Volume 13, Issue 2, April 13, 2021

When former President Donald Trump took office in January 2017, the outgoing Obama administration warned that North Korea's nuclear program posed one of the most significant security challenges facing the United States. Four years later, the threat has grown.

Trump’s approach toward North Korea got off to a rough start with exchanges of fiery rhetoric and military threats, followed by high-profile summits that failed to produce lasting results or an effective negotiating process for denuclearization and peace-building on the Korean peninsula. In the absence of meaningful diplomatic progress, North Korea has continued to enhance its nuclear and missile arsenals and it remains one of the world’s most difficult and dangerous proliferation challenges.

Trump’s approach toward North Korea got off to a rough start with exchanges of fiery rhetoric and military threats, followed by high-profile summits that failed to produce lasting results or an effective negotiating process for denuclearization and peace-building on the Korean peninsula. In the absence of meaningful diplomatic progress, North Korea has continued to enhance its nuclear and missile arsenals and it remains one of the world’s most difficult and dangerous proliferation challenges.

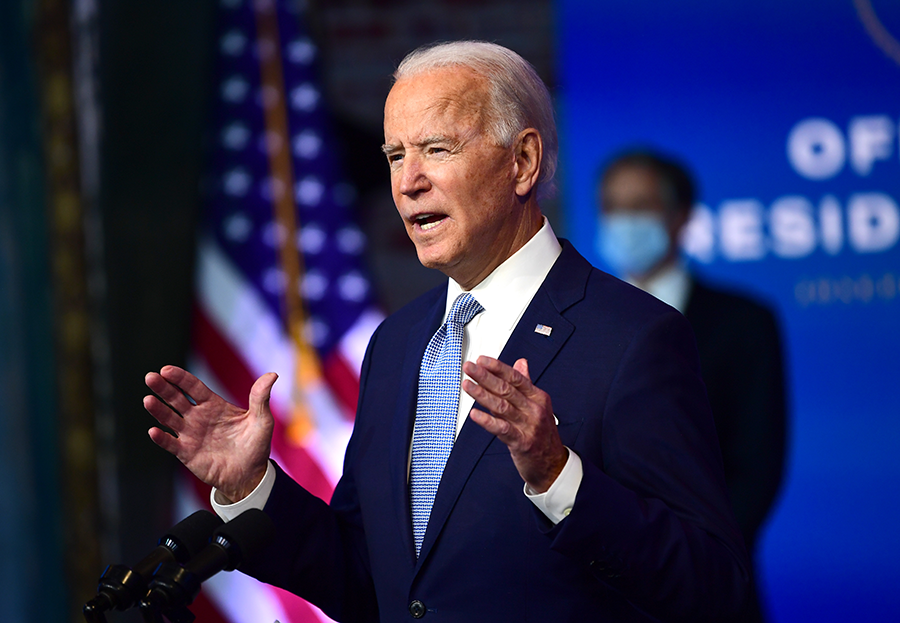

During his presidential campaign, President Joe Biden criticized Trump’s approach to diplomacy, including his decision to meet directly with North Korea’s leader Kim Jong Un, and promised to engage in “principled diplomacy” and “to offer an alternative vision for a non-nuclear future to Kim and the people of North Korea.”

Since taking office January 20, the new administration has been conducting a full review of U.S. policy toward North Korea. To date, key officials have offered few details about their strategy beyond reiterating that denuclearization will remain the end goal and that the United States intends to work closely with allies.

The administration’s North Korea policy review is a critical opportunity to forge a more effective U.S. approach toward the long-running effort to halt and reverse North Korea’s nuclear progress and reduce the risks of a major conflict. The Biden administration’s policy should take into account the positive and negative lessons from the Trump era as the United States seeks to work with regional allies and the international community to move closer to denuclearization on the Korean Peninsula.

The administration’s North Korea policy review is a critical opportunity to forge a more effective U.S. approach toward the long-running effort to halt and reverse North Korea’s nuclear progress and reduce the risks of a major conflict. The Biden administration’s policy should take into account the positive and negative lessons from the Trump era as the United States seeks to work with regional allies and the international community to move closer to denuclearization on the Korean Peninsula.

Building on the twin goals of denuclearization and peace established by Trump and Kim, Biden should adopt a more pragmatic, step-for-step approach that involves concrete actions on denuclearization in exchange for corresponding measures that address regional security dynamics and sanctions relief for North Korea.

North Korea’s Advancing Nuclear Weapons Program

During the first year of Trump’s presidency, North Korea accelerated its long-range missile testing, introducing three new systems: the Hwasong-12, an intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) tested six times (three tests failed), the Hwasong-14, an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), tested twice, and the Hwasong-15, an ICBM tested once. The Hwasong-15 is powerful enough to deliver a nuclear warhead to the entirety of the continental United States, although the accuracy, reliability, and survivability of the warhead during reentry remain questionable after just one test.

North Korea also tested its largest yield warhead—likely a two-stage hydrogen bomb—in September 2017. Since then, North Korea has not conducted any nuclear tests and did take steps as part of its diplomatic overture to the United States to destroy testing tunnels at the Punggye-ri test site in 2018. It is not clear if, or how quickly, North Korea could rebuild that nuclear test site, or if another exists.

There is considerable uncertainty about the size of North Korea’s stockpile of fissile material, but it has likely grown over the past four years. In 2017, North Korea's stockpile was estimated to include 20-40 kilograms of separated plutonium and about 250-500 kilograms of highly enriched uranium (HEU), according to Stanford physicist Sig Hecker, who visited North Korea’s uranium enrichment facility at Yongbyon in 2010. Leaked U.S. and South Korean assessments put the HEU stockpile close to 750 kilograms in 2017. According to a 2017 Defense Intelligence Agency assessment, North Korea’s stockpile of weapons-usable material is enough for up to 60 warheads but Pyongyang has likely only assembled around 20-30 nuclear devices. Satellite imagery suggests continued activity at the uranium enrichment facility and intermittent operations the five-megawatt reactor during the past several years, which was used to produce plutonium for the country’s nuclear weapons, at the Yongbyon nuclear complex, suggesting that North Korea continues to produce fissile material.

Following a spate of testing and increased U.S.-North Korea tensions in 2017, Kim claimed in his 2018 New Year’s address that North Korea’s nuclear forces are “capable of thwarting and countering any nuclear threats from the United States” and announced that North Korea would mass-produce nuclear warheads and ballistic missiles for deployment. He also opened the door for diplomacy with South Korea and later the United States—perhaps assessing that recent long-range missile tests would give him greater leverage in negotiations.

As part of the diplomatic overture, Kim declared an official testing moratorium for long-range missiles and nuclear explosive devices from April 2018. While that moratorium ended in December 2020, the country has not since tested any nuclear devices or long-range systems. North Korea resumed short-range ballistic missile testing in May 2020, after talks with the United States appeared to stall.

Since then, Pyongyang has introduced and tested several new short-range ballistic missiles. North Korea also displayed a new ICBM during an October 2020 parade that is larger than the Hwasong-15 and introduced two new ballistic missiles likely designed for a submarine, one during the October 2020 parade and one in January 2021. Kim also said in December 2020 that the country intends to pursue tactical nuclear weapons, indicating that North Korea will continue refining and developing new nuclear capabilities to meet the perceived security threats.

Lessons Learned from Trump-Kim Diplomacy

While North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs expanded

During his time in office, Trump met with Kim three times: first in Singapore in June 2018, then in Hanoi in February 2019, and briefly at the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea in June 2020. Although tension eased and North Korea has refrained from further long-range ballistic missile flight testing and nuclear testing since 2018, these summits, and the intermittent rounds of working-level talks between the leader-to-leader meetings, did not yield any sustained progress toward achieving the goals of denuclearization and peacebuilding on the peninsula. The United States did, however, gain further insights into North Korea’s negotiating position that should be useful for future diplomatic efforts.

During his time in office, Trump met with Kim three times: first in Singapore in June 2018, then in Hanoi in February 2019, and briefly at the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea in June 2020. Although tension eased and North Korea has refrained from further long-range ballistic missile flight testing and nuclear testing since 2018, these summits, and the intermittent rounds of working-level talks between the leader-to-leader meetings, did not yield any sustained progress toward achieving the goals of denuclearization and peacebuilding on the peninsula. The United States did, however, gain further insights into North Korea’s negotiating position that should be useful for future diplomatic efforts.

During the first summit, Trump and Kim signed a four-point Joint Statement, whereby the United States and

While the Singapore summit established the broad parameters and goals of the U.S.-North Korea diplomatic negotiations, it soon became apparent that Washington and Pyongyang preferred different processes to make progress. North Korea expressed a preference for a step-by-step approach, whereas the Trump administration appeared most focused on denuclearization and wanted North Korea to verifiably dismantle its nuclear weapons program before any sanctions were lifted. The two parties also did not share the same understanding of the agreed-upon goals, including what constitutes denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.

The differing interpretations over the processes and goals were compounded by mixed messaging and failure on both sides to sufficiently empower their negotiating teams. Despite the lack of progress and concrete action, Trump and Kim met for their second summit in Hanoi with cautious expectations for progress toward North Korea’s denuclearization.

In what appeared to have been a shift in the U.S. position, Steve Beigun, former deputy secretary of state and the U.S. special representative for North Korea, stated ahead of the second summit that the United States was prepared to move step-by-step with North Korea toward denuclearization while promoting peace on the peninsula.

Despite that shift, the Hanoi summit ended early and without agreement on subsequent steps. In a debrief of the meeting, Trump and Pompeo shared that the two sides had made progress, but said Trump rejected Kim’s call for sanctions to be entirely lifted in exchange for partial denuclearization. Pompeo remarked that Kim was “unprepared” to do more.

Countering the U.S. account of the meeting, North Korea’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Ri Yong Ho stated that North Korea had requested the partial removal of sanctions in exchange for a permanent halt of nuclear and ballistic missile testing and the full, verifiable, dismantlement of facilities at North Korea’s primary Yongbyon nuclear complex. Trump reportedly demanded “one more thing” atop North Korea’s proposal, which some have speculated could have been a facility outside of Yongbyon that is part of North Korea’s uranium enrichment program.

In April, Trump remarked that while he preferred a “big deal” with North Korea to “get rid of the nuclear weapons,” the door for “various small deals” remained open. Kim told the North Korean Supreme People’s Assembly April 12 that he would be willing to meet with Trump “one more time” if Washington proposed the summit, but said the United States would have to have the “right stance” and “methodology.” He called for Trump to “lay down unilateral requirements and seek constructive solutions.”

Trump and Kim met briefly one final time in June 2019 at the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea and agreed to restart working-level negotiations. Following that meeting, in September 2019, North Korea’s First Vice Minister Choe Son Hui issued a statement suggesting that North Korea was interested in continuing talks, provided that the United States offered “a proposal geared to the interests of the DPRK and the U.S.” Trump remarked shortly thereafter that he was open to a “new method” for talks with North Korea, suggesting a softening of the U.S. stance toward sanctions relief.

Working-level talks began in October 2019 in Stockholm, Sweden, and ended shortly thereafter. Ahead of the meeting, North Korea’s chief negotiator Kim Myong Gil praised Trump for taking a more flexible approach and suggested that “second thought” be given to the possibility of a “step by step solution starting with the things feasible first while building trust in each other,” likely referring to North Korea’s preference for an incremental approach that exchanges steps on denuclearization for actions by the United States to lift sanctions and address Pyongyang’s security concerns. After talks commenced, however, he said the U.S. came with “empty-handed” proposals that “greatly disappointed [the North Korean delegation] and sapped our appetite for negotiations.”

Trump administration reportedly offered North Korea time-bound, limited sanctions relief in exchange for concrete, verifiable steps to halt activities at Yongbyon during the meeting, but talks fell apart on the second day and North Korea did not accept the invitation to resume negotiations. Kim said the U.S. position demonstrated the United States’ unwillingness to “solve the issue”

Nearly two years of off-and-on summit diplomacy between the United States and North Korea were ultimately unsuccessful in leading to concrete action to advance the goals agreed to in Singapore. Disagreements over sequencing, particularly if and when sanctions relief should be offered, and the scope of each sides’ respective actions could not be resolved at the leader-level summits.

The Trump-Kim diplomatic process also failed because the two sides did not establish and maintaining a regular dialogue between high-level meetings. Such working-level engagement provides a greater opportunity to share and test concrete proposals and to pave the way for leadership-level summits to produce more tangible outcomes.

Consistent working-level talks are also necessary to build trust and rapport between negotiating parties. Working-level negotiating teams must also have the support from leadership to be effective, but critical mixed messages from Trump and other senior administration officials, including his National Security Advisor John Bolton, about the goals of the negotiations undercut the credibility of working-level negotiators, like Steve Beigun. On the North Korean side, Kim Jong-un did not appear to empower the negotiating team to discuss in any level of detail the country’s nuclear program slowed preparation for the Hanoi meeting.

Recommendations for a More Effective U.S. Policy

The North Korea policy review that the Biden administration is undertaking is not simply a new U.S. administration’s opportunity to set the stage for future talks and signal to Pyongyang the U.S. approach for the next four years—it is much more. Given that North Korea may be on the cusp of significant advancements in its capability to deliver nuclear weapons using a variety of short- and long-range ballistic missiles, the next four years may be the last best chance to freeze and begin to roll back its growing nuclear capabilities and the threat they pose to regional and international security.

The mixed results of the United States’ policies toward North Korea throughout the Obama and Trump administrations offer four sets of key lessons for reshaping the approach under Joe Biden in ways that produce more meaningful and lasting outcomes.

1. The Limits of Sanctions

Sanctions have played a significant role in Biden’s predecessors’ North Korea policy. Former Presidents Trump,

North Korea has demonstrated a considerable tolerance for economic pain and skill in evading sanctions. In recent years, North Korea has become increasingly more adept and creative in its efforts to sidestep sanctions and it has shown that it is unwilling to make unilateral concessions in response to tougher U.S. or UN sanctions.

Furthermore, enforcement and implementation of UN and U.S. sanctions measures have been spotty, especially after Trump prematurely declared that he had achieved success in erasing the North Korean threat following his first summit with Kim Jong-un.

As a result, Washington cannot depend on sanctions pressure alone to push Kim to the negotiating table, especially in the absence of stronger support from regional allies, particularly China, which is North Korea’s largest remaining trading partner.

The Biden administration is unlikely to lift any sanctions absent significant moves from North Korea that roll back its nuclear program, but the North Korea policy review could signal to Pyongyang that there is a credible offramp from sanctions through concrete steps to halt, reverse, and eventually dismantle key nuclear and missile capabilities. This could include partial relief early in the process in exchange for concrete actions from North Korea. The Biden administration’s North Korea policy review should also consider how to better implement humanitarian exemptions for sanctions and support inter-Korean projects.

2. Reaffirming the Goals of the Singapore Summit

The United States’ diplomatic strategy should include reaffirming the objectives of the 2018 Singapore Summit joint statement and indicating clearly that the United States will engage in meaningful talks toward achieving those objectives without preconditions.

The Singapore goals envision a transformed relationship between the United States and North Korea that includes “complete denuclearization of the Korean peninsula” and “a lasting and stable peace regime on the Korean Peninsula.” Given the role that nuclear weapons play in North Korea’s security calculus, transforming the U.S.-North Korea relationship and the security environment will be critical for moving toward denuclearization.

The Singapore summit declaration may also be North Korea’s preferred starting point. For Kim, the Singapore meeting was a considerable political achievement. Additionally, North Korea has long viewed denuclearization as encompassing the entire peninsula and including elements of the U.S. extended deterrence over North Korea. The Singapore summit declaration recognizes that regional security and stability directly impact the path to denuclearize and folds in addressing Pyongyang’s security concerns as part of a more holistic set of negotiations.

Unfortunately, the Biden administration has already stoked some confusion by calling for “denuclearization of the Korean peninsula” and “denuclearization of North Korea” interchangeably. This risks sending the wrong message to Pyongyang about U.S. intentions, as the denuclearization of North Korea suggests that the Biden administration is focused on dismantling the country’s nuclear weapons program and not taking into account Pyongyang’s understanding of the necessary conditions for denuclearization. Hopefully, once the policy review is completed, the Biden administration will demonstrate more consistent messaging.

Some experts favor abandoning the goal of denuclearization, arguing that North Korea does not intend to give up its nuclear weapons, and

The arms control versus denuclearization debate, however, sets up a false choice. U.S. policy can retain denuclearization as a long-term goal while pursuing arms control-like agreements that build toward verifiable dismantlement of North Korea’s nuclear weapons program.

Retaining denuclearization as the long-term goal is important for both North Korea-specific policy purposes and reinforcing a nuclear nonproliferation regime writ large.

This does not mean, however, that the United States should pursue a comprehensive denuclearization agreement at the onset. A series of smaller deals that prioritize reducing risk and preventing North Korea from further refining and developing its nuclear and missile programs will lead toward denuclearization while building confidence in the process and contributing to stability in the region.

3. A Reciprocal Step-by-Step Approach

The Biden administration should also make clear that the United States will pursue a reciprocal, step-by-step diplomatic strategy that rewards concrete actions toward the denuclearization of the Korean peninsula with sanctions relief and mutual confidence-building measures that reduce the risk of conflict and address North Korea’s security concerns.

There is value in working in phases rather than trying to negotiate a comprehensive agreement risks the talks ending without any concrete actions that reduce nuclear risk and increase stability in the region.

Overall, the essence and strength of this step-by-step approach is the flexible choreography and yet firm direction toward a more peaceful, stable, and prosperous Korean peninsula that not only deals with North Korean nuclear and missile production but also addresses North Korea’s security concerns. A step-by-step process also stands a better chance for maintaining continuity and momentum between changing administrations, whereas if negotiators fail to reach a comprehensive deal, talks may falter in the transition to a new administration.

There are reasons to believe that this approach will still be

Further, this step-by-step policy approach may garner more support from China—which the Biden administration has indicated it wants to encourage— as it aligns with Beijing’s approach and interests. China and North Korea released a joint statement March 22 calling for such a process.

As a first step, the Biden administration could explore an agreement based on the broad outlines of the proposal that North Korea put on the table in Hanoi: the verified dismantlement of Yongbyon and a cessation of nuclear and long-range ballistic missile testing in exchange for partial UN sanctions relief. Dismantlement of Yongbyon would be a significant step toward denuclearization that prevents North Korea from producing further plutonium for nuclear weapons, as well as tritium, which can be used to boost the explosive yield of two-stage nuclear bombs. Partial UN sanctions relief could include putting in place time-bound caps for trade in certain sectors that would offer meaningful relief to North Korea, but snap back into place if the talks become stalled or if Pyongyang does not deliver on its denuclearization commitments.

There are several other actions—both larger and smaller—that the United States could pursue as a meaningful, concrete first step that would reduce risk and prevent further qualitative and/or quantitative advancements to North Korea’s nuclear arsenal. These could include:

- halting of fissile material production, which can be verified using remote monitoring technologies;

- reinstating North Korea nuclear and long-range ballistic missile test moratoriums, and expanding it to include medium-range systems and rocket motors;

- halting the production of nuclear-capable ballistic missiles;

- verifying the closure of testing sites like the Punggye-ri; and

- securing North Korean signature of the 1996 Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty.

In response, United States, in coordination with allies and members of the UN Security Council, can take actions to address North Korea’s trade and security concerns, scaled to match Pyongyang’s actions. These include:

- providing partial sanctions relief, including measures in United Nations Security Council resolutions,

- modifying joint U.S.-South Korea military exercises so they do not involve force movements that appear to be part of preparations for a rapid strike at North Korean leadership targets,

- establishing a joint statement declaring an end to the Korean War and/or initiating discussions on the negotiations of a formal peace treaty,

- resuming inter-Korean trade and cultural exchange projects which can improve inter-Korean trade, and

- providing assurances that the United States will not threaten or conduct a nuclear strike on North Korea,

Given that North Korea views its nuclear arsenal as integral to its security, addressing the regional threat environment should be an integral part of the reciprocal actions the United States puts on the table, alongside sanctions relief, in exchange for verifiable actions toward denuclearization.

North Korea has signaled on many occasions that it views certain exercises as provocative. A spokesman for North Korea’s State Affairs Commission pointed Nov. 13, 2019, to routine military training exercises as a factor in “the repeating vicious circle of the DPRK-U.S. relations.” Modifying US-South Korean joint exercises and pursuing a formal peace treaty would reduce tensions and begin addressing the security concerns that underpin North Korea’s reliance on nuclear weapons.

Bottom Line

While Biden faces an array of complex foreign and domestic challenges, early proactive outreach to North Korea must be a priority. While Kim may not yet be ready to engage in talks, particularly while the Covid-19 pandemic continues, the United States must continue to send the message that diplomacy without preconditions is on the table and that Washington is ready to provide meaningful reciprocal actions in exchange for concrete steps to reduce nuclear risk.—SANG-MIN KIM, Scoville Peace Fellow, and JULIA MASTERSON, research associate