Nuclear Security Summits: A History

September 2020

Learning Lessons From the Nuclear Security Summit Process

Nuclear Security Summits: A History

By Amandeep S. Gill

Palgrave Macmillan, 2020, 293 pp

Reviewed by Manpreet Sethi

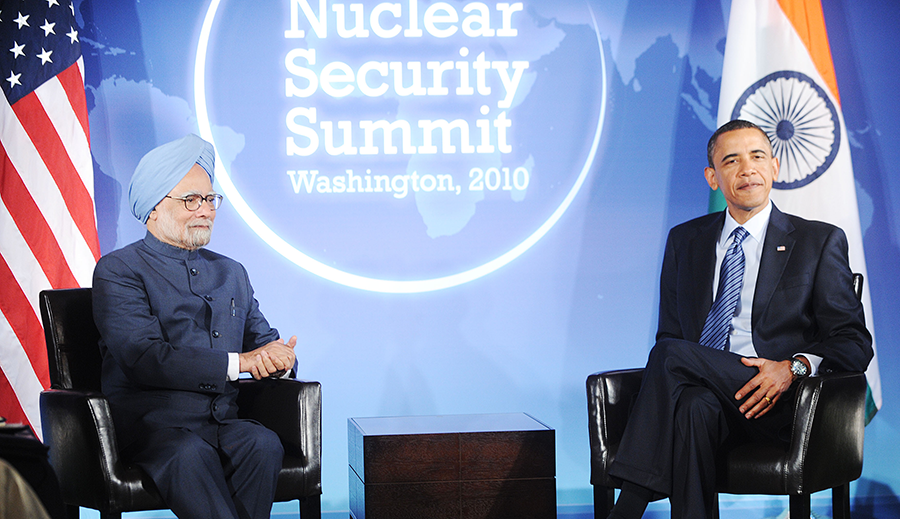

During his eight years in office, U.S. President Barack Obama maintained a sharp focus on the issue of nuclear security. He clearly identified nuclear terrorism as the most important challenge for the United States and placed it above the nuclear-weapon risks posed by China and Russia. Given his risk assessment, it is not surprising that he put his personal weight behind the creation of a new multilateral mechanism to address the threat. Thus, the nuclear security summit process was established, and Washington hosted the first summit in 2010 during Obama’s first year as president.

The summit process emerged in a particular geopolitical context in which great power relations allowed it the space to collectively address a difficult global challenge. It was also fortuitous that the national leaders of the moment enjoyed a certain cordiality in their mutual relations. For such efforts to succeed, a convergence of views between major stakeholders is necessary.

The United States and the Soviet Union showed such a confluence on the issue of horizontal nonproliferation in the 1960s, facilitating the birth of the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). Similarly, when U.S. and Russian threat perceptions converged on nuclear terrorism between 2010 and 2015, it contributed to the success of the summit process. By 2016, however, as U.S.-Russian relations soured Moscow refused to participate in the final summit, and the process concluded with the end of Obama’s second term.

A recent book by Amandeep Singh Gill tells the summit process story as the four summits were convened in The Hague, Seoul, and twice in Washington. The book, however, does not merely document the achievements of the summits, nor does it confine itself to enumerating the actions taken by participating nations. Rather, the treatise is far more academic and analytical as Gill uses the lens of nuclear learning to explain the evolution and achievements of these high-level meetings.

As an experienced diplomat, scholar, and an international civil servant, Gill provides a unique insight into the summits, thanks particularly to his work as a “sherpa” for India, taking the point in managing the nation’s participation in the summits. His book is further strengthened by its collection of annexes that include key documents, such as accounts of sherpa meetings, chairmen’s summaries of such meetings, and nonpapers presented by different countries. All will serve well as a useful primary source of information for readers.

Initially, the summit process was narrowly conceived to address the risk of nuclear terrorism by persuading nations to secure vulnerable nuclear material in a period of four years. The idea was “to force the pace of change in the area of nuclear security by bringing international peer pressure and a whole-of-government approach to preventing nuclear terrorism,” Gill writes. During the process, however, other urgent issues emerged. For instance, the 2011 nuclear accident in Japan led the second summit to address the interface between nuclear safety and security. Subsequently, the agendas of the next two summits were expanded to embrace radiological material and orphan sources, as well as the cybersecurity of nuclear plants and facilities.

Initially, the summit process was narrowly conceived to address the risk of nuclear terrorism by persuading nations to secure vulnerable nuclear material in a period of four years. The idea was “to force the pace of change in the area of nuclear security by bringing international peer pressure and a whole-of-government approach to preventing nuclear terrorism,” Gill writes. During the process, however, other urgent issues emerged. For instance, the 2011 nuclear accident in Japan led the second summit to address the interface between nuclear safety and security. Subsequently, the agendas of the next two summits were expanded to embrace radiological material and orphan sources, as well as the cybersecurity of nuclear plants and facilities.

Despite this expansion of topics, the overall focus of the summits remained narrowly framed around the sole issue of security of civilian nuclear material and facilities. Washington did not allow nuclear nonproliferation or disarmament issues to spill into the restricted frame. This ensured the success of the summit process. Also useful was the flexibility of the format of the summits, which allowed for including emerging issues and accommodation of new members. In this aspect, the summit process stands out in stark contrast to an instrument such as the NPT, which is frozen in time and has not shown the malleability to adjust to the geopolitical or technological changes that have taken place over the 50 years since it came into being.

Providing key background, Gill maps the progression of the idea of nuclear security from 1945 to 2006. He devotes a chapter each to the description and evaluation of the four summits in which he also provides a tabular description of nuclear learning, or what was not learned, against four parameters: abandonment of position, policy compromise or adjustment, development of new ideas and shared understanding, and the putting into practice of policy compromises. This effectively captures and compares the highlights of the four summits to trace the path of nuclear learning throughout the process. By the fourth summit, interactions between national knowledge makers had evolved, and it was decided to preserve a core group at the official level in the form of the Nuclear Security Contact Group that would keep the learning alive and quickly enable a future summit if necessary.

Among the many innovations that the summit process tested, three particularly stand out. The first of these is the utilization of sherpas, or national representatives who were involved in the summit preparation process. Sherpa teams included experts from various disciplines who ensured a whole-of-government approach. Their informality, flat hierarchy, and interdisciplinary nature was conducive to resolving contentious issues and enabling learning. The second unique dimension was the idea of bringing “house gifts” by individual nations or “gift baskets” by a group of nations to the summit. Summit process participants used the summits to announce their tangible nuclear security accomplishments, such as removing dangerous materials from unused facilities or establishing more rigorous border controls. This was a “valuable tool in pushing the learning envelope: the pressure generated by the expectation of what to bring to the table at the next summit accelerated learning,” Gill says. Third, the heads of governments had a huge dose of learning from a scenario-based exercise played out at the third summit when they had to think through policy responses to the simulated loss of a radioactive device. The book thus highlights some important lessons that can be drawn from the design and working of the summit process.

The momentum built around nuclear security, as well as the nuclear learning achieved through the summit process, should not be allowed to go to waste. Since the fourth summit, the Nuclear Security Contact Group and the International Atomic Energy Agency have been engaged in the implementation of national and international action plans. The Trump administration has continued active U.S. participation in the contact group, but the issue does not appear to have figured among the top U.S. priorities. Christopher Ford, U.S. assistant secretary of state for international security and nonproliferation, expressed a goal in 2017 that nuclear security tasks “become regularized, routinized, and systematized,” but this has yet to happen. The danger of nuclear terrorism has not gone away. It must be recognized that nuclear security is a journey, not a destination, or in Gill’s words, an “enduring mission.”

Meanwhile, besides nuclear security-specific learning gained through the summit process, a much wider understanding has also been achieved on what enables the successful functioning of multilateral forums. For instance, Gill points out how the summits served as “vehicles for propulsion and population of ideas, which mutate as they are contested, reframed, and adopted.” This could serve as a valuable lesson at a time when trust deficits bedevil major nuclear power relations and adjustments and compromise of ideas will be necessary as and when similar such exercises are attempted in multilateral settings.

The issue of nuclear risk reduction is one subject that would benefit from the summit process. Given that nuclear risks, particularly those related to inadvertent use of nuclear weapons due to misperceptions or miscalculations, are rapidly on the rise, the time could be ripe for major nuclear powers to initiate a summit process that brings together political leaders to evolve a shared sense of risks and measures to address them. Just as the summit process drew attention to the challenge of nuclear terrorism, a nuclear risk reduction summit could help address nuclear use risks and thus contribute to international security and global stability. Gill makes clear that the experience and knowledge of the summit process will make it easy to refresh nuclear learning whenever the need arises.

Manpreet Sethi is a distinguished fellow and head of the Nuclear Security Project at the Centre for Air Power Studies in New Delhi.