The Power of Women Strike for Peace

November 2021

By Kathy Crandall Robinson

On November 1, 1961, an estimated 50,000 women in 60 U.S. cities answered a call to join a one-day strike with the rallying slogan “End the Arms Race—Not the Human Race.”1 Astonishing observers and participants with its success, the strike sparked momentum that could not be contained in a single event. Women Strike for Peace (WSP) was launched, drawing even more women into a whirlwind of action to address the threat of nuclear war and stop atmospheric nuclear tests and the attendant radioactive fallout.

After less than two years of prodigious activity, the WSP shared a significant victory when the Limited Test Ban Treaty, banning nuclear tests in the atmosphere and outer space and under water, entered into force on October 11, 1963. President John Kennedy’s science adviser, Jerome Weisner, later gave specific credit for persuading Kennedy to support the treaty “not to the arms controllers inside government” but to the WSP, along with the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE) and Linus Pauling.2

After less than two years of prodigious activity, the WSP shared a significant victory when the Limited Test Ban Treaty, banning nuclear tests in the atmosphere and outer space and under water, entered into force on October 11, 1963. President John Kennedy’s science adviser, Jerome Weisner, later gave specific credit for persuading Kennedy to support the treaty “not to the arms controllers inside government” but to the WSP, along with the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE) and Linus Pauling.2

The initial call for the strike went out after a small September 22 meeting convened by Dagmar Wilson at her Washington home. Wilson and the strike organizers were alarmed by escalating nuclear dangers and dismayed by the lack of urgent response from primarily male leaders in government and peace organizations.3 They sent the strike call via informal networks using phone trees and chain letters. This impressive low-tech organizing in less than six weeks—imagine if these women had cell phones, email, and social media—reached a receptive audience ready to act.

As Ethel Taylor, who organized the Philadelphia strike, explained,

When I received the letter from Dagmar asking me to organize a strike for peace in the Philadelphia area, I immediately went into action. Her view that radioactive fallout was an emergency, not merely an issue, expressed my feelings exactly. I called a meeting at my home and invited women.… I told them what I knew of Dagmar’s motivation for calling the strike: simply put, nuclear weapons testing was dangerous to our children’s health, and could only escalate the arms race.4

Many women and more than a few men were similarly alarmed and motivated. The moment was ripe for several reasons. The danger of nuclear war felt imminent. Throughout the 1950s, bomb shelters were built, and children routinely practiced “duck and cover” drills in school. Although some people may have been falsely reassured that these activities would protect them, everyone, including young children, knew that nuclear war was a real threat.

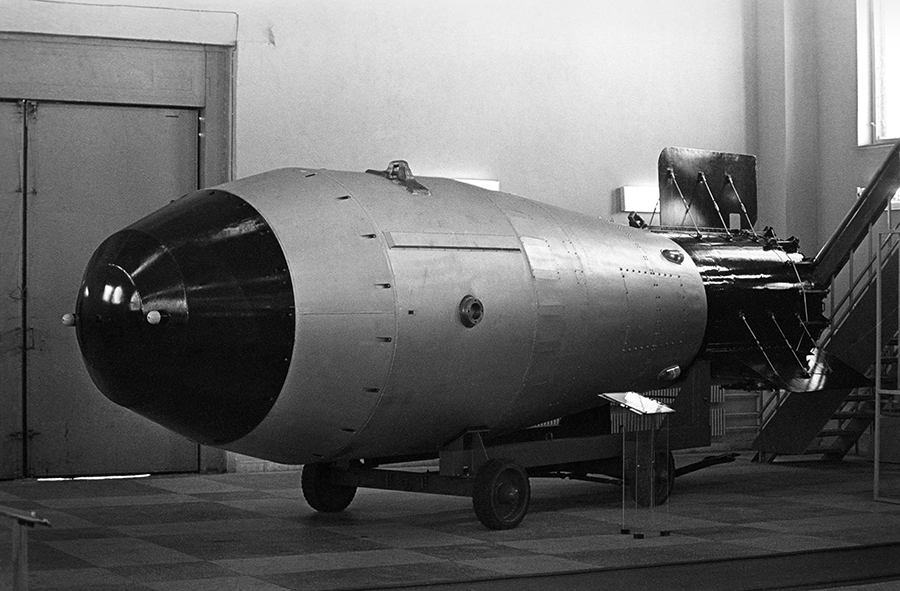

In the weeks before the organizers planned the strike, the nuclear threat grew. On August 13, 1961, the Berlin Wall went up along with U.S. and Soviet tensions. In August and September, the Soviet Union, followed by the United States, broke the testing moratorium that had been in place for almost three years. Over the next 16 months, the two countries conducted more nuclear tests than in the 16 preceding years, causing a spike in global radiation levels. On October 30, 1961, the Soviet Union conducted “Tsar Bomba,” the largest ever nuclear weapons test, with a yield of 50 megatons.5

Along with driving the arms race, atmospheric nuclear testing produced radioactive fallout, a known and alarming public health concern. In fact, some parents were so concerned that they sent their children’s baby teeth to be checked for harmful levels of strontium-90.6

Along with driving the arms race, atmospheric nuclear testing produced radioactive fallout, a known and alarming public health concern. In fact, some parents were so concerned that they sent their children’s baby teeth to be checked for harmful levels of strontium-90.6

The women who launched the WSP wanted more urgent action in response to this perilous situation. Kennedy had come into office promising an end to nuclear testing and spoke of challenging the Soviet Union to a “peace race,”7 yet he deployed more nuclear weapons, increased Pentagon spending, and resumed nuclear tests.8

Many of the women strikers were involved in key peace organizations, particularly SANE. They felt hamstrung by SANE’s hierarchal structure and by male leaders who the women perceived as “less agitated, more deliberate, and more slowly moved to action.”9 Also, SANE and other peace organizations, including Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), had been targeted by anti-communist red-baiters. This did serious damage to the organizations’ reputations, hindering their effectiveness. It was another frustration for the WSP leaders who felt compelled to leave or distance themselves from SANE and the WILPF.10

WSP leaders took deliberate steps to avoid similar red-baiting. Following the strike, they formed a “non-organization” network that had no membership dues or information that could be collected by entities such as the House Un-American Activities Committee. Also, in 1962, the WSP adopted an intentionally inclusive national policy statement decreeing that “we are women of all races creeds and political persuasions.”11

Wilson summed up the feelings driving the women to act when she wrote, “We were worried. We were indignant. We were Angry.”12 They channeled that emotional commitment into relentless bold action. This included picketing, marching, and various creative demonstrations. For example, one group rented a fallout shelter, parked it in shopping center, and converted it into a “Peace Center” from which the activists distributed educational materials and called attention to the false security promised by fallout shelters.13

There were also persistent lobby activities, or as Amy Swerdlow, WSP member and historian, described, “an uninterrupted stream of visits to congressional representatives, to public officials…and to government agencies.”14 The activism extended internationally; a delegation of 50 women went to Geneva in 1962 to make the case for a test ban at the 17-nation Committee on Disarmament.15

The harmful effects of atmospheric nuclear fallout were a particular focus of education and action with “Pure Milk Not Poison” a commonly used slogan. Concerns about milk contamination included calls for boycotts of fresh milk and instructions on how to use powdered milk as a substitute. One campaign recommended that people threaten to cancel home milk deliveries if efforts to decontaminate milk were not undertaken.16

In 1961 the strikers were predominately white, middle-class women of the early Cold War era.17 They embraced traditional motherhood activities and self-identified as “ordinary housewives.” They wore skirts, hats, and white gloves to demonstrations and brought along their children. In 1962, The New York Times reported that, “[f]or the most part, they stress femininity rather than feminism.”18 In part, this feminine, maternal image helped the women garner media coverage and enabled them to push for radical change while clothed according to the expected norms of society. Although these women started out at the nadir of feminist consciousness, they became part of the rising tide of feminism’s second wave. They were empowered by working together and by the effectiveness of their actions.

In December 1962, 14 WSP leaders were called before the House Un-American Activities Committee for hearings that marked the group’s transformative moment. In a masterful theatrical display, numerous WSP activists showed up with children in tow. They cheered the witnesses and handed them roses. The first witness, Blanche Posner, lectured the committee on the women’s maternal motivation, stating, “This movement was inspired and motivated by mothers’ love for children.… When they were putting their breakfast on the table, they saw not only the Wheaties and milk, but they also saw strontium 90 and iodine 131.… They feared for the health and life of their children.”19 The WSP effectively rebutted the committee’s charges, making the congressional accusers look foolish while empowering the women and strengthening the WSP.20

In December 1962, 14 WSP leaders were called before the House Un-American Activities Committee for hearings that marked the group’s transformative moment. In a masterful theatrical display, numerous WSP activists showed up with children in tow. They cheered the witnesses and handed them roses. The first witness, Blanche Posner, lectured the committee on the women’s maternal motivation, stating, “This movement was inspired and motivated by mothers’ love for children.… When they were putting their breakfast on the table, they saw not only the Wheaties and milk, but they also saw strontium 90 and iodine 131.… They feared for the health and life of their children.”19 The WSP effectively rebutted the committee’s charges, making the congressional accusers look foolish while empowering the women and strengthening the WSP.20

Throughout the 1960s, the WSP evolved with the times, participated in growing movements, and expanded to be what today would be called more intersectional. Key leaders joined and led the “women’s liberation,” or second wave of feminism, movement. Most prominent was Bella Abzug, the WSP national legislative leader who won a seat in Congress in 1970 and was a key voice for women’s rights and political empowerment. Coretta Scott King was also a WSP participant and was in the delegation that traveled to Geneva in 1962.

Following the 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty, the Vietnam War became the WSP’s major concern. Initiatives such as the Jeannette Rankin Peace Brigade later in the decade brought together activist strands advocating for women’s liberation, anti-racism, anti-poverty, and anti-war policies. Eventually, the WSP embraced a broader peace and human rights agenda, although for key leaders in the group, ending all nuclear testing and the nuclear arms race remained core goals.

In 1988, at a press conference marking the 25th anniversary of the Limited Test Ban Treaty, I was inspired to hear Taylor talk about her experience with the WSP and the effort to secure what she called the unfinished business of a comprehensive test ban treaty. I wondered why, even as a student of U.S.-Soviet relations and arms control, I had never heard anything about mothers who had sent their children’s teeth to be checked for strontium-90 or this huge women’s strike in 1961.

The WSP played a significant role in advocating for nuclear disarmament and in pushing forward the second wave of feminism. Sadly, this story is not told often among peace activists, feminists, or anyone else. It is a history that provides needed inspiration and proof that bold, unrelenting activism can accomplish remarkable change.

Grassroots movements ebb and flow. In recent decades, disarmament progress has continued but mostly at a slower and less momentous pace. Passionate activism has decreased, and nuclear disarmament advocacy has become more the bailiwick of a professional niche community. In the process, too much of the WSP-style sense of urgency has been lost.

Even in today’s very different environment, when atmospheric testing has ended and the threat of nuclear weapons use is not quite as imminent, we could learn from the WSP and recognize that nuclear weapons dangers are not just issues to be discussed, but emergencies that require action.

In the early 1960s, there was little question that nuclear weapons posed an existential threat. When Silent Spring was published in 1962, the harmful effects of nuclear weapons fallout described in the book were well known, although environmental harms from pesticides and other toxins were not yet understood.21 Ironically, people are now keenly aware of the harm done by environmental contaminants and climate change, but are oblivious to the health and environmental damage caused by nuclear weapons production and underground testing and to the fact that nuclear weapons use could wipe out humanity in an afternoon. To revive an old slogan, it is still true that nuclear weapons are bad for children and other living things. Those of us who know this reality should say so more clearly.

We could also take a few lessons from the first years of the WSP. That means devising a strategy with an understanding of the zeitgeist—what issues and events will get media coverage, where to find intersections on key concerns with various partners, how to build political power. There also needs to be coordinated, focused, and dogged action. Ending atmospheric nuclear testing was not the only thing women strikers wanted, but ending testing was their single most urgent goal, and it was clearly understood by most Americans.

Following the first strike, it was evident that the media and policy leaders were paying attention. By the time the bullies on the House Un-American Activities Committee came for the WSP, the women had built power and were executing their game plan. They could not be derailed as other peace organizations had been. They confidently pushed forward for the human race. Now it is our turn to pick up the pace and finish what they started.

ENDNOTES

1. Amy Swerdlow, Women Strike for Peace: Traditional Motherhood and Radical Politics in the 1960s (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), p. 247. Swerdlow, a historian and Women Strike for Peace (WSP) member who wrote its comprehensive history, notes that this number “became part of the founding legend” of the WSP based on estimates of organizers that she could not independently verify.

2. Andrew Hamilton, “MIT: March 4 Revisited Amid Political Turmoil,” Science, March 13, 1970, p. 1476.

3. Swerdlow, Women Strike for Peace, pp. 16–21, 47–48.

4. Ethel Barol Taylor, We Made a Difference (Philadelphia: Camino Books, 1998), p. 1.

5. Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization, “30 October 1961 − The Tsar Bomba,” n.d., https://www.ctbto.org/specials/testing-times/30-october-1961-the-tsar-bomba (accessed October 14, 2021); Arms Control Association, “Nuclear Testing and Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) Timeline,” July 2020, https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/NuclearTestingTimeline.

6. Jeffrey Tomich, “Decades Later, Baby Tooth Survey Legacy Lives On,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 1, 2013, https://www.stltoday.com/lifestyles/health-med-fit/health/decades-later-baby-tooth-survey-legacy-lives-on/article_c5ad9492-fd75-5aed-897f-850fbdba24ee.htm.

7. John Kennedy, “Address Before the General Assembly of the United Nations, September 25, 1961,” John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, n.d., https://www.jfklibrary.org/archives/other-resources/john-f-kennedy-speeches/united-nations-19610925 (accessed October 14, 2021).

8. “Nuclear Test Ban Treaty,” John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, n.d., https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/nuclear-test-ban-treaty (accessed October 14, 2021); John Kennedy, “Special Message to the Congress on the Defense Budget, March 28, 1961,” The American Presidency Project, n.d., https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/236195 (accessed October 14, 2021).

9. Swerdlow, Women Strike for Peace, p. 48.

10. Ibid., pp. 45–47; Taylor, We Made a Difference, pp. 5–7 (recounting frustrations with the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy in their dealing with anti-communist witch hunts and how this shaped the WSP development); Harriet Hyman Alonso, Peace as a Women’s Issue (New York: Syracuse University Press, 1993), pp. 157–192, 202 (addressing the struggles of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) and noting how the WSP was in part “born directly out of the discontent with WILPF’s hierarchical structure and anti-Communist stance”).

11. Taylor, We Made a Difference, p. 7.

14. Swerdlow, Women Strike for Peace, p. 81.

17. Elaine Tyler May, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War, 4th ed. (New York: Basic Books, 2017) (describing the context of the Cold War in the 1960s).

18. Jean Molli, “Women’s Peace Group Uses Feminine Tactics,” The New York Times, April 19, 1962, p. 26.

19. Communist Activities in the Peace Movement (Women Strike for Peace and Certain Other Groups): Hearings Before the United States House Committee on Un-American Activities, 87th Cong. 2074 (1962) (testimony of Blanche Posner).

20. Swerdlow, Women Strike for Peace, pp. 97–124; Taylor, We Made a Difference, pp. 19–21.

21. Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (Boston: First Mariner Books, 2002), pp. 6, 234. See also Mark Stoll, “Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, a Book That Changed the World,” Environment and Society Portal, July 8, 2020, https://www.environmentandsociety.org/sites/default/files/rachelcarson_silentspring_version2_1.pdf.

Kathy Crandall Robinson is the chief operating officer at the Arms Control Association. For decades, she has advocated for nuclear disarmament and related policies, working with a variety of organizations, including Women's Action for New Directions, the Alliance for Nuclear Accountability, and Women Strike for Peace.