"I find hope in the work of long-established groups such as the Arms Control Association...[and] I find hope in younger anti-nuclear activists and the movement around the world to formally ban the bomb."

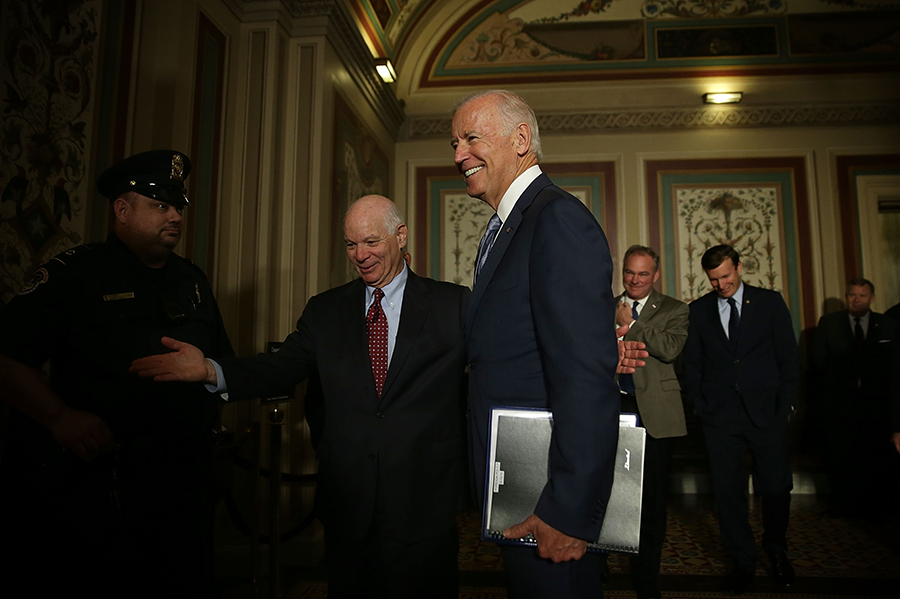

Biden Victory May Save Iran Nuclear Deal

December 2020

By Kelsey Davenport

President-elect Joe Biden’s victory in the U.S. presidential election increases the likelihood that the United States and Iran will quickly return to full compliance with the 2015 nuclear deal, but Tehran says any formal U.S. reentry into the deal will need to be negotiated.

In May 2018, President Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the agreement, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), and reimposed sanctions on Iran. (See ACT, June 2018.) Iran was abiding by the agreement’s nuclear restrictions at that time, but took steps beginning one year later to breach certain JCPOA’s limits in response to the U.S. sanctions campaign. (See ACT, June 2019.)

In May 2018, President Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the agreement, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), and reimposed sanctions on Iran. (See ACT, June 2018.) Iran was abiding by the agreement’s nuclear restrictions at that time, but took steps beginning one year later to breach certain JCPOA’s limits in response to the U.S. sanctions campaign. (See ACT, June 2019.)

Although the Trump administration claimed its maximum pressure campaign was designed to push Iran to negotiate a new deal that addressed Tehran’s nuclear program and a range of other activities, Biden has stated a clear preference for restoring the JCPOA.

In a Sept. 13 CNN commentary, Biden wrote that “[i]f Iran returns to strict compliance with the nuclear deal, the United States would rejoin the agreement as a starting point for follow-on negotiations.”

Iranian officials have rejected Trump’s push for negotiations on a new deal, but have said consistently that if Washington returns to full compliance with its obligations under the JCPOA, Iran will do likewise.

After Biden was projected the winner of the election, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani said that Iran “has always adhered to its commitments when all sides responsibly implement” their JCPOA obligations.

Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif offered more detail on the Iranian position on Nov. 17, saying that a return to full implementation by the United States and Iran can be “done automatically” and “needs no negotiations.” However, Zarif said that if the United States wants to rejoin the JCPOA, Iran will be “ready to negotiate how” Washington can reenter. U.S. reentry, however, is “not a priority,” Zarif said.

The nuclear deal does not contain any provisions detailing what, if any, steps a state must take to rejoin the deal.

Zarif’s comments appeared to imply that Iran would be satisfied in the short term with Washington and Tehran fully implementing their obligations under the JCPOA without the United States being a state party and that Iran may try to impose conditions to a formal U.S. return.

Formally rejoining the JCPOA would give the United States certain privileges, such as participating in meetings of the Joint Commission, which oversees the agreement’s implementation, and having the power under UN Security Council Resolution 2231 to unilaterally trigger a reimposition of UN sanctions on Iran in the event of a violation.

Zarif’s comment about negotiating a return to the JCPOA may be motivated in part by concern that the United States would abuse the UN snapback privilege in the future. The Trump administration attempted to snap back sanctions on Iran earlier this year, despite having withdrawn from the JCPOA, but was opposed because the United States was no longer a participant in the nuclear deal. (See ACT, November 2020.)

It appears that each Biden and Rouhani have the authority to return their respective countries to compliance with the JCPOA, but some of the details and determining the sequencing may pose challenges.

For the United States to return to full compliance with the accord, the Biden administration would need to waive sanctions reimposed when Trump withdrew from the accord and determine if any of the additional sanctions imposed on Iran since May 2018 should be waived.

Iranian officials have called for all of the sanctions put in place by Trump since May 2018 to be lifted, including those imposed for non-nuclear issues, such as support for terrorism.

Nothing in the JCPOA prohibits the United States from imposing sanctions on Iran for non-nuclear activities, but Trump administration officials have indicated that some of these sanctions were put in place to complicate any future return to the JCPOA, suggesting that some of the designations may not have been made in good faith.

Despite this, the Biden administration may face opposition from Congress if it lifts designations on individuals and entities sanctioned under executive orders designed to prevent terrorism, for example.

The Biden administration may also need to make clear that it views Security Council Resolution 2231, which endorsed the JCPOA and helps implement it, as intact. The Trump administration attempted to use a provision in Resolution 2231 to reimpose all prior UN sanctions on Tehran lifted as a result of the JCPOA in order to prevent the UN arms embargo on Iran from expiring in October. While Security Council members rejected the U.S. argument that it was entitled to snap back the UN sanctions, the Trump administration maintains that the measures were reimposed.

Rouhani appears to have support from Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei to return to compliance with the JCPOA, if the United States does likewise.

Saeed Khatizbadeh, spokesman for Iran’s Foreign Ministry, summarized Khamenei’s thinking about the future of the nuclear deal, noting that the United States must accept that it made mistakes, end its “economic warfare” against Iran, “implement [its] commitments” and then “compensate for the damages.” It is not clear what compensation Iran will seek, but the order of Khamenei’s steps and Zarif’s comments suggest that Tehran may seek compensation in the negotiations over U.S. reentry into the JCPOA, rather than as a condition for returning to compliance.

For Iran to return to compliance it will need to reverse its violations of the JCPOA. Most of the steps necessary could be accomplished quickly and must include shipping out or blending down uranium enriched in excess of the JCPOA’s limit on 300 kilograms of uranium-235 gas enriched to 3.67 percent, halting enrichment above 3.67 percent, halting enrichment at Fordow and removing all uranium from that location, and dismantling advanced centrifuges installed and operating in excess of JCPOA limits.

Former U.S. Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz told Axios on Oct. 30 that Iran could take those steps in about four months.

A potentially more challenging question is how to address new advanced centrifuges Iran installed over the past year that are not covered by the JCPOA. The JCPOA allows Iran to introduce new centrifuges with permission of the Joint Commission, the body that oversees implementation of the JCPOA, but Iran did not seek such approval.

It is unclear if the parties to the JCPOA will ask Iran to dismantle the new machines or if Iran will be permitted to test them in restricted numbers.