"No one can solve this problem alone, but together we can change things for the better."

Missing Voices: The Continuing Underrepresentation of Women in Multilateral Forums on Weapons and Disarmament

December 2017

By Elizabeth Minor

The recently adopted Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons contains much that is unprecedented for an international nuclear weapons agreement.

Consistent with the treaty’s humanitarian foundations, its preamble recognizes victims of nuclear weapons use and testing.1 An article on victim assistance obligates states-parties for the first time to respond to affected individuals’ rights and needs through an international framework. Obligations on environmental remediation represent a similarly novel step forward. The preamble’s recognition of the disproportionate impact of nuclear weapons activities on indigenous peoples is also a first for arms treaties. These are major achievements.

There is a further element of the preamble that is welcome and unprecedented in arms treaties: the commitment to “supporting and strengthening the effective participation of women in nuclear disarmament.” The treaty recognizes that “the equal, full and effective participation of both women and men is an essential factor for the promotion and attainment of sustainable peace and security.”2 This recognition and commitment is useful and significant for highlighting the need for change and for offering the opportunity to review progress at future meetings of the treaty’s parties.

There is a further element of the preamble that is welcome and unprecedented in arms treaties: the commitment to “supporting and strengthening the effective participation of women in nuclear disarmament.” The treaty recognizes that “the equal, full and effective participation of both women and men is an essential factor for the promotion and attainment of sustainable peace and security.”2 This recognition and commitment is useful and significant for highlighting the need for change and for offering the opportunity to review progress at future meetings of the treaty’s parties.

This article looks at some of the patterns in women’s representation at international meetings of multilateral forums dealing with arms matters in recent years. The gender picture is currently far from balanced. Although this article looks at the numbers, achieving equal participation in multilateral forums is a matter that goes beyond securing parity in attendance and speakers at meetings. Further, successfully integrating gendered perspectives and improved attitudes to gender equality could be of greater significance than simple numerical equality to the outcomes these forums can generate for women and men affected worldwide by the weapons issues they discuss. These are all important issues for policymakers and civil society to consider in addressing gender and marginalization in multilateral forums.

Gender Imbalance at the Ban Talks

The final treaty text recognizes the importance of women’s participation, but imbalances in representation were seen at the negotiations on the prohibition treaty, where 31 percent of registered country delegates were women3 and women gave 29 percent of publicly available country statements.4 Although noteworthy that the negotiations were led by Costa Rican Ambassador Elaine Whyte Gómez, women headed only 19 (15 percent) state delegations. Thirty-one percent of delegations were composed entirely of men, with 3 percent of delegations all female. On the composition of the 125 registered country delegations, 65 had more men than women (including 39 all-male delegations); 15 had equal numbers of men and women; and 45 had more women than men (including four all-female delegations).5

These patterns are nevertheless higher than the averages seen in data analyzed by Article 36 on women’s participation on state delegations at 13 multilateral forums and processes dealing with weapons and disarmament between 2010 and 2014.6 Those forums and processes included those dealing with conventional weapons and weapons of mass destruction.7

Recent studies using similar data over longer periods of time suggest a general upward trend in women’s representation on state delegations over recent decades. For example, a 2016 study recorded an increase of more than 20 percent since 1980 in women’s representation on official delegations at multilateral forums dealing with security issues.8

Recent studies using similar data over longer periods of time suggest a general upward trend in women’s representation on state delegations over recent decades. For example, a 2016 study recorded an increase of more than 20 percent since 1980 in women’s representation on official delegations at multilateral forums dealing with security issues.8

The patterns recorded at the prohibition treaty negotiations, although showing significant inequality, may therefore be part of a general trend toward more equal representation in such forums. If the current rate of progress is maintained, however, achieving equal gender representation could take many decades.

Women’s Participation 2010-2014

For its study, Article 36 gathered data on women’s attendance, leadership of delegations, and delivery of statements or expert presentations.9 It examined patterns in representation among states and civil society, including nongovernmental organizations, academic institutions, and others, such as religious groups. Civil society performed better in the available data, but states and civil society remained far from the equal representation of women and men.

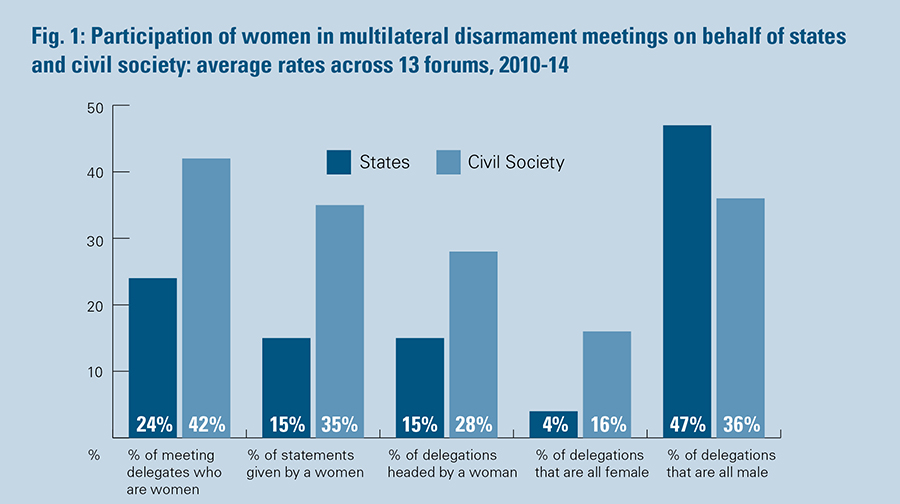

At any given meeting of the forums studied, only about one-quarter of official country delegates were likely to be women, and less than one-fifth of statements were likely to be given by a woman. Almost half of all country delegations at any of these meetings were likely to be composed entirely of men. Women headed 15 percent of delegations on average.

On average at meetings, less than half of civil society delegates were women, and more than one-third of civil society delegations were likely to be all male, with 16 percent of delegations all female. Women headed roughly twice the proportion of civil society delegations as state delegations on average, with women giving more than twice the proportion of civil society interventions as state interventions, across the available data (fig. 1).

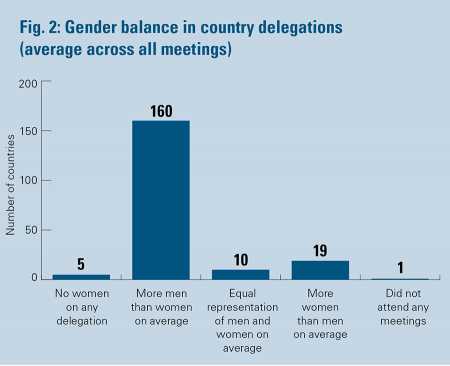

The gender balance within country delegations also starkly illustrated the overrepresentation of men in these forums and processes. Only 10 of the 195 countries and territories for which Article 36 gathered participation data had equal numbers of men and women on their delegations on average, across five years of the meetings of 13 forums. One hundred sixty countries’ delegations had more men than women on average. Five did not include women on any delegations for the meetings for which data were available (fig. 2).

Of the 143 civil society organizations for which information was available about the representation of men and women on delegations, 17 had equal numbers of men and women on their delegations on average. Forty-two had more women than men on their delegations on average, including 29 whose delegations were always all female. Fifty-four civil society organizations sent only men to the meetings they attended.

Women’s leadership and representation on state delegations

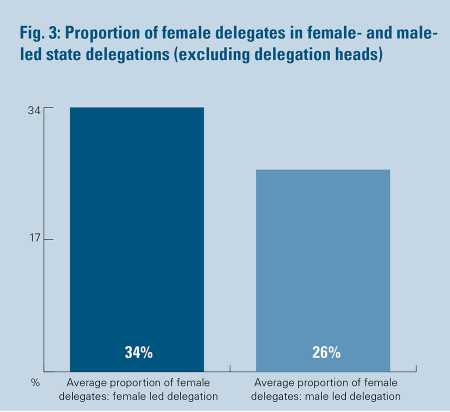

A clear relationship was seen in the data across the meetings between the gender of the head of a country delegation and the proportion of women on a delegation. On average, the data showed a considerably higher proportion of women were included on female-headed delegations, compared to those led by a man. Figure 3 shows the average proportions, with the numbers excluding the delegation heads themselves.

This pattern in the data appears to indicate the importance of women’s leadership to the question of representation, but it cannot reveal the mechanism. Initiatives to increase the proportion of women in higher positions in countries’ foreign services may accelerate the pace of change toward more equal representation.

This pattern in the data appears to indicate the importance of women’s leadership to the question of representation, but it cannot reveal the mechanism. Initiatives to increase the proportion of women in higher positions in countries’ foreign services may accelerate the pace of change toward more equal representation.

Country income group, region, and women’s representation on state delegations

Analysis revealed variations in the representation of women on country delegations between regional groups and countries of different income categories.10

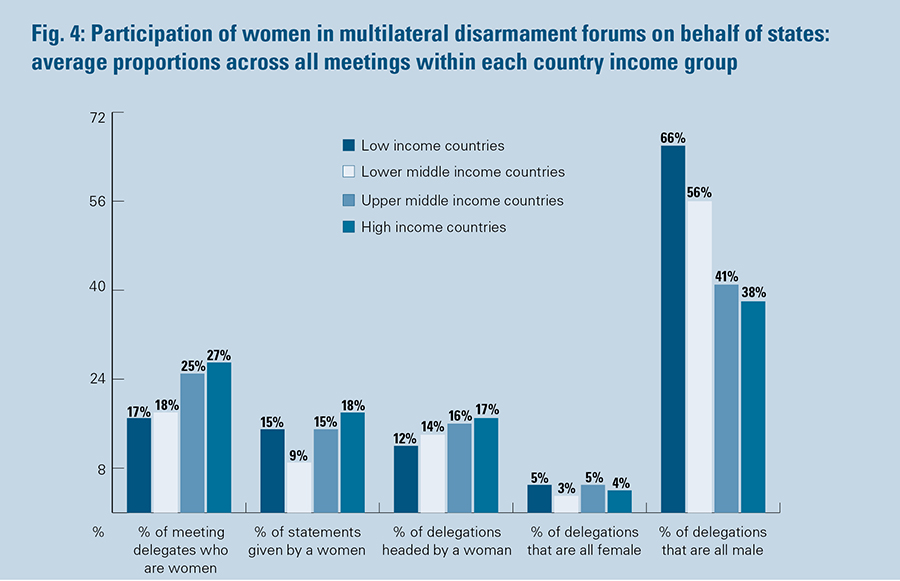

Of the delegates attending any given meeting for low-income countries, the proportion of women was on average lower than the proportion attending for higher-income countries. A similar pattern was seen for heads of delegations. A higher proportion of lower-income country delegations were also all male on average, compared to the delegations of higher-income countries (fig. 4).

Article 36’s broader study showed that lower-income countries were significantly underrepresented in multilateral disarmament forums, indicative of their broader marginalization.11 Why these countries have lower average rates of women’s representation cannot be determined from this data, but it suggests that, in addressing issues of underrepresentation, it is important to investigate how different forms of marginalization may intersect.

Variation was also seen in looking at patterns by region, suggesting the utility of regionally based initiatives to improve women’s participation. African and Asia-Pacific countries had the lowest average proportions of women delegates and delegation heads. On the other hand, Latin American and Caribbean countries had the highest proportions of women delegates and delegation heads.

Improving the Picture

The patterns described illustrate one aspect of the relative marginalization of women in international forums, recognition of which has grown over recent years. Women’s marginalization, however, is an issue that goes far beyond international forums and specific policies that can be adopted in relation to them. Yet, some recommendations can be made.

A first necessary step to addressing patterns of underrepresentation is the consistent monitoring and analysis of data, which should be supported by states and others, whether done by international or official bodies or civil society monitoring organizations.12 Highlighting patterns and assessing any steps taken to address them against available data represent a first level of action.

A first necessary step to addressing patterns of underrepresentation is the consistent monitoring and analysis of data, which should be supported by states and others, whether done by international or official bodies or civil society monitoring organizations.12 Highlighting patterns and assessing any steps taken to address them against available data represent a first level of action.

Article 36 interviewed a limited number of representatives from states, international organizations, and civil society for its study. Most state respondents stated that women’s representation was an important issue for their country, with some considering that they were likely performing well without a formal policy (a national policy on gender balance or diversity was only reported by one respondent). This was clearly unsupported by the data collected. Others welcomed initiatives to raise awareness on this issue, including the civil society initiative on all-male panels.13 States should highlight the issue of underrepresentation in the appropriate forums to keep this on the political agenda and adopt formal policies on it nationally.

Steps such as increasing women’s leadership, working regionally, and examining the intersection of different forms of marginalization could have an impact on women’s representation in international forums and processes on arms. Where states are involved in the administration or funding of sponsorship programs for meetings of international forums, they should consider adopting policies, such as that suggested by the UN Development Programme, requiring that half of any budget be spent on sponsoring men and half on women, with funding to be held back where funds are unspent in either category. Such policies can assist in the greater inclusion and increased capacity of female experts who may be overlooked due to wider structural factors, although it would not directly reach unsponsored delegations.

Gender intersects with arms issues in numerous ways, of which the underrepresentation of women at diplomatic meetings is one. For example, gendered discussion of violence and weapons, which may frame certain weapons as symbols of masculine strength and women as being in need of male protection, can shape how disarmament issues are addressed, as well as exacerbate women’s exclusion from these processes.14 Women, men, boys, and girls also can be exposed to different patterns of violence and affected differently by specific weapons and practices.15

Gender intersects with arms issues in numerous ways, of which the underrepresentation of women at diplomatic meetings is one. For example, gendered discussion of violence and weapons, which may frame certain weapons as symbols of masculine strength and women as being in need of male protection, can shape how disarmament issues are addressed, as well as exacerbate women’s exclusion from these processes.14 Women, men, boys, and girls also can be exposed to different patterns of violence and affected differently by specific weapons and practices.15

The achievement of the equal representation of men and women at international meetings would not guarantee that women’s voices would be heard equally or that processes or forums dealing with arms would adequately address gendered issues. Doing so is not a product of the sex of the individuals involved in discussions. Fundamentally challenging the framing of discussions, how women are addressed within them, and facilitating the promotion of progressive initiatives by women and men must be addressed in order to achieve this.

Nevertheless, it is important to confront women’s underrepresentation and other patterns of marginalization in these forums alongside other objectives, such as ensuring the participation of those that have been most affected by the issues under discussion and the consideration of humanitarian perspectives. States and civil society can adopt policies and undertake monitoring and analysis toward these objectives.

‘Organizations With More Diverse Teams Make Better Decisions’ Michèle Flournoy is co-founder and chief executive officer of the Center for a New American Security. From February 2009 to February 2012, she served as undersecretary of defense for policy, the most senior executive position held by a women in Defense Department history.

Flournoy: It's important for a number of reasons. One is as a matter of principle. As a healthy democracy, you want your national security cadre to look like America. As a matter of performance, all of the business literature suggests that organizations with more diverse teams make better decisions. In the business world, they're actually shown to be more profitable, higher performance. Then, from simply a fairness perspective and an access-to-talent perspective, why would you not access half of your population to try to bring them into leadership positions in this field or any other? There are more women in the national security field than ever before, but they are not fully represented in the leadership ranks. I think there are a number of reasons for that. There are systemic barriers where there are often unintended obstacles to women's progression. Then there may be other societal and social factors that also figure in. I was part of a task force at the CIA that looked at diversity. The agency had entry-level classes of intelligence officers that were 50/50 men and women, but by the time 10, 12, 13 years in, when people were being considered for senior intelligence service, the pool was about 25 percent women. The question was why, what was happening? What was causing the falloff? It was a mixture of factors. There were issues of work-life balance. There was lots of investing tremendously in the training and development of women, and yet the agency was just letting them leave because it was inflexible in allowing them a little bit of work flexibility to have families and then making no effort to bring them back. Women don't lose their brains when they have children. There's a lot that figures into this, and each organization is different. We have to take a much more systemic approach to keeping women in the pipeline and giving women access to achieving their full potential and serving at the highest levels. There are lots of ways to do that which are very much worth doing, not very costly, and with very high payoff. |

ENDNOTES

1. Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, 2017, https://treaties.un.org/doc/Treaties/2017/07/20170707%2003-42%20PM/Ch_XXVI_9.pdf.

2. Ibid., preamble. For relevant documents where the importance of women’s participation has previously been recognized, see UN Security Council, S/RES/1325, October 31, 2000; UN Department of Public Information, “Goal 5: Achieve Gender Equality and Empower All Women and Girls,” n.d., http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/; UN General Assembly, “Women, Disarmament, Non-proliferation and Arms Control,” A/RES/65/69, January 13, 2011; UN General Assembly, “Women, Disarmament, Non-proliferation and Arms Control: Report of the Secretary-General,” A/68/166, July 22, 2013; UN General Assembly, “Report of the Fifth Biennial Meeting of States to Consider the Implementation of the Programme of Action to Prevent, Combat and Eradicate the Illicit Trade in Small Arms and Light Weapons in All Its Aspects,” A/CONF.192/BMS/2014/2, June 26, 2014; UN Security Council, S/RES/2117, September 26, 2013; UN Security Council, S/RES/2200, February 12, 2015.

3. See UN General Assembly, “United Nations Conference to Negotiate a Legally-Binding Instrument to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons, Leading Towards Their Total Elimination: List of Participants,” A/CONF.229/2017/INF/4/Rev.1, July 25, 2017.

4. See Reaching Critical Will, “Statements From the Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty Negotiations,” 2017, http://www.reachingcriticalwill.org/disarmament-fora/nuclear-weapon-ban/statements. Data on speaking in closed sessions are not available.

5. Article 36 acknowledges gender diversity beyond the binary categorization of “men” and “women.” These are used in this paper as the categorizations available in the source data discussed.

6. During 2015 and 2016, Article 36 conducted a study into patterns in underrepresentation at multilateral forums dealing with weapons and disarmament, from which this article draws. For the full results and notes on methodology, see Elizabeth Minor, “Disarmament, Development and Patterns of Marginalisation in International Forums,” Article 36, April 2016, http://www.article36.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/A36-Disarm-Dev-Marginalisation.pdf. See also “Women and Multilateral Disarmament Forums: Patterns of Underrepresentation,” Article 36, October 2015, http://www.article36.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Underrepresentation-women-FINAL1.pdf. (containing further information on methodology.)

7. The forums or processes on which data were collected were the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty; international conferences on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons; meetings on the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, the Biological Weapons Convention, the Chemical Weapons Convention, the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, the Convention on Cluster Munitions, the Arms Trade Treaty, the UN Programme of Action on Small Arms and Light Weapons, the UN General Assembly First Committee, the Conference on Disarmament, and the UN Disarmament Commission.

8. International Law and Policy Institute (ILPI) and UN Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR), “Gender, Development and Nuclear Weapons: Shared Goals, Shared Concerns,” October 2016, http://nwp.ilpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/ILPI-UNIDIR-gender-and-nuclear-weapons.pdf. See Mothepa Shadung, “In the Debate Towards Nuclear Disarmament, Where Are All the Women?” Institute for Security Studies, August 26, 2015, https://issafrica.org/iss-today/in-the-debate-towards-nuclear-disarmament-where-are-all-the-women; Kathleen Danskin and Dana Perkins, “Women as Agents of Positive Change in Biosecurity,” Science and Diplomacy, Vol. 3, No. 2 (June 2014), http://www.sciencediplomacy.org/files/women_as_agents_of_positive_change_in_biosecurity_science__diplomacy.pdf.

9. Data on the sex of speakers was much more limited than on that of attendees. See “Women and Multilateral Disarmament Forums.”

10. Using categorizations from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Development Assistance Committee. See Minor, “Disarmament, Development and Patterns of Marginalisation in International Forums.”

12. Article 36’s project relied heavily on data collected by Reaching Critical Will in the course of its work to monitor disarmament forums.

13. See “Say No to #ManPanels,” n.d., http://www.manpanels.org.

14. See ILPI and UNIDIR, “Gender, Development and Nuclear Weapons.”

15. See Reaching Critical Will, “Women and Explosive Weapons,” 2014, http://www.reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Publications/WEW.pdf; Article 36 and Reaching Critical Will, “Sex and Drone Strikes: Gender and Identity in Targeting and Casualty Analysis,” 2014, http://www.reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Publications/sex-and-drone-strikes.pdf; Reaching Critical Will, “Gender-Based Violence and the Arms Trade Treaty,” 2015, http://www.reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Publications/GBV_ATT-brief.pdf.

Elizabeth Minor is an adviser at Article 36, a nonprofit group based in the United Kingdom working to prevent harm from nuclear and other weapons. The name refers to Article 36 of the 1977 Additional Protocol I of the Geneva Conventions that requires states to review new weapons, means, and methods of warfare.

ACT: Women are still significantly underrepresented in our national security and arms control fields. How important is gender diversity in these areas, and what can be done to encourage women to enter these fields and reduce barriers to success?

ACT: Women are still significantly underrepresented in our national security and arms control fields. How important is gender diversity in these areas, and what can be done to encourage women to enter these fields and reduce barriers to success?