"I greatly appreciate your very swift response, and your organization's work in general. It's a terrific source of authoritative information."

Seeing Red in Trump’s Iran Strategy

July/August 2019

By Eric Brewer and Richard Nephew

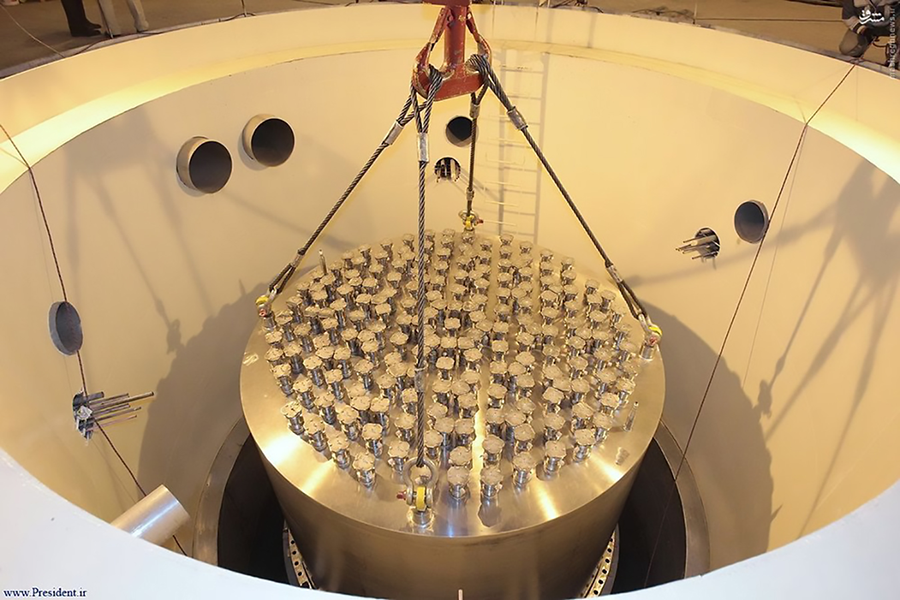

Since Iran’s May 2019 announcement that it would no longer abide by some nuclear restrictions under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the Trump administration has sought to push back against these moves by citing the imperative of the JCPOA’s constraints. The JCPOA created limits on Iran’s nuclear fuel cycle that mean Tehran would need a year to produce enough nuclear material for a bomb, and the agreement established enhanced transparency and inspector access throughout the entire fuel cycle.

The U.S. push for Iran to adhere to the deal’s terms has drawn some international incredulity given how the United States withdrew from agreement in May 2018 while noisily alleging many JCPOA flaws. More subtly, the Trump administration has begun to lay the groundwork for what can be described as its first real redline for the nuclear program: that any reduction in Iran’s one-year breakout timeline, the amount of time Iran would need to produce enough enriched uranium for a bomb, is unacceptable.

The U.S. push for Iran to adhere to the deal’s terms has drawn some international incredulity given how the United States withdrew from agreement in May 2018 while noisily alleging many JCPOA flaws. More subtly, the Trump administration has begun to lay the groundwork for what can be described as its first real redline for the nuclear program: that any reduction in Iran’s one-year breakout timeline, the amount of time Iran would need to produce enough enriched uranium for a bomb, is unacceptable.

It is unclear how much reduction the administration would tolerate, what its response would be, and given President Donald Trump’s avowed preference for a deal and to avoid another conflict in the Middle East, whether it would be enforced at all. Yet, National Security Advisor John Bolton in late May linked any Iranian expansion of enrichment activities to a deliberate attempt to shorten the breakout time to produce nuclear weapons, which would suggest that a severe response, perhaps even military force, would be on the table to prevent Iran from a nuclear restart. At the very least, the United States is shifting the traditional definition of what is unacceptable from a weapon or having the ability to produce one quickly to any deviation from JCPOA baseline restrictions.

A renewed nuclear crisis with Iran is now likely. Not only would Iran’s announced steps from May shorten the breakout timeline, only modestly at the start, but Iran has set a deadline that expires in early July for the restart of other nuclear activities that might reduce the timeline considerably faster.

Nevertheless, Iran’s nuclear actions so far do not merit this redline or the military response that could follow, nor do they rise to the level of an unacceptable threat to the United States or its interests. Rather, they are a signal that, although some in the Trump administration believe otherwise, Iran will not consent to being pushed via sanctions without seeking leverage of its own.

To be fair to the Trump administration, there is some utility in setting out a clear marker for Iran as to what constitutes unacceptable nuclear behavior. In fact, one of the biggest concerns over Trump’s Iran policy thus far is that the Iranians have seen little clarity from the White House as to what the United States wants from Iran. U.S. objectives have varied over time and, depending on who is articulating the policy, have involved everything from regime change to a renegotiated JCPOA. It would be valuable to give Iran and the rest of the world a clearer sense of U.S. intentions, expectations, and the seriousness with which the United States would treat certain Iranian nuclear actions. A firm stance now could also potentially head off a more dangerous situation down the road, and for the Trump administration, there is a palpable desire to avoid being identified as the cause of this new nuclear crisis.

Despite these potential benefits, the particular redline that appears to be in the process of being established is profoundly unnecessary, unwise, and dangerous for four reasons.

Iran’s Restart Will Be Gradual

First, establishing the one-year breakout timeline as a redline makes little sense in terms of the nuclear program itself. The JCPOA was designed to give governments at least a year to mount a strategy to react if Iran started to exit its obligations and dash to a weapon. For this reason, the JCPOA built in restrictions on Iran’s centrifuges, its uranium stockpile, and spare parts and materials for the program, as well as intrusive transparency steps that ensure the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the international community would quickly become aware of any deviation from Iran’s agreed steps.

Iran has said it will expand its enrichment of low-enriched uranium (LEU) and heavy water and will consider additional steps as well, perhaps as soon as July 6. Iran’s decision to restart these nuclear activities will eventually erode the breakout time barrier of a year, but this will occur, at least at the start, relatively slowly and incrementally. The reasons are political and technical. Politically, Iran’s main goal is to regain negotiating leverage and force Europe to provide economic benefits or risk the deal falling apart, not to race to a bomb. As Iran has done in the past, it will likely calibrate the pace and scope of its nuclear activities based in part on how the international community responds.

From a technical standpoint, Iran’s enriched-uranium stockpile will probably expand gradually. Iran has said it will exceed the JCPOA’s 300-kilogram limit by June 27, which IAEA reporting suggests would be a major increase in the pace of enrichment operations but not impossible. That said, even at the rate of enrichment that this would suggest, as much as 30 to 50 kilograms per month, it would take many months before Iran would have enough LEU, which would need further enrichment, for a bomb. Of course, enriching uranium further from its current level would be noticed by the IAEA and time consuming.

Iran’s buildup of heavy water is less concerning from a nuclear weapons perspective. Even if Iran fulfills its threat to abandon its JCPOA-mandated requirement to redesign the Arak reactor to produce less plutonium in July, the path to actually completing and starting its old reactor design would be a long and uncertain one.

More worrying would be if Iran acts on its threat to increase enrichment levels as early as July. Depending on how high Iran goes, such as resuming enrichment to near 20 percent uranium-235, this could have a seriously adverse affect on Iran’s breakout timeline as this material accumulates. A U.S. decision to end sanctions waivers that allow Iran to import 20 percent-enriched fuel for its research reactor would make

More worrying would be if Iran acts on its threat to increase enrichment levels as early as July. Depending on how high Iran goes, such as resuming enrichment to near 20 percent uranium-235, this could have a seriously adverse affect on Iran’s breakout timeline as this material accumulates. A U.S. decision to end sanctions waivers that allow Iran to import 20 percent-enriched fuel for its research reactor would make

it easy for Tehran publicly to justify higher enrichment.

Some of these steps are more concerning than others, but none would indicate a breakout, and they do not suggest that the world is facing an imminent Iranian nuclear weapons threat. Indeed, unless Iran starts to curb IAEA access, which in and of itself would be a major concern, all of these measures will be done in full view of inspectors, which is exactly how Iran wants it. There is time to resolve the crisis diplomatically before using military force. A year was judged to be a reasonable but not necessarily minimum amount of time to do so. Indeed, prior to the JCPOA, Iran only needed a few months to produce a bomb’s worth of material. Even then, the United States determined that it could stop an Iranian breakout with the use of force if necessary.

An Ambiguous Redline

Second, for this redline to work, Iran would have to know when it is nearing that threshold so that if it wants, it can refrain from doing so. Because Iran possessed a large LEU stockpile, not to mention its near 20 percent-enriched uranium, for many years prior to the JCPOA, Iran may not perceive its renewed possession of this material as now representing a casus belli for Washington. In fact, Israel even set a redline for Iran’s enrichment program that could be interpreted to permit up to 200 kilograms of near 20 percent-enriched uranium, suggesting that what Iran is presently doing is far below the Israeli threshold for action.

Moreover, breakout timelines are based on a range of assumptions, and even among U.S. allies, there was some ambiguity about those timelines as the JCPOA was negotiated. It is therefore unlikely that Iran and the United States would have a common definition of where that tipping point occurs. This presents a high risk of miscalculation.

Advocates of Trump’s redline approach may believe that this works to the U.S. advantage: by laying out extreme positions, Iran can be deterred from undertaking any nuclear expansion. This view, however, ignores two facts. First, Iran will judge what is tolerable to the West based on past experience, and higher levels and amounts of uranium may not be seen as such. Second, Iran’s perspectives on U.S. deterrence are informed by the full range of U.S. responses to Iranian behavior. With North Korea and Iran, Trump has a history of issuing grand yet vague threats and then not following through on them, a practice that is likely to undermine U.S. credibility on this redline. In addition, Trump’s own attempt to walk back his administration’s hawkish stance toward Iran in late April and early May with respect to the deployment of U.S. forces in the Persian Gulf has likely confused the Iranians. Offers to restart negotiations on a more limited slate of issues than U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s “12 demands”—a list he laid out in May 2018 for Iran to fulfill, including elimination of its nuclear fuel cycle, severe restrictions on its missile program, and the end of its relationships with Hezbollah and other proxies—probably have done likewise. It certainly has led Iran to try to convince Trump that he is being manipulated into conflict via the “B team,” a term Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif has used to describe those he says are war advocates, including Bolton, Emirati Crown Prince Mohammad bin Zayad, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman, and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Even in the likely event that this ploy fails, the dynamic means that Iran is unsure as to where the president stands in all of this. In such an atmosphere of confusion and ambiguity, dangerous mistakes can be made by both sides.

Fewer Peaceful Options

Of course, Trump administration officials and their advocates may stress that no one has mentioned the word “force” in any official capacity and that this is a conclusion being inappropriately drawn. Yet, the third problem with the redline approach being articulated is that Trump administration actions have reduced the scope of nonmilitary responses. Most options short of war have already been expended by this administration and arguably are why this predicament exists in the first place. This includes walking out of the JCPOA and reimposing and expanding sanctions.

Some additional sanctions could be imposed against Iran. Recent actions, such as designations of Iranian petrochemical companies and sectoral sanctions targeting other activities, such as Iran’s metal sector, may help U.S. sanctioners build momentum against Iran. Their value as a deterrent to Iran increasing its nuclear activities, however, is limited because the administration is already aggressively seeking to eliminate Iranian oil exports and has implemented widespread financial sanctions, which are far more damaging measures. If history is a guide, more pressure will likely cause Iran to accelerate its program if there is no realistic diplomatic off-ramp. At this point, Iran’s apparent calculus is that there is little more that Washington can do to punish Tehran from pushing back against the United States by rolling back its JCPOA commitments, at least in part and in stages. Iran sees very little difference between the sanctions pressure Washington is applying now and what more it could generate if Iran builds up its nuclear program. Without this perception, Iran would not have broken a year’s worth of restraint to act now.

The absence of specific and discrete response options for enforcing the redline runs the risk of creating a hollow commitment on the part of the United States. As the United States has learned to its chagrin in recent years, unenforced redlines carry risks and consequences. In this case, it would make it more difficult for the United States to deter Iranian nuclear threats that really do matter in the future. The United States would be ill advised to issue such pronouncements and fail to make good on the promises inherent within them. This is why setting appropriate, sober, and well-considered redlines, if redlines are set at all, is so imperative.

A Bigger Risk Ignored

Finally, although what Iran is doing to retaliate for the U.S. pressure campaign may ultimately create some breakout risk, a redline focused on protecting a one-year breakout timeline focuses on the wrong part of the problem. Iran’s most plausible and likely weapons development scenario would involve a covert program rather than relying exclusively on its known facilities and materials. Iran knows that IAEA oversight, enhanced by the JCPOA, enables rapid detection of any major steps toward breakout. Even if Iran is able to erode breakout time to the two-to-three-month range that predates the JCPOA, this is still sufficient time for the United States to detect and respond militarily, and Iran knows it.

For these reasons, the most important step the United States can take to prevent moves toward a nuclear weapon using the very facilities and materials about which Bolton is now concerned would be to ensure the transparency and monitoring of Iran’s nuclear program that the JCPOA provides. These same transparency and monitoring tools that help detect a breakout can give confidence that Iran is not presently in possession of covert facilities and that they would be detected long before they can deliver a nuclear weapon.

A Better Approach

The United States does need to demonstrate its readiness to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons. For this reason, showing a willingness to use all the means of U.S. power, including diplomacy, to prevent such an eventuality is reasonable and prudent. Indeed, diplomacy is the only means that the United States has employed in the last two decades that has proven capable of limiting Iran’s nuclear program to a significant degree and for a sustained period of time.

Trump has repeatedly said that he wants a better deal than the JCPOA. It is an ambition that people across the political spectrum can endorse, but it seems unlikely that a significantly better deal is available in the current climate. A better deal will not come from issuing ill-founded redlines that increase the risk of miscalculation while targeting the wrong threats. Rather, the Trump administration should invest itself in developing a realistic negotiating agenda and getting back to the table with Iran to avoid this crisis while it still can.

Eric Brewer is a fellow and deputy director of the Project on Nuclear Issues with the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. He served a decade in the U.S. intelligence community, including as deputy national intelligence officer for weapons of mass destruction with the National Intelligence Council. Richard Nephew is a senior research scholar with the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University. He has held positions at the Department of Energy and Department of State and on the National Security Council.