“For 50 years, the Arms Control Association has educated citizens around the world to help create broad support for U.S.-led arms control and nonproliferation achievements.”

The NPT and the Conditions for Nuclear Disarmament

April 2019

By Daryl G. Kimball, Executive Director

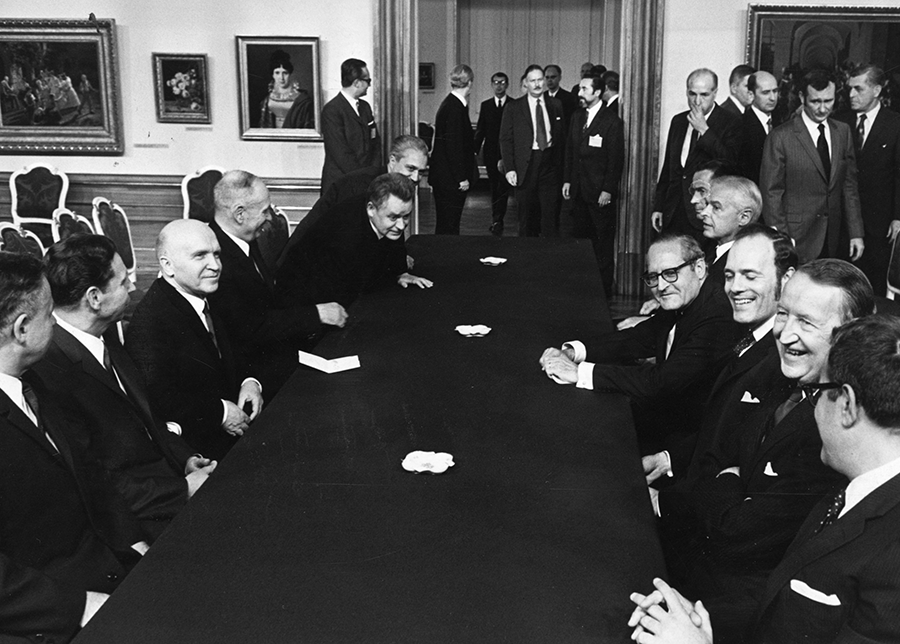

Fifty years ago, shortly after the conclusion of the 1968 nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), the United States and the Soviet Union launched the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT). Negotiated in the midst of severe tensions, the SALT agreement and the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty were the first restrictions on the superpowers’ massive strategic offensive weapons, as well as on their emerging strategic defensive systems. The SALT agreement and the ABM Treaty slowed the arms race and opened a period of U.S.-Soviet detente that lessened the threat of nuclear war.

The size of U.S. and Russian nuclear stockpiles has decreased significantly from their Cold War peaks, but the dangers posed by the still excessive arsenals and launch-under-attack postures are even now exceedingly high.

The size of U.S. and Russian nuclear stockpiles has decreased significantly from their Cold War peaks, but the dangers posed by the still excessive arsenals and launch-under-attack postures are even now exceedingly high.

Further progress on nuclear disarmament by the United States and Russia has been and remains at the core of their NPT Article VI obligation to “pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament.”

But as the 2020 NPT Review Conference approaches, the key agreements made by the world’s two largest nuclear powers are in severe jeopardy. Dialogue on nuclear arms control has been stalled since Russia rejected a 2013 U.S. offer to negotiate nuclear cuts beyond the modest reductions mandated by the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START).

More recently, the two sides have failed to engage in serious talks to resolve the dispute over Russian compliance with the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, which will likely be terminated in August. Making matters worse, talks on extending New START, which is due to expire in 2021, have not begun.

Last year, Russia said it was interested in extending New START, but Team Trump will only say it remains engaged in an interagency review of the treaty. That review is led by National Security Advisor John Bolton, who publicly called for New START’s termination shortly before he joined the administration.

New START clearly serves U.S. and Russian security interests. The treaty imposes important bounds on the strategic nuclear competition between the two nuclear superpowers. Failure to extend New START, on the other hand, would compromise each side’s understanding of the others’ nuclear forces, open the door to unconstrained nuclear competition, and undermine international security. Agreement to extend New START requires the immediate start of consultations to address implementation concerns on both sides.

Instead of agreeing to begin talks on a New START extension, U.S. State Department officials claim that “the United States remains committed to arms control efforts and remains receptive to future arms control negotiations” but only “if conditions permit.”

Such arguments ignore the history of how progress on disarmament has been and can be achieved. For example, the 1969–1972 SALT negotiations went forward despite an extremely difficult geostrategic environment. As U.S. and Russian negotiators met in Helsinki, President Richard Nixon launched a secret nuclear alert to try to coerce Moscow’s allies in Hanoi to accept U.S. terms on ending the Vietnam War, and he expanded U.S. bombing into Cambodia and Laos. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union sent 20,000 troops to Egypt to back up Cairo’s military campaign to retake the Sinai Peninsula from Israel. In late 1971, Nixon risked war with the Soviet Union and India to help put an end to India's 1971 invasion of East Pakistan.

Back then, the White House and the Kremlin did not wait until better conditions for arms control talks emerged. Instead, they pursued direct talks to achieve modest arms control measures that, in turn, created a more stable and predictable geostrategic environment.

Today, U.S. officials, such as Christopher Ford, assistant secretary of state for international security and nonproliferation, argue that the NPT does not require continual progress on disarmament and that NPT parties should launch a working group to discuss how to create an environment conducive for progress on nuclear disarmament.

Dialogue between nuclear-armed and non-nuclear-weapon states on disarmament can be useful, but the U.S. initiative titled “Creating an Environment for Nuclear Disarmament” must not be allowed to distract from the Trump administration’s lack of political will to engage in a common-sense nuclear arms control and risk reduction dialogue with key nuclear actors.

The current environment demands a productive, professional dialogue between Washington and Moscow to extend New START by five years, as allowed by Article XIV of the treaty; to reach a new agreement that prevents new deployment of destabilizing ground-based, intermediate-range missiles; and maintain strategic stability and reduce the risk of miscalculation.

Ahead of the pivotal 2020 NPT Review Conference, all states-parties need to press U.S. and Russian leaders to extend New START and pursue further effective measures to prevent an unconstrained nuclear arms race. Failure to do so would represent a violation of their NPT Article VI obligations and would threaten the very underpinnings of the NPT regime.