Volume 8, Issue 1, April 15, 2016

The Nuclear Security Summit process and associated U.S. nuclear threat reduction programs have played a vital role in reducing the risk of a nuclear or radiological attack by terrorists. But the threat is constantly changing and may have grown in recent years in light of the rise of the Islamic State group and indications it may have nuclear and/or radiological ambitions.

Despite noteworthy achievements, however, significant work remains to be done to prevent terrorists from detonating a nuclear explosive device or dirty bomb. For example, even after four Nuclear Security Summits there are no comprehensive, legally-binding international standards or rules for the security of all nuclear materials. The existing global nuclear security architecture needs to continue to evolve to become more comprehensive, open, rigorous, sustainable, and involve the further reduction of material stockpiles.

It is thus puzzling that just weeks before the final summit in Washington earlier this month, the Obama administration submitted to Congress a budget that proposed significant spending reductions for key National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) programs that lessen nuclear security and nonproliferation risks, accelerating a trend in recent years of short-sighted cuts to these programs. If implemented, these decreases will slow progress on key nuclear security initiatives, jeopardize the sustainability of those initiatives, and undermine U.S. leadership in this area.

As the Senate and House of Representatives begin their work on the fiscal year 2017 defense authorization and energy and water appropriations bills—which establish spending levels and set policy for Defense Department and NNSA activities—lawmakers should reverse these ill-advised budget cuts. Additionally, Congress should encourage the NNSA to augment its nuclear and radiological security work to help ensure the end of the summit process does not weaken progress toward continuously improving global nuclear and radiological material security.

Disappointing Budget Request

If the risk of nuclear or radiological terrorism isn’t on your mind, it should be. The recent Islamic State group-perpetrated terrorist attacks in Brussels offered another bloody reminder of the danger of terrorism. To make matters worse, reports indicate that two of the suicide bombers who perpetrated the attack had also carried out surveillance of a Belgian official with access to a facility with weapons-grade uranium and radioactive material.

A new report published on March 21 by the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs concludes that the risk of nuclear terrorism may be higher than it was at the time of the third Nuclear Security Summit in 2014 due to the slowing of nuclear security progress and the rise of the Islamic State group.

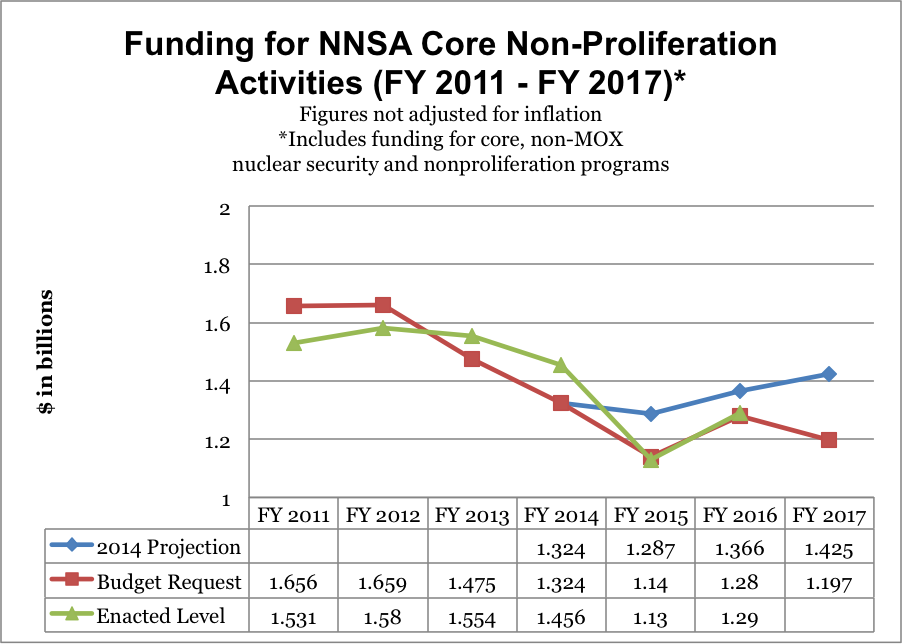

Against this concerning backdrop, the NNSA, a semiautonomous agency of the Energy Department responsible for the bulk of U.S. nuclear security work, in February requested $1.47 billion for core nuclear security, nonproliferation, and counterterrorism programs in fiscal year 2017—a reduction of $62.4 million, or 3.8 percent, relative to the current fiscal year 2016 level. (Note: these figures exclude the administration’s request of $270 million to terminate the Mixed Oxide (MOX) fuel program for excess U.S. weapons plutonium disposition.)

The drop is even steeper when measured against what the NNSA projected it would request for these programs in its fiscal year 2016 submission, which was issued in February 2015. The agency had said it planned to ask for $1.65 billion in fiscal year 2017, or roughly $185 million more than the actual proposal.

The largest proposed reduction in the request is to the Global Material Security program, which improves the security of nuclear materials around the world, secures orphaned or disused radiological sources—which could be used to make a dirty bomb—and strengthens nuclear smuggling detection and deterrence. Within this program, the NNSA is seeking $7.6 million less than last year’s appropriation for radiological material security programs and roughly $270 million less for these activities over the next four years than it planned to request over the same period, last year.

Most experts agree that the probability of a terrorist exploding a dirty bomb is much higher than that of a nuclear device. This is due in large part to the ubiquitous presence of these materials, which are used for peaceful applications like cancer treatment, in thousands of locations and in almost every country around the world, many of which are poorly protected and vulnerable to theft. A new report published last month by the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI) noted that only 14% of International Atomic Energy Agency member states have agreed to secure their highest risk radiological sources by a specific date.

Along with reducing the budget for radiological security, the NNSA is planning to transition from a primarily protect-based approach for radiological materials to one that emphasizes permanent threat reduction through the removal of sources and the promotion of alternative technologies, when feasible. While it makes sense to seek to replace these sources as opposed to securing them in perpetuity, this revised approach raises numerous questions, including whether some sources will remain vulnerable for longer than under the previous strategy. At the current planned pace, it would take another 17 years to meet the NNSA’s much-reduced target of helping to secure just under 4,400 buildings around the world with dangerous radioactive material—down from a target of roughly twice that just last year.

Elsewhere in the NNSA nonproliferation budget, funding for Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation Research and Development activities would fall to $394 million from its $419 million fiscal year 2016 appropriation. This program matures technologies used in tracking foreign nuclear weapons programs, illicit diversion of nuclear materials, and nuclear detonations. The NNSA projected a request of $430 million in fiscal year 2017 research and development funding in its fiscal year 2016 request.

The NNSA has defended some of the reductions to the nonproliferation account on the grounds that several major projects have been completed, thereby lessening resource needs, and that the impact of spending cuts can be mitigated by using unspent money left over from prior years, largely due to the suspension in late 2014 of nearly all nuclear security cooperation with Russia. But the cuts proposed for fiscal year 2017, relative to what was projected last year, are significant, especially to the radiological security and research and development programs where the NNSA does not say they will use unspent balances.

An Energy Department task force report on NNSA nonproliferation programs released last year expressed concern about the recent trend of falling budgets for those programs (see chart). “The need to counter current and likely future challenges to nonproliferation justifies increased, rather than reduced, investment in this area,” the report said.

Similarly, Andrew Bieniawski, a former deputy assistant secretary of Energy who ran the NNSA’s Global Threat Reduction Initiative during both the George W. Bush and Obama administrations and who is now a vice president at NTI, said last month that the agency’s recent budget requests “do not match the growing threat and they certainly don’t match the fact that you are having a presidential nuclear security summit.”

Many members of Congress agree with these concerns. In August 2014, 26 senators sent a letter to the Office of Management and Budget seeking increased funding for NNSA nuclear nonproliferation programs for fiscal year 2016. Though the 2016 request was higher than the previous year’s enacted level, it did not meet the Senators’ desire “to further accelerate the pace at which nuclear and radiological materials are secured and permanently disposed.”

Reinvigorating Congressional Leadership

The global effort to prevent nuclear terrorism is at a key inflection point. While the United States can’t tackle the challenge on its own, U.S. leadership and resources are essential. The Obama administration’s fiscal year 2017 budget request was a missed opportunity to advance many good ideas in this space that haven't received adequate attention and investment.

Congress has a critical role to play in this endeavor, and there are a number of steps it can take this year to sustain and strengthen U.S. and global nuclear and radiological security efforts.

First, Congress should increase fiscal year 2017 funding for NNSA radiological security and nonproliferation research and development efforts, the two programs hardest hit by the agency’s proposed budget cuts. Additional funding would allow an acceleration of efforts to secure dangerous radiological materials and ensure the United States is prepared to confront emerging security and nonproliferation challenges.

Congress should also call for a global strategy, stronger regulations, and increased funding to secure and eliminate the most vulnerable highest-risk radiological sources around the world during the first term of the next administration. This multidimensional effort should entail a number of elements, including: securing the most vulnerable sources (where needed); requiring the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission to implement stronger regulatory requirements; supporting universal adherence to the IAEA Code of Conduct on radiological sources; mandating additional cost-sharing by industry; and, where appropriate, accelerating the development and use of alternative technologies. An accelerated international radiological security effort would be consistent with a proposal from Sen. Carper (D-Del.) requiring the administration to craft a plan for securing all high-risk low-level radiological material in the United States.

In addition, Congress should require NNSA to report on its research and development activities and identify opportunities to expand them in areas such as:

- developing alternatives to high performance research reactors that run on highly enriched uranium (HEU);

- converting HEU-powered naval reactors to use low enriched uranium (LEU) fuel (the White House announced on March 31 that the Energy Department is forming a research and development plan for an advanced fuel system that could enable use of LEU in naval reactors); and

- examining ways adversaries could potentially use 3D printing and other new technologies to make nuclear-weapons usable components.

Other ideas that have been put forth to augment NNSA’s (and the rest of the interagency) nuclear security and nonproliferation work worthy of Congressional backing include:

- completing a prioritization of nuclear materials at foreign locations for return or disposition, to identify the most vulnerable material stocks to focus efforts on, and establishing a time frame for doing so;

- developing new detection and monitoring technologies and approaches to verify future nuclear arms reductions;

- outlining a plan for how to expand U.S. nuclear security cooperation with China, India, and Pakistan and addressing obstacles to such an expansion and how they could be overcome;

- developing approaches to rebuild nuclear security cooperation with Russia that would put both countries in equal roles;

- building a global nuclear materials security system of effective nuclear security norms, standards, and best practices worldwide;

- enhancing protections against nuclear sabotage; and

- strengthening—and sharing—intelligence on nuclear and radiological terrorism threats.

In addition, Congress should seek ways to dissuade other states from pursuing programs to reprocess fuel from nuclear power plants, which lead to the separation of plutonium.

While the Nuclear Security Summit process has seen significant progress in the minimization of highly enriched uranium (HEU) for civilian purposes, global civilian plutonium stockpiles continue to grow. East Asia in particular is on the verge of a major build up of separated plutonium, which could be used in nuclear weapons and poses significant security risks. Japan and China both have plans to reprocess on a large-scale, and doing so would almost certainly prompt South Korea to follow suit.

To its credit, the Obama administration has recently been more vocal in expressing its concerns about these plans. Congress should encourage the administration, and NNSA in particular, to engage in additional cooperative work with countries in East Asia on spent fuel storage options and the elimination of excess plutonium stockpiles without reprocessing.

Over the years, U.S. support for nuclear security programs at home and abroad has resulted in an enormously effective return on investment that greatly strengthens U.S. security, and will be even more important in the years ahead in absence of head of state level summit meetings.

Indeed, there is a long legacy of members of Congress from both parties working together to reduce nuclear risks. For example, in 1991, Senators Sam Nunn (D-Ga.) and Richard Lugar (R-Ind.) put forward the “Soviet Nuclear Threat Reduction Act of 1991,” which authorized $400 million to create U.S.-led programs assist the countries of the former Soviet Union secure and eliminate nuclear weapons, chemical weapons, and other weapons. This effort became known as the Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) Program, which has successfully liquidated thousands of Cold War-era Soviet weapons.

Twenty-five years later, the evolution of security and proliferation challenges requires similarly bold and innovative Congressional leadership.

—KINGSTON REIF, director for disarmament and threat reduction policy

###

The Arms Control Association is an independent, membership-based organization dedicated to providing authoritative information and practical policy solutions to address the dangers posed by the world's most dangerous weapons.