A Nonproliferation Success That Should Not Be Squandered

Volume 10, Issue 1, January 9, 2018

The Trump administration is approaching two deadlines this week that are tied to the nuclear deal between the P5+1 (China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States) and Iran: the president’s quarterly certification to Congress and the renewal of sanctions waivers, which are required for continued U.S. compliance with the nuclear deal known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).

U.S. President Donald Trump is expected to withhold the 90-day certification to Congress, which includes an assessment of Iran’s compliance with the accord and an assessment on whether or not the deal remains in U.S. national security interests. Trump withheld the last certification in October, despite Iran’s compliance with accord, using the subjective determination that the sanctions relief Iran received is disproportionate to the nuclear restrictions. Since the certification is a U.S. legal requirement under the Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act, withholding it does not violate the JCPOA. Given that the international community has become immune to Trump’s bellicose rhetoric surrounding the value of the deal, unless Trump alleges an Iranian violation, withholding certification is likely to become part of the status quo if the United States stays in the deal.

However, Trump has not yet indicated his decision on a second Iran deal deadline: the renewal of U.S. sanctions waivers, which is more critical for the future of the multilateral accord. The United States will violate its commitment to lift certain sanctions under the deal if Trump fails to issue the waivers between Jan. 12-17.

Reimposition by the United States of nuclear-related sanctions would not only violate Washington’s commitments under the deal, but also risks drying up the economic benefits that were promised to Iran in exchange for accepting stringent limits and monitoring on its nuclear program. Because the U.S. sanctions include extraterritorial measures, reimposition of these sanctions would affect companies outside of the United States that have resumed legal business with Iran permitted under the nuclear deal. As a result, it would be more difficult for the government of Iranian president Hassan Rouhani to continue abiding by the terms of the deal if economic benefits evaporate. If Iran abandons the JCPOA in response to a U.S. violation, the threat posed by Iran’s nuclear program could re-emerge and spark further instability in the region.

A Legislative Fix?

Trump has given little indication as to how he will approach the upcoming deadlines, but Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said in a Jan. 5 interview with AP that the president will either “fix [the deal] or cancel it.”

There is no legitimate reason for the United States to unilaterally try to “cancel” the deal. Iran remains in compliance with the nuclear restrictions under the JCPOA—a fact affirmed by the most recent quarterly report of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in November and by Washington’s P5+1 partners.

The threshold for what Trump would need to see as a “fix” in order to stay in the deal, however, remains vague.

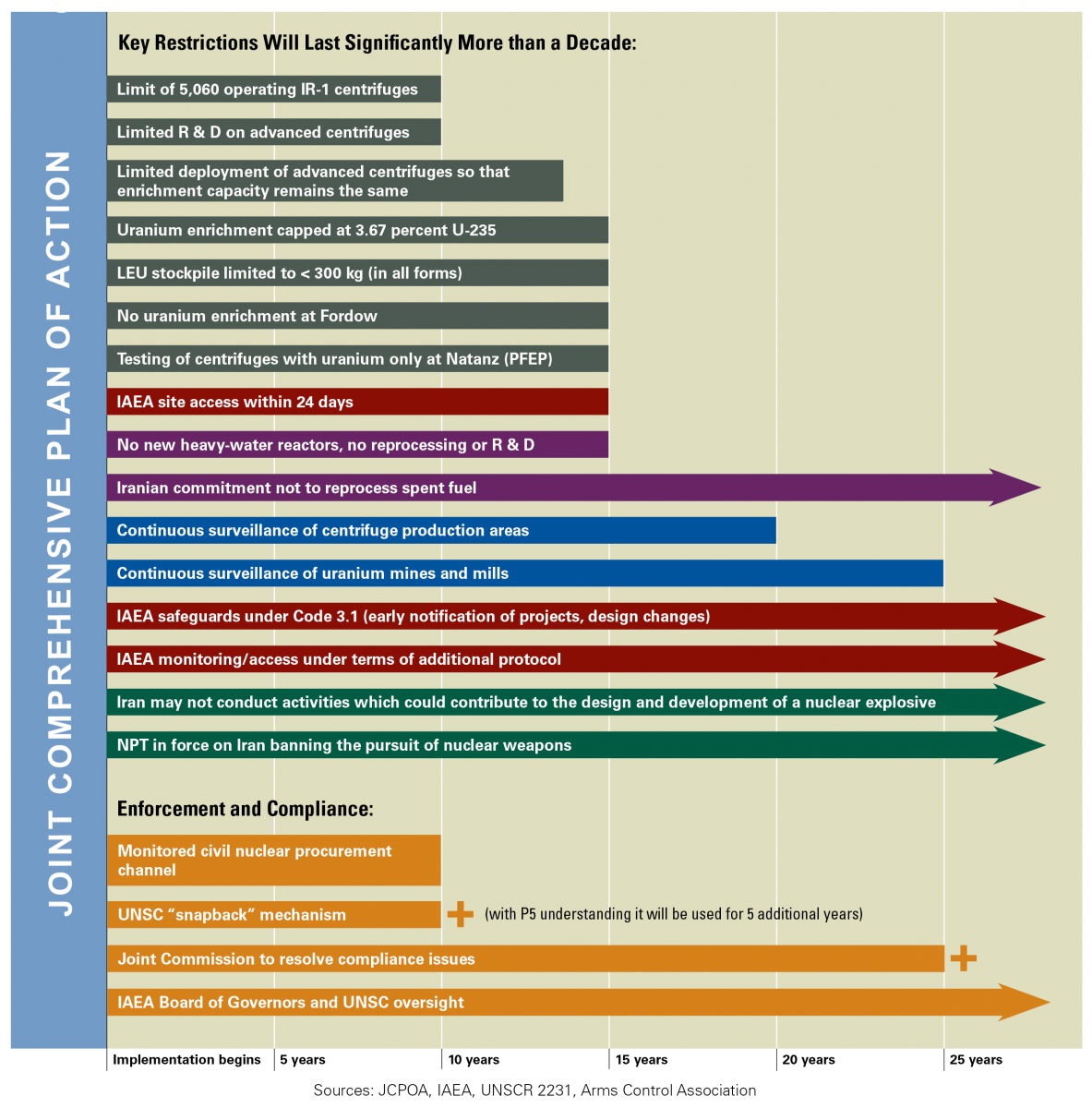

In October, Trump directed his administration to work with Congress to develop legislation that would address what he viewed as flaws in the agreement, including the so-called "sunset" provisions, or nuclear restrictions that phase out over time, and ballistic missile activity, which is not covered by the deal but is dealt with in a UN Security Council resolution endorsing the agreement. In October, Trump said he would exit the deal if these concerns are not resolved, but did not set a deadline for results or a threshold for what would satisfy his concerns.

As a result, it remains unclear if efforts such as the commitment from Germany, France and the United Kingdom to work with the United States on addressing Iran’s ballistic missile program separate from the nuclear deal are enough to keep the United States in compliance with the terms of the multilateral JCPOA agreement.

Tillerson also said that the administration is pursuing a fix with members of Congress on a “very active basis” and implied that a fix did not have to be finalized, but just in the works, for Trump to reissue the waivers. U.S. Senators Bob Corker (R-Tenn.) and Ben Cardin (D-Md.), met with U.S. National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster Jan. 4 to discuss Iran, but did not provide any details on possible legislation.

While such legislation might appease Trump’s political desire to distance himself from an agreement negotiated during the Obama tenure, it is critical that any congressional initiative on the issue does not violate or seek to recast the terms of the JCPOA.

For example, unilateral efforts by the U.S. Congress to indefinitely extend all or some of the JCPOA’s core nuclear restrictions on Iran, which are due to phase out over time, as Senators Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) and Corker (R-Tenn.) proposed in October, would violate the accord and are strongly opposed by Washington’s negotiating partners.

Appeasing Trump’s demand to "fix" the agreement also risks setting a dangerous precedent—that threating to abandon the deal can extract additional concessions. There is no guarantee that Trump—or another leader—will not change the goal posts again down the road and demand more "fixes" in order for the United States to continue complying with the accord.

On the other hand, Congress could eliminate provisions requiring the president to issue the certification every 90 days, which might appeal to Trump as he would no longer have to publically acknowledge the deal on a regular basis. Such a move would only impact U.S. law and have no bearing on the deal itself.

Moving the spotlight off the Iran deal every 90-days might also give the United States and its negotiating partners more time to work multilaterally on options to build upon the nuclear deal and restore confidence in the U.S. commitment to the agreement.

The Nonproliferation Consequences of Nixing the Deal

It is unclear what steps Iran will take if the United States violates the accord, but if Tehran no longer sees benefit to remaining in the deal and resumes nuclear activities that are now restricted or halts cooperation on verification measures mandated under the JCPOA, there could be significant nonproliferation consequences.

Bahram Qassami, spokesman for the Iranian Foreign Ministry said Jan. 8 that “all options are on the Islamic Republic’s table” and they will be quickly implemented in response to any U.S. actions. Ali Akbar Salehi, head of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, said in November that Iran could resume enrichment to 20 percent within days if the United States walks away from the deal. Before the negotiation of a November 2013 interim nuclear deal with the P5+1, Iran enriched uranium to the 20-percent uranium-235 level, which is below the level necessary for nuclear weapons but more of a threat than the current 3.67 percent uranium-235 limit set by the JCPOA.

Resumption of higher-level enrichment and/or the operation of additional centrifuges, including advanced machines, that were dismantled as part of the JCPOA, could return Iran to the 2-3 month “breakout time” (the time estimated to produce enough fissile material for one nuclear weapon) that it was before the deal was negotiated. As a result of the restrictions and limits under the deal, the breakout time is currently estimated to be around 12 months.

Tehran could also choose to stop implementing the additional protocol to its IAEA safeguards agreement, which it currently adheres to voluntarily under the deal. Salehi hinted at this Jan. 8 when he stated that Iran would adopt measures that could affect the current level of cooperation with IAEA. Losing the additional protocol would give inspectors less access to Iranian nuclear facilities and information about its program.

In addition to an increased risk posed by an unrestricted Iranian nuclear program, there are regional implications to losing the nuclear deal.

Currently, Saudi Arabia is developing a nuclear energy program and pursuing a nuclear cooperation agreement with the United States. Thus far, Saudi Arabia has refused to forswear acquisition of uranium enrichment and reprocessing capabilities. If the nuclear deal with Iran collapses, and Iran’s uranium enrichment program is unrestricted, it is more likely that Saudi Arabia will also choose to go down this route.

For decades, the United States has placed a high premium on halting the further spread of enrichment and reprocessing technology. It would be a mistake for the U.S. executive branch or legislative branch to take actions that jeopardize continued implementation and compliance with Iran deal in a way that risks the pursuit of these sensitive technologies by other states in the troubled Middle East region.

Responding to the U.S. Decision

If Trump abandons the nuclear deal, it behooves Iran and the remaining P5+1 partners to use what tools they have to continue implementing the deal.

The European Union, for instance, could issue a blocking regulation to try and protect European companies and businesses from extraterritorial sanctions. The EU has used this regulation in the past when the United States imposed secondary sanctions on Cuba that the EU did not support.

An EU sanctions blocking regulation, however, cannot guarantee protection and as a result the risk of secondary sanctions might cause companies and investors to pull out of the Iranian market. Nevertheless, it would send a powerful message to the United States that the EU rejects Trump’s irresponsible behavior and continues to support the deal. Issuing the block regulation would also help demonstrate to the Trump administration that the United States will only be further isolated if it continues to reject its international obligations.

While political pressures in Iran might prevent continued implementation of the deal in the long run, the Rouhani government should do what it can to continue meeting the limits of the JCPOA. The current program allowed under the nuclear deal is consistent with Iran’s needs and a commitment by the rest of the P5+1 to continue to take steps, such as providing 20-percent enriched fuel for the Tehran Research Reactor, would meet needs not covered by Iran’s domestic nuclear activities.

Without question, the nuclear deal with Iran has effectively removed the existential threat of an Iranian nuclear weapons program and significantly scaled back the country’s nuclear activities. The Trump administration would be foolish to disrupt a successful deal that has addressed a significant threat in a tension-filled region and contributes to strengthening the global nonproliferation regime.

If, in the end, Trump take steps to kill or undermine the successful Iran nuclear deal, the international community—particularly the remaining P5+1 and Iran—should do what they can to continue to implement it. The last thing the Middle East and the United States needs at this time is a major nuclear proliferation crisis manufactured by the White House.—KELSEY DAVENPORT, director for nonproliferation policy