lead this ambitious objective. As a first step, the states-parties need to establish the legal framework, from their decisions or CWC modifications, and increase their financial support12 to the OPCW. The Technical Secretariat already possesses the necessary in-house human resources expertise and technical tools to enable implementation of the different tasks.

The organization has already shown its ability to take on and fund new tasks. In 2013, the international community was able to mobilize hundreds of millions of dollars for the destruction of chemical weapons in Syria. A OPCW-UN team was mandated to oversee the elimination of Syria’s declared chemical weapons in the safest possible way and within a strict international time frame. Importantly, part of the plan adopted by states-parties and the UN Security Council called for disposing of the Syrian chemical agents outside the nation’s borders, marking a groundbreaking development not contemplated in the treaty.

Investing in destroying old chemical weapons would be saving for the future. In Europe, some states-parties build and maintain old chemical weapons destruction sites at huge costs to destroy their own stockpiles. Others are not encouraged to declare their suspect discovered items because by declaring new discoveries, states-parties are obliged to host OPCW inspections13 and to destroy any chemical munitions in dedicated facilities. A better way would be for the EU Working Party on Disarmament and Arms Control (CODUN) to coordinate the efforts by states-parties to encourage EU cooperation for the destruction of old chemical weapons. By doing so, the facility built by one member could serve other nations. In the future, CODUN could coordinate, finance, and delegate the service to the OPCW of one or more mobile destruction facilities. When necessary, such a mobile unit could be deployed worldwide to perform destruction activities under the leadership of the EU and the OPCW.

With this in mind, the time seems ripe for the OPCW, with the support of the International Dialogue on Underwater Munitions, the Helsinki Commission (HELCOM), and the Oslo-Paris Convention to now take on the challenges of buried and sea-dumped old chemical weapons. With more than 20 years of experience verifying the destruction of chemical weapons, the OPCW could support and coordinate work on the destruction of buried old chemical weapons and launch investigations and recoveries of underwater dumped chemical munitions.

As a first step, states-parties would need to rethink the CWC. In pondering this question, it would be wise to remember that when the CWC was negotiated during the 1980s, stockpiles were huge.14 At the time, two blocs were opposing each other’s vision of the world order. The threats are different today; they are diffused, multidimensional, and changeable. The OPCW needs to adapt the treaty’s content to face such new challenges. For example, at a time when chemical weapons destruction deadlines have largely passed, is it necessary to keep such obligations? For old chemical weapons, the treaty established two definitions: munitions produced before 1925 and those produced between 1925 and 1946 that have deteriorated to such extent that they can no longer be used as chemical weapons. In 2020, are such definitions still relevant? It would be preferable to adopt a single definition: chemical weapons produced before 1946. This would simplify the old chemical weapons declaration process and states-parties’ destruction obligations.

Secondly, the OPCW needs to identify and engage with multilateral organizations in charge of buried or sea-dumped munitions. The United Nations has an important role to play and already has taken some steps. In December 2013, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution titled “Cooperative measures to assess and increase awareness of environmental effects related to waste originating from chemical munitions dumped at sea.”15 Without creating any formal legal obligation to implement, the resolution called for studies and recommendations “for the purpose of promoting international cooperation in the economic…and health fields.”16 In addition, UN Secretary-General António Guterres established a special envoy for the ocean in 2017, appointing Peter Thomson of Fiji to the post.

Other needed institutions include the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic, which was opened for signature at the ministerial meeting of the Oslo and Paris Commissions in September 1992. It was adopted with a final declaration and an action plan. The convention entered into force on March 25, 1998.

At the regional level, there is the Barcelona Convention, which was adopted in 1976 to prevent and abate pollution in the Mediterranean Sea. Similarly, there is HELCOM,17 an intergovernmental organization that governs the Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area.

Despite their existence, none of organizations have the legal authority nor the necessary tools to compel OPCW states-parties to retrieve old chemical weapons. Until such time as that changes, nothing will be done to recover the thousands of tons of chemical weapons buried or dumped underwater.

In parallel with political, financial, and organizational endeavors, it will be necessary to address the technical challenges of destroying old chemical weapons, buried or submerged. The last 25 years of chemical weapons destruction demonstrate that unforeseen costs and technical difficulties are likely to emerge. For buried old chemical weapons, the real challenge is the transport of the munitions from the recovery site to the destruction facility. At times, some states-parties, such as the United States, have opted to deploy a mobile destruction unit close to the recovery site. In Europe, however, there is no such capacity; states-parties are obliged to carry out in situ destruction, sometimes beyond the scope of CWC obligations.18 Some mobile destruction facilities financed by the EU and served by the OPCW would fill this capacity gap.

For underwater old chemical weapons, some innovative solutions have been used in Japan and the Baltic Sea. At Kanda Harbor in 2004, Japan found some dumped chemical munitions, which they declared to the OPCW. After scanning the bay and assessing the problem, authorities decided to place two mobile destruction facilities on a maritime platform. After underwater packaging, the munitions were treated in one of the two DAVINCH system detonation chambers.19

In 2011 the Nord Stream I project, the first part of a twin underwater gas pipeline through the Baltic Sea from Russia to Germany, needed to clear a seabed path for the pipeline and encountered dumped old chemical weapons. The submerged items, at depths of approximately 70 to 120 meters, were screened and then destroyed on-site when necessary.20

The dumped chemical munitions stockpile of the Paardenmarkt sandbank in Belgium could be used as a case study. It would offer the opportunity to put in place some funding and to develop all the political, organizational, and technical tools necessary to address internationally the problems of dumped chemical munitions. With states-parties’ support, the OPCW could serve as the forum where such projects are discussed, approved, coordinated, and managed. At the end of 2013, when choosing four industrial sites21 to destroy the Syrian chemical weapons, the OPCW clearly demonstrated its abilities to manage international destruction processes.

The fact that buried or sea-dumped old chemical weapons do not receive much notice in a world of problems competing for attention does not mean the security and environmental threats are any less. Without the leadership and support of an international organization, most individual nations do not have the financial means, the technical resources, or the incentive to take on such a challenge. Only through international cooperation can this worldwide peril be addressed.

ENDNOTES

1. Austria, Belgium, Italy, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, Russia, Switzerland and the UK have declared recoveries and destruction of old chemical weapons.

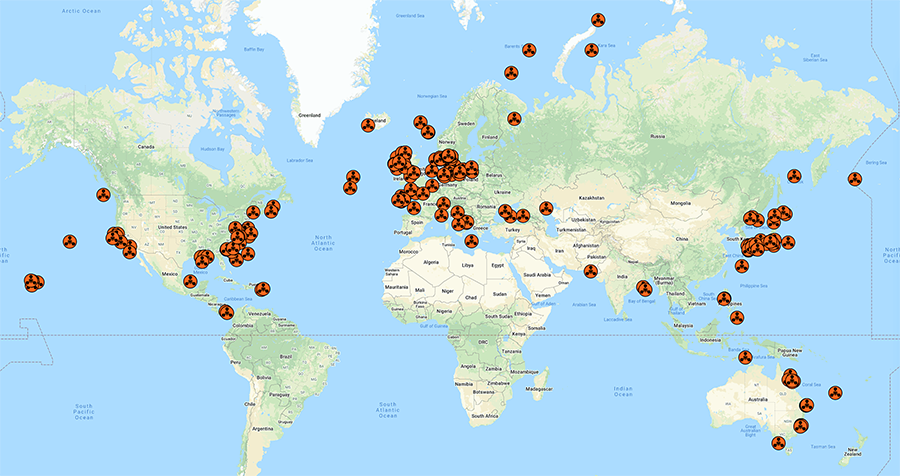

2. Ian Wilkinson, “Chemical Weapon Munitions Dumped at Sea: An Interactive Map,” September 7, 2017, https://www.nonproliferation.org/chemical-weapon-munitions-dumped-at-sea/.

3. Chemical weapons represent approximately 20 to 30 percent of this amount.

4. During construction of the railway line from Paris to Strasbourg over a four-year period, the number of old chemical weapons recovered annually increased.

5. Daniel Hubé, Sur les traces d’un secret enfoui (Paris: Michalon, 2016), pp. 222–223.

6. Pending political decisions to be taken by states-parties, and with EU financial support, the OPCW could serve as the catalyst for such destruction efforts with the financial support of the European Union.

7. National Research Council, Remediation of Buried Chemical Warfare Materiel (Washington: National Academies Press, 2012).

8. In the United States, recovered old chemical weapons are considered and treated as chemical weapons, and OPCW inspectors are invited to oversee the destruction.

9. Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, U.S. Department of Defense, “Research Related to Effect of Ocean Disposal of Munitions in U.S. Coastal Waters,” December 2016.

10. A total of 180 sediment samples were taken during the campaign.

11. Wojciech Jurczak and Jacek Fabisiak, “Corrosion of Ammunition Dumped in the Baltic Sea,” Journal of KONBiN, Vol. 41, No. 1 (2017): 227–246.

12. Should states-parties allow, the financial support provided for the destruction of chemical weapons from Syria could continue to be used for such purposes.

13. For buried old chemical weapons, the OPCW needs to move from a declaration mode to an assistance mode.

14. More than 70,000 tons of chemical weapons were declared to the OPCW after entry into force of the treaty.

15. UN General Assembly, A/RES/68/208, January 21, 2014.

16. UN Charter, arts. 13(1)(b), 13(2).https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/68/208https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/68/208

17. In 2014, the Helsinki Commission with the support of the EU released an important study on the assessment of chemical munitions dumped in the Baltic Sea. Chemical Munitions Search and Assessment Project, “CHEMSEA Findings: Results From the CHEMSEA Project,” 2014.

18. When made aware of such difficulties, the OPCW Technical Secretariat tries to help states-parties to destroy the old chemical weapons, an overriding objective of the OPCW. In the absence of incentives by the OPCW, some states-parties do not declare their recoveries.

19. The DAVINCH system is a vacuum detonation chamber in which the munitions are destroyed by explosive donor charges. The chamber is followed by a waste treatment system to avoid any atmospheric pollution. The metallic parts are recovered and packed for further treatment, in case of arsenic content.

20. Nord Stream, “Nord Stream Preparing for Munitions Clearance,” October 2, 2009, https://www.nord-stream.com/press-info/press-releases/nord-stream-preparing-for-munitions-clearance-366/.

21. Four sites were selected: Finland, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Dominique Anelli is a consultant in chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear defense matters. He served at the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons as head of the chemical demilitarization branch from 2007 to 2016. He has been recognized for his role in the verification of destruction of the Syrian chemical weapons.