“For half a century, ACA has been providing the world … with advocacy, analysis, and awareness on some of the most critical topics of international peace and security, including on how to achieve our common, shared goal of a world free of nuclear weapons.”

The Biden Nuclear Posture Review: Obstacles to Reducing Reliance on Nuclear Weapons

January/February 2022

By Adam Mount

President Joe Biden entered office with two objectives for nuclear weapons policy: declaring that “the sole purpose of our nuclear arsenal should be to deter—and, if necessary, retaliate against—a nuclear attack” and implementing the sole purpose policy as part of a broader effort to reduce the role of nuclear weapons. Although Biden has not clearly defined either goal, his support for both has signaled an intention to produce a significant shift in U.S. nuclear weapons policy. Public hints about the structure and the content of his administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) suggest, however, that Biden will not achieve his goal of reducing reliance on nuclear weapons in U.S. plans and posture.

If Biden’s NPR walks back these commitments, it would be only the latest example of a president trying and failing to reduce the nation’s reliance on nuclear weapons. This pattern is the result of concerted opposition from partisan opponents and Pentagon officials, structural impediments to the president’s ability to shift policy, and the failure of political appointees to learn the lessons of past attempts. Even more than in previous nuclear policy reviews, these trends have been publicly visible throughout the 2022 NPR process and represent a cautionary tale for future administrations.

If Biden’s NPR walks back these commitments, it would be only the latest example of a president trying and failing to reduce the nation’s reliance on nuclear weapons. This pattern is the result of concerted opposition from partisan opponents and Pentagon officials, structural impediments to the president’s ability to shift policy, and the failure of political appointees to learn the lessons of past attempts. Even more than in previous nuclear policy reviews, these trends have been publicly visible throughout the 2022 NPR process and represent a cautionary tale for future administrations.

The Past as Prologue

For Biden, the 2022 NPR process is a familiar story. With Biden at his side, President Barack Obama entered office in 2009 also determined to reduce the nation’s reliance on nuclear weapons. Although this was the subject of his first major international address, Obama did not come equipped with a firm plan for how to do it. He left the issue up to the NPR process. For example, the Obama review explicitly did not adopt the concept of sole purpose as the role of nuclear weapons although it promised to “work to establish conditions under which such a policy could be safely adopted.”1 Instead, the review stated that the United States “would only consider the use of nuclear weapons in extreme circumstances to defend the vital interests of the United States or its allies and partners.”2 The administration reopened the question of the sole purpose concept in its last year in office, but Obama’s secretaries of defense, state, and energy all argued against it.3

In January 2017, nine days before he would leave office, Vice President Biden delivered a wistful speech to a Washington audience, reporting that “the President and I strongly believe we have made enough progress” toward creating the conditions for the sole purpose doctrine.4 Despite their conviction, they had not made the change. After eight years, the U.S. nuclear arsenal was still configured to deter the same threats for the same reasons.

The 2018 NPR reversed course and instead took steps to increase the nation’s reliance on nuclear weapons. Worried that adversaries could conduct a limited nuclear strike for coercive purposes, the Trump administration argued that new nuclear weapons were the answer. The 2018 review proposed new low-yield warheads, a new sea-launched cruise missile, and a delay in retiring the last megaton-class gravity bomb. That review also produced new language warning that the United States would consider employing a nuclear weapon in response to a “non-nuclear strategic attack,” a vague phrase the administration never defined. After critics warned that the new policy could permit a nuclear response to a cyberattack, officials hastened to dispute the claim, but never really clarified it.5 To this day, it is not clear who wrote the document. In short, it was not the kind of process that the Biden team should want to emulate.

In the past year, former President Donald Trump’s allies and advisers have worked hard to prevent the Biden administration from revisiting these decisions. Instead, they apparently hoped the new team could be coerced or cajoled into abandoning Biden’s stated goals and reaffirming the Trump policy.6 In a series of hyperbolic articles, they have argued that any change to U.S. policy would alarm allies and embolden adversaries, despite the fact that the Biden administration has not fully articulated its policy. According to this view, raising the bar for a U.S. nuclear response would give a green light to attacks that fall below that bar. Rather than engaging with any specific formulation of the sole purpose doctrine, these arguments tend to conflate the policy with a no-first-use strategy and object generally to any related change in existing policy.7

In October, former Trump administration officials released a declassified document that was required to report on presidential guidance for nuclear employment plans that had been issued in April 2019.8 Although legally required to inform Congress of the change before it occurred, the outgoing team only sent the document to Capitol Hill in December 2020, after Trump lost the election. It is a strikingly partisan document that explicitly refutes policies to which Biden had committed on the campaign trail by arguing that “the United States sees no benefit and significant risk in adopting a ‘sole purpose’ policy” and claiming that doing so “would dispirit allies and partners.”9 The document does not provide Congress with information about Trump’s employment guidance, but rather serves as a handbook for civil servants, military officials, and sympathetic officials in allied countries who intended to resist Biden administration policies. It is more a partisan strategy than a nuclear strategy.

In October, former Trump administration officials released a declassified document that was required to report on presidential guidance for nuclear employment plans that had been issued in April 2019.8 Although legally required to inform Congress of the change before it occurred, the outgoing team only sent the document to Capitol Hill in December 2020, after Trump lost the election. It is a strikingly partisan document that explicitly refutes policies to which Biden had committed on the campaign trail by arguing that “the United States sees no benefit and significant risk in adopting a ‘sole purpose’ policy” and claiming that doing so “would dispirit allies and partners.”9 The document does not provide Congress with information about Trump’s employment guidance, but rather serves as a handbook for civil servants, military officials, and sympathetic officials in allied countries who intended to resist Biden administration policies. It is more a partisan strategy than a nuclear strategy.

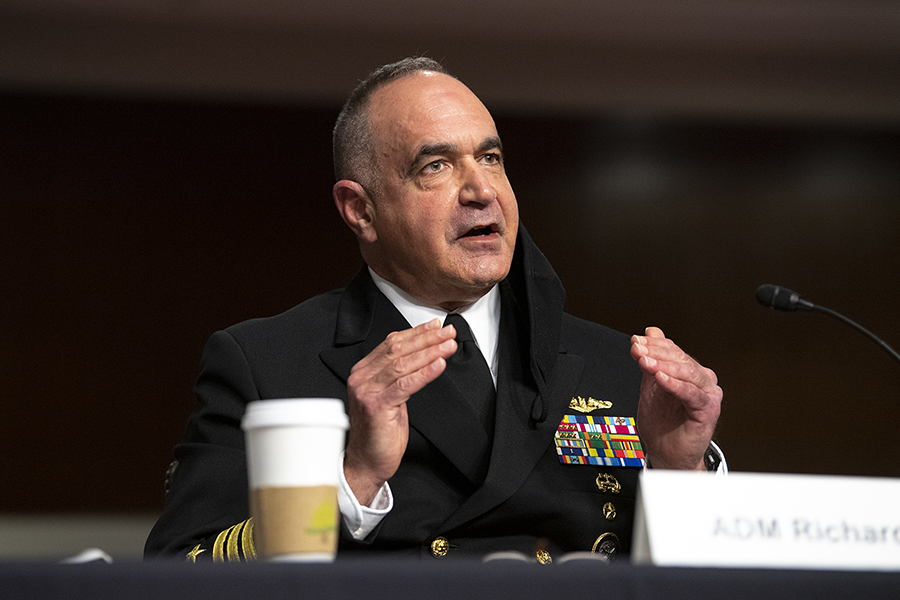

Consistent with that document, Admiral Charles Richard, who oversees the nation’s nuclear forces, said that the purpose of Biden’s NPR should be “validation, that we like the strategy we have.”10 With that perspective, Richard went before Congress in April to argue against options that the Biden administration was then considering, including a sole purpose policy and any changes to existing plans for acquiring new weapons.11 Further, an unnamed Pentagon official stated that it was “not likely” that sole purpose or no-first-use policies will be presented as options.12

Closing Off Options

This campaign effectively is an attempt to deprive Biden of the ability to set his own nuclear weapons policy. In this context, it would require a concerted effort to advance the president’s objectives. In practice, the Biden administration has taken steps in the structure and staffing of the review that further constrain its ability to pursue the president’s goals.

Biden’s first budget request, submitted in April, was an early opportunity to build leverage and set the tone of the review. Rather than pause or cancel questionable programs to preserve decision space, the request fully supported Trump’s accelerated schedule to procure new air-launched cruise missiles and continue developing a new sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM) and the low-yield submarine-launched warhead that Biden had called “a bad idea” during the campaign. The budget request is 28 percent higher than projected two years ago.13 These decisions guaranteed that the default position in the NPR would be to retain the existing policy, ensuring that debate would center around low-hanging fruit such as the SLCM that had been carefully positioned by the previous administration to divert attention from other policies.

The crucial moment for an administration seeking to shift nuclear weapons policy comes when the National Security Council (NSC) issues presidential guidance to initiate, indicate the president’s expectations for, and structure the NPR. For the Biden administration, this took the form of a public interim national security guidance document and a classified presidential study directive. Neither document referred to a sole purpose policy directly. Rather than explicitly direct that the Pentagon develop the president’s preferred options, the guidance was negotiated among a range of offices across the government, including officials from the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Meanwhile, there is no political appointee on the NSC staff empowered to represent and interpret the president’s guidance in the NPR process. Instead, the responsibility is divided between the offices of the NSC senior directors for defense and nuclear issues. The director for strategic capabilities in the defense office is customarily a uniformed general officer and so will tend to be more comfortable implementing settled policy than defining a shift in policy such as a sole purpose policy.

In the months leading up to the NPR, Leonor Tomero, the deputy assistant secretary of defense in charge of managing the review, came under fire from Senate Republicans and civil servants who worried that her views were too progressive.14 In particular, she was accused of favoring the sole purpose declaration that Biden supported and had written into the Democratic party platform. Rather than defend her, Pentagon leadership showed her the door, saying she was removed as part of a larger reorganization.15

In the months leading up to the NPR, Leonor Tomero, the deputy assistant secretary of defense in charge of managing the review, came under fire from Senate Republicans and civil servants who worried that her views were too progressive.14 In particular, she was accused of favoring the sole purpose declaration that Biden supported and had written into the Democratic party platform. Rather than defend her, Pentagon leadership showed her the door, saying she was removed as part of a larger reorganization.15

The Biden administration began its NPR in July with the intention to release its report in January, along with the National Defense Strategy.16 Tomero’s removal meant there was no Pentagon political appointee in the NPR process who was prepared to implement the president’s sole purpose policy. Following Tomero’s departure, the NPR was led by Assistant Secretary of Defense Melissa Dalton and Richard Johnson, the deputy assistant secretary tasked with preventing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, who also served in an acting capacity in Tomero’s previous role, despite the apparent reorganization. Even capable officials such as Dalton and Johnson will have difficulty influencing the highly politicized and complex debates of nuclear weapons policy without experience with those arguments, without a portfolio that allows them to focus their full attention on the review, and without clear guidance from the president.

As a result, the administration has been unable to engage in a complete discussion on a sole purpose policy with allies, many of whom have been understandably apprehensive about potential shifts in an established U.S. policy. With firm guidance from the president and a concerted effort to adjust policy, U.S. officials might have engaged allies on their concerns about specific proposals. Without firm presidential guidance, allies have been left to fret about undefined concepts and rumors, allowing opponents of the president’s objectives in the Pentagon, Congress, and outside of government an opening to flood allies with misleading speculation. This mix of uncertainty and misinformation created an environment that made it easy for Pentagon political appointees to avoid serious consideration of the sole purpose issue altogether.

The administration also complicated the NPR process by folding nuclear weapons policy into a concept of “integrated deterrence.” The concept held considerable promise for Biden’s stated objectives for the review. If the United States was to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons, an integrated review could examine the utility and credibility of nuclear and non-nuclear options for performing specific missions and identify ways to safely reduce reliance on nuclear weapons.17 In principle, an integrated review could also communicate the benefits of Biden’s goals to allies, demonstrating how reduced reliance could lead to increased credibility in the overall U.S. deterrence posture.

The 2022 NPR and the National Defense Strategy did not undertake this assessment. There is no indication that the strategy was tasked with reducing reliance on nuclear weapons, and the bureaucratic silos that have divided the NPR and the broader National Defense Strategy remain intact. Instead, combining the documents could decrease the transparency of nuclear policy, concealing areas where the review failed to reach agreement or advance the president’s objectives. An integrated review that does not engage with the difficult questions of operational plans and posture might reduce the word count assigned to nuclear weapons policy, but not the missions assigned to the weapons.

The 2022 NPR and the National Defense Strategy did not undertake this assessment. There is no indication that the strategy was tasked with reducing reliance on nuclear weapons, and the bureaucratic silos that have divided the NPR and the broader National Defense Strategy remain intact. Instead, combining the documents could decrease the transparency of nuclear policy, concealing areas where the review failed to reach agreement or advance the president’s objectives. An integrated review that does not engage with the difficult questions of operational plans and posture might reduce the word count assigned to nuclear weapons policy, but not the missions assigned to the weapons.

Without firm presidential guidance, staff empowered to implement that guidance, and a detailed examination of the utility of nuclear and non-nuclear capabilities, the Pentagon is unlikely to produce a policy that significantly reduces reliance on nuclear weapons. The administration evidently acquiesced in a broad effort to undermine the president’s stated objectives and his ability to set policy. As it stands, the 2022 NPR will not only preserve the nation’s reliance on nuclear weapons, but if its practices are adopted by future administrations, will make it more difficult to accomplish the goal in coming years.

The Path Forward on Reducing Reliance

It is still possible that the administration could adjust declaratory policy through other means. The undersecretary of defense for policy or the national security adviser could choose to rewrite the NPR material or make significant amendments at the 11th hour, similar to the process that occurred in the 2010 NPR. Although such intervention might further Biden’s stated objectives, it would also underline that the NPR failed to perform that task and that the review process had to be circumvented to adjust policy. Furthermore, the administration should avoid last-minute changes that are simply cosmetic. Declaratory policy is consequential and credible to the extent that it reflects a strategy that shifts reliance away from nuclear weapons in operational plans.

Nevertheless, one option is to declare that the United States would use nuclear weapons only in the event of an “existential attack” against the United States or its allies.18 Although Colin Kahl, undersecretary of defense for policy, spoke approvingly about this possibility in the spring of 2021, the formulation raises its own questions. Could a cyberattack or chemical weapons attack ever threaten the existence of an ally? Would attacks that leave U.S. allies intact but exposed to subsequent attacks count as existential? These questions permit widely divergent interpretations by allies and adversaries and, depending on the exact language in the document and the statements of U.S. officials, might fail to raise the bar significantly for nuclear use.

The administration will have another opportunity to adjust nuclear weapons policy when it drafts its own nuclear employment guidance over the next year or two. This could serve as an opportunity to translate shifts in declaratory policy into operational plans and require planners to develop more credible, flexible nonnuclear options for specific contingencies. This would require a more active and directed employment guidance process than in previous years. Without fixing the decisions that constrained the NPR process, it will be even more difficult to affect the complex and parochial planning process. It will require that the president issues clear implementation guidance if he selects new declaratory language and empowers expert officials to create a significant change in strategy.

An administration committed to reducing reliance on nuclear weapons will have to learn three lessons from the 2022 NPR process if it is to succeed where its predecessors have failed. First, the president should issue clear guidance about what they want, including an explicit description of how to reduce nuclear reliance and what options should be developed and presented to the president for decisions. Second, the president will have to select and appoint expert officials to lead the NPR process who are ready to defend and implement that guidance. Third, civilian leaders must ensure that military officers, civil servants, and political appointees follow the president’s guidance and hold them accountable if they refuse to do so or attempt to subvert the review process, for example, if they mislead allies, undermine political appointees, or coordinate with the administration’s opponents in Congress. If Pentagon officials disagree with the president’s guidance, they have a duty to try to convince the president to change it, but they also have a duty to provide options requested by the president.

Whether or not Biden, confronted with political resistance or additional information, changed his mind on a sole purpose policy, the 2022 NPR demonstrates that the existing process for developing nuclear weapons policy is deeply flawed. Deputy National Security Advisor Jon Finer optimistically promised that “this is going to be the president’s posture review and the president’s posture.”19 It is also possible that, in his final days in office, Biden may find himself delivering another wistful speech lamenting that yet another administration has failed to establish a sole purpose policy as a guiding principle of U.S. nuclear policy or to significantly reduce reliance on nuclear weapons.

ENDNOTES

1. U.S. Department of Defense, “Nuclear Posture Review Report,” April 2010, p. 16, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/features/defenseReviews/NPR/2010_Nuclear_Posture_Review_Report.pdf.

3. David E. Sanger and William J. Broad, “Obama Unlikely to Vow No First Use of Nuclear Weapons,” The New York Times, September 6, 2016.

4. Office of the Vice President, The White House, “Remarks by the Vice President on Nuclear Security,” January 12, 2017, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2017/01/12/remarks-vice-president-nuclear-security.

5. George Perkovich, “Really? We’re Gonna Nuke Russia for a Cyberattack?” Politico, January 18, 2018, http://politi.co/2Dpp28s; Scott D. Sagan and Allen S. Weiner, “The U.S. Says It Can Answer Cyberattacks With Nuclear Weapons. That’s Lunacy.” The Washington Post, July 9, 2021; Patrick Tucker, “No, the U.S. Won’t Respond to a Cyber Attack With Nukes,” Defense One, February 2, 2018.

6. Eric Edelman and Franklin Miller, “President Biden, Don’t Help Our Adversaries Break NATO,” The Washington Post, November 4, 2021; Jim Risch, “The U.S. Must Reject a ‘Sole Purpose’ Nuclear Policy,” Defense News, October 25, 2021. Those arguments were mirrored by editorials boards and some Democratic politicians. “Folding America’s Nuclear Umbrella,” The Wall Street Journal, November 12, 2021; Seth Moulton, “We Must Eliminate Nuclear Weapons, but a ‘No First Use’ Policy Is Not the Answer,” The Hill, November 29, 2021, https://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/politics/583433-we-must-eliminate-nuclear-weapons-but-a-no-first-use-policy-is. Reports on allied concerns about President Joe Biden’s objectives featured prominently in arguments made by opponents and in media accounts of the review. Demetri Sevastopulo and Henry Foy, “Allies Lobby Biden to Prevent Shift to ‘No First Use’ of Nuclear Arms,” Financial Times, October 30, 2021.

7. Patty-Jane Geller, “What Experts and Senior Officials Have Said About Adopting a No-First-Use or Sole-Purpose Nuclear Declaratory Policy,” Heritage Foundation Factsheet, No. 219 (October 20, 2021), https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/FS219.pdf.

8. Robert Soofer and Matthew R. Costlow, “An Introduction to the 2020 Report on the Nuclear Employment Strategy of the United States,” Journal of Policy and Strategy, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Fall 2021): 2–8, https://nipp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/1.1R.pdf.

9. U.S. Department of Defense, “Report on the Nuclear Employment Strategy of the United States - 2020,” 2020, p. 8, https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/FOID/Reading%20Room/NCB/21-F-0591_2020_Report_of_the_Nuclear_Employement_Strategy_of_the_United_States.pdf.

10. Charles R. Richard and Ronald R. Fritzmeier, Remarks to the Defense Writers Group, January 5, 2021, https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/blogs.gwu.edu/dist/2/672/files/2021/01/DWG-Admiral-Charles-R.-Richard.pdf.

11. “To Receive Testimony on United States Strategic Command and United States Space Command in Review of the Defense Authorization Request for Fiscal Year 2022 and the Future Years Defense Program,” April 20, 2021, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/download/transcript2042021.

12. Bryan Bender and Lara Seligman, “Biden’s Nuclear Agenda in Trouble as Pentagon Hawks Attack,” Politico, September 23, 2021, https://www.politico.com/news/2021/09/23/leonor-tomero-pentagon-nuclear-hawks-513974.

13. Kingston Reif and Shannon Bugos, “Biden’s Disappointing First Nuclear Weapons Budget,” Arms Control Association Issue Brief, Vol. 13, No. 4 (July 9, 2021), https://www.armscontrol.org/issue-briefs/2021-07/bidens-disappointing-first-nuclear-weapons-budget.

14. “To Receive Testimony on the Department of Defense Budget Posture for Nuclear Forces in Review of the Defense Authorization Request for Fiscal Year 2022 and the Future Years Defense Program,” May 12, 2021, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/download/transcriptnuclear51221; Bryan Bender and Lara Seligman, “Biden’s Nuclear Agenda in Trouble as Pentagon Hawks Attack,” Politico, September 23, 2021, https://www.politico.com/news/2021/09/23/leonor-tomero-pentagon-nuclear-hawks-513974.

15. Lara Seligman, Alexander Ward, and Paul McLeary, “Pentagon’s Top Nuclear Policy Official Ousted in Reorganization,” Politico, September 21, 2021, https://www.politico.com/news/2021/09/21/pentagon-top-nuclear-official-ousted-reorganization-513502.

16. Kingston Reif, “Biden Administration Begins Nuclear Posture Review,” Arms Control Today, September 2021, pp. 26–27, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2021-09/news/biden-administration-begins-nuclear-posture-review.

17. Adam Mount and Pranay Vaddi, “An Integrated Approach to Deterrence Posture,” Federation of American Scientists, January 2021, https://fas.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/An-Integrated-Approach-to-Deterrence-Posture.pdf; Brad Roberts, “It’s Time to Jettison Nuclear Posture Reviews,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol. 76, No. 1 (2020): 31–36.

18. This formulation would presumably apply to nuclear attacks and other existential attacks in order to maintain an option to employ U.S. nuclear forces to prevent any nuclear attack, not only existential nuclear attacks. For a recently proposed version of this option, see George Perkovich and Pranay Vaddi, “Proportionate Deterrence: A Model Nuclear Posture Review,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 21, 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/01/21/proportionate-deterrence-model-nuclear-posture-review-pub-83576. This version specifies that nuclear weapons could be used “only when no viable alternative exists to stop” an existential attack in order to confine potential use to preemption of an attack and to accommodate the “nuclear necessity principle.” Jeffrey G. Lewis and Scott D. Sagan, “The Nuclear Necessity Principle: Making U.S. Targeting Policy Conform With Ethics and the Laws of War,” American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Fall 2016, https://www.amacad.org/publication/nuclear-necessity-principle-making-us-targeting-policy-conform-ethics-laws-war.

19. Emma Belcher, “Press the Button,” podcast, Ploughshares Fund, November 2, 2021, https://soundcloud.com/user-954653529/the-white-houses-jon-finer-on-all-things-nuclear.