"I find hope in the work of long-established groups such as the Arms Control Association...[and] I find hope in younger anti-nuclear activists and the movement around the world to formally ban the bomb."

Creating an Environment for Nuclear Disarmament: Striding Forward or Stepping Back?

April 2019

By Paul Meyer

Few would contest that the regime built on the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) is currently going through a rough patch, to put it mildly. Long-simmering frustrations with the lack of progress in fulfilling the treaty’s Article VI commitment on nuclear disarmament erupted in recent years in the form of a broadly based humanitarian initiative leading to the 2017 conclusion of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

The new treaty has posed a major challenge to the status quo. Backed by 122 states at the time of its adoption, the treaty has now garnered 70 signatures and 22 ratifications, with 50 ratifications needed for the pact to enter into force. Some nuclear powers, particularly the United States, have begun new initiatives to try to maintain their control over the direction of NPT activity.

The new treaty has posed a major challenge to the status quo. Backed by 122 states at the time of its adoption, the treaty has now garnered 70 signatures and 22 ratifications, with 50 ratifications needed for the pact to enter into force. Some nuclear powers, particularly the United States, have begun new initiatives to try to maintain their control over the direction of NPT activity.

The prevailing nuclear orthodoxy of the NPT community, which relied on the treaty’s five nuclear-weapon states to set the scope and pace of disarmament commitments, has been contested by a super majority of NPT members. These reformers have opted for an alternative path to nuclear disarmament by means of a treaty that rejects and stigmatizes nuclear weapons and the doctrines of nuclear deterrence associated with them. In so doing, they have opened up a fissure within the NPT membership that has put the nuclear-weapon states and their nuclear weapons-dependent allies into the role of a dissident minority, albeit one that possesses the very weapons the reformers seek to eliminate.

This schism will not be readily repaired. On one hand, there are the non-nuclear-weapon states, which have lost faith in the hollow and self-serving pledges of the nuclear-weapon states regarding nuclear disarmament. These states are using the prohibition treaty to embrace a new doctrine. On the other hand, there are the Old Believers who continue to espouse the hallowed texts from decades of NPT meetings that promise nuclear salvation through the so-called step-by-step approach to disarmament. In the NPT context, this has meant increasingly ritualized calls for entry into force of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), which still needs eight ratifications, including the United States and China; the negotiation of a fissile material cutoff treaty (FMCT) within the Conference on Disarmament, a more than 20-year fantasy; and further reductions in the nuclear arsenals of possessing states, a goal undermined by the juggernaut of nuclear force modernization speeding in the opposite direction.

For the United States, the high priest of nuclear orthodoxy, the developments of the last few years have proven disconcerting. The negotiation and completion of the prohibition treaty represents an affront to U.S. authority. With its nuclear-weapon state counterparts, the United States found it easy to denounce this heresy and to press France and the United Kingdom to do likewise.

At the same time, it was difficult to continue to promote the virtue of the step-by-step approach in the face of the contradictory evidence as to its efficacy. This situation has led some in Washington to conclude that a change in tack was required, a discreet modification of the liturgy to deploy during the upcoming NPT services.

A New Approach to Create an Environment for Nuclear Disarmament

The new approach was manifested in a working paper entitled “Creating the Conditions for Nuclear Disarmament” submitted by the United States to the second preparatory committee meeting for the 2020 NPT Review Conference, held in Geneva in 2018. The United States has recently decided to rename the initiative “Creating an Environment for Nuclear Disarmament” (CEND), replacing an empirical term such as “conditions” for the vaguer and more subjectively determined concept of “environment.” The rationale behind the original paper remains the same and its initial paragraph sets out the essence of the problem it perceives with respect to nuclear disarmament: “If we continue to focus on numerical reductions and the immediate abolition of nuclear weapons, without addressing the real underlying security concerns that led to their production in the first place, and to their retention, we will advance neither the cause of disarmament nor the cause of enhanced collective international security.”1 In order “to get the international community past the sterility of such discourse,” the working paper recalls that the United States has previously “spoken in broad terms of the need to create the conditions conducive for further nuclear disarmament” and now “seeks to lay out some of the discrete tasks that would need to be accomplished for such conditions to exist.”

The paper refers to several steps in a wide range of political-security fields ranging from greater acceptance of existing best practices at the more modest end of the spectrum, such as the adoption of an additional protocol to a country’s safeguards agreement based on the International Atomic Energy Agency’s Model Additional Protocol, to fundamental transformations of interstate relations at the ambitious end, such as “a world in which the relationships between nations, especially major powers, are not driven by assumptions of zero-sum geopolitical competition, but are instead cooperative and free of conflict.” In between are conditions on altered threat perceptions, reduced regional tensions, diminished nuclear capabilities, enhanced transparency, comprehensive verification, and effective compliance enforcement measures.

A focus on conditions facilitating nuclear disarmament is not a novel element. Following U.S. President Barack Obama’s celebrated April 2009 speech in Prague invoking the need to move toward a “world without nuclear weapons,” NATO was moved to incorporate these ideas into its authoritative 2010 Strategic Concept. This primordial policy document was adopted at the Lisbon summit in November of that year and is still in force. In it NATO’s leaders state, “We are resolved to seek a safer world for all and to create the conditions for a world without nuclear weapons in accordance with the goals of the [NPT], in a way that promotes international stability, and is based on the principle of undiminished security for all.”2 On the surface, this stance seems aligned with the NPT and its nuclear disarmament goal, but the alliance has never defined these conditions or how it will contribute to their creation. In more recent years, NATO communiqués have stressed that “progress on arms control and disarmament must take into account the prevailing international security environment. We regret that the conditions for achieving disarmament are not favorable today.”3

This stance, however expedient for allies, ignores the reality that the international security environment was hardly any better during the Cold War, yet the alliance made great efforts with considerable success to devise agreements to reduce arms and promote cooperation. Nine years after the Strategic Concept, there is still no more wisdom regarding what NATO deems to be the essential conditions for nuclear disarmament

This stance, however expedient for allies, ignores the reality that the international security environment was hardly any better during the Cold War, yet the alliance made great efforts with considerable success to devise agreements to reduce arms and promote cooperation. Nine years after the Strategic Concept, there is still no more wisdom regarding what NATO deems to be the essential conditions for nuclear disarmament

and how it is helping to achieve those conditions.

No NPT Article VI commitments to cessation of the arms race and to nuclear disarmament are conditioned by the considerations cited in the U.S. paper. At one point, the paper even acknowledged that this “new focus” will require commitments going beyond those embodied in the NPT. Although no author is identified on the U.S. paper, it bears the hallmarks of Assistant Secretary of State Christopher Ford, an official who has served with distinction under Presidents George W. Bush and Donald Trump. Fortunately for those trying to assess the significance of the new departure represented by the CEND initiative, Ford elaborated on the concept in December 2018 remarks about the 2020 NPT Review Conference.4

Ford traced the evolution of the CEND concept to deliberations leading up to the February 2018 U.S. Nuclear Posture Review report and the subsequent preparation of the working paper submitted to the NPT Preparatory Committee in April 2018. “This new initiative aims to move beyond the traditional approach that had focused principally upon ‘step-by-step’ efforts to bring down the number of U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons, but that did so in ways that did not provide a pathway to address the challenge of worsening security conditions, did not address nuclear build-ups by China, India and Pakistan, and did not provide an answer to challenges of deterrence and stability in Europe and the Indo-Pacific, and that had clearly stalled,” says the paper.

A Rejection of the Step-by-Step Approach

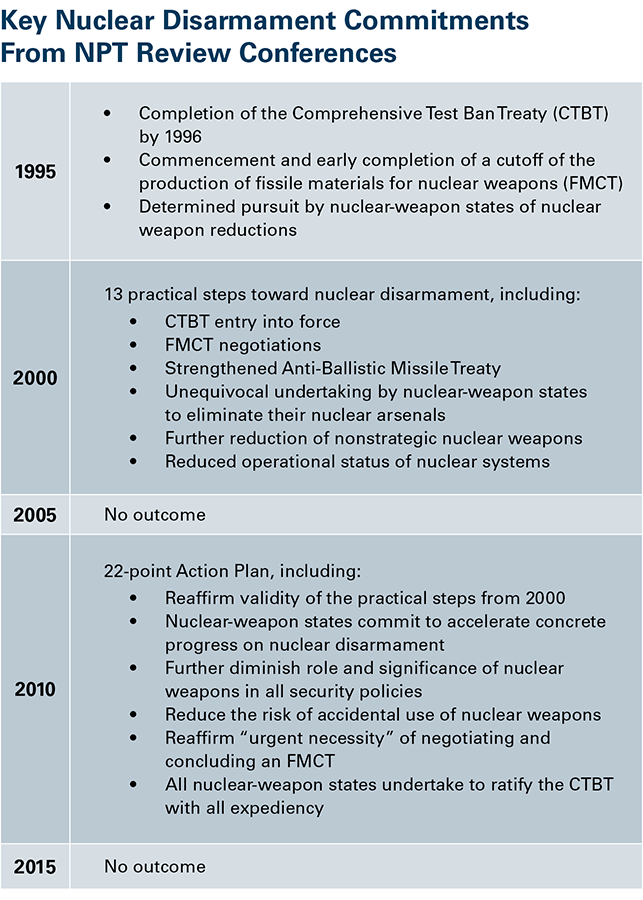

The significance of this appraisal of the effectiveness of the traditional approach on disarmament cannot be overstated. Ford is essentially saying that it has failed and it is time to move beyond it because it has been unable to deliver on earlier NPT review conference agreements, including the CTBT’s entry into force, FMCT negotiations, further reduction of the nuclear-weapon state arsenals, and a diminished role for nuclear weapons in strategic policies.

In addition to this core failure, the traditional approach does not provide a means of countering the current deterioration of security conditions or for addressing the nuclear build-ups of nuclear-armed nations not party to the NPT. According to Ford, a new discourse is required that is “both more realistic than these traditional modes of thought and more consonant with the security challenges facing the real-world leaders whose engagement is essential for disarmament.”

Such a major departure in disarmament diplomacy would normally have been a product of extensive prior consultation with affected allies and partners, but there is no public evidence that this has occurred. Indeed, this new doctrine pulls the carpet from underneath U.S. allies and partners who have dutifully been affirming the superiority of the step-by-step approach to fulfilling the NPT’s nuclear disarmament obligations. Particularly in the context of the diplomatic struggle over the humanitarian initiative and the development of the prohibition treaty, the U.S. nuclear dependents have faithfully argued the merits of the step-by-step, or progressive, approach to achieving nuclear disarmament. One illustration was given at the UN General Assembly First Committee last fall on the part of 30 non-nuclear-weapon states allied with the United States through NATO or bilateral accords. These states declared, “We are firmly committed to the goal of a nuclear-weapon-free-world and believe it is best pursued through a progressive approach consisting of pragmatic, inclusive and effective steps.”5

Such a major departure in disarmament diplomacy would normally have been a product of extensive prior consultation with affected allies and partners, but there is no public evidence that this has occurred. Indeed, this new doctrine pulls the carpet from underneath U.S. allies and partners who have dutifully been affirming the superiority of the step-by-step approach to fulfilling the NPT’s nuclear disarmament obligations. Particularly in the context of the diplomatic struggle over the humanitarian initiative and the development of the prohibition treaty, the U.S. nuclear dependents have faithfully argued the merits of the step-by-step, or progressive, approach to achieving nuclear disarmament. One illustration was given at the UN General Assembly First Committee last fall on the part of 30 non-nuclear-weapon states allied with the United States through NATO or bilateral accords. These states declared, “We are firmly committed to the goal of a nuclear-weapon-free-world and believe it is best pursued through a progressive approach consisting of pragmatic, inclusive and effective steps.”5

Similarly, the most recent Group of Seven consensus statement on nonproliferation and disarmament asserts, “[W]e support further practical and concrete steps in the fields of nuclear arms control, disarmament and nonproliferation.”6 Even the United States and its nuclear-weapon partners France and the United Kingdom remained rhetorically committed to the step-by-step approach until recently. For example, a 2015 explanation of a vote at the First Committee delivered on behalf of the three by the UK ambassador stated, “To create a world without nuclear weapons that remains free of nuclear weapons, however, disarmament cannot take place in isolation of the very real international security concerns that we face. We believe that the step-by-step approach is the only way to combine the imperatives of disarmament and of maintaining global stability.”7

It would seem that “the only way” is receiving a radical reinterpretation in Washington, one that will cause considerable diplomatic heartburn for those allies who have long asserted that the step-by-step approach is the sole viable path toward nuclear disarmament. The attachment of most non-nuclear-weapon states to this position lay in part to the authority these steps had as a result of their inclusion in a succession of consensus outcomes of NPT review conferences, notably those of 1995, 2000, and 2010. The steps could also be assessed more objectively than the general formula of the disarmament commitment in NPT Article VI.

To abandon this approach and its measurable benchmarks in order to embrace the vague and subjective criteria of the new environment discourse will be a difficult policy pill to swallow for those allies who have doggedly supported the mainstream, NPT-centric prescription for achieving nuclear disarmament. It will be particularly difficult for those non-nuclear allies who face significant domestic constituencies disappointed by their governments’ rejection of the prohibition treaty that will press for tangible indications that the step-by-step approach is yielding results. Although supporting a progressive approach toward nuclear disarmament has a positive ring to it, expectations will necessarily build for its proponents to demonstrate actual progress, which is unlikely in the current circumstances. This movement of the policy goalposts also will complicate prospects for success at the 2020 NPT Review Conference, an outcome ardently sought by the non-nuclear-weapon states, especially in the wake of the failed 2015 review conference.

A Problematic Model for Operationalizing the Concept

It is not only the doctrinal switch that Ford has introduced that may prove problematic, but also his concept as to how this new environment discourse is to be operationalized. His model for a Creating the Conditions Working Group is the earlier International Partnership for Nuclear Disarmament Verification, a U.S.-initiated process launched in 2014 that currently has some 25 participating states. The partnership has been geared to studying the verification procedures and technologies that would need to be developed to support nuclear disarmament. Its first phase ended in 2017 with the identification of 14 steps key to the nuclear weapons dismantlement process, and a second phase is currently underway with a view to tabling a final report at the 2020 NPT Review Conference. The partnership reached out to a variety of states, but a majority of its members are U.S. allies. Russia and China, which initially attended partnership meetings as observers, are apparently no longer participating.

In Ford’s view, the working group would consist of 25 to 30 countries “selected on the basis of both regional and political diversity” but filtered by a prior commitment to the new approach. States would be invited to comment on the “key issues that, if addressed effectively, could improve prospects for progress on nuclear disarmament” on the basis of the 2018 U.S. paper intending to agree on such a list as an “initial deliverable” for the working group. Ford envisages the establishment of up to three subgroups to be assigned a specific functional topic and with co-chairs “chosen from among states and individuals most able to provide constructive contributions.” Washington presumably will be making these choices because Ford states that the United States will organize and staff an executive secretariat to oversee the exercise. It is projected that planning for the new working group will be underway by the time of the NPT preparatory committee meeting this month and the working group will be fully operational before the 2020 review conference.

Such a “made in the USA” concept for implementing a multilateral effort is likely to meet resistance from several quarters, most notably from the non-allied nuclear-weapon states but also from partners that may fear that the enterprise will be too controlled and its areas of inquiry too constrained by U.S. preferences.

After decades of espousing practical measures for disarmament, non-nuclear allies will be sensitive to charges that the CEND initiative represents a huge distraction from the effort to achieve measurable progress in achieving the existing disarmament commitments agreed by all NPT parties. With its implication that little can be done in terms of progress on disarmament obligations until a broad spectrum of conditions are met, the CEND initiative risks being viewed as a talk shop disconnected from the disarmament process in which states are discussing how a conflict-free halcyon future for the world can be realized.

Conclusions and Alternative Recommendations

Those concerned with the NPT’s fate will not find the new U.S. approach reassuring. Not only does it undermine years of consistent allied support for an approach to nuclear disarmament grounded in the NPT and the political commitments made in successive review conferences, it suggests that these allies have been unrealistic and mistaken in their policies. By proposing that the agreed NPT benchmarks on nuclear disarmament should be ignored in favor of developing a new list of conditions that would facilitate an eventual disarmament progress, the United States is raising the bar on such progress and linking it to transformations in the international security landscape far removed from NPT-specified obligations.

To have a diplomatic strategy that offers some prospects of bridging the acute differences among NPT members at the 2020 review conference, the United States and other nuclear-weapon states should consider several measures.

Instead of investing in the new working group process with its attendant risks, they must ensure that any new mechanism to support the NPT is grounded in the actual legal and political commitments of the treaty. This could include an open-ended working group of NPT parties to examine the impediments to progress in realizing the specific nuclear disarmament-related steps agreed within the NPT process. Such an initiative would be rooted in the collective results of previous NPT proceedings and could be presented as such rather than as a quixotic pursuit of benign relations among states.

An effort should be made to accept the proposals developed over the last years to enhance transparency as part of a strengthened NPT review process, as agreed when the treaty was indefinitely extended in 1995. Although many non-nuclear-weapon states have called for greater transparency from the nuclear-weapon states, the carefully considered proposals of the 12-member Nonproliferation and Disarmament Initiative (NPDI) merit special attention.8 Not only are these proposals relevant and substantive in themselves, but cooperation with the NPDI group, which comprises supporters and opponents of the prohibition treaty, would make diplomatic sense in any broader effort to repair the rift within the NPT. NPDI members include several prominent and influential NPT parties, and for the nuclear-weapon states to persist in their dismissal of their constructive contribution is only going to further sap any bridge-building efforts at the review conference.

The results of the work undertaken by the International Partnership for Nuclear Disarmament Verification should be introduced into the review conference in a manner that suggests that it will facilitate actual nuclear disarmament steps. Demonstrations on how these verification approaches can be applied to real-world dismantlement of surplus nuclear weapons and fissile material would go a long way toward proving that the partnership is more than an interesting academic endeavor.

The nuclear-weapon states should tamp down their anti-prohibition treaty rhetoric in the lead-up to the review conference. It might be satisfying in a debating club context to denounce treaty supporters as engaging in “magical thinking” or “conditions-blind” absolutism, but the 122 states that have expressed support for the prohibition treaty are all NPT parties whose support will be necessary to arrive at any substantive consensus outcome for the 2020 review conference. A more respectful and diplomatic discourse is in order.

Finally, the greatest positive contribution to the NPT review conference would be tangible demonstrations by the nuclear-weapon states, particularly the United States and Russia, of their commitment to nuclear disarmament by means of further reduction of actual arsenals, the exercise of restraint in any modernization plans, and the resumption of strategic dialogues and cooperative arms control arrangements.

For friends of the NPT, the lead-up to the 2020 review conference is fraught with difficulties, none more significant than the chasm that has opened between varying concepts of effectuating NPT obligation on nuclear disarmament. Although out-of-the-box thinking is always welcome in disarmament diplomacy, it should be based on the cumulative legal and political commitments of the NPT, the most universal agreement on nuclear affairs. Demonstrating compliance with these commitments is the surest route for reinforcing the NPT’s authority during this period of crisis. To ignore this approach risks creating the conditions for nuclear disaster rather than nuclear disarmament.

ENDNOTES

1. Preparatory Committee for the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Creating the Conditions for Nuclear Disarmament (CCND): Working Paper Submitted by the United States,” NPT/CONF.2020/PC.II/WP.30, April 18, 2018.

2. NATO, “Active Engagement, Modern Defence: Strategic Concept for the Defence and Security of the Members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation,” n.d., para. 26, www.nato.int/lisbon2010/strategic-concept-2010-eng.pdf (adopted November 19, 2010).

3. NATO, “North Atlantic Council Statement on the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” September 20, 2017, https://www.nato.int/cps/us/natohq/news_146954.htm

4. Christopher Ashley Ford, “The P5 Process and Approaches to Nuclear Disarmament: A New Structured Dialogue,” Remarks to Wilton Park conference, December 10, 2018, https://www.state.gov/t/isn/rls/rm/2018/288018.htm.

5. “Statement on the Progressive Approach,” October 18, 2018, http://reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Disarmament-fora/

1com/1com18/statements/18Oct_Group.pdf.

6. Group of Seven, “G7 Statement on Non-Proliferation and Disarmament,” April 11, 2017, http://www.g7.utoronto.ca/foreign/170411-npdg_statement_-_final_.pdf.

7. “Explanation of Vote Before the Vote by Ambassador Matthew Rowland, UK Permanent Representative to the Conference on Disarmament on Behalf of France, the United Kingdom and the United States,” November 2, 2015.

8. Preparatory Committee for the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Proposals by the Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Initiative to Enhance Transparency for Strengthening the Review Process for the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons,” NPT/CONF.2020/PC.II/WP.26, April 11, 2018.

Paul Meyer is a fellow in international security at Simon Fraser University and a senior fellow at The Simons Foundation in Vancouver, Canada. He served in an array of international security positions during a 35-year diplomatic career with the Canadian Foreign Service.