"I find hope in the work of long-established groups such as the Arms Control Association...[and] I find hope in younger anti-nuclear activists and the movement around the world to formally ban the bomb."

Nuclear Deterrence: Megatons in a Minibook

March 2019

Reviewed by Henry Sokolski

Assessing the effectiveness of nuclear deterrence is a bit like attempting the illicit mathematical operation of dividing an integer by zero: in both cases, you can get almost any answer you want. That, however, is not to argue that what is thought to deter does not matter. It does. If enough people think a nuclear force will or will not deter specific kinds of aggression, this has serious military operational implications, which war planners ignore at their peril. As a consequence, the literature on nuclear deterrence is nuanced, contradictory, complicated, and vast. It would be nice if things were simplified.

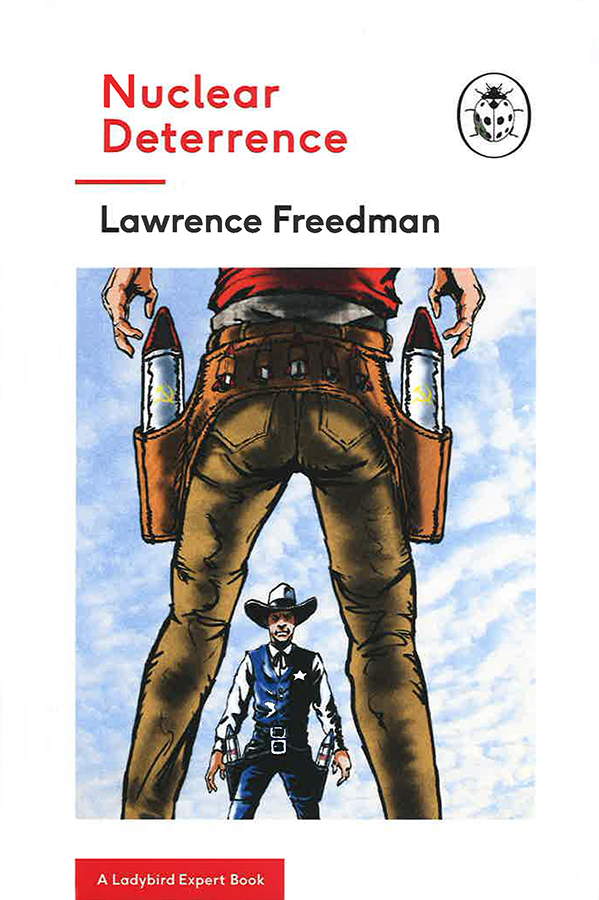

Enter Lawrence Freedman with a 7,000-word minibook, Nuclear Deterrence, written to be accessible. Freedman’s minibook runs just 50 small pages, 25 of which are full-page color illustrations.

Enter Lawrence Freedman with a 7,000-word minibook, Nuclear Deterrence, written to be accessible. Freedman’s minibook runs just 50 small pages, 25 of which are full-page color illustrations.

Some might view such an abbreviation as excessive. After all, the author’s previous work on things nuclear, The Evolution of Nuclear Strategy (2000), ran close to 500 pages. His more modest tome, Deterrence (2004), ran no fewer than 160 pages.

What can 25 short sheets on this topic offer? More than one might think. For the uninitiated, there is basic science on the construction of the first bombs. For the upperclassman, there’s a useful history from the start of the Manhattan Project to President Donald Trump. Think of Nuclear Deterrence as a conversation starter.

The book also focuses on the headaches ahead. Besides Iran and North Korea, nuclear terrorism, Russia, and China, the book lifts the veil on future headlines. What if the current invulnerability of nuclear ballistic missile submarines is eliminated by some technical breakthrough? What if nuclear command and control systems are disabled by cyberattacks? Might Egypt and Saudi Arabia go nuclear if Iran does? What if terrorists, not states, attacked major states with nuclear arms? What if major states use nuclear weapons? Depending on the answers, faith in the future utility of nuclear deterrence could crumble.

One could add to the list. Deterring and balancing nuclear forces against the Soviets was one thing, but deterring China and Russia today is two and therefore far more demanding qualitatively and quantitatively. With the prospect of other states getting their fingers on nuclear forces of their own, the old bugaboo of catalytic wars that begin conventionally or with nuclear threats but end in superpower nuclear dares or worse seems far more likely—think of a Suez-styled Syria crisis but with all key parties laded with nuclear arms.

Also, since the Cold War, completely new domains of strategic war have emerged. There are now major military scientific advances in space, cybertechnologies, artificial intelligence, hypersonics, precision guidance, robotics, and synthetic biology. Will states mistakenly presume a strategic advantage in these domains that might prompt them to take imprudent risks in a still massively nuclear-armed world? In this case, how might nuclear deterrence end?

All of these future-related questions demand attention, not just from experts but of lay citizens. Presumably, the point of Nuclear Deterrence is to get this public discourse ball rolling. In this case, it would make sense if a U.S. edition of this book was made available, as well as Chinese, Indian, Iranian, Israeli, Japanese, Korean, Pakistani, and Russian editions.