"I find hope in the work of long-established groups such as the Arms Control Association...[and] I find hope in younger anti-nuclear activists and the movement around the world to formally ban the bomb."

July/August 2005

Edition Date

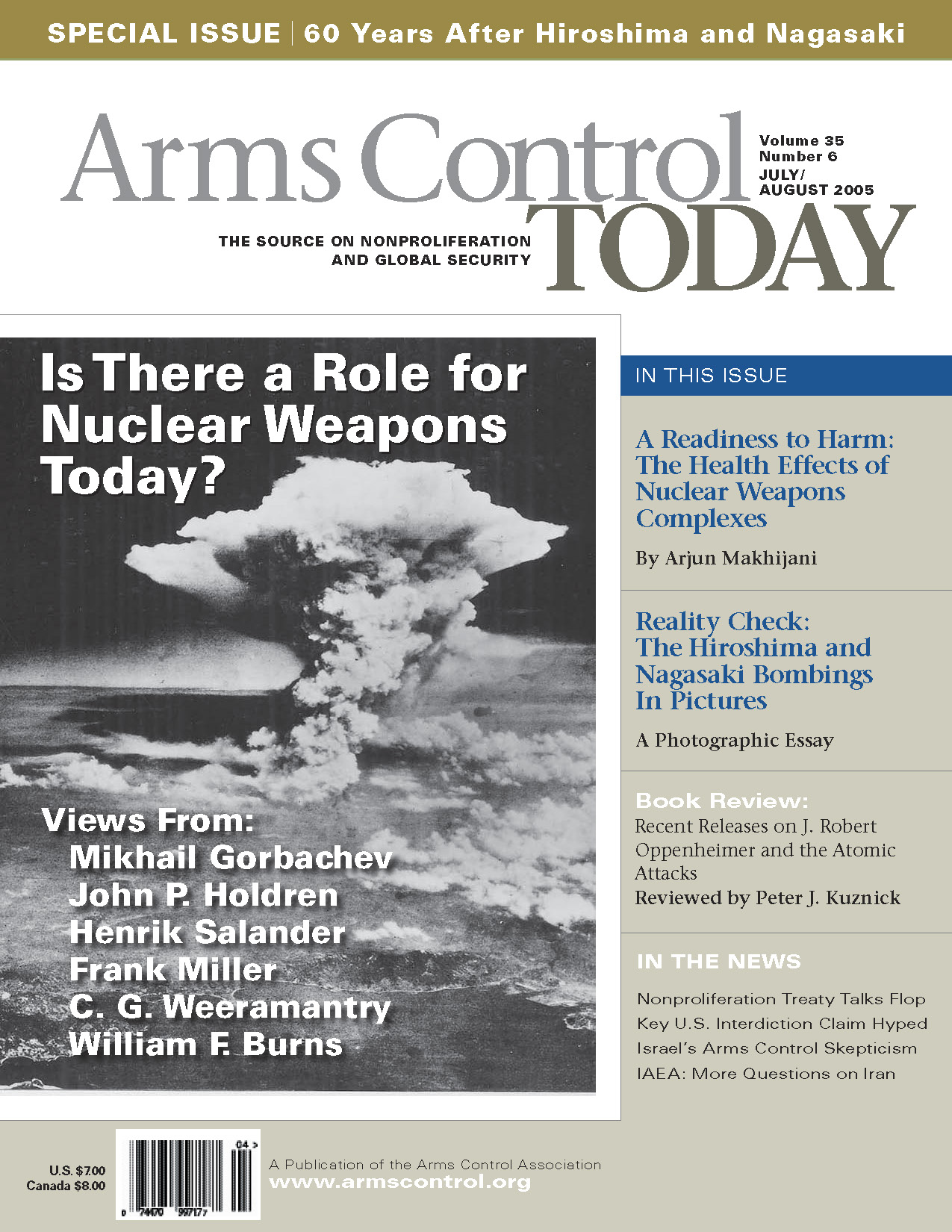

Cover Image

Authored by on October 18, 2016

Authored by on July 1, 2005

Authored by on July 1, 2005

Authored by on July 1, 2005

Authored by on July 1, 2005

Authored by on July 1, 2005

Authored by on July 1, 2005

Authored by on July 1, 2005

Authored by on July 1, 2005

Authored by on July 1, 2005