"Though we have achieved progress, our work is not over. That is why I support the mission of the Arms Control Association. It is, quite simply, the most effective and important organization working in the field today."

Translating Goals Into Agreements: An Interview with Pavel Palazhchenko

July/August 2019

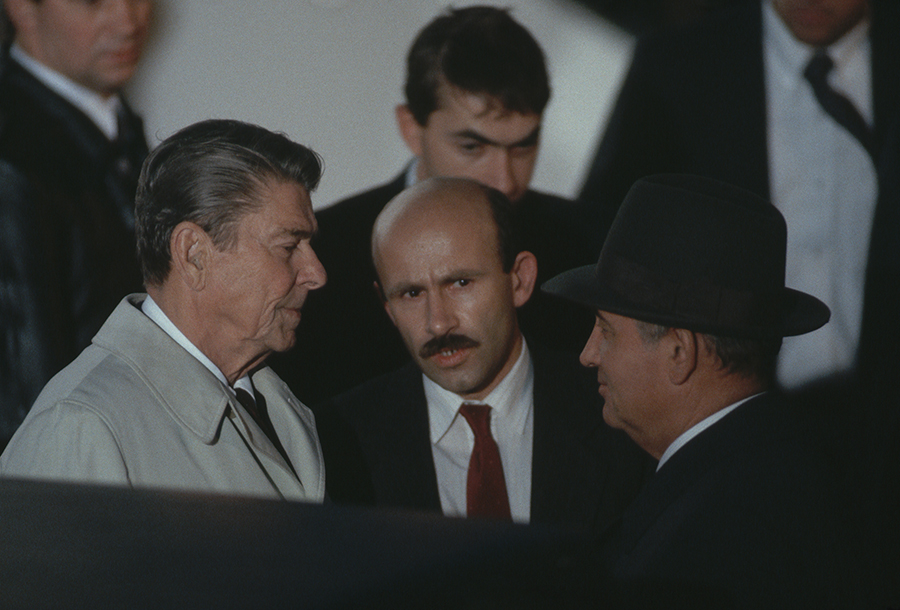

Pavel Palazhchenko has witnessed historic arms control efforts from a unique position: the interpreter’s seat next to top Soviet leaders as they negotiated the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. In the arms control community, he is instantly recognizable because of his consistent presence in images of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev meeting with U.S. President Ronald Reagan during the 1980s. Palazhchenko’s experience offers an unusual perspective on the process of arms control negotiations and the value of U.S.-Russian engagement today. He spoke with Arms Control Today on June 8 by phone from Moscow.

Arms Control Today: How did you get your start as an interpreter for the Soviet Foreign Ministry?

Pavel Palazhchenko: I graduated from what is now called Moscow Linguistic University, which at that time was called Moscow Institute of Foreign Languages, where I majored in English and French. I then studied for a year at the UN language training course in Moscow, which trained simultaneous interpreters for the UN Secretariat.

Then I worked in New York at the United Nations from 1974 to 1979, and when I returned to Moscow, I was kind of lucky because at that time they were expanding the linguistic services of the Soviet Foreign Ministry. So, there were vacancies, and I was accepted to work there. Interestingly, one of my first assignments was to work at the [Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty] negotiations that started in 1981.

Then I worked in New York at the United Nations from 1974 to 1979, and when I returned to Moscow, I was kind of lucky because at that time they were expanding the linguistic services of the Soviet Foreign Ministry. So, there were vacancies, and I was accepted to work there. Interestingly, one of my first assignments was to work at the [Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty] negotiations that started in 1981.

Those first INF Treaty negotiations, which were not successful, lasted for a little more than two years, and I basically did the entire process from beginning to end. There were several rounds of negotiations. Ultimately they were not successful, but they were still useful because it was a discussion of the conceptual basis of intermediate-range nuclear forces, the balance of arsenals on both sides, the format of a future agreement, all of those things. Of course, it was quite a bit frustrating.

The Soviet side was led by Yuli Kvitsinsky, at that time a rising star in the Soviet Foreign Ministry. On the American side, it was Paul Nitze, who was a veteran. They were two very different individuals, but they were able to work together quite well. They respected each other, and they really wanted some kind of an agreement, but politically of course, it turned out that that was not possible.

ACT: Did Soviet interpreters, and now Russian ones, receive diplomatic training and education and status? In the United States, interpreters are selected for their linguistic skills. Is it the same in Russia?

PP: We are also chosen as linguists, but in the Soviet Foreign Ministry, once you start working as a linguist, you also are a diplomat. There is no separation between different categories. You are a diplomat, and you are supposed to have that diplomatic awareness. I suspect that even though in the United States it’s kind of two separate categories, it’s still the same: you really need certain diplomatic skills. Above all, you have to be very much aware of the subject matter of negotiations. You have to have access, sometimes limited, but very often quite wide-ranging access to the diplomatic material. So even though it’s a little different in the U.S. tradition and the Russian tradition, I suspect that it’s basically quite similar.

ACT: What are the professional norms of the interpreter? Are you expected to sit and translate, or are your opinions sought?

PP: The opinions would not normally be sought because the status of the interpreter is different from the status of official members and advisers in the delegation. But of course, later when I was working with [Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard] Shevardnadze and with [Soviet leader Mikhail] Gorbachev, informally, yes, they might seek your opinion. In the arms control delegations, perhaps not so much. But you know, a delegation is a kind of environment in which you socialize, you communicate, you interact with diplomats, so you learn a lot, even though your official status is not the same as the status of the members of the delegation.

The actual work of the interpreter, specifically in arms control negotiations, is that you interpret the official statements that are delivered during the meetings of the delegations. Also, the delegation heads then talk separately, and I was interpreting their discussions. Then at the lower level, the senior military representatives talk, advisers from the foreign ministry and from the defense department talk, and there are interpreters who take care of that.

Then a couple of days later, we would exchange official translations of the formal statements that had been made at the meeting of the delegations. That is done to make sure that the terminology is correct, that we interpret the terms and understand the terms in a similar way, and that was of course useful.

The rest of it is quite informal, and to some extent, it depends on the rapport and the informal interactions within the delegations. There are official receptions where everything is quite informal and the value of what is being said is less than what is being said during the formal meetings. A lot of the talk and discussion is exploratory. It is something that can later be denied, or you can back out of some of those things, and interpreters are also involved in that type of discussion as well.

ACT: There are reports that U.S. President Donald Trump had a one-on-one meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin at their Helsinki summit in 2018, where only interpreters were present, and Trump asked his interpreter not to share or discuss the meeting with anyone in the U.S. delegation. In your experience, what are the normal standards for an interpreter in record-keeping and in sharing information with their delegation?

PP: There can be no standards to apply here because it’s a matter of government service in this case. Of course, interpreters do have a standard of confidentiality. You are not supposed to talk out of school. Whenever the president, or whoever else is the main interlocutor in a negotiation, says that something is not to be revealed to others, I would assume that’s an order, that’s something that interpreters have to obey.

ACT: You are well known, you have a higher profile than most interpreters

have achieved.

PP: That began in 1985, and it began with the first meeting that Shevardnadze had with [U.S. Secretary of State] George Shultz. That was the first formal, official meeting of foreign ministers where simultaneous interpretation was used. That is to say not the consecutive interpretation where a person speaks and then you interpret what he has said, but simultaneous interpretation with the proper equipment, microphones, and headphones. The U.S. side actually proposed this, and after some initial hesitation, this was accepted. I was asked to interpret at that meeting because I had had a lot of previous experience in doing it at the UN and elsewhere.

That was a bit of luck. I was fortunate that I was asked to do it. Then I continued both with Shevardnadze and Gorbachev. I interpreted Shevardnadze’s first meeting with President Ronald Reagan at the White House in September 1985, so the profile was high because at that time it was quite unusual. It was after a period of deep freeze in U.S.-Soviet relations, so there was a lot of media interest, so I guess that’s the reason.

That was a bit of luck. I was fortunate that I was asked to do it. Then I continued both with Shevardnadze and Gorbachev. I interpreted Shevardnadze’s first meeting with President Ronald Reagan at the White House in September 1985, so the profile was high because at that time it was quite unusual. It was after a period of deep freeze in U.S.-Soviet relations, so there was a lot of media interest, so I guess that’s the reason.

ACT: You wrote a book about your experience. Given this principle of confidentiality, was it difficult to get the book cleared by Russian officials?

PP: I was not asked to submit it for review because everyone assumes, at least in Russia I guess, that a person who had access to truly confidential information would not reveal something that remains confidential. When I was writing the book, a lot of the material from those conversations and negotiations had been declassified either on one side or both sides. Today, the memorandums of conversation from those negotiations have been made public on both sides; and even then, when I was writing the book and particularly when the book was published, a lot had already been declassified. Of course, there were certain things that were still confidential and perhaps some things that still are, but it is assumed that people that had access to those things are responsible individuals and that they will not reveal anything that will cause problems.

ACT: Looking back at the INF Treaty talks, can you describe how the negotiators from both sides worked together?

PP: The completion of the INF Treaty was the result of agreements that were achieved at the summit level. It was in Reykjavik that Gorbachev and Reagan agreed on a zero-option agreement in Europe with a limited number of INF Treaty missiles elsewhere. Ultimately, for reasons that were good and legitimate, they decided that it would be best to have a global zero. That agreement was reached, I think, in February 1987.

That was the difference. Once there is an agreement at the summit level, it’s a lot easier for diplomats to work out the details. Whereas during the first negotiations, the unsuccessful negotiations of 1981 to 1983, there was no common basis agreed at the highest level for negotiating the details and actually drafting the treaty.

ACT: You referred to a deep freeze in U.S.-Soviet relations in the 1980s, and we may be in a similar period now, with the two countries struggling to talk to each other, including about the INF Treaty. Are there parallels between what you saw firsthand to what could happen today?

PP: The main lesson is simple: If there is dialogue, then there is a chance that some kind of an agreement will be achieved. If there is no dialogue, then there is no chance that an agreement will be achieved. That’s why when the dialogue resumed between the leaders of the Soviet Union and the United States in November 1985 in Geneva—and when they established a process of discussions about all issues, the so-called four-part agenda to discuss arms control and security, regional issues, bilateral relations, and human rights—once that started, the chance for an agreement emerged.

Unfortunately, today’s leaders of Russia and the United States have not established such a process. It’s not guaranteed that a process of dialogue and negotiations will actually bring success, but at least there is a chance.

Right now, our leaders have had only one proper meeting in Helsinki. It didn’t go well. They have not had a real summit since then, and even worse, there is no diplomatic process, which to me is really a mystery why that is so. A normal process of diplomatic discussion probably would not cause political problems for either Trump or Putin, so why they have not established that kind of process, I really cannot understand. So, that may be something that they might finally want to achieve, to establish.

ACT: Perhaps when tensions are high, that is the time to talk?

PP: Well, if you look at the history of U.S.-Soviet and U.S.-Russian relations, unfortunately that is not the case. It is often when tensions start that the process of negotiations stalls or is interrupted or is even abandoned. That was the case, unfortunately, after the U-2 episode between [Soviet Premier Nikita] Khrushchev and [U.S. President Dwight] Eisenhower. That was the case after the entry of Soviet troops in Afghanistan. That is often when negotiations stall, and that’s unfortunate.

To the great credit of Gorbachev and Reagan, they never interrupted the negotiating process even though there were bumps on the road, unfortunate incidents, spy scandals, and expulsions of diplomats. Nevertheless, they persevered, and they continued the talks.

ACT: Former President Gorbachev continues to promote dialogue and arms control. Is he heard in the Russian government?

PP: I have not heard the president or the foreign minister of Russia ever quoting Gorbachev, but sometimes it seems to me they do listen.

ACT: Right now, there’s a very popular television show about Chernobyl. Did the accident at Chernobyl affect Soviet thinking about nuclear weapons issues? Did that affect any negotiations?

PP: Gorbachev has said on many occasions that the disaster at Chernobyl reinforced his view that the arsenals of nuclear weapons should be cut to a minimum, that a nuclear war is unthinkable, that it must never be fought. It strengthened his intention and his desire to work hard on some kind of agreement that would start the process of nuclear disarmament. He has stated that on a number of occasions, both when he was president and afterward.

ACT: Can the INF Treaty experience still contribute to the future?

PP: First of all, it’s very unfortunate that the United States decided to withdraw from the INF Treaty. The treaty was a great achievement. We lived in a better and safer world for over 30 years as a result of the INF Treaty. I believe that the philosophy and the legacy of that treaty need to be preserved, even though both sides have now decided to withdraw from that treaty.

Nevertheless, I think there is a good chance that an arms race, an intermediate-range nuclear forces arms race, can be avoided because I do not see any great appetite in European countries to deploy those weapons. I don’t know much about Asia, but I’m not sure that there is appetite there either.

The philosophy of the INF Treaty is that ground-based missiles of that range are dangerous because they could trigger an all-out nuclear war. That philosophy was right. The legacy of the treaty remains in the minds of many experts, in the minds of many members of the military. I believe it’s very much alive in Europe, which remains, I think, the place where we should really focus on security issues.

We are currently at a difficult crossroads, but I still think that there is a chance to preserve both the philosophy and the legacy of the INF Treaty. That’s the connection that I see between that time and now.