"The Arms Control Association’s work is an important resource to legislators and policymakers when contemplating a new policy direction or decision."

Saudi Arabia May Be Building Uranium Facility

September 2020

By Julia Masterson and Shannon Bugos

With Chinese support, Saudi Arabia may be constructing a new uranium processing facility to enhance its pursuit of nuclear technology, The Wall Street Journal reported on Aug. 4. Citing unnamed Western officials, the report said that a facility near Al Ula is intended to be used to produce concentrated uranium, known as yellowcake, from mined ore. The reported development comes as U.S. and Saudi officials have been unable to agree on the terms of a nuclear cooperation agreement to support Saudi plans to develop nuclear energy.

The Saudi Energy Ministry reportedly has categorically denied the existence of such a facility at that location. If confirmed, such a facility could signify Saudi progress toward constructing an indigenous uranium enrichment program, as yellowcake production is a key step in refining uranium for civilian or military uses.

The Saudi Energy Ministry reportedly has categorically denied the existence of such a facility at that location. If confirmed, such a facility could signify Saudi progress toward constructing an indigenous uranium enrichment program, as yellowcake production is a key step in refining uranium for civilian or military uses.

Saudi officials have stated their intent to pursue a uranium enrichment program as part of the country’s plan to build 16 civilian power reactors over the next 20 to 25 years at a cost of more than $80 billion. (See ACT, October 2019.) Companies from the United States, Russia, South Korea, China, and France are competing for a contract to build the first two of the planned 16 nuclear power reactors, but Riyadh has yet to select a vendor.

Israel also raised concerns about the new facility to the Trump administration, Axios reported on Aug. 19. There are “worrying signs about what the Saudis might be doing, but it is not exactly clear to us what's going on in this facility," said one senior Israeli intelligence official.

Saudi Arabia is not believed to have any uranium enrichment program as of now, but mastery of the enrichment process could embolden Riyadh to enrich to weapons-grade levels.

Revelation of the facility and Saudi Arabia’s possible lack of transparency has spurred renewed concern from members of Congress about how the Trump administration might address Saudi nuclear ambitions.

Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.) told Arms Control Today that “President Donald Trump’s cozying up to Saudi Arabia has threatened our national security interests and undermined our values,” referring in particular to the administration’s lack of response to the October 2018 murder in Turkey of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, a Virginia resident.

“The return on this investment is now clear: a purported ally turning to China to accelerate a nuclear arms race in the Middle East,” said Kaine.

Meanwhile, three Democratic members from the House Foreign Affairs Committee—Reps. Joaquin Castro (Texas), Ami Bera (Calif.), and Ted Deutch (Fla.)—sent a letter on Aug. 17 to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo requesting information and a briefing on the recent revelation as it “raises further questions about whether Riyadh’s nuclear program is exclusively for peaceful purposes.”

Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.) led a bipartisan group of senators in writing an Aug. 19 letter to Trump also demanding further information and a briefing on the status of U.S.-Saudi civil nuclear cooperation negotiations and the state of U.S. discussions with China on Riyadh’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs.

“Riyadh’s apparent lack of transparency regarding its nuclear efforts coupled with a growing ballistic missile program poses a serious threat to the international nonproliferation regime and United States objectives in the Middle East,” the senators wrote.

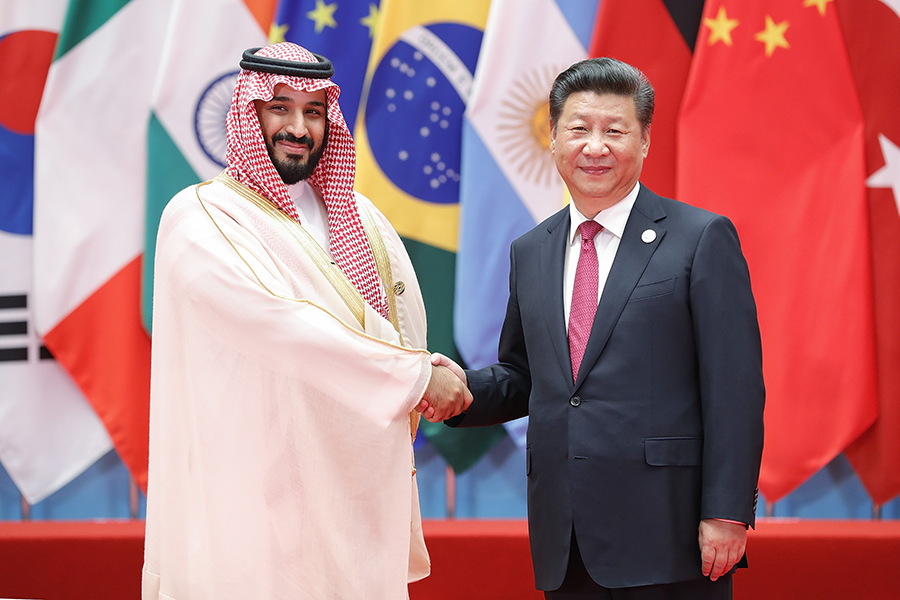

Concerns about Riyadh’s nuclear intentions have been exacerbated by rhetoric from Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman, who in 2018 pledged that “if Iran developed a nuclear bomb, we will follow suit as soon as possible.” (See ACT, June 2018.)

A U.S. intelligence analysis circulated in early August detailed a second newly constructed structure near Riyadh, according to an Aug. 5 report by The New York Times. Analysts speculated it could be an undeclared nuclear facility, but the confidence with which that assessment was made is not clear.

Reports of the existence of the site near Al Ula allege that Saudi Arabia was aided by China in its construction. Asked about China’s role in Saudi Arabia’s nuclear development, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Wang Webin said Aug. 7 that “China and Saudi Arabia are comprehensive strategic partners,” who “maintain normal energy cooperation.” He did not address the suspected yellowcake facility, but said that Beijing “will continue [its] strict fulfillment of international obligations in nonproliferation and pursue cooperation in peaceful uses of nuclear energy with other countries.” China and Saudi Arabia’s nuclear collaboration dates back to 2012, when the two countries signed their first cooperative pact.

Saudi Arabia has also received help from China on the significant expansion of its domestic ballistic missile program, according to U.S. intelligence agencies in June 2019. (See ACT, July/August 2019.)

Currently, Saudi Arabia has a comprehensive safeguards agreement in place with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) that is complemented by an outdated small quantities protocol, reflective of the negligible size of its nuclear program at the time its safeguards agreement was concluded in 2005. Under that protocol, Saudi Arabia is not obligated to invite IAEA inspectors into its nuclear facilities, including any potential yellowcake production facilities.

IAEA officials have been pushing for Saudi Arabia to transition to a full-scope comprehensive safeguards agreement for several years as Riyadh has moved to expand its civilian nuclear program. Following the revelation of the possible yellowcake facility, Iran’s permanent representative to the IAEA, Kazem Gharibabadi, urged Riyadh on Aug. 8 to strengthen its agreement with the agency and invite inspectors in.

U.S.-Saudi negotiations on the nuclear energy cooperation deal, called a 123 agreement after the section of the 1954 Atomic Energy Act requiring it, have stalled over the past year.

An April report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office suggested that U.S.-Saudi talks have faced two unresolved issues. First, Riyadh has not agreed to sign an additional protocol to its limited safeguards agreement, which would provide the IAEA with a broader range of information on its nuclear-related activities. Second, Saudi Arabia has so far declined to promise to forgo nuclear fuel production activities, a step that is called a nonproliferation “gold standard.” (See ACT, June 2020.)

A 123 agreement sets the terms and authorizes cooperation for sharing U.S. peaceful nuclear technology, equipment, and materials with other countries. A 123 agreement can include a gold standard commitment in which a cooperating country agrees to refrain from enriching uranium or reprocessing plutonium, as those activities can be used to produce weapons-grade material. By forgoing those, countries adhering to a gold standard signal their commitment to nuclear nonproliferation.

In September 2019, Energy Secretary Rick Perry reportedly sent a letter to Saudi officials stating that the United States would require Saudi Arabia to adopt an additional protocol with the IAEA and commit to the gold standard. (See ACT, October 2019.)

Kaine questioned U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Arms Control Marshall Billingslea during his July 21 hearing for the top arms control job at the State Department on whether he would maintain that requirement. The State Department leads negotiations on 123 agreements, which, once complete, require congressional approval.

“You have my commitment that I will pursue the so-called gold standard in these 123 agreements,” said Billingslea. “I believe [it] should also be pursued with the Saudis.” He did not address the additional protocol.