Volume 11, Issue 4, February 1, 2019

The Trump administration announced today that effective tomorrow, Feb. 2, the United States will suspend implementation of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, and formally notify other parties to the treaty that it will withdraw in six months if Russia does not return to compliance by eliminating its ground-launched 9M729 missile, which the United States alleges can fly beyond the 500-kilometer range limit set by the treaty.

The Wall Street Journal reports that U.S. intelligence agencies assess that the Russians now have four (up from three) battalions of the offending missile, with a total of just under 100 missiles, including spares. The compliance dispute has festered since 2014 and it has worsened since Russia began deploying the system in the field in 2017.

The 1987 INF Treaty, negotiated and signed by President Ronald Reagan and Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, is one of the most far-reaching and most successful nuclear arms reduction agreements in history.

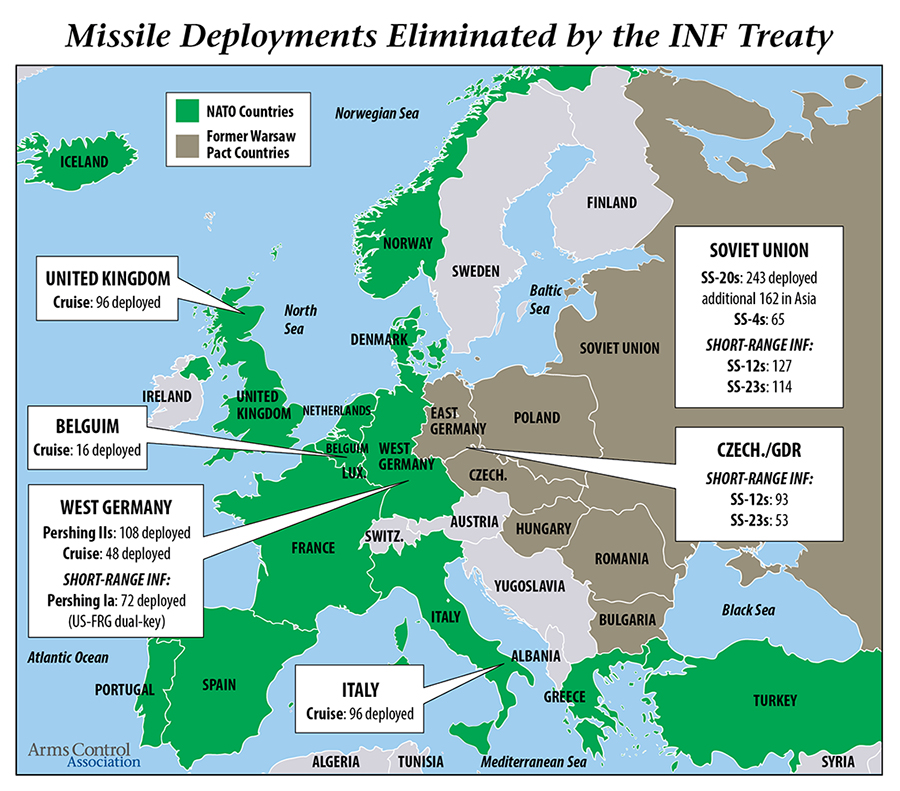

The INF Treaty led to the verifiable elimination of 2,692 Soviet and U.S. missiles based in Europe. The treaty helped bring an end to the Cold War and paved the way for agreements to slash bloated strategic nuclear arsenals and to withdraw thousands of tactical nuclear weapons from forward-deployed areas.

The INF Treaty continues to serve as a check on some of the most destabilizing types of nuclear weapons that the United States and Russia could deploy. Without the treaty, there is a serious risk of a new intermediate-range, ground-based missile arms race in Europe and beyond.

Trump Policy Is Counterproductive and A New Approach Is Needed

Unfortunately, the U.S. threat to terminate the treaty will not bring Russia back into compliance and could unleash a dangerous and costly new missile competition between the United States and Russia in Europe and beyond.

Worse yet, the Trump administration has no viable strategy to prevent Russia from building and fielding more intermediate-range missiles in the absence of the agreement.

Diplomatic options that could bring Russia back into compliance are possible but have not yet been explored. Each side appears to be more interested in winning the blame game than taking the steps necessary to save the treaty.

Any new efforts by the Trump administration to develop or deploy missiles once prohibited by the treaty will be strongly opposed by many NATO members, and the U.S. Congress should withhold funding for procurement of such weapons systems.

This week, 11 U.S. senators reintroduced the "Prevention of Arms Race Act of 2019," which would prohibit funding for the procurement, flight-testing, or deployment of a U.S. ground-launched or ballistic missile – with a range between 500 and 5,500 kilometers – until the Trump Administration provides a report that meets seven specific conditions, including identifying a U.S. ally formally willing to host such a system, and in the case of a European country, have it be the outcome of a NATO-wide decision.

Any new U.S. intermediate-range missile deployments would cost billions of dollars, take years to complete, and are militarily unnecessary to defend NATO allies because existing weapons systems can already hold key Russian targets at risk.

With the INF Treaty’s days numbered, new arms control arrangements are needed to head off a dangerous and costly new missile race in Europe. One option would be for NATO to declare, as a bloc, that no alliance member will field any INF Treaty-prohibited missiles or any equivalent new nuclear capabilities in Europe so long as Russia does not field treaty-prohibited systems that can reach NATO territory.

And if the treaty is terminated, it becomes more important than ever for Washington and Moscow to agree to extend the New START agreement by five years beyond its 2021 scheduled expiration date. Otherwise, there will be no legally-binding limits on the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals for the first time since 1972.

Where Do Efforts to Resolve the Compliance Dispute Stand?

Since President Trump threatened on Oct. 20, 2018 to “terminate” the INF Treaty, there have been two meetings between U.S. Undersecretary of State Andrea Thompson and Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov (in Geneva on Jan. 16 and in Beijing Jan. 31 on the margins of a P5 meeting on disarmament issues). Neither meeting led to progress.

While the recent Russian offer to exhibit the 9M729 is a useful first (and overdue) step in the direction of greater transparency, it has been deemed insufficient by the U.S. side (because it doesn’t allow for independent verification). U.S. officials could propose an alternative that does, but they do not seem to pursue this path because they believe the missile violates the treaty.

Another problem is that the United States is not recognizing the validity of the Russian concerns that U.S. Mk-41 launchers (that are part of the Aegis Ashore missile defense deployment in Romania) could be used to launch offensive missiles. To be clear, Russia is not saying the Mk-41s are an INF violation, they are saying they could be in the future. This is a valid concern and one that could be addressed through site visits or other confidence-building arrangements.

U.S. officials want Russia admit it has violated the treaty (which of course it will not do) and eliminate all of the 9M729s. The U.S. government believes that Russia has, to this point, deployed four battalions of the missiles (probably just under100 total, including spares) with some of those located in Western or Southern Russia, which puts targets in Europe within their estimated range (probably around 1,500-2,000 kilometers). It is not clear whether these missiles are nuclear-armed (probably not), but they are nuclear capable.

Russia claims the 9M729 has a range of 480 kilometers and that they have not conducted any surface-to-surface missile flight tests between 2008 and 2014 that exceeded 500 kilometers. The U.S. Director of National Intelligence says Russia did test the 9M729 from a fixed launcher at a range in excess of 500 kilometers, which means the 9M729 has that capability and is noncompliant.

Diplomatic Options Before August Termination Deadline

Both sides can still pursue diplomatic efforts to resolve the issue. But there is no chance for progress so long as the two sides refuse to adjust their current positions.

The Arms Control Association and our independent, nongovernmental colleagues in the U.S.-Russian-German "Deep Cuts Commission" and others have proposed the following solution that begins with reciprocal verification and inspections of the two systems at issue. This could be negotiated and implemented bilaterally. So far, the United States has rejected this idea, which has been proposed to Trump administration officials by some NATO governments:

- Washington and Moscow should agree to reciprocal site visits by their respective technical experts to examine the missiles or launchers in dispute (the 9M729s and the SM-3/Mk-41s) at their deployment sites. If the 9M729 missile is determined to have a range that exceeds the INF Treaty’s 500-kilometer range limit (which the U.S. experts will likely claim it does) Russia should, as a matter of ‘good faith’ agree to either modify the missile to ensure it no longer violates the treaty or, ideally, halt production and eliminate any such missiles in its possession, including those 9M729s that have been deployed.

- For its part, the United States should agree to modify the Mk-41 missile-defense launchers that Russia believes could be used for offensive purposes, in a way that allows to Russia to clearly distinguish them from launchers that fire offensive missiles from U.S. warships, or agree to other transparency measures to allay Russian suspicions that the launchers contain offensive missiles.

This could be a win-win deal. Such an arrangement would address the concerns of both sides and restore compliance with the treaty without Russia having to acknowledge its original violation of the treaty.

What Missiles Could Each Side Deploy in the Absence of the INF Treaty?

As Kingston Reif reports in Arms Control Today, Russian President Vladimir Putin stated on Dec. 18 that if the United States “breaks the treaty,” Russia will be “forced to take additional measures to strengthen [its] security.” He further warned that Russia could easily conduct research to put air- and sea-launched cruise missile systems “on the ground, if need be.” This could include additional numbers of the 9M729 ground-launched cruise missile on mobile launchers.

For its part, the Trump administration is already seeking to develop new conventionally armed cruise and ballistic missiles to “counter” Russia’s 9M729 missile. The fiscal year 2018 National Defense Authorization Act required “a program of record to develop a conventional road-mobile [ground-launched cruise missile] system with a range of between 500 to 5,500 kilometers,” including research and development activities.

The Defense Department requested, and Congress approved, $48 million in fiscal year 2019 for research and development on and concepts and options for conventional, ground-launched, intermediate-range missile systems in response to Russia’s alleged violation of the INF Treaty.

One option might be a ground-launched variant of the Air Force’s Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile or the Navy’s Tomahawk sea-based cruise missile. Another option could be an intermediate-range ballistic missile could be derived from the U.S. Army’s short-range Army Tactical Missile System, a surface-to-surface missile with a reported range of just under 500 kilometers. The Wall Street Journal reports that U.S. officials say, "It is unlikely that flight tests of these new systems would be conducted before the end of the [the INF Treaty’s] six-month withdrawal period.”

However, key NATO states have already expressed opposition to basing any such systems in Europe. Heiko Maas, Germany’s foreign minister told Spiegel Online Jan. 11, 2019: "Even if we are unable to save the INF Treaty, we cannot allow the result to be a renewed arms race. European security will not be improved by deploying more nuclear-armed, medium-range missiles. I believe that is the wrong answer."

Alternative Risk Reduction Strategies in the Absence of INF

Because the loss of the INF Treaty would open the door to a new Euro-missile race, there are steps that can and must be pursued that would benefit the security interests of Russia, Europe, and the United States, as well as the prospects of future arms controls agreements.

- One option would be for NATO to declare, as a bloc, that no alliance members will field any INF Treaty-prohibited missiles or any equivalent new nuclear capabilities in Europe so long as Russia does not field treaty-prohibited systems that can reach NATO territory. This would require Russia to remove those 9M729 missiles that have been deployed in western Russia. This would also mean forgoing Trump’s plans for a new ground-launched, INF Treaty-prohibited missile. Because the United States and its NATO allies can already deploy air- and sea-launched systems that can threaten key Russian targets, there is no need for such a system. Key allies, including Germany, have already declared their opposition to stationing new intermediate-range missiles in Europe. Key members of Congress have introduced legislation that would block procurement funding for any U.S. system currently banned by the treaty.

- Another possible approach would be to negotiate a new agreement that verifiably prohibits ground-launched, intermediate-range ballistic or cruise missiles armed with nuclear warheads. As a recent United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research study explains, the sophisticated verification procedures and technologies already in place under the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) can be applied with almost no modification to verify the absence of nuclear warheads deployed on shorter-range missiles. Such an approach would require additional declarations and inspections of any ground-launched, INF Treaty-range systems. To be of lasting value, such a framework would require that Moscow and Washington agree to extend New START by five years. New START is now scheduled to expire in 2021 and talks on extension have not yet begun.

- A third variation would be for Russia and NATO to commit reciprocally to each other – ideally including a means of verifying the commitment - that neither will deploy land-based, intermediate-range ballistic missiles, or nuclear-armed cruise missiles (of any range), capable of striking each other’s territory.

There may be still other options that would meet each sides’ security and help to avoid a replay of the 1980s, in which each side had a justifiable fear of sudden nuclear attack.

INF Termination Is Bad. Failure to Extend New START Would Make Things Worse.

If the INF Treaty collapses, as appears likely, the only remaining agreement regulating the world’s two largest nuclear stockpiles will be New START. That 2010 treaty, which limits the two sides’ long-range missiles and bombers and caps the warheads they carry to no more than 1,550 each, is due to expire in 2021 unless Trump and Putin agree to extend it by a period of up to five years, as allowed for in the accord’s Article XIV.

Key Republican and Democratic senators, former U.S. military commanders, and U.S. NATO allies are on record in support of the treaty’s extension, which can be accomplished without further Senate or Duma approval.

Unfortunately, U.S. National Security Adviser John Bolton may try to sabotage that treaty too. Since arriving at the White House in April, he has been slow-rolling an interagency review on whether to extend New START and refusing to take up Putin’s offer to begin extension talks.

Extension talks should begin now, in order to resolve outstanding implementation concerns that could delay the treaty’s extension.

Without New START, there would be no legally binding limits on the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals for the first time since 1972. Both countries would be in violation of their Article VI nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty obligation to “pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament....”

Bottom Line

The INF Treaty crisis is a global security problem. Without serious talks and new proposals from Washington and Moscow, other nations will need to step forward with creative and pragmatic solutions that create the conditions necessary to ensure that the world’s two largest nuclear actors meet their legal obligations to end the arms race and reduce nuclear threats.—DARYL G. KIMBALL, Executive Director