The Case for Strengthening Transparency in Conventional Arms Transfers

November 2022

By Paul Holtom, Anna Mensah, and Ruben Nicolin

Every year, more than $100 billion worth of weapons are transferred to countries and other buyers all over the globe. Most of these international transactions happened in the shadows until 1991, when there was a concerted effort to ensure a measure of transparency about who is buying, who is selling, and what weapons are involved in the world’s deadliest conflicts.

Although news reports and press releases provide the public with information on some orders and deliveries of conventional arms, fewer states are publicly reporting on their arms transfers compared to 10 or 20 years ago. If not for reporting by the world’s largest exporters of conventional arms on their activities, multilateral instruments designed to provide transparency on international arms transfers would be almost worthless. All of this raises the questions of what happened to the promise of those multilateral instruments, the UN Register of Conventional Arms (UNROCA) and the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), and what can be done to reverse the decline in reporting on arms exports and imports.

Although news reports and press releases provide the public with information on some orders and deliveries of conventional arms, fewer states are publicly reporting on their arms transfers compared to 10 or 20 years ago. If not for reporting by the world’s largest exporters of conventional arms on their activities, multilateral instruments designed to provide transparency on international arms transfers would be almost worthless. All of this raises the questions of what happened to the promise of those multilateral instruments, the UN Register of Conventional Arms (UNROCA) and the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), and what can be done to reverse the decline in reporting on arms exports and imports.

Tracking Conventional Arms

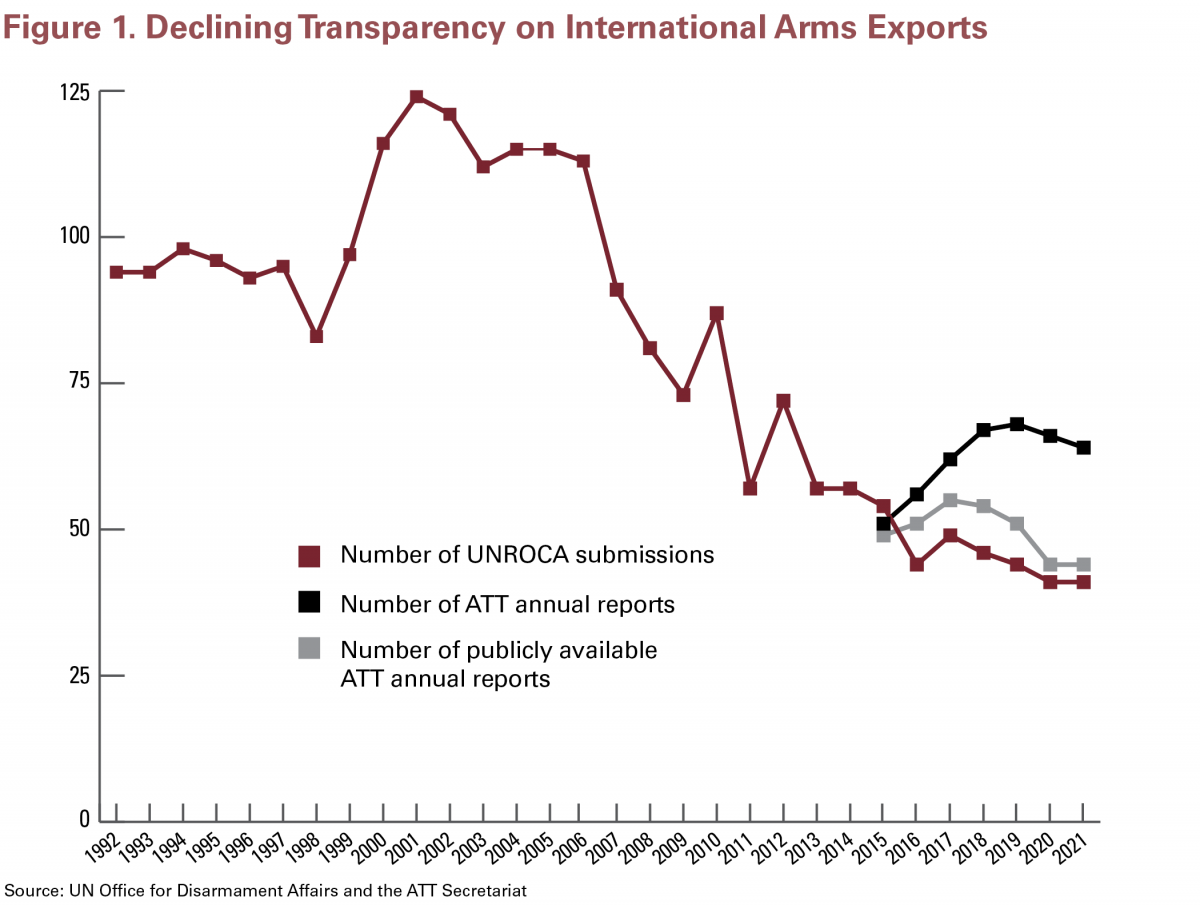

Thirty years ago, in December 1991, against the backdrop of Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, UN member states established the UNROCA “to prevent excessive and destabilizing accumulation of arms [and] enhance confidence, promote stability, help states to exercise restraint, ease tensions, and strengthen regional and international peace and security.”1 By the turn of the millennium, more than 120 UN member states were providing information annually for the register on their imports and exports of seven categories of conventional arms: tanks, armored vehicles, large-caliber artillery systems, combat aircraft and unmanned combat aerial vehicles, attack helicopters, warships, and missiles and missile launchers (fig. 1). In addition, several states provided what is labeled “background information” in their annual submission on the number of conventional weapons that their national armed forces acquired from domestic arms production, as well as how many major conventional weapons systems are in their national inventory. The norm of transparency in international arms transfers appeared to be well established as the information provided by states was made publicly available by the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs.

To ensure the relevance and effectiveness of the register, a review mechanism was established under which the UN secretary-general appoints a group of governmental experts every three years to evaluate its operation and make proposals for further development. Each group determines if new weapons systems need to be included in national submissions to the register. It also looks at ways to promote participation in the register and how to use submitted information to build confidence and security among states.

In the spring and summer of 2022, the most recent experts group noted that its triennial review “took place against a backdrop of heightened international tension and mistrust, which underlined the continued relevance of the register and highlighted once again the continuing need for transparency and confidence-building instruments in political and military affairs.”2 Although there has been a dramatic downward trajectory in register reporting for more than a decade, the group lamented that it was meeting at a time when only 37 states had submitted their 2021 data to the register, compared to 124 submissions in 2001.3 It is time for new ideas to reinvigorate the move toward more and better transparency on the international arms trade.

Transparency in Decline

Sharing information on military capabilities with other states and making it available to the public has long been a sensitive issue for government officials and security personnel. Yet, since the end of the Cold War, transparency in international arms transfers looked to have been widely accepted. About 170 UN member states, more than three-quarters of the total, have participated in the register at least once.

Furthermore, the register has served as a point of reference and inspiration for regional confidence-building and information exchanges on international arms transfers in Africa, the Americas, and Europe. For example, states participating in the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe have exchanged annual reports on their imports and exports of conventional arms using UNROCA descriptions since 1998.4 States-parties to the Inter-American Convention on Transparency in Conventional Weapons Acquisitions, which entered into force in November 2002, are obliged to submit annual reports on imports and exports of items falling within the seven categories established by the UNROCA.5 Most recently, the register served as a key point of reference for the ATT, which obliges states-parties to report annually on their exports and imports of seven categories of major conventional weapons and also small arms and light weapons. Article 13(3) of the ATT even encourages states-parties to provide the same information for the ATT and the register.

UNROCA reporting levels logically might be expected to exceed those for the ATT because all UN member states are called on to participate in the register, whereas just more than half of these states are obliged to report on international arms transfers to the ATT Secretariat. Yet, almost from the start, ATT annual reporting rates have been higher than those for the register. Whereas all submissions to the UNROCA are available publicly, ATT states-parties can opt for their annual reports to be made available only to other ATT states-parties. In the first year of ATT reporting, two reports were made available for ATT states-parties only, while the other 52 reports were publicly available. By contrast, of the 64 ATT states-parties that submitted their annual report for 2021 by October 12, 2022, 20 states (31 percent) had chosen not to make their report publicly available.6 The figures for publicly reporting on arms exports and imports today look very similar to the 41 UNROCA submissions in the online database at the end of September 2022 and 44 ATT annual reports publicly available for 2021. Thus, a larger number of ATT states-parties prefer to provide information on their arms transfers only to other states. So, it is not just the register that is failing to expand public reporting on international arms transfers, as more ATT states are seeking to keep their transfers out of the public eye. This looks like a broader problem.

UNROCA reporting levels logically might be expected to exceed those for the ATT because all UN member states are called on to participate in the register, whereas just more than half of these states are obliged to report on international arms transfers to the ATT Secretariat. Yet, almost from the start, ATT annual reporting rates have been higher than those for the register. Whereas all submissions to the UNROCA are available publicly, ATT states-parties can opt for their annual reports to be made available only to other ATT states-parties. In the first year of ATT reporting, two reports were made available for ATT states-parties only, while the other 52 reports were publicly available. By contrast, of the 64 ATT states-parties that submitted their annual report for 2021 by October 12, 2022, 20 states (31 percent) had chosen not to make their report publicly available.6 The figures for publicly reporting on arms exports and imports today look very similar to the 41 UNROCA submissions in the online database at the end of September 2022 and 44 ATT annual reports publicly available for 2021. Thus, a larger number of ATT states-parties prefer to provide information on their arms transfers only to other states. So, it is not just the register that is failing to expand public reporting on international arms transfers, as more ATT states are seeking to keep their transfers out of the public eye. This looks like a broader problem.

For the UNROCA, the dramatic decline in participation corresponds with a lack of countries submitting a “nil return,” that is, countries with no imports or exports of major conventional arms to report but that still participate in the register by declaring nothing to report. The annual average number of nil returns in 2000–2003 was 59 percent of submissions compared to 10 percent for 2020.7 The 2022 register experts group identified several factors to explain this, including limited capacities and lack of dedicated personnel for collecting and compiling data for submissions in national administrative structures and a lack of commitment to the register because it does not directly appear to link with their national security priorities, such as countering terrorism or organized crime. Other possible factors are an increasing burden on states that have multiple reporting obligations and limited capacity of the UNROCA Secretariat to encourage and support expanded participation.8

The Role of Major Arms Exporters

Despite the fact that an increasing number of countries are producing conventional weapons, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute estimates that the five largest arms exporting states accounted for 75 percent of the volume of international transfers of major conventional arms in 2012–2021, with the top 20 exporters accounting for 98 percent of that amount.9 All of the top 20 exporters in 1992–2021 have reported at least once to the register, with half of these states submitting information for at least 27 of the 30 years for which register submissions have been due. In addition, the 15 largest exporters that are also ATT states-parties have a 100 percent reporting record when it comes to ATT annual reports. Therefore, even though overall UNROCA reporting rates are in decline, the world’s largest arms exporters, in many cases due to requirements in national law or regulations, are still supporting the transparency norm and hopefully providing a reliable overview of the global flow of conventional arms.

At the same time, the quality of the information provided by these global leaders in arms exports varies. China and Russia only provide data on the number of items exported for each register category. For example, although Russia reported that it delivered 12 combat aircraft to Vietnam in 2021, it did not identify the type of aircraft. In contrast, Belarus reported the delivery of four MiG-29 jet fighters to Serbia that same year. Without this qualitative information, the utility of register submissions for confidence-building purposes is limited.

Although the Chinese and Russian approaches to reporting arms transfers have not changed in the past 30 years, other major exporters have altered their reporting practices and not always for the better. The Small Arms Survey’s Small Arms Trade Transparency Barometer, which has tracked the information provided by major small arms exporters for the past 20 years, found that some former transparency leaders, notably France, Italy, Norway, and Sweden, now publish less detailed information on arms exports.10 Meanwhile, the war in Ukraine could have a further detrimental impact on the transparency of several of the world’s largest arms exporters. The situation is dynamic and subject to change, but one could expect that states supplying conventional arms to Ukraine would not want the details to be made publicly available as they could reveal insights about Ukrainian military capabilities. Germany did not provide details about military materiel sent to Ukraine earlier this year, although it now regularly updates a governmental website with data on conventional arms and ammunition delivered to Ukraine, as well as planned transfers.11 France, Japan, Portugal, and Spain have announced plans to assist Ukraine militarily, but have not officially provided specific data on the arms and ammunition being delivered.12 It is a real question as to how forthcoming these states will be when it comes to filing their ATT annual reports or register submissions in 2023.

Improving Transparency and Accountability

Some initiatives to improve transparency and accountability are underway, but more are needed. For example, in 2021 the seventh ATT conference of states-parties agreed that the parties can instruct the treaty secretariat to provide relevant information contained in the ATT annual report to the UNROCA Secretariat to be used for register submissions.13 In other words, an ATT state-party can prepare and submit one report on arms transfers and satisfy both its treaty reporting obligation and its register commitment. As of mid-October, 18 ATT states-parties that had made their annual reports publicly available for 2021 indicated that they could be used in such a manner.14 It appears that 11 of these states already are included in UNROCA figures, so the total number of submissions should be increased from 40 to 47 for 2021. Although this approach may not push the number of register submissions above the total number of ATT annual reports for this year, it has already made a difference in its first trial year and could encourage others to use the same approach in the future.

The 2022 UNROCA experts group and the ATT working group on transparency and reporting have proposed other good ideas for building national capacities to enable data collection and processing to compile complete submissions for the register and ATT annual reports. These ideas include providing more support to people appointed by governments to coordinate the report compiling processes, including by offering international cooperation and assistance. These groups have stressed the benefits of data sharing for increasing trust and building confidence among states. It is expected that by examining reports and engaging with states and international and regional organizations, it will be possible to identify in advance potential risks for conflict and illicit diversion.

The information contained in ATT annual reports and the register should be for bilateral and multilateral consultations on situations where there is a potential of arms transfers posing a risk to international and regional security. Such exchanges are usually confidential, but occasionally cases come to light in which information provided to the register can highlight concerns and prompt action to address diversion or arms fueling conflicts. Perhaps the highest profile case was in 2008 when a vessel transporting new military materiel from Ukraine to Kenya was seized by pirates. This occurred shortly after Ukraine provided information in its 2007 register submission on its delivery of tanks, artillery, and small arms to Kenya. Investigations by journalists and arms specialists engaged with the United Nations determined that at least some of the arms and ammunition to Kenya were diverted to South Sudan. In this case, Ukraine’s register submission provided information that was not only used in confidential bilateral consultations, but also enabled a public debate on accountability in Kenyan arms transfer activities because the information was publicly available.

It is critical that efforts to increase public reporting on international arms transfers address the specific challenges faced by individual states, rather than adopting a one-size-fits-all approach. The benefits derived from this transparency process and the administrative burden that reporting imposes can be very different from one state to another. At the same time, capacity-building assistance alone will not lift the level of reporting on international arms transfers.

Transparency for All

The UNROCA was premised on an understanding that transparency in arms transfers builds confidence among countries and can provide some warning if excessive or destabilizing accumulations of arms are taking place. As long as major arms exporters continue to report regularly on their conventional transfers, it will be possible to discern and address trends in international arms transfers that could be problematic.

Yet, the register is also intended to build confidence among states that are not major arms exporters. Although many states submitted a nil return 20 years ago, the commitment of these states has dwindled. For Latin America and the Caribbean, the level of participation has dropped dramatically, and there have been no African submissions for several years. Notably, states from these regions submit ATT annual reports, but are not participating in the UNROCA.

One of the main reasons given for the difference in reporting is that the ATT includes small arms and light weapons in its scope, and this has not always been the case for the register. Almost all states are involved in the international transfer of these weapons on a regular basis, and many have highlighted the illicit trade in this category as a pressing security challenge. Increasing transparency about these international transfers could help demonstrate that the register can meet the security needs of more states.

To address that weakness, every UNROCA experts group has discussed whether to include small arms and light weapons as an eighth reporting category, mirroring the ATT. Since 2003, UN member states have been invited to provide information on international transfers of these weapons, but this category is treated as a lower-level commitment than reporting on exports and imports of artillery, combat aircraft, and tanks. In the search for creative options to fix the problem, the 2016 experts group created a formula designed to encourage “states in a position to do so” to provide information on international transfers in this underreported small arms category. Small arms and light weapons do not yet constitute a formal new category, but the slow elevation of their status should mean that most states will have to report on at least some of these transfers in their UNROCA submission and that the register is beginning to reflect broader security concerns than just those that were most acute 30 years ago.

Another challenge for the register is that although it requires states to report on imports and exports, states can also acquire conventional arms through national production. States are encouraged to provide information to the register on weapons acquired from indigenous production, but only four did so in this year’s submission. Every register experts group has discussed upgrading the reporting on procurement through national production so that this method of arms acquisition is treated similarly to imports and exports. Such a change could demonstrate that the register does not require states that import or export conventional arms to be more transparent than those that produce their own. Removing this discriminatory element might not result in a dramatic increase in register participation, but it would ensure that the register can more accurately capture the different ways in which states strengthen their military capabilities.

Conventional arms continue to be the main weapons used in conflicts around the world, causing untold deaths and destruction and setting back the socioeconomic development of vulnerable populations. Although open sources, journalists, and specialized arms investigators provide valuable information on weapons flows into conflict areas, it is public reporting by states that can provide a comprehensive, accurate picture of international arms transfers and in this way foster genuine trust and confidence-building among states. Such transparency remains as important for international peace and security today as it was 30 years ago.

ENDNOTES

1. UN General Assembly, A/RES/46/36, December 6, 1991.

2. UN General Assembly, “Continuing Operation of the United Nations Register of Conventional Arms and Its Further Development: Note by the Secretary-General,” A/77/126, June 30, 2022, para. 88.

3. A UN report published in the summer of 2022 indicated that only 37 member states had participated in the register. By September 2022 the online database indicated that 41 member states have provided information. UN General Assembly, A/77/165, July 14, 2022, https://front.un-arm.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/A-77-165-UN-Register-of-Conventional-Arms-002.pdf; UNROCA, Transparency in the global reported arms trade, https://www.unroca.org/.

4. Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, FSC.DEC/13/97, July 16, 1997, https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/8/3/453696.pdf.

5. OAS, CITAAC. Most national reports can be found online at: https://www.oas.org/csh/english/conventionalweapons.asp.

6. Arms Trade Treaty, “Annual Reports,” October 5, 2022, https://thearmstradetreaty.org/annual-reports.html?templateId=209826.

7. UN General Assembly, “Continuing Operation of the United Nations Register of Conventional Arms and Its Further Development,” para. 28.

9. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, “SIPRI Arms Transfers Database,” March 14, 2022, https://www.sipri.org/databases/armstransfers.

10. Small Arms Survey, “The Small Arms Trade Transparency Barometer,” February 21, 2020, https://www.smallarmssurvey.org/database/small-arms-trade-transparency-barometer.

11. Federal Government of Germany, “Military Support for Ukraine,” October 11, 2022, https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/news/military-support-ukraine-2054992.

12. For publicly available information on commitments and deliveries of conventional arms and ammunition to Ukraine in 2022, see Arianna Antezza et al., “The Ukraine Support Tracker: Which Countries Help Ukraine and How?” Kiel Working Paper, No. 2218, August 2022, https://www.ifw-kiel.de/fileadmin/Dateiverwaltung/IfW-Publications/-ifw/Kiel_Working_Paper/2022/KWP_2218_Which_countries_help_Ukraine_and_how_/KWP_2218_Version5.pdf; Kiel Institute for the World Economy, “Ukraine Support Tracker,” October 11, 2022, https://www.ifw-kiel.de/topics/war-against-ukraine/ukraine-support-tracker/; Claire Mills, “Military Assistance to Ukraine Since the Russian Invasion,” House of Commons Library Research Briefing, No. 9477, October 17, 2022, https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9477/CBP-9477.pdf.

13. Arms Trade Treaty Secretariat, “Final Report,” ATT/CSP7/2021/SEC/681/Conf.FinRep.Rev1, September 2, 2021; Arms Trade Treaty Working Group on Transparency and Reporting, “Co-Chairs’ Draft Report to CSP7,” ATT/CSP7.WGTR/2021/CHAIR/676/Conf. Rep, July 22, 2021.

14. Dumisani Dladla, “Arms Trade Treaty: Status of Reporting” (presentation, August 24, 2022), https://www.thearmstradetreaty.org/hyper-images/file/ATT_CSP8_ATTS_Status%20of%20Reporting/ATT_CSP8_ATTS_Status%20of%20Reporting.pdf.

Paul Holtom, head of the Conventional Arms and Ammunition Programme at the UN Institute for Disarmament Research, has been a consultant to the 2013, 2016, 2019, and 2022 groups of governmental experts on the UN Register of Conventional Arms. Anna Mensah is an associate researcher with the program, focusing on weapons and ammunition management, arms transfers, and diversion prevention. Ruben Nicolin is a graduate professional with the program, focusing on weapons and ammunition management, transparency, and reporting.