The Past, Present and Future of the Chemical Weapons Convention

Daryl G. Kimball, Executive Director, Arms Control Association

Conference on Chemical Weapons, Armed Conflict, and Humanitarian Law

Queens University, Kingston, Ontario

October 29, 2018

Good afternoon. Thanks to the Canadian Red Cross for inviting me here to Queens University to participate in this important and timely conference on one of the world’s most dangerous types of weapons.

Chemical weapons use has been outlawed worldwide for over 90 years and outlawed comprehensively through the 1997 Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), which bans all development, production, and deployment of deadly chemical arms and requires the verifiable destruction of remaining stockpiles.

Over the past twenty-plus years of the CWC’s existence, it has become a very sophisticated, resilient and effective disarmament regime. The OPCW has been tremendously successful in overseeing the demilitarization of vast chemical weapons stockpiles.

But the work of eliminating prohibited chemical weapons stockpiles is not quite over.

But the work of eliminating prohibited chemical weapons stockpiles is not quite over.

Not all states are party to the CWC, the use of chemical weapons has not completely abated, and the chemicals and technologies that can be used to create these weapons are still, all around us.

As the Director-General of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons Fernando Arias said in an interview last month:

“…our mission to verifiably destroy declared stockpiles has a conceivable end point. But our mission to prevent the re-emergence of chemical weapons requires constant vigilance.”

Conferences like this one are a part of the ongoing work to reinforce the taboo against chemical weapons. In my talk today, I’m going to sketch out what the 1997 Chemical Weapons Convention is and what it has accomplished. But to understand where we are, we need to consider where we have been. So, I want to begin with a brief review of the history surrounding the development, use, and reactions to chemical warfare. Then I will talk about the CWC itself, what it does and the challenges the regime faces today.

The Use of Chemical Weapons and the Evolution of the Norm Against Them

The use of harmful chemicals in warfare, personal attacks, and assassinations dates back centuries, but the rise of industrial production of chemicals in the late 19th century opened the door to more massive use of chemical agents in combat.

The first major use of chemicals on the battlefield was in World War I when Germany released chlorine gas from pressurized cylinders in April 1915 on the front lines near Ypres in Belgium.

Ironically, this attack did not technically violate the 1899 Hague Peace Conference Declaration, the first international attempt to limit chemical agents in warfare, which banned only “the use of projectiles” designed to diffuse poison gases.

Later, both sides would employ chemical weapons. And with the more widespread introduction of mustard gases in 1917, chemical weapons and agents injured some one million soldiers and killed approximately 100,000 during World War I.

In the United States and Canada, the public was particularly shocked by the prevalence of ailments suffered by returning veterans due to their exposure to chemical agents. That revulsion would, in turn, lead to the push for the Geneva Protocol of 1925 which sought to ban the use of biological and chemical weapons in the field of conflict.

However, the Geneva Protocol does not regulate the production, research or stockpiling of these weapons. It allows nations to reserve the right to retaliate with chemical weapons should it be subject to chemical attack.

Unfortunately, many of the countries that joined would join belatedly and with major reservations. China, France, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom all joined in the 1920s. Others would not join until much later. Japan did not join until 1970 and the United States until 1975. While limited, the Geneva Protocol helped to establish an international norm against CW use.

The taboo, however, was not strong enough.

Between the two world wars, there were a number of reports of use of chemical weapons in regional conflicts:

- Morocco in 1923-1926

- Libya in 1930

- China in 1934

- Ethiopia in 1935-1940, and

- Manchuria in 1937-1942

After the end of World War II in 1945, several states, particularly the United States and the Soviet Union build up chemical weapons stockpiles as part of their Cold War standoff.

And there were sporadic chemical weapons attacks in regional wars, including in the Yemen war of 1963-1967 when Egypt bombed Yemeni villages, killing some 1,500 people.

There were major uses of chemical weapons by Iraq in the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq war and in Saddam Hussein’s bombing of the Kurds in Halabja in 1988. Saddam Hussein’s chemical attacks helped created a sense of urgency to the slow-moving CWC negotiations, which had begun in the early 1980s.

The failure of the United States in the 1980s to condemn the attacks against Iran undoubtedly emboldened Saddam Hussein. In response, other countries in the Middle East, particularly Syria, accelerated their chemical weapons programs.

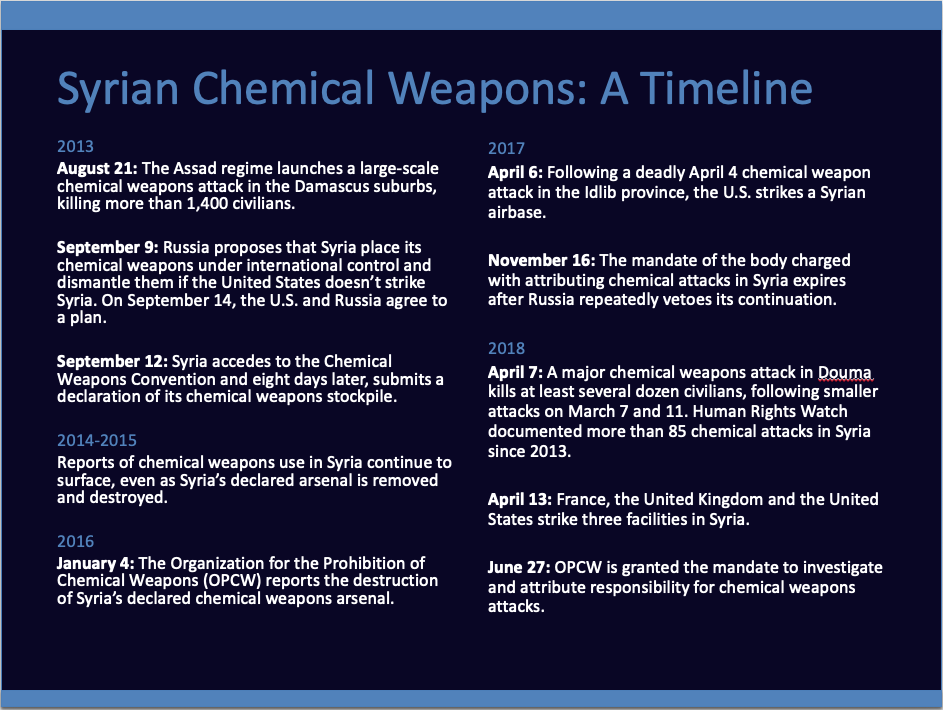

Since the Chemical Weapons Convention came into force in 1997, the most significant cases of chemical weapons use have –of course – been in Syria during its brutal civil war.

Chemical Weapons Use Since 1997

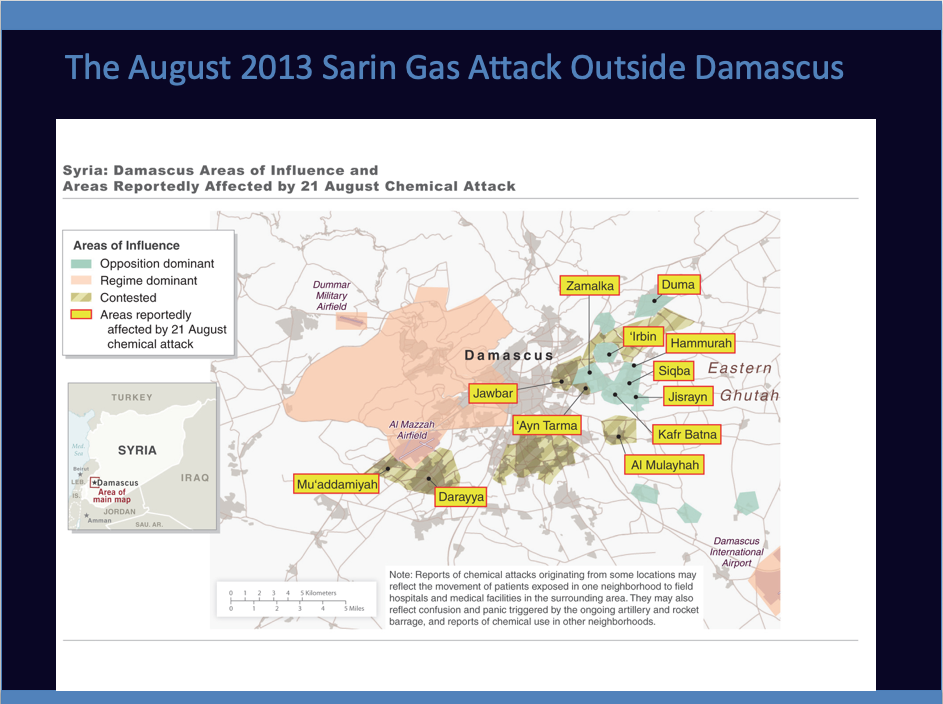

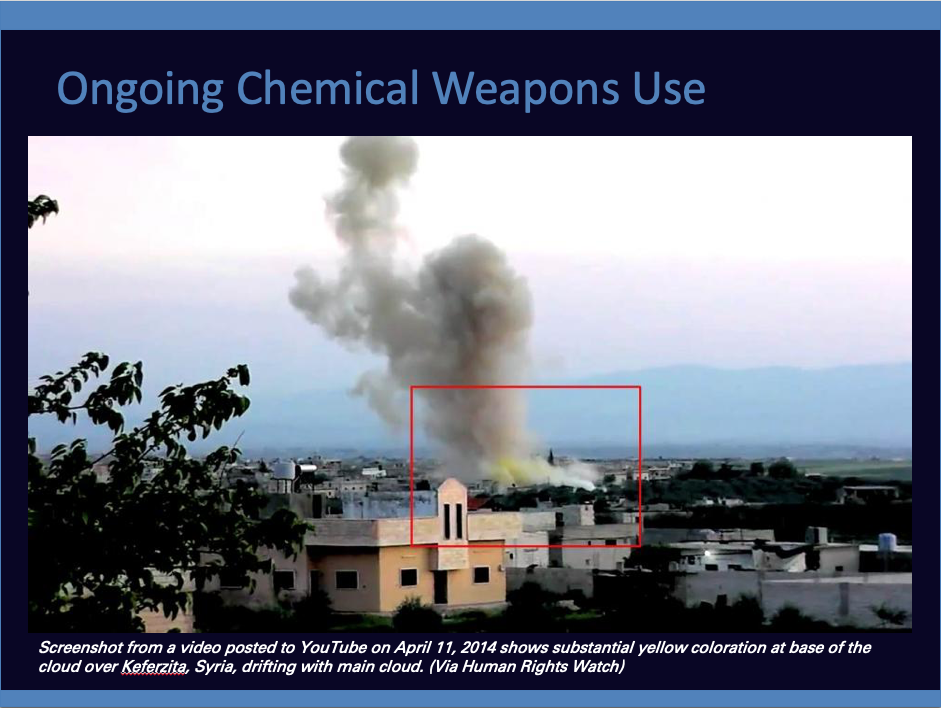

The Assad regime launched chemical attacks against opposition forces on numerous occasions beginning in 2012, including a massive Sarin attack in August 2013 that killed more than 1,400 people.

The Assad regime launched chemical attacks against opposition forces on numerous occasions beginning in 2012, including a massive Sarin attack in August 2013 that killed more than 1,400 people.

The UN-OPCW Joint Investigative Mechanism (JIM) found the Syrian government responsible for numerous other attacks, including in April 2014, March 2015, March 2016 and April 2017.

It also found the Islamic State responsible for chemical weapons attacks in August 2015 and September 2016.

Human rights observers continue to document further chemical weapons incidents in Syria.

In February 2017, North Korean agents used VX, a nerve agent, to assassinate Kim Jong-nam, the half-brother of North Korean leader Kim Jong-un in the airport in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

In March 2018, the Russia agents used a Novichok to assassinate a former Russian spy, Sergei Skripal, and his daughter in the UK. These most recent incidents and attacks over the past six years have severely tested the chemical weapons prohibition regime.

The Path to the 1997 Chemical Weapons Convention

Today that regime is centered around the CWC. But the path to the CWC was not easy or quick.

And it was by no means a fate accompli.

In 1974, the Soviet Union and the United States commenced bilateral discussions on reducing chemical weapons stockpiles.

Formal, multilateral negotiation began at the Conference on Disarmament in Geneva in 1980.

The questions the negotiators had to grapple with were not simple, some of them included:

- Should a new treaty just address certain American and Russian or Soviet stockpiles of nerve agents and mustard gas, or blister agents, as a first step towards a more comprehensive treaty?

- Should it be a global treaty?

- Should it ban just certain chemical agents and stockpiles that could be used for weapons or should it be a comprehensive ban? If so, what does that actually mean? How do you verify compliance?

- Also, how do you establish criteria that would enable you to distinguish between the toxic chemicals that we need to prohibit and those that are needed for peaceful purposes that and or that we simply don't have to worry about it?

Through the 1980s there were no major breakthroughs. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union began developing even more dangerous agents, the Novichoks, and it expanded the production program of the traditional chemical warfare agents.

Nevertheless, under Soviet Leader Mikhail Gorbachev, the Russians began to recognize and accept the need for mandatory onsite inspections as part of any global chemical weapons control regime.

Another important impetus was the engagement and support of the chemical industry. By the late-1980s, the industry had begun to realize that there might be a treaty and if so, they needed to get on board and make sure it would be something they could live with.

By 1989 these U.S.-Soviet negotiations produced a bilateral memorandum of understanding concerning verification and data exchange.

By 1989 these U.S.-Soviet negotiations produced a bilateral memorandum of understanding concerning verification and data exchange.

Finally, the CWC negotiations were concluded and the treaty was opened for signature in January 1993. The 65 ratifications needed for entry into force were achieved by April 1997.

The Chemical Weapons Convention

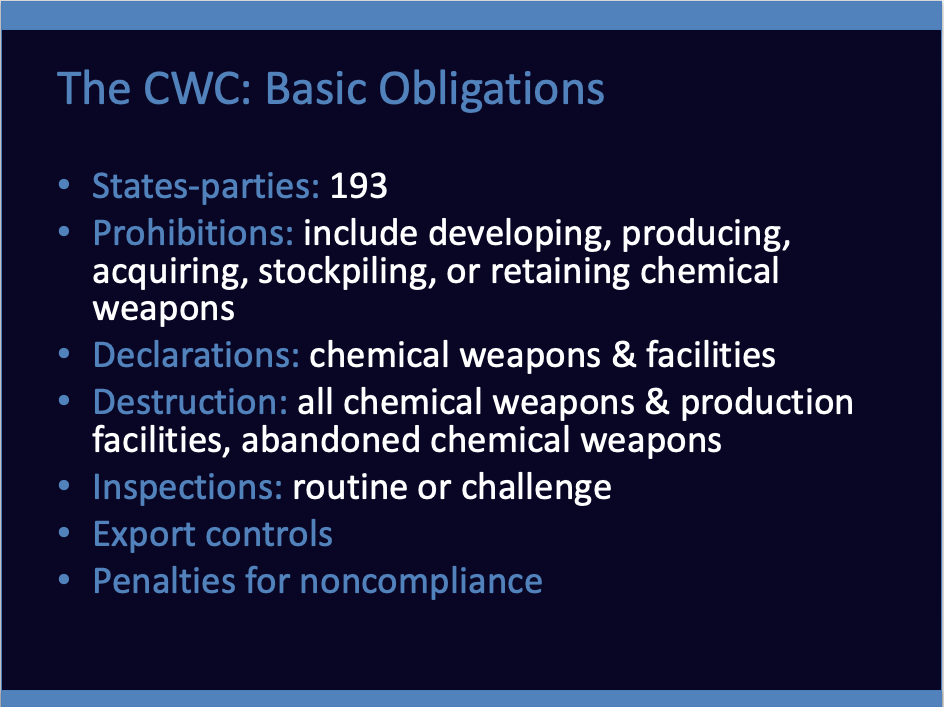

Today, the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) current has 193 states party and is implemented by the 500-person strong Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) headquartered in The Hague.

Israel has signed but has yet to ratify the convention. Three states have neither signed nor ratified the convention—Egypt, North Korea and South Sudan.

North Korea is perhaps the country of greatest concern. It has an estimated to possess a large arsenal of chemical weapons, likely over 5,000 metric tons, including mustard, phosgene, and nerve agents.

Syria is a party to the convention but is not in compliance.

The major work of the OPCW involves reviewing states-parties’ declarations detailing chemical weapons-related activities or materials and relevant industrial activities. After receiving declarations, the OPCW inspects and monitors, on an ongoing basis, states-parties’ facilities and activities that are relevant to the convention, to ensure compliance.

The major work of the OPCW involves reviewing states-parties’ declarations detailing chemical weapons-related activities or materials and relevant industrial activities. After receiving declarations, the OPCW inspects and monitors, on an ongoing basis, states-parties’ facilities and activities that are relevant to the convention, to ensure compliance.

The Chemical Weapons Convention mandates several key obligations:

- Developing, producing, acquiring, stockpiling, or retaining chemical weapons.

- The direct or indirect transfer of chemical weapons.

- Assisting, encouraging, or inducing other states to engage in CWC-prohibited activity.

- The use of riot control agents “as a method of warfare.”

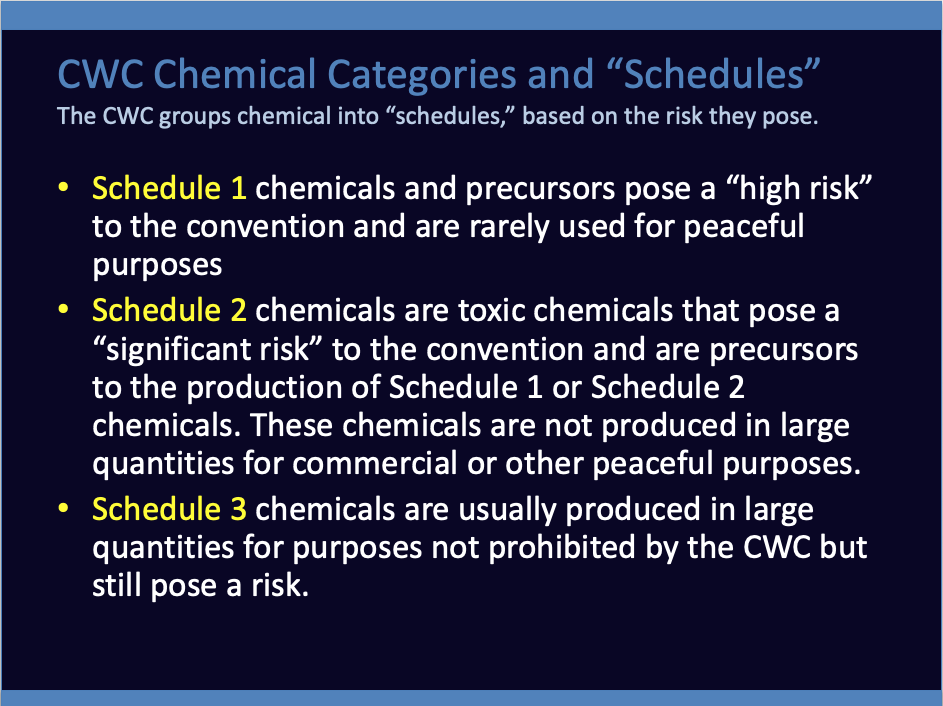

The CWC regulates chemical agents and the facilities that produce and store according to a set of categories and “schedules” listed in the treaty that based on the severity of risk they pose:

- Schedule 1 chemicals and precursors pose a “high risk” to the convention and are rarely used for peaceful purposes. These include VX and sarin.

- Schedule 2 chemicals are toxic chemicals that pose a “significant risk” to the convention and are precursors to the production of Schedule 1 or Schedule 2 chemicals. These chemicals are not produced in large quantities for commercial or other peaceful purposes. One example is phosgene.

- Schedule 3 chemicals are usually produced in large quantities for purposes not prohibited by the CWC but still pose a risk.

Destruction Requirements

The main result of the CWC over the past decade has been the verified destruction of the vast bulk of declared chemical weapons stockpiles and facilities. This has been an enormous undertaking.

Of the 193 states-parties to the CWC, eight had or still have declared chemical weapons stockpiles.

Of those eight countries, Albania, South Korea, India, Iraq, Syria, Libya and Russia have completed destruction of their declared arsenals.

As of December 2016, 90 of the 97 chemical weapons production facilities declared to the OPCW have either been destroyed or converted for peaceful purposes.

In addition, the OPCW has undertaken more than 5,000 inspections of more than 200 chemical weapons-related sites (stockpiles, former production facilities, and laboratories) and more than 1,100 chemical industry sites in 82 countries.

Russia and the United States

When Russia, the United States, and Libya declared that they would be unable to meet their final destruction deadlines by the treaty-mandated date of 2012, CWC state parties agreed to extend the deadlines with increased national reporting and transparency.

At the time the CWC was concluded, Russia had the largest declared stockpile with 40,000 metric tons at seven arsenals in six regions—oblasts and republics—of Russia.

The United States declared 28,577 metric tons at nine stockpiles in eight states and on Johnston Atoll west of Hawaii.

The U.S. Army initially planned to construct three centralized incinerators to destroy the U.S. chemical weapons stockpile, and early schedules optimistically showed the United States completing operations in 1994.

Congress subsequently banned transportation of chemical munitions on safety and security grounds, necessitating the current plan for a destruction facility at each of the nine U.S. sites at which chemical weapons are stored.

These concerns over transportation of chemical weapons and over incineration as a method of disposal led to major changes in the U.S. demilitarization program, adding to cost and creating schedule delays. In my view, however, the changes were worthwhile from a public health standpoint.

The United States aims to complete the process by 2023. It will have cost around $45 billion to complete.

The Successful CW Removal and Destruction Operation in Syria

In 2012, the Syrian government finally admitted what had been long suspected: that it had chemical weapons. Then, in August 2013, the Assad regime launched a Sarin attack with rockets into the Damascus suburb of Ghouta, which led U.S. President Barack Obama to threaten the use of force to try to destroy Assad’s chemical weapons arsenal in August and September of 2013.

This threat prompted Moscow to work with Washington to help compel Assad to join the CWC on September 12, 2013 and declare its chemical weapons stockpile and agree to a plan for its elimination soon after.

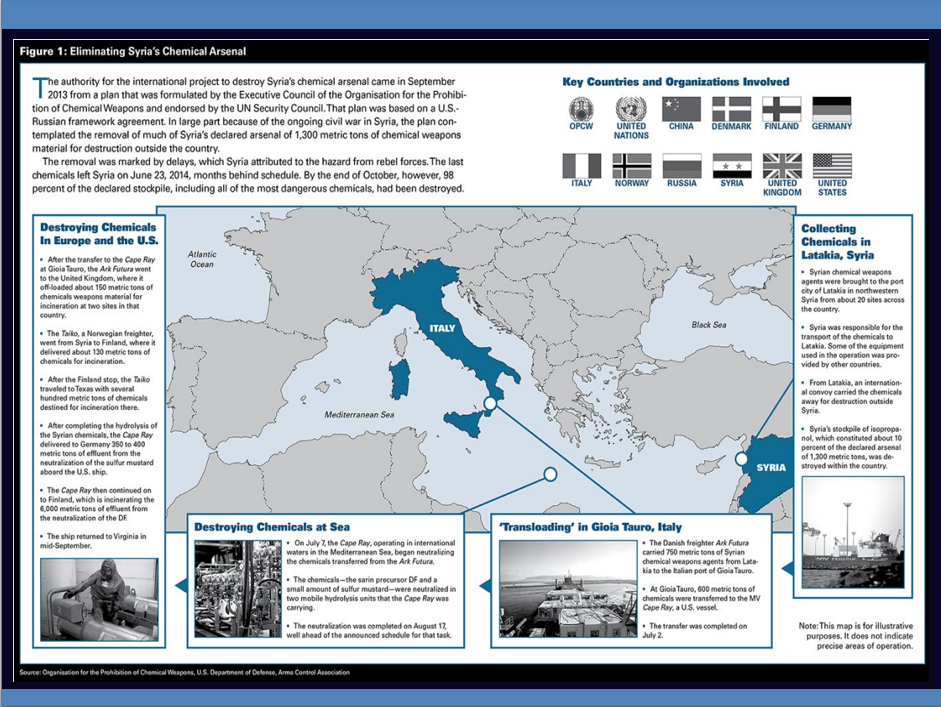

This led to an ambitious operation that led to the verified removal and elimination of Syria’s massive arsenal of 1,308 metric tons of chemical agents, storage and production facilities, and associated equipment under the auspices of the OPCW—all in the middle of the ferocious Syrian civil war.

The complex, multinational disposal operation was a major milestone that effectively eliminated the threat of further large-scale chemical weapons attacks by the Assad regime against the Syrian people and neighboring states.

The destruction processes were carried out through a remarkable operation on board the US Merchant Marine ship, Cape Ray, and in four countries – Finland, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

The OPCW announced that the entirety of Syria’s declared stockpile of 1,308 metric tons of sulfur mustard agent and precursor chemicals had been destroyed by January 2016.

However, reports continue to surface of chemical weapon use in Syria, raising questions about the accuracy of its initial declaration.

Current and Future Challenges to the CWC

CWC states parties and the OPCW have almost fulfilled the foundational goal of the CWC: the destruction of the world’s declared chemical weapons stockpiles. More than  96% have been destroyed under OPCW supervision.

96% have been destroyed under OPCW supervision.

Unfinished Business: But despite the global ban and the successful destruction work, we are still seeing the ongoing use of chemical weapons by states and by some terrorist networks, the remaining U.S. stockpile must be destroyed, and four more states, Egypt, Israel, North Korea, and South Sudan still need to join the convention.

- Destruction of the remaining U.S. Stockpile by 2023

- Universalization: North Korea and its est. stockpile of 5,000 tonnes of agent, and the Middle East

- Noncompliance and accountability

National Implementation: Another challenge is ensuring compliance with the treaty’s provisions on national implementation, meaning efforts to put in place effective regulations and export control mechanisms for chemical agents.

Adapting Verification System: The CWC verification regime also needs to be adapted to match verification resources to CW proliferation challenges. More than half of all OPCW inspections are still related to disarmament, limiting the ability of the organization to detect and deter proliferation. There is an increasing number of chemical production facilities that pose proliferation risks, such as flexible, multipurpose production plants.

Closing the Loophole on Riot Control Agents: Article II.9(d) of the Chemical Weapons Convention designates law enforcement, including domestic riot control, as a potentially acceptable purpose for the use of certain toxic chemicals.

However, the range of potentially permissible chemicals has not been established. This provides a possible loophole for the use and development of ever-more sophisticated agents for such purposes would work against the prohibition of chemical weapons. There are 39 countries pushing to close this loophole.

Developing A New Attribution Mechanism

The war in Syria has put the issue of attribution in the spotlight, particularly in instances where CWC member-state Russia, which is Syria’s ally, has used its UN Security Council veto to thwart investigations.

The independent OPCW-UN Joint Investigative Mechanism (JIM) has determined that chemical weapons were used by Syria and the Islamic State group, but Russia has blocked its renewal by the UN Security Council last year.

With new authority granted by CWC member-states earlier this year, Arias has said the OPCW is putting in place arrangements for the purpose of identifying entities responsible for chemical weapons use.

A special office for attribution will consist of a head of investigations and a few investigators and analysts who will be supported by existing Technical Secretariat expertise and structures.

“Those responsible [for chemical weapons attacks] should now have nowhere to hide and should be held accountable by the international community for breaking the global norm against chemical weapons,” Arias said last month in an interview with Arms Control Today.

The fourth review conference of the CWC will take place next month and member states will grapple with the ongoing task of ensuring that treaty obligations are fully implemented and that the CWC and the OPCW can be adapted in order to meet new challenges.

The fourth review conference of the CWC will take place next month and member states will grapple with the ongoing task of ensuring that treaty obligations are fully implemented and that the CWC and the OPCW can be adapted in order to meet new challenges.

To help the OPCW in that mission, governments and nongovernmental actors have a responsibility to ensure the chemical weapons prohibition regime has the necessary political and public support, and technical and financial resources to verify compliance – and hold accountable those who may violate the chemical weapons taboo.

I want to thank you for the chance to speak to you today. I look forward to your questions.