Volume 14, Issue 2, Feb. 16, 2022

Six years and a month ago, Jan. 16, 2016, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) went into effect. The JCPOA, which was concluded in July 2015 after years of intensive negotiations between Iran and the P5+1 (China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States), verifiably blocked Iran’s pathways to nuclear weapons and provided incentives for Tehran to maintain an exclusively peaceful nuclear program.

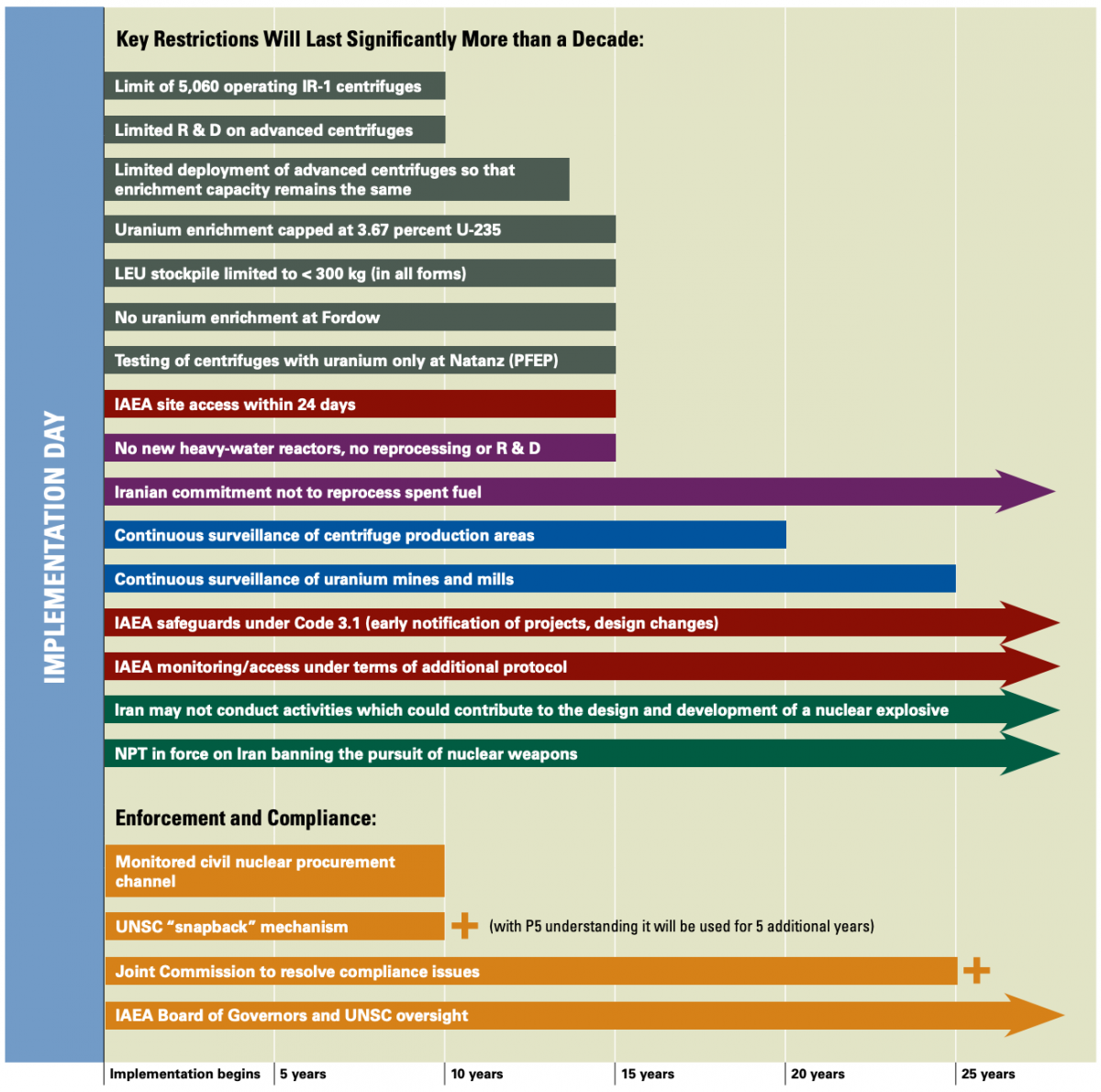

Taken together, the JCPOA’s nuclear restrictions dramatically rolled back Iran’s uranium-enrichment capacity and blocked its route to nuclear weapons using plutonium. It put in place an unprecedented multi-layered international monitoring regime that keeps every element of Iran’s nuclear fuel cycle under surveillance. The combination of restrictions and limits extended to at least one year the time it would take for Iran to amass a significant quantity of bomb-grade enriched uranium to fuel one bomb. The point was to ensure that if Iran decided to cheat, the international community would have enough time to detect it and take remedial action.

The relief from nuclear-related sanctions that Iran received in return for adhering to the nuclear restrictions and nonproliferation commitments were a strong incentive for Tehran to follow through on its obligations. Iran was complying with the JCPOA until the administration of former President Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew from the agreement in 2018 and reimposed and widened U.S. sanctions on Iran.

Trump’s exit from the JCPOA and his campaign to increase sanctions pressure on Iran ostensibly was intended to achieve a “better” or “more comprehensive deal.” Tragically, it not only failed to produce the promised results; it also opened the way for Iran to take steps beginning in 2019 to exceed the JCPOA’s nuclear limits and accelerate its capacity to produce bomb-grade nuclear material.

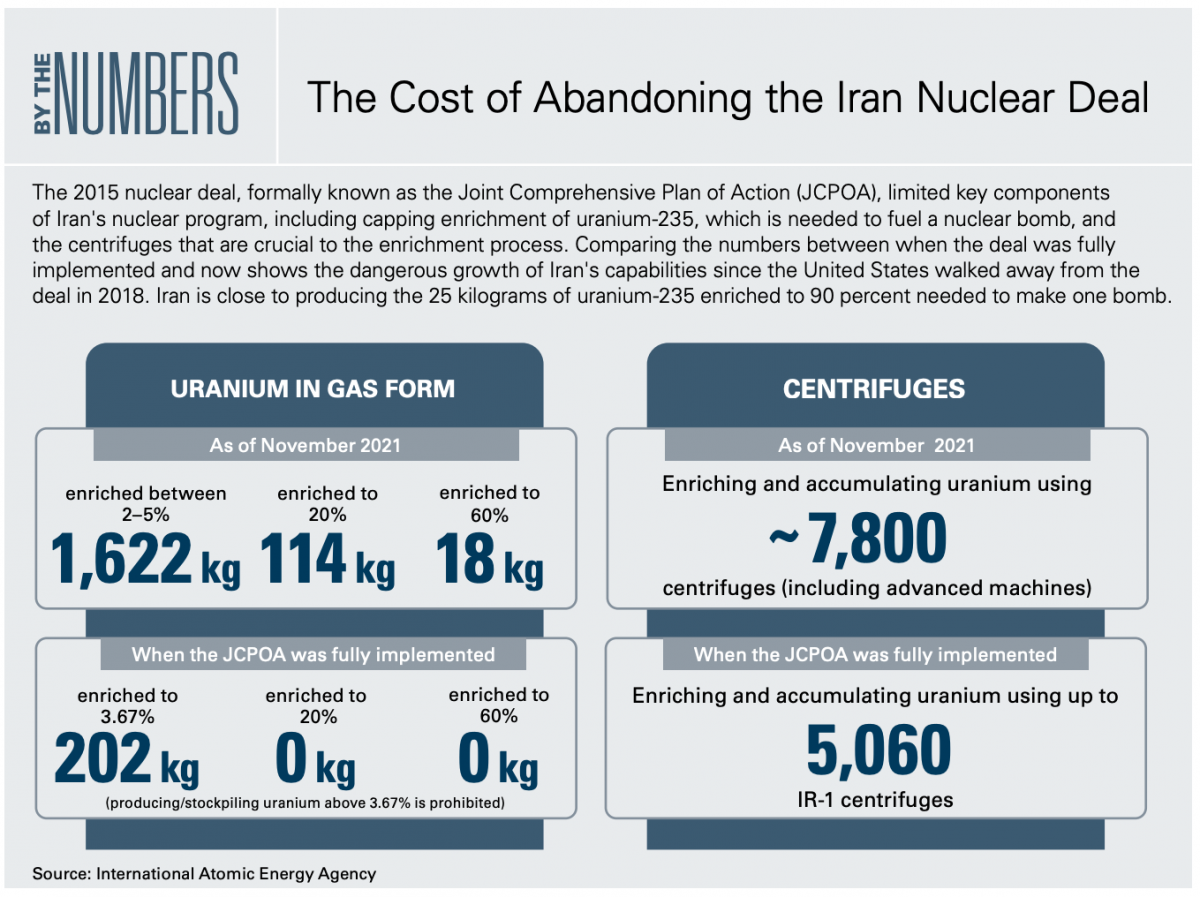

As a result of Trump’s policies, it is estimated that the time it would take Iran to produce a significant quantity (25 kg) of bomb-grade uranium (enriched to 90 percent U-235) is down from more than a year under the JCPOA, to approximately 60 days or less today.

Unless U.S., European, Russian, and Chinese negotiators can broker a deal to restore Iranian and U.S. compliance with the JCPOA, Tehran’s capacity to produce bomb-grade nuclear material will grow even further.

Unfortunately, some in Congress are threatening to try to block President Joe Biden and European allies from implementing the steps necessary to bring Iran back under the nuclear limits set by the JCPOA. If these opponents succeed, it is possible, and maybe even probable, that Iran would become a threshold nuclear-weapon state.

A prompt return to mutual compliance with the JCPOA is the best way to deny Iran the ability to quickly produce bomb-grade nuclear material. It would reinstate full international monitoring and verification of Iran’s nuclear facilities, thus ensuring early warning if Iran were to try to acquire nuclear weapons—and become the second state in the Middle East (in addition to Israel) with such an arsenal.

Trump’s Disastrous Policy Experiment

Trump campaigned against the JCPOA in 2016 and abruptly withdrew the United States from the JCPOA in May 2018 on the mistaken belief that if the United States rejected the agreement and increased sanctions pressure on Iran, it could coerce leaders in Tehran to renegotiate a “better deal.”

Two weeks after Trump announced the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA, the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA) quarterly report on Iran’s nuclear program found that Iran was implementing its nuclear-related commitments under the JCPOA.

In a speech at the Heritage Foundation in May 2018, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo promised to "apply unprecedented financial pressure on the Iranian regime," work with allies to deter Iranian aggression, and pursue a new deal based on 12 demands. These included requirements that Iran stop all uranium enrichment, end the proliferation of ballistic missiles and the development of nuclear-capable missile systems, and allow the IAEA to have "unqualified access to all sites throughout the entire country."

Four years later, it is clear that Trump’s decision to exit the JCPOA in an attempt to coerce Iranian leaders into a new deal that was more comprehensive and more favorable to the United States was an abject failure.

Iranian leaders, not surprisingly, refused to renegotiate the JCPOA. Worse still, Trump’s policy experiment isolated the United States from its European allies and opened the door for Iran to increase its capacity to enrich uranium.

In 2019, Iranian leaders began taking steps to improve the country’s nuclear capacity in violation of key limits set by the JCPOA. Among these were the accumulation of significant stockpiles of 20 percent and 60 percent enriched uranium-235, the deployment of significant numbers of advanced centrifuges, and the execution of some experiments, such as with uranium metal, that are relevant to weapons production. By 2020, Iran also began to impede the IAEA access necessary to monitor some of its sensitive nuclear activities.

Based on U.S. intelligence assessments, senior Biden administration officials are now warning that Iran could soon reach a “nuclear breakout” threshold, meaning that it could produce enough fissile material for one nuclear bomb in a matter of a weeks. At that point, Iran would need still to master several additional, complicated steps to build a deliverable nuclear arsenal that would likely take an additional year or more to complete. Nevertheless, Iran effectively would become a nuclear-weapon threshold state.

As Tamir Pardo, former director of the Israeli Mossad from 2011-2016, described Trump’s decision to exit the JCPOA at a Nov. 23, 2021, conference at Reichman University in Tel Aviv: “What happened in 2018 was a tragedy. It was an unforgivable strategy, the fact that Israel pushed the United States to withdraw from the [Iran nuclear] agreement 10 years too early. It was a strategic mistake.”

Meanwhile, Senator Chris Murphy said in a speech in the Senate Feb. 9: “… to the extent there was any silver lining of President Trump's decision [to exit the JCPOA], it's that it allowed us for four years to test the theory of the opponents, the theory of the critics … of the JCPOA.”

“It was a spectacular failure. It was a spectacular failure in multiple respects,” Murphy said.

Last Best Chance to Block Iran’s Path to a Bomb

Biden has vowed to try to repair the damage from Trump’s disastrous decision to exit the JCPOA. During the 2020 campaign, Biden pledged that “if Iran returns to strict compliance with the nuclear deal, the United States would rejoin the agreement as a starting point for follow-on negotiations.”

Now, after nearly a year of on-and-off indirect multilateral negotiations to restore U.S. and Iranian compliance with the JCPOA, the parties may be nearing a win-win solution. According to senior U.S. officials, the United States and Iran "are in the ballpark of a possible deal" to return to the 2015 nuclear agreement.

Other diplomats involved in the talks are also sounding more positive. “My assessment: we can finalize the exercise by the end of February, maybe earlier if nothing unexpected happens,” Russian negotiator Mikhail Ulyanov was reported to have said Feb. 11.

An agreement on an understanding to restore mutual compliance with the original terms of the JCPOA represents the most effective way to block Iran’s pathways to nuclear weapons. Under a restored deal, Iran would have to down blend and ship abroad the vast bulk of its stockpile of uranium enriched to 20 percent and 60 percent of U-235, dismantle most of its more advanced centrifuge machines, and limit the stockpile of enriched uranium to no more than 300 kilograms enriched to 3.67 percent U-235 until 2031, among other measures.

A return to mutual compliance with the original 2015 deal would reestablish long-term, verifiable restrictions on Iran's sensitive nuclear fuel cycle activities; many of the restrictions are scheduled to last for 10 years (until 2026), some for 15 years (until 2031), and some for 25 years or longer.

As importantly, the agreement would fully restore the layered international monitoring regime, including robust IAEA inspections under Iran's additional protocol to its comprehensive nuclear safeguards agreement. This will ensure that international inspectors have access indefinitely to any Iranian facility that raises a proliferation concern, including military sites. Under the JCPOA, Iran is required to provide early notification of design changes or new nuclear projects by Iran. (For a detailed assessment, see the August 2015 Arms Control Association report Solving the Iranian Nuclear Puzzle: The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.)

Summary of Nuclear-Related Commitments and Limitations of the JCPOA

A return to full compliance with the JCPOA would also provide a basis for further negotiations on a long-term framework to address Iran’s nuclear program and create space to engage Iran on other areas of concern, such as regional tensions and its ballistic missile program.

Most of Iran’s violations of the JCPOA are reversible and could be undone within a few months. However, some escalatory breaches--research and development, the operation of advanced centrifuge cascades, experiments with uranium metal--have resulted in Iran’s acquisition of new knowledge and expertise that cannot be reversed.

Consequently, if, under a restored JCPOA, Iran ever decides in the future to “breakout” and try to amass a significant quantity of fissile material for a nuclear weapon, it may take less than the 12-plus month timeline that existed in January 2016 when the deal was formally implemented.

The new “breakout” time would likely be between six months and somewhat less than 12 months, which is still far more than it will be if an understanding to restore compliance is not achieved.

As a result, a restored JCPOA would provide more than enough time to respond to an overt Iranian effort to build nuclear weapons. And with the intrusive IAEA monitoring and inspection regime mandated by the 2015 deal, Iran’s ability to attempt a covert dash for nuclear weapons would also be very limited and run a high risk of being detected.

In other words, a restored JCPOA would ensure months of warning if Iran ever decided to try to amass enough bomb-grade material for just one device; without the JCPOA, there likely would be no such warning time.

For these reasons and more, it is in the interests of the United States and the international community to achieve a prompt return to mutual compliance with the JCPOA.—DARYL G. KIMBALL, executive director