"In my home there are few publications that we actually get hard copies of, but [Arms Control Today] is one and it's the only one my husband and I fight over who gets to read it first."

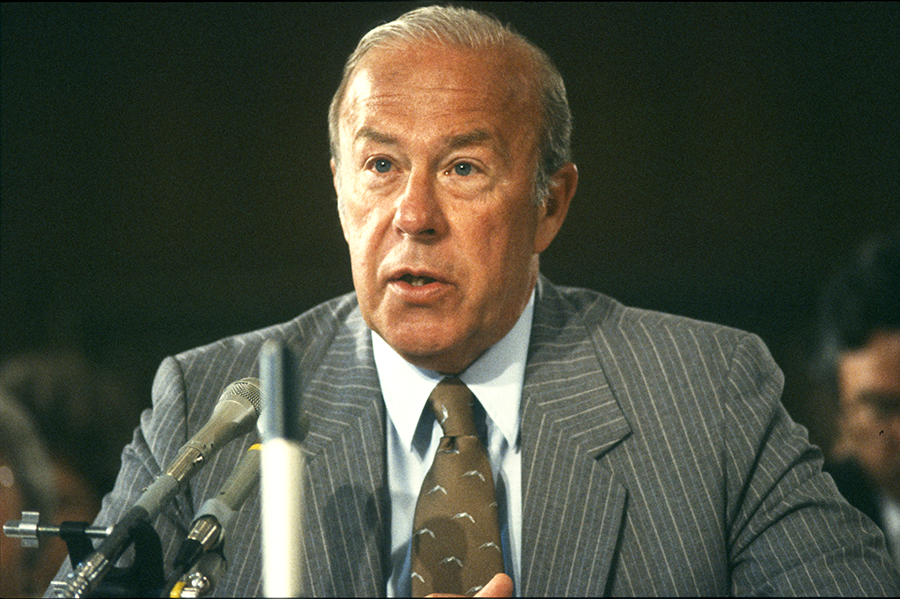

George Shultz (1920–2021) American Statesman and Nuclear Abolitionist

March 2021

By Michael Krepon

George Shultz, former Cabinet official and an ardent nuclear abolitionist, has passed away. He was 100 years old.

Shultz died on February 6 after an extraordinary life in service to his country, his causes, and his loved ones. He was a man of great moral clarity, uncommon skills, and common sense. Shultz succeeded in whatever ways he chose to apply his prodigious talents. His commitment to public service was inculcated at home by quietly purposeful parents and at Princeton University. After graduation, he joined the Marines to fight for the country in World War II.

Shultz died on February 6 after an extraordinary life in service to his country, his causes, and his loved ones. He was a man of great moral clarity, uncommon skills, and common sense. Shultz succeeded in whatever ways he chose to apply his prodigious talents. His commitment to public service was inculcated at home by quietly purposeful parents and at Princeton University. After graduation, he joined the Marines to fight for the country in World War II.

After his stint with the Marines, he received his doctorate and taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He then joined the faculty of the business school at the University of Chicago, where he became its dean. From there, President Richard Nixon recruited him to be his secretary of labor, after which he ran the Office of Management and Budget and was secretary of the treasury. In this latter capacity, he rejected the White House’s importuning to look into the tax returns of those on Nixon’s “enemies list.”

Shultz moved on to the next challenge in running Bechtel, the largest construction firm in the United States with a portfolio of immense projects overseas.

Then, in mid-1982, President Ronald Reagan picked up the phone to ask for his help at the Department of State, where Secretary Alexander Haig had quickly worn out his welcome. Reagan knew what he wanted to accomplish, but his ambitions were sometimes in conflict, and he lacked some of the skills needed to get things done. Shultz lacked none of them. He excelled in the arts of bureaucratic maneuver and negotiation. His storied poker face masked a fierce will to get meaningful things done. If Shultz was in your foxhole, you had good company.

Shultz and his éminence grise, Paul Nitze, helped steer Reagan toward his crowning achievement of abolishing Soviet and U.S. intermediate- and short-range ground-launched missiles. In so doing, they helped Reagan and his Soviet counterpart, General-Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev, break the back of the nuclear arms race and pave the way for negotiations that led to the deep, verifiable cuts in strategic forces through the 1991 and 1993 Strategic Arms Reduction Treaties.

This story of how Reagan and Gorbachev achieved the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty has been well told. What remains a mystery is how Shultz came to adopt abolitionist views. Did Reagan steer and convert Shultz, or was Shultz already converted before joining the Reagan administration? I have not been able to discover the answer.

Shultz was steaming back to San Diego after an intense tour of duty in the South Pacific in 1945 when he heard about the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the subsequent Japanese surrender. His views about nuclear weapons, however, remained largely unexpressed in public until he emerged as Reagan’s staunchest supporter for abolition.

Reagan had long held that nuclear weapons were evil, but he kept this mostly to himself. Few expected him to act on his beliefs. He was after all a staunch anti-Communist, and he had endorsed a major defense buildup, including strategic modernization programs, after a “decade of neglect” to such matters that was, if truth be told, imaginary. Reagan was intent on using the buildup to do something heroic about nuclear weapons. He was not a church-going man, but he took scripture seriously, and he was dead set against Armageddon happening on his watch.

Reagan conveyed this to Shultz over dinner on February 12, 1983, when Washington was shut down by a heavy snowfall. Shultz told me in an interview that this was when he first learned of Reagan’s staunch abolitionism. Thereafter, Shultz knew he would have the president’s backing in his intense bureaucratic warfare with Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger over nuclear arms control.

James Timbie, who worked with many secretaries of state on arms control, found Shultz to be “a sophisticated man who navigated very tricky waters.” Timbie stresses that he was also an uncommonly good listener. If you made a persuasive case, Shultz would take it in and carefully consider the pros and cons. Shultz listened to Reagan. Something must have struck a chord—perhaps it was Reagan’s moral clarity on the nuclear issue—but Shultz was not someone who turned on a dime. His friend and guide on matters of the spirit, Episcopal Bishop William Swing, knew Shultz as someone who could change his mind. After doing so, he would become a tenacious advocate.

James Timbie, who worked with many secretaries of state on arms control, found Shultz to be “a sophisticated man who navigated very tricky waters.” Timbie stresses that he was also an uncommonly good listener. If you made a persuasive case, Shultz would take it in and carefully consider the pros and cons. Shultz listened to Reagan. Something must have struck a chord—perhaps it was Reagan’s moral clarity on the nuclear issue—but Shultz was not someone who turned on a dime. His friend and guide on matters of the spirit, Episcopal Bishop William Swing, knew Shultz as someone who could change his mind. After doing so, he would become a tenacious advocate.

Shultz was methodical in his pursuits. After his snowbound dinner with Reagan, he sought small tests of trust and modest accomplishments with the Kremlin even during the annus horribilis of 1983, one of the most intense periods of the Cold War.

With the arrival of Gorbachev in 1985, Shultz was primed to serve Reagan’s pursuit of nuclear abolition, whether as a convert or from long-held belief. He sat in the room at the Hofdi House in Reykjavik with Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze when Reagan and Gorbachev traded proposals for abolition.

When details of the historic meeting became public and other Reagan officials scurried for cover afterward, Shultz remained steadfast. The Reykjavik summit led directly to the INF Treaty. Afterward, when other voices sought to call a time-out, Shultz was intent to move quickly to achieve deep cuts in strategic forces.

At this point, he acted not as a dutiful Cabinet officer following his president’s wishes, but as a problem solver focused on reducing the nuclear danger. He, like Reagan, viewed the nuclear dilemma as an unsustainable situation. They tried their best to fundamentally change it.

Shultz’s abolitionism was unwavering after he returned to California, as if he were channeling not only his own belief but also Reagan’s, who was unwell.

Shultz became an integral part of a group on the campus of Stanford University, where he joined forces with former Secretary of Defense William Perry, along with his close advisors Sidney Drell and James Goodby. Shultz and Perry constituted half of the “four horsemen,” joining with Henry Kissinger and Sam Nunn to co-author influential opinion pieces calling for bold steps toward abolition. According to Goodby, Shultz’s concern and persistent advocacy for nuclear disarmament continued into his final days.

George Shultz was Bishop Swing’s parishioner. The fervency of his belief in abolition is reflected in a “nuclear prayer” written by “Bill” Swing that he adopted as his own:

The Beginning and the End are in your hands, O Creator of the Universe. And in our hands, you have placed the fate of this planet. We, who are tested by having both creative and destructive power in our free will, turn to you in sober fear and in intoxicating hope. We ask for your guidance and to share in your imagination in our deliberations about the use of nuclear force. Help us to lift the fog of atomic darkness that hovers so pervasively over our Earth, Your Earth, so that soon all eyes may see life magnified by your pure light. Bless all of us who wait today for your Presence and who dedicate ourselves to achieve your intended peace and rightful equilibrium on Earth. In the Name of all that is holy and all that is hoped. Amen.

Michael Krepon is co-founder of the Stimson Center. His latest book, Winning and Losing the Nuclear Peace: The Rise, Demise, and Revival of Arms Control, is scheduled to be published this fall.