"In my home there are few publications that we actually get hard copies of, but [Arms Control Today] is one and it's the only one my husband and I fight over who gets to read it first."

Using Multilateralism to Fill the Space Policy Vacuum

November 2023

By Il-hoon Kim

The first series of meetings of the UN open-ended working group on reducing space threats through norms of responsible behaviors and actions came to a close on September 1 with two agreements: that there was no agreement and that a compromise is beyond the horizon.

In fact, not even the title of a procedural report could be agreed. Arguably, this stems from a fundamental difference of philosophy on how space security should be governed internationally. Despite the overwhelming support for the report among states and civil society representatives in the working group, a handful of states abused the working group’s consensus rule and blocked the report. These states maintained a single-minded position that only legally binding instruments are meaningful. They refused to accept that the novel approach of cultivating a set of responsible behaviors to address the threats in, to, and from outer space enjoys wide backing from the international community, as evidenced by the fact that UN General Assembly Resolution 76/231, which established the working group, was adopted on a vote of 150-8.1

In fact, not even the title of a procedural report could be agreed. Arguably, this stems from a fundamental difference of philosophy on how space security should be governed internationally. Despite the overwhelming support for the report among states and civil society representatives in the working group, a handful of states abused the working group’s consensus rule and blocked the report. These states maintained a single-minded position that only legally binding instruments are meaningful. They refused to accept that the novel approach of cultivating a set of responsible behaviors to address the threats in, to, and from outer space enjoys wide backing from the international community, as evidenced by the fact that UN General Assembly Resolution 76/231, which established the working group, was adopted on a vote of 150-8.1

Four rounds of the working group were organized to implement the mandate of the UN resolution. It called for taking stock of the existing international legal and other normative frameworks concerning threats arising from state actions with respect to outer space and considering current and future threats by states to space systems and actions, activities, and omissions that could be considered irresponsible. In addition, the working group was charged with recommending to the General Assembly possible norms, rules, and principles of responsible behaviors relating to threats by states to space systems, including how such recommendations might contribute to the negotiation of legally binding instruments and prevent an arms race in outer space.

Except for a handful of states that opposed the working group from its inception, the majority of delegations involved in the deliberations over the last two years expressed support for this open, inclusive, and substantive platform and its mission to forge a consensus on concrete ways to enhance space security with the participation of all stakeholders.2 In a joint statement made at the closing session of the working group, 39 participating states reaffirmed that “political commitments on responsible behaviors can be developed in support of, and without prejudice to, the pursuit of legally binding measures and instruments in this area” and insisted that “these two approaches are not mutually exclusive.” They also appreciated the working group as “an excellent starting point that complements others’ efforts related to enhancing outer space security,” including the newly established group of governmental experts on the prevention of an arms race in outer space.

Notwithstanding, states that opposed the General Assembly resolution clearly showed that they would not allow consensus. Their key arguments against a behavior-based approach included that only a legally binding instrument can guarantee security in outer space; that the term “responsible behavior” is too subjective, vague, and unclear; and that capabilities, not behaviors, should be the basis of discussion. In short, these states asserted that the negotiation of the draft Treaty on the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space and of the Threat or Use of Force Against Outer Space Objects is the only viable way forward.

As plausible as they may sound, these arguments are faulty. First, the blind pursuit of legally binding instruments alone cannot ensure binding solutions. The war in Ukraine, intensified by Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, is a clear example. What good is a law that is not respected and that cannot be enforced effectively? The world need not be reminded that North Korea promised never to produce or acquire a nuclear weapon when it joined the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1985 at the urging of the Soviet Union, which provided Pyongyang with nuclear research reactors. Nevertheless, North Korea developed its nuclear programs, announced its withdrawal from the NPT in 2003, has advanced its nuclear weapons program, and conducted six nuclear tests in the 21st century. There are countless examples of states violating their legal commitments.

The subjective nature of "responsible behaviors” also should not be a barrier to exploring proposals with which nations can agree. There is no disagreement that international law and norms should be based on objectivity. Yet, the international community also must not chase rainbows, believing that there is such a thing as an absolute good or objectivity in international affairs. Many if not most existing international laws and norms result from iterative processes. The act of war itself was not prohibited and was not even regarded as an irresponsible act before the difficult lessons learned through World War II were translated into the UN Charter. In other words, the working group and other consensus-seeking efforts provide valuable platforms by which to exchange views, shape converging ideas, and collectively confer objectivity on the norms that states can agree to follow. In addition, the objectivity of law, whether domestic or international, must undergo subjective perception and interpretation by those who implement and enforce it. Laws themselves are not static either.

Finally, the nature of space—the speed at which events occur and the dual-purpose characteristics of space systems—make capability-based prohibitions and their verification extremely difficult if not impossible at this stage of technological development. To date, weapons of mass destruction are the only type of weapons that are prohibited under existing international law (the 1967 Outer Space Treaty) from being stationed in orbit around the Earth or other celestial bodies.3 The sole purpose of the weapons of mass destruction is quite clear: to inflict mass destruction. There is no peaceful or commercial application, so it is easier to impose a legal ban. On the other hand, commercial or civilian satellites can be used beyond their original purpose, for example, as bullets that can apply kinetic force against other space systems. Robot arms on one satellite can be used to put other satellites off orbit or destroy them altogether. Governance of space security must take into consideration all of these critical and realistic characteristics as a legal ban could unduly restrict peaceful uses.

Finally, the nature of space—the speed at which events occur and the dual-purpose characteristics of space systems—make capability-based prohibitions and their verification extremely difficult if not impossible at this stage of technological development. To date, weapons of mass destruction are the only type of weapons that are prohibited under existing international law (the 1967 Outer Space Treaty) from being stationed in orbit around the Earth or other celestial bodies.3 The sole purpose of the weapons of mass destruction is quite clear: to inflict mass destruction. There is no peaceful or commercial application, so it is easier to impose a legal ban. On the other hand, commercial or civilian satellites can be used beyond their original purpose, for example, as bullets that can apply kinetic force against other space systems. Robot arms on one satellite can be used to put other satellites off orbit or destroy them altogether. Governance of space security must take into consideration all of these critical and realistic characteristics as a legal ban could unduly restrict peaceful uses.

This is why the idea of norms, rules, and principles of responsible behaviors to address space threats was proposed to the international community by a number of states. Security threats involve action or inaction by a state that is deliberate, but the nature of space makes it impossible to verify that deliberateness or intent. As a result, many countries, including South Korea, have been ardent supporters of addressing space security threats through observable behaviors rather than prohibiting dual-use capabilities. Such prohibitions inevitably will have restrictive effects on the legitimate development and use of space. Banning robot arms, for instance, would mean that this capability cannot be used even for peaceful purposes, such as repairing satellites or rescuing satellites in distress.

This concern about deliberate threats also differentiates the space security norms now under discussion by the working group from the existing space safety governance mechanism led by UN Committee on Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. The UN committee was established by the General Assembly in 1959 to review international cooperation on the peaceful uses of outer space, study space-related activities that could be undertaken by the United Nations, encourage space research programs, and study legal problems arising from outer space exploration. Opponents of the behavior-based approach have been critical of the fact that safety issues must remain under the UN committee purview and that duplicity must be avoided. Risks or hazards, meaning consequences not caused by deliberate actions that potentially arise from peaceful space development activities, should continue to be regulated by existing international legal instruments, including the five outer space treaties and frameworks such as the UN committee.4 Issues pertaining strictly to space traffic management and other matters that are covered under guidelines adopted by the UN committee in June 2018 would fall under this category.5

Although duplication undoubtedly should be avoided as much as possible, the difference in the membership between the respective mechanisms and the importance of security issues must be given due consideration. For instance, only 102 states are members of the UN committee. Space security will have ramifications for the wider world, not just for space-faring nations, considering the growing global dependence on services provided by various space systems. For instance, a country could decide to destroy its own satellites, but the resultant debris likely will endanger the space systems of other states. The debris also could have a prohibitive effect on areas of space that otherwise could have been utilized for peaceful purposes if not now occupied by long-lived debris. Such problems caused by debris creation may fall under the purview of the UN committee, but the actions that caused the problem have a security origin and therefore cannot be addressed fully by confining the discussions to the handling of the aftermath of such events.

Closing the vacuum of norms is expected to bring realistic, tangible benefits to humanity as a whole. Among the benefits identified in the draft report of the chair of the working group are reducing threats to international peace and security related to activities in outer space, contributing to negotiations on a legally binding treaty or other instrument to prevent an arms race and war in outer space, and contributing to the long-term sustainability of outer space activities and the continuing and nondiscriminatory use and exploration of outer space.

In addition, the draft report cited the benefits of reducing the risk of misunderstandings, misperceptions, miscalculations, and unintended escalation and conflict; encouraging transparency and communication regarding space activities to avoid misinterpretation; and ensuring that private actors are accountable for their actions in outer space and fostering cooperation between states and private actors in the protection of space systems. Other benefits included encouraging the development and deployment of new technology consistent with international law.6

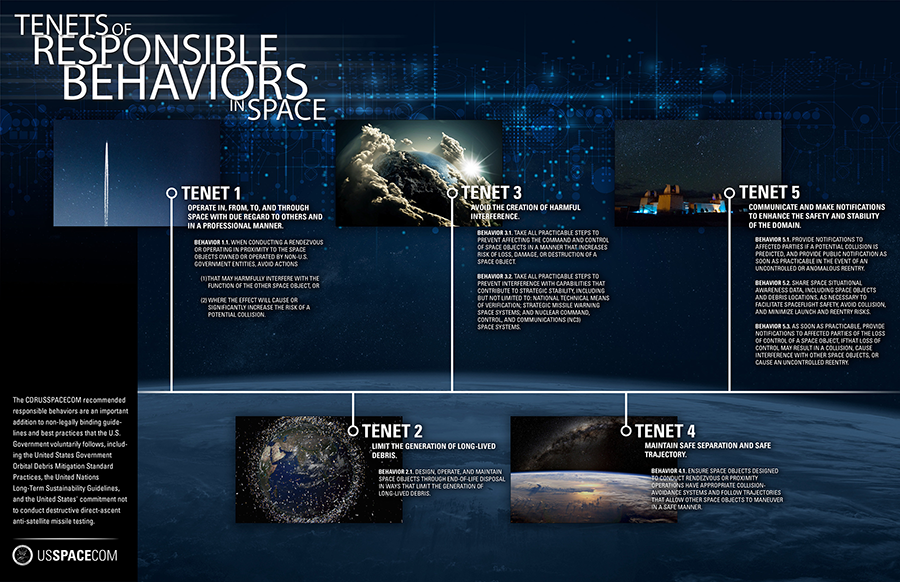

The rapid pace of technological advances and the advent of the new space era has made outer space increasingly congested, contested, and competitive. Many states and much of the world’s population are reliant on services provided by space systems. As a result, it would be detrimental and perilous to leave outer space void of any norms to govern the security dimensions. Threats emanate in all four vectors: earth to space, space to space, space to earth, and earth to earth. Threatening activities include launching space vehicles without coordinating beforehand with potentially affected countries; conducting rendezvous and proximity operations without prior notification, coordination, or consent; and testing or using destructive direct-ascent anti-missiles. Other potential threats include deliberately interfering with the command and control of space systems or impairing the ability of an operator to control a satellite and jamming or spoofing the signals of positioning, navigation, and timing satellites or interfering with such systems via cyberspace or other means.

A majority of UN member states aspire to create legally binding instruments to this end. Yet as reflected in the chair’s draft report, many working group participants “reaffirmed that possible solutions to outer space security can involve a combination of legally binding obligations and non-legally binding measures, and that work in both of these areas can be further pursued in a progressive, sustained and complementary manner, without undermining existing legal obligations”7 while recognizing that such nonbinding measures are not a substitute for legally binding arms control instruments.

Even so, a handful of states maintain the position that there can be no other way but the legally binding way. Such an all-or-nothing approach is unrealistic in light of today’s international security and diplomatic realities. What is more concerning is that the technologically less developed and resourceful countries likely will bear the brunt of the damage and disadvantage arising from the vacuum of norms, rules, and principles because they will not be in position to protect their rare assets in space by themselves. As such, the handful of resistant states is preventing the international community from collectively safeguarding the world by addressing and mitigating current and future space-related threats. A few states have abused the rule of consensus to effectively veto anything that deviates from their own legally-binding instruments, including the title of the working group itself. What states ought to be engaging in is multilateral consensus-driven negotiations to reach agreements on vital issues of common interest, thus guaranteeing the peace and predictable governance of outer space.

Even so, a handful of states maintain the position that there can be no other way but the legally binding way. Such an all-or-nothing approach is unrealistic in light of today’s international security and diplomatic realities. What is more concerning is that the technologically less developed and resourceful countries likely will bear the brunt of the damage and disadvantage arising from the vacuum of norms, rules, and principles because they will not be in position to protect their rare assets in space by themselves. As such, the handful of resistant states is preventing the international community from collectively safeguarding the world by addressing and mitigating current and future space-related threats. A few states have abused the rule of consensus to effectively veto anything that deviates from their own legally-binding instruments, including the title of the working group itself. What states ought to be engaging in is multilateral consensus-driven negotiations to reach agreements on vital issues of common interest, thus guaranteeing the peace and predictable governance of outer space.

In light of the gravity and urgency of this issue, the open and inclusive platform provided by the working group must continue. Although the group of governmental experts8 will begin on November 20 in Geneva and provide another useful platform for discussing security in outer space, its closed setting, allowing only 25 national representatives as expert participants, cannot substitute for the working group in which all UN member-states and civil society can participate.

The next working group will need to pursue further in-depth discussions on concrete measures to reduce space threats in the form of voluntary yet politically binding pledges. Nevertheless, should the rule of consensus once again prove prohibitive to forging viable agreement on norms, rules, and principles of responsible behaviors governing space security, the international community should consider manifesting their shared interest in the form of a cooperative group in which states participate voluntarily. The benefits of this partnership would be shared mutually by the participating states but not extended to nonparticipants. If those countries willing to act responsibly can agree on concrete measures that allow such benefit sharing and if nonadmission proves disadvantageous to nonparticipants, such a cooperative has the potential to eventually incorporate large numbers of countries, ultimately leading to a viable, relevant, and sustainable set of international norm, rules, and principles.

The benefits of these responsible behaviors could include many elements in the chair’s draft report: notifying and consulting each other before space launches, conducting rendezvous and proximity operations, jamming or spoofing of signals, refraining from any acts that would impair the provision of critical space-based services to civilians, and sharing information on possible breaches of such actions by private sector actors. Another important outcome of such a cooperative could be the establishment of routine channels of communications to share information and to continue shaping the list of responsible behaviors. Sharing of real-time information on space situational awareness through a joint project or joint burden sharing could be another exclusive benefit that can be reaped by participants.

This type of cooperation would be possible because, unlike most traditional arms control arrangements, the novel approach taken by the working group is based on behaviors and not capabilities per se. If prohibitions or restrictions on development, acquisition, deployment, testing, or use of certain space and counterspace capabilities become the focus, it would be extremely difficult to establish such norms because there always would be the fear of cheating by nonparticipants or even participants due to the lack of a verification regime. This is another important contribution that the working group approach can make to the shared international efforts.

What is most important is to continue this important work. Disagreement over the working group title prevented the release of an official report, but it should not derail the international community from getting back to the right orbit.

Norms alone are not the silver bullet that will solve all problems, but they are undeniably an indispensable component of future space security governance. As UN Secretary-General António Guterres rightly pointed out at the UN Security Council meeting on April 24, states must recommit to make the prevention of conflict and crises a priority. Outer space is a critical realm that requires the revival of multilateralism before the damage becomes irreversible and out of control.

ENDNOTES

1. The eight members in opposition were China, Cuba, Iran, Nicaragua, North Korea, Russia, Syria, and Venezuela.

2. For instance, 32 international organizations, commercial actors, and civil society organizations attended the working group, along with an open invitation for all UN member states. See UN General Assembly, “List of Other International Organizations, Commercial Actors and Civil Society Organizations Attending the Open-Ended Working Group, in Accordance With Resolution 76/231,” A/AC.294/2023/INF.2, August 31, 2023.

3. See Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and

Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, January 27, 1967, 610 U.N.T.S. 205.

4. For example, see UN Office for Outer Space Affairs, “Status of International Agreements Relating to Activities in Outer Space,” n.d., https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/treaties/status/index.html (accessed October 20, 2023).

5. Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, “Guidelines for the Long-Term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities,” A/AC.105/2018/CRP.20, June 27, 2018.

6. UN General Assembly, “Draft Report of the Open-Ended Working Group on Reducing Space Threats Through Norms, Rules and Principles of Responsible Behaviours,” A/AC/294/2023/CRP.1/Rev.1, August 31, 2023.

8. UN General Assembly, “Further Practical Measures for the Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space,” A/RES/74/34, December 18, 2019.

Il-hoon Kim, South Korea’s deputy permanent representative to the Conference on Disarmament in Geneva, is a former director of the Disarmament and Nonproliferation Division of the South Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The author’s opinions are his own and may not reflect the position of the South Korean government.