Volume 11, Issue 9

Updated January 29, 2020

(This issue brief was originally published December 17, 2019. It was updated to reflect Iran's fifth breach of the 2015 nuclear deal.)

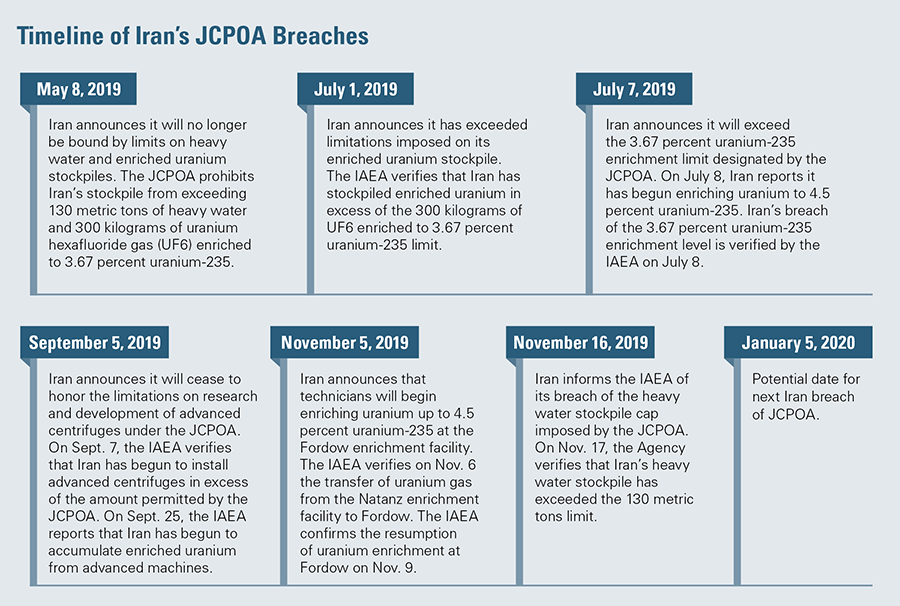

Since Iranian President Hassan Rouhani announced in May 2019 that Tehran would reduce compliance with the 2015 nuclear deal, Iran has breached limits imposed by the agreement every 60 days. While none of the violations pose a near-term proliferation risk, taken together, Iran’s systematic and provocative violations of the nuclear deal are cause for concern and jeopardize the future of the deal.

Under the nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), Iran is subject to stringent limitations on its nuclear program and intrusive monitoring by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). In return, the P5+1 (the United Kingdom, France, Russia, China, Germany, the EU and, formerly, the United States) committed to waiving sanctions imposed on Iran. United Nations Security Council also endorsed the deal in Resolution 2231 (2015), which lifted UN sanctions on Iran and levied restrictions on Iranian conventional arms and ballistic missile transfers.

Despite acknowledging Iran’s compliance with the multilateral agreement, U.S. President Donald Trump withdrew from the JCPOA in May 2018. A White House press release issued May 8, 2018, condemned the Iran deal and cited Iran’s “malign behavior” and its support for regional proxies as an impetus for the U.S. withdrawal. Trump also ordered the reimposition of sanctions that had been lifted or waived under the JCPOA, violating U.S. obligations under the accord. Since May 2018, the Trump administration continues to aggressively deny Iran any benefit of remaining in compliance with the nuclear deal and is pressing the P4+1 to join Washington’s pressure campaign.

The P4+1 continues to support the JCPOA and engage in efforts to maintain legitimate trade with Iran, but the extraterritorial nature of the U.S. sanctions eliminated most of the benefits to Tehran envisioned by the deal. The P4+1’s failure to deliver on sanctions relief in the year after Trump’s announcement drove Rouhani to announce that Iran would begin violating the JCPOA, and would continue to breach limits every 60 days, until oil sales, banking transactions, and other areas of commerce were restored.

Since Rouhani’s announcement in May 2019, Iran has breached JCPOA limits on uranium enrichment, research and development on advanced centrifuges, and stockpile size. When announcing the fifth breach in January 2020, Iran stated that its uranium enrichment program no longer faced any restrictions. To date, the actions Iran has taken in violation of the JCPOA appear to be calculated steps designed to increase pressure on the P4+1 to deliver on sanctions relief and are not indicative of a dash to a nuclear bomb. While concerning, the breaches do not pose a near-term risk and are quickly reversible, supporting Rouhani’s assertion that Iran will return to compliance with the JCPOA if its conditions are met. Iran’s continued implementation of the more intrusive monitoring and verification mechanisms put in place by the JCPOA further support the assessment that Iran is seeking leverage in negotiations with the P4+1 and is willing to return to compliance if its demands are met, not dashing for a bomb.

1) Breaching the Stockpile Limits on Enriched Uranium and Heavy Water

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani declared in a May 8 speech that Tehran would no longer observe JCPOA restrictions on its enriched uranium and heavy water stockpile. Rouhani said the decision was a reaction to the U.S. reimposition of sanctions and that “once our demands are met, we will resume implementation.”

The JCPOA caps Iran’s stockpile at “under 300 kg of up to 3.67% enriched uranium hexafluoride (UF6) or the equivalent in other chemical forms.” 300 kilograms of UF6 equates to 202.8 kilograms of uranium (Annex I, Section A, para. 7).

On July 1, Iran’s Foreign Minister, Javad Zarif, announced that Iran exceeded that limit. A report released by the IAEA on the same day verified that Iran’s stockpile of uranium enriched to 3.67 percent uranium-235 totaled 205.0 kilograms, constituting Tehran’s first breach of the JCPOA.

Iran has continued to grow its stockpile since first breaching the limit in July. Most recently, the IAEA reported in November that Iran’s stockpile had reached 372.3 kilograms of uranium enriched to less than 4.5 percent.

At present, Iran’s enriched uranium stockpile continues to pose a relatively low proliferation risk, and its breach of the JCPOA stockpile limits has only marginally shortened the one-year nuclear breakout time established by the deal. To manufacture one nuclear bomb, Iran would need to produce roughly 1,050 kilograms of low-enriched uranium (under five percent uranium-235) and would then need to further enrich this material to weapons-grade (greater than 90 percent uranium-235).

However, the head of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, Ali Salehi, has indicated that Iran intends to produce close to five kilograms of enriched uranium per day. If true, Iran’s stockpile could hit 1,050 kilograms in less than four months. The breakout time would be longer, however, as additional time would be needed to enrich the material to weapons-grade. The time it would take to reach weapons-grade would depend on how many centrifuges are use and the efficiency of the machines.

Iran did not breach the 130 metric ton heavy water limit until November. The IAEA reported Nov. 17 that Iran’s stockpile measured 131.5 metric tons. Heavy water, which contains the isotope deuterium, is used as a coolant in some types of reactors, including the Arak heavy water reactor currently under construction. Heavy water itself does not pose a proliferation risk. However, heavy water reactors are generally considered a proliferation-sensitive technology because they typically produce higher amounts of weapons-grade plutonium-239 in the spent fuel.

Both of the stockpile breaches are quickly reversible. Iran could easily blend down or ship out excess low-enriched uranium and sell or store overseas the excess heavy water.

If the 40-megawatt Arak reactor had been completed as originally designed, it would have produced enough weapons-grade plutonium for two bombs on an annual basis. Under the JCPOA, Iran agreed to collaborate on rebuilding and modifying the Arak heavy water reactor to mitigate the proliferation risk. (Annex I, Section B) Under the modified design, the 20-megawatt reactor will run on low-enriched uranium, resulting in the production of about a quarter of the plutonium-239 necessary to produce a nuclear weapon on an annual basis. Tehran also agreed to ship out the spent fuel from the reactor for 15 years.

In January 2016 the IAEA verified that Iran had removed and cemented the original reactor core and has subsequently reported that Tehran has not resumed construction on the reactor based on its original design. Iran threatened in July 2019 to resume activities at the heavy water reactor based on the original design, but given that work modifying the reactor continues, there is no proliferation risk posed by Iran’s breaching of the heavy water stockpile limit at this time.

If the United States ends sanctions waivers allowing cooperative work on the Arak reactor to continue, Iran may follow through on its threat to abandon modifications and resume construction on the original design. If so, it would still take years for the reactor to become operational.

2) Breaching the Limit on Uranium Enrichment

Behrouz Kamalvandi, Spokesman of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI) announced July 7 that Iran would exceed the 3.67 percent uranium-235 enrichment level imposed by the JCPOA for 15 years. (Annex I, Section F, para. 28). On July 8, Kamalvandi told reporters that Iran began enriching uranium to about 4.5 percent uranium-235.

The IAEA verified that Iran was enriching uranium hexafluoride gas (UF6) to greater than 3.67 percent uranium-235 at the Natanz Fuel Enrichment Plant July 8, according to an agency report released that day.

The IAEA’s Nov. 11 report indicates that Iran’s enriched uranium remains at or below a 4.5 percent uranium-235 enrichment level, and that of Iran’s 372.3-kilogram low-enriched uranium stockpile, about 159.7 kilograms have exceeded the JCPOA-designated 3.67 percent enrichment limit.

The extent to which this modest increase in the enrichment level poses a proliferation risk is dependent upon how many centrifuges are used for higher-level enrichment and how much material is stockpiled.

Uranium-235 is a fissile isotope that occurs in only 0.07 percent of naturally occurring uranium. Uranium enrichment is a process through which natural uranium, which is 99.3 percent uranium-238, after conversion into gaseous uranium hexafluoride (UF6), is enriched to increase the concentrations of uranium-235. Uranium enriched to less than five percent is typically used to fuel nuclear power reactors.

A sophisticated uranium-based nuclear bomb requires approximately 12 kilograms of weapons-grade uranium (greater than 90 percent uranium-235). The IAEA uses 25 kilograms of weapons-grade uranium as the threshold for a “significant quantity,” and given that Tehran has never produced HEU for a bomb, this higher threshold is likely a more accurate estimate of what Iran might need if it chose to pursue a nuclear weapon.

A large stockpile of low-enriched uranium, once amassed, would shorten the time needed to enrich up to weapons-grade. The quantity that Iran has produced to date is not considered a near-term proliferation risk. Though provocative, this breach is easily reversible and did not substantially shorten the one-year window of time that it would take for Iran to produce enough fissile material for a nuclear weapon.

3) Abandoning Limits on Advanced Centrifuges

On Sept. 5 Iranian President Hassan Rouhani declared that “all of our commitments for research and development under the JCPOA will be completely removed by Friday.”

Under the nuclear deal, for 10 years, Iran’s enriched uranium stockpile is limited to output from 5,060 first-generation IR-1 centrifuges at the Natanz Fuel Enrichment Plant. The deal allows for Iran to continue research and development (R&D) on a limited number of advanced machines for the first 10 years, so long as such activities do not contribute to an accumulation of enriched uranium.

Specifically, for 10 years after implementation (or until the year 2025), Iran is permitted to conduct R&D on a specified number of IR-4, IR-5, IR-6, and IR-8 model centrifuges. R&D on cascades of up to 30 IR-6 and IR-8 centrifuges is only permitted 8.5 years after the deal’s implementation (Section G, para. 35-37).

The IAEA verified on Sept. 7 that Iran had installed or was in the process of installing 22 IR-4 centrifuges, one IR-5 centrifuge, 30 IR-6 centrifuges, and three IR-6s centrifuges. On Sept. 8, Iran alerted the Agency of its intention to install piping to accommodate two cascades: one of 164 Ir-4 centrifuges and one of 164 IR-2m centrifuges.

On Sept. 25, the IAEA observed that three cascades: one of 20 IR-4 centrifuges, one of 10 IR-6 centrifuges, and one of 20 IR-6 centrifuges “were accumulating, or had been prepared to accumulate, enriched uranium.” The IAEA also reported that the installation of 164 IR-2m centrifuges was ongoing. The IAEA later verified in November that operational cascades of 164 IR-2m and 164 IR-4 centrifuges were accumulating enriched uranium.

In October, Iran alerted the IAEA of its intention to install additional advanced machines, including new IR-7, IR-8, IR-9, and IR-s model centrifuges. Iran is permitted under the JCPOA to develop new machines using computer modeling but requires approval from the body set up by the accord to oversee its implementation before testing. Iran does not appear to have obtained that permission. Tehran indicated that these new machines, once installed, would be used to further accumulate enriched uranium.

Taken together, Iran’s actions breached both the R&D testing limitations and the prohibition on accumulating enriched uranium from advanced machines imposed by the JCPOA.

With advanced machines, Iran can enrich uranium faster and more efficiently. However, Iran’s initial introduction of a limited number of advanced machines for research and for low-enriched uranium production did not, by itself, constitute a near-term proliferation risk. Similar to Iran’s earlier steps to breach the accord, this action is also quickly reversible, should Iran choose to return to compliance with the accord. Iran will have gained knowledge about advanced centrifuge performance that cannot be reversed, but the advanced machines can be quickly dismantled and put in storage under IAEA seal.

Whether enrichment using advanced machines will pose a long-term proliferation risk is dependent upon the number of machines used and their efficiency, the level of enrichment, and the amount of enriched uranium accumulated. It appears that Iran intends to continue installing and operating advanced machines, but the efficiency of the advanced models is not reported by the IAEA.

The introduction of additional advanced centrifuges, coupled with enrichment to levels higher than 4.5 percent uranium-235 or resulting in a substantial accumulation of low-enriched uranium, would pose a heightened proliferation risk. At present, however, due to the relatively small size of Iran’s enriched uranium stockpile and the small number of operating advanced centrifuges, enrichment using these models does not significantly shorten the time it would take for Iran to produce enough fissile material for a nuclear weapon.

4) Resuming Enrichment at Fordow

Rouhani announced Nov. 5 that Iranian technicians would begin injecting uranium hexafluoride gas (UF6) into centrifuges at the Fordow facility. Specifically, Behrouz Kamalvandi said that Iran would enrich uranium using 696 of the IR-1 centrifuges at Fordow and use the remaining 348 for the production of stable isotopes. Iran requested that the IAEA monitor the resumption of enrichment.

Under the JCPOA, Iran is permitted to conduct uranium enrichment only at the Natanz Enrichment Facility. Fordow, where Iran once enriched uranium up to 20 percent uranium-235, is to be converted into a nuclear, physics, and technology center in accordance with the deal (Annex I, Section H). The deal requires the P5+1 to assist Iran with the conversion and the Russian nuclear energy company, Rosatom, was working with Tehran on stable isotope production.

According to a Nov. 11 IAEA report, a cylinder of uranium hexafluoride (UF6) was transferred from Natanz to Fordow Nov. 6. On Nov. 9, the Agency verified that Iran had fed UF6 into two cascades of IR-1 centrifuges and commenced uranium enrichment at Fordow.

The IAEA reported that Iran continues to comply with intrusive agency inspection and verification practices. If Iran increases uranium enrichment at Fordow or begins enrichment to levels greater than 4.5 percent, inspectors will quickly detect the deviations.

Enrichment at Fordow contributes to Iran’s growing stockpile of low-enriched uranium and the slowly decreasing window of time it would take for Iran to produce enough fissile material for one nuclear bomb. But similar to the earlier steps, it is quickly reversible.

While the increased enrichment capacity at Fordow does not pose a near-term risk, the international community considers the Fordow facility to pose a greater proliferation risk than Natanz because Fordow is nestled deep within a mountainous range and its location renders it relatively invulnerable to a military strike. While military action would only set Iran’s program back several years and would likely encourage Tehran to openly pursue nuclear weapons, U.S. presidents have repeatedly stated that the military option is on the table to prevent a nuclear-armed Iran.

While Iran has stated its intention to continue isotope production at Fordow, it is unclear if that work will go forward. After the breach, the U.S. Treasury terminated a sanctions waiver that allowed Rosatom to work with Iran on the Fordow facility conversion. On Dec. 9, Rosatom formally suspended nuclear cooperation with Iran, citing technical issues impeding collocated stable isotope production and uranium enrichment.

5) Abandoning Operational Restrictions

Iran announced Jan. 5 that its nuclear program will no longer be subject to “any operational restrictions” put in place by the JCPOA and that going forward Iran’s activities will be based on its “technical needs.” Zarif, however, specified that Iran will continue to fully cooperate with the IAEA, indicating that Tehran intends to abide by the additional monitoring and verification requirements put in place by the JCPOA. Zarif also said that, like the prior four breaches, the Jan. 5 measures are reversible if its demands on sanctions relief are met.

The extent to which this fifth violation increases the proliferation risk posed by the Iran’s nuclear program depends on how Iran operationalizes the announcement. Unlike prior breaches, Tehran did not provide specific details as to what steps it planned to take that would violate JCPOA limits. The Jan. 5 statement referenced the cap on operating centrifuges as the “last key component” of the nuclear deal’s restrictions that Iran was adhering to, suggesting that Tehran will breach the limit on installed IR-1 machines enriching uranium.

Under the JCPOA, Iran’s uranium enrichment is limited to 5,060 first generation IR-1 centrifuges at the Natanz facility (Section A, para. 1-7). The nuclear deal also permitted Iran to keep 1,044 IR-1 centrifuges at Fordow for isotope research and production. The IAEA confirmed in November that Tehran was still abiding by these limits on installed IR-1 centrifuges (as noted above Iran is enriching uranium at Fordow using some of the machines at that site in violation of the 15 year prohibition set by the deal, but the IAEA has not reported that Iran installed any machines in excess of the permitted 1,044 IR-1s).

Prior to the JCPOA, Iran had installed about 18,000 IR-1 centrifuges, of which about 10,200 were enriching uranium, and about 1,000 advanced IR-2 centrifuges, none of which were operational. Fordow housed about 2,700 of the IR-1 machines, of which 700 were enriching uranium. The remaining machines, including the IR-2s, were installed at Natanz. The JCPOA required Iran to dismantle excess machines and store them at Natanz under IAEA monitoring.

Iran’s statement that its nuclear program will now be guided by “technical needs” provides little insight into how many additional centrifuges Tehran may choose to install and operate in violation of the JCPOA’s limits, or if Iran will take other steps to further violate restrictions breached in 2019. Iran has no need for enriched uranium at this time; its nuclear power reactor at Bushehr is fueled by Russia and the JCPOA ensures that Iran will have access to 20 percent enriched uranium fuel for its research reactor. The Trump administration has continued to waive sanctions allowing the transfer of reactor fuels.

The ambiguity of Iran’s announcement gives Tehran considerable flexibility in calibrating its response. Slowly installing and bringing online additional IR-1 centrifuges to produce uranium enriched to less than five percent would keep Iran on its current trajectory of transparently chipping away at the 12 month breakout established by the JCPOA. This action would also be quickly reversible as Tehran could shut down excess machines in a relatively short time and then dismantle them to return to compliance with the agreement.

If Iran wants to ratchet up pressure more quickly, Tehran could further increase its enrichment level beyond 4.5 percent uranium-235, or more rapidly accumulate a large amount of low-enriched uranium. These steps would decrease more rapidly the window of time it would take for Iran to produce the fissile material necessary for a nuclear weapon and increase the proliferation threat.

The E3’s Decision to Trigger the Dispute Resolution Mechanism

The remaining parties to the JCPOA (China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom and the EU) responded to Iran’s first four violations by condemning Tehran’s actions, but continuing to express support for the JCPOA. After the fifth violation, however, the E3 triggered the dispute resolution mechanism laid out in the JCPOA to address issues of noncompliance.

According to the process laid out in the JCPOA,

- The Joint Commission, which is set up by the JCPOA to oversee implementation and is comprised of the parties to the deal, will have 15 days to resolve the issue, although that period can be extended by consensus. (It appears that the parties have already agreed to extend the time period, as the dispute resolution mechanism was triggered in January and the Joint Commission is not set to meet until mid-February.)

- If the Joint Commission fails to address the issue, the Ministers of Foreign Affairs from the participating states have 15 days to resolve the issue, although that period can be extended by consensus.

- Instead of, or in parallel to the Ministerial Review, an advisory board can be appointed to provide a non-binding opinion on how to address the allegation of noncompliance. The board will be comprised of three members, one appointed by each side of the dispute and a third independent member. The advisory panel has 15 days to deliver an opinion and the Joint Commission then has five days to consider it.

- If, at the end of the process, the dispute is not resolved, the complaining party can notify the UN Security Council. The Security Council then has 30 days to adopt a resolution to continue lifting the UN sanctions. Failure to pass such a resolution snaps UN sanctions back into place.

The E3 have made clear that their intention is to resolve the dispute and preserve the JCPOA, so it is unlikely that they intend to refer the matter to the Security Council. Referral to the Security Council is almost certain to snapback of UN sanctions, which would collapse the deal.

The E3 calculus could change, however, if Iran reduces compliance with inspections or takes steps that significantly increase the proliferation risk posed by the nuclear program, such as resuming enrichment to 20 percent uranium-235 and stockpiling that material. These actions would increase the proliferation risk posed by Iran’s nuclear program and further negate the security benefits that the deal provides to Europe.

Iran threatened to pull out of the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) if the E3 refer Iran’s breaches of the JCPOA to the Security Council. This step would be a significant escalation that would only isolate Iran and subject the country to international pressure. Even states such as China and Russia, which opposed the E3’s decision to trigger the dispute resolution mechanism and the U.S. pressure campaign, would likely join efforts to pressure Iran back into the NPT.

Implications Going Forward

While any breach of the JCPOA is concerning, Iran’s current nuclear activities do not pose a near-term proliferation risk. Though the window of time it would take for Iran to produce the fissile material necessary to manufacture a nuclear weapon is slowly decreasing, the JCPOA imposes a permanent prohibition on weaponization activities. Tehran also continues to comply with the IAEA’s intrusive monitoring and verification safeguards, including the additional protocol to its safeguards agreement, allowing the agency to ensure with a high degree of confidence that fissile materials are not being diverted for weapons production and giving inspectors access to any site to investigate evidence of illicit activity.

While Iran’s systematic breaches of the JCPOA limitations are serious violations of the agreement, the objectives of the deal itself remain uncompromised. Iran’s nuclear program is, at present, exclusively peaceful, and poses far less of a proliferation risk than it did in 2013 when Tehran’s stockpile of low-enriched uranium gas was more than 7,000 kilograms and it would have taken just 2-3 months for Tehran to produce enough weapons-grade material for a bomb. This gives the remaining parties to the deal time to continue working with Tehran to bring Iran back into compliance with the deal.

However, taken together and placed in the context of Tehran’s mounting dissatisfaction with the P4+1’s failure to offer relief promised under the JCPOA, a growing stockpile of low-enriched uranium, increased output from advanced centrifuges, and additional, fortified, enrichment facilities are cause for concern. Having already breached many of the explicit limitations and restrictions designated by the JCPOA, Iran’s next step to breach the deal in early January will likely compound the severity of its violations and jeopardize the future of the deal.

A collapsed JCPOA would have severe implications for regional stability and international security. Dissolution of the JCPOA would significantly compromise the likelihood of Iran engaging in future nuclear nonproliferation agreements and could also spur other states in the region to match Iran’s nuclear capabilities. Without the deal, the international community could be faced with a similar crisis to that which prompted JCPOA negotiations. It is critical that the remaining parties to the JCPOA continue efforts to deliver on sanctions relief envisioned by the deal and press Iran and the United States to return to compliance with their obligations.—JULIA MASTERSON, research assistant, and KELSEY DAVENPORT, director for nonproliferation policy