An Uncertain Future for North Korean Talks

April 2019

By Kelsey Davenport

North Korean leader Kim Jong Un may be losing interest in diplomacy with the United States, according to officials in Pyongyang, creating uncertainty around the future of U.S.-North Korean negotiations. If the two sides do resume talks, diplomats will need to overcome persistent differences that contributed to the abrupt end of the second summit between Kim and U.S. President Donald Trump in Hanoi Feb. 28.

Trump and Kim initially expressed interest in continuing diplomacy after the Hanoi meeting, but Choe Son Hei, North Korea’s vice minister for foreign affairs, said on March 15 that Pyongyang might halt negotiations because Kim may have “lost the will” to continue talks. She also raised the prospect of North Korea resuming intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) tests, which are prohibited by UN Security Council resolutions, if Washington does not reward the North’s current testing freeze with a reciprocal step that addresses North Korean concerns.

Trump and Kim initially expressed interest in continuing diplomacy after the Hanoi meeting, but Choe Son Hei, North Korea’s vice minister for foreign affairs, said on March 15 that Pyongyang might halt negotiations because Kim may have “lost the will” to continue talks. She also raised the prospect of North Korea resuming intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) tests, which are prohibited by UN Security Council resolutions, if Washington does not reward the North’s current testing freeze with a reciprocal step that addresses North Korean concerns.

North Korea announced in April 2018 a voluntary moratorium on nuclear and long-range missile tests. Trump has highlighted the testing suspension as an indicator of successful talks and announced on Feb. 28 that Kim had agreed to continue abiding by the moratorium.

Choe’s remarks implied that North Korea would undo additional steps it took as part of the process, including the partial dismantlement of its satellite launch facility and nuclear test site, if the United States refuses to take any actions. Satellite imagery from early March reportedly appears to show that North Korea has already reconstructed elements of the Sohae Satellite Launch facility that were dismantled last year. Imagery also suggested that North Korea may be preparing for a launch at the site, but South Korean Defense Minister Jeong Kyeong-doo said on March 18 that the activity at the site “should not be judged as activity preparing for a missile launch.”

Despite North Korea casting doubt on the future of negotiations and raising the prospect of future ICBM tests, U.S. officials have said the Trump administration remains committed to diplomacy.

U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said on March 15 that he is “hopeful” that the United States and North Korea “can continue to have conversations, negotiations.”

The Hanoi summit exposed that the United States and North Korea still prefer different approaches to advancing the goals agreed by Trump and Kim at their first summit in Singapore in June 2018.

North Korea has consistently stated its preference for a step-by-step process in which the United States takes reciprocal actions for progress toward North Korea’s denuclearization. North Korean officials also have made clear that Pyongyang wants the initial U.S. steps to include sanctions relief. The proposal that North Korean Foreign Minister Ri Yong Ho discussed publicly after the Hanoi summit called for lifting the majority of sanctions imposed by the UN Security Council in 2016 and 2017 in return for North Korea dismantling its Yongbyon nuclear complex under U.S. inspections and solidifying its voluntary testing moratorium.

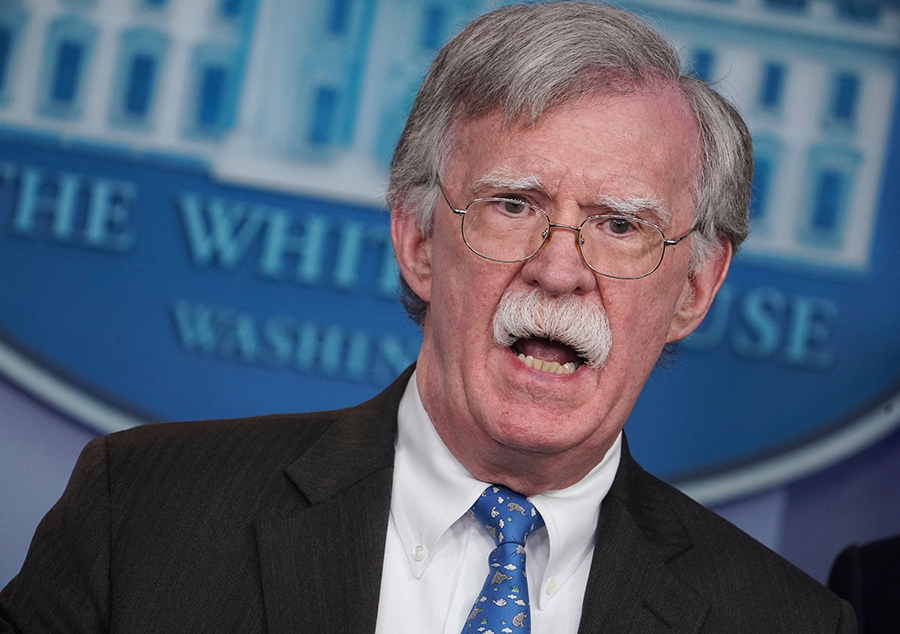

U.S. officials, including National Security Advisor John Bolton in a March 3 interview with CBS, rejected the step-by-step approach outright.

Additionally, although Trump and Kim agreed to the general goals of the negotiating process during their meeting in Singapore, the Trump administration appears to be seeking a more detailed understanding of the term “complete denuclearization of the Korean peninsula,” and the end-state of the negotiations before agreeing on steps to advance the process.

Pompeo made clear in July that the United States and North Korea did not share the same definition of denuclearization. Bolton’s comments March 3 clarified that U.S. officials define denuclearization as the verifiable dismantlement of North Korea’s nuclear weapons program and its means of production, plus an end to the North’s “ballistic missile program, and its chemical and biological weapons programs.”

Trump had made statements indicating the United States would pursue dismantling these programs as part of negotiating process, but it had been unclear if the United States was actually including chemical and biological weapons in its definition of “denuclearization of the Korean peninsula.” The expanded definition puts further distance between the U.S. and North Korean understandings of the term.

North Korea and the United States are also at odds over the sequencing of sanctions relief. Stephen Biegun, U.S. special representative for North Korea, stated in January that Washington is “prepared to discuss many actions that could help build trust between our two countries and advance further progress in parallel on the Singapore summit objectives.” U.S. officials have made clear that those actions do not include sanctions relief, which will not be offered until denuclearization is complete.

The Trump administration has not explicitly stated what steps Washington would be willing to take “in parallel” to North Korean actions to denuclearize, but they may include establishing better ties between the two countries with liaison offices and discussions to bring a formal end to the Korean War. Reportedly, both topics were on the agenda for the Hanoi summit.

In her March 15 remarks, Choe appeared to reject the Trump administration’s approach and said that North Korea has “no intention to yield to U.S. demands” and Pyongyang is not willing to “engage in negotiations of this kind.”

South Korean President Moon Jae-in has been working to bring the United States and North Korea back to negotiations and bridge the divide between their positions. Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha said on March 4 that South Korea is looking to “create a venue for the resumption of the North Korea-U.S. dialogue.”

North Korea Continues to Evade UN Sanctions |