By Melissa Hanham and Seiyeon Ji

September 2017

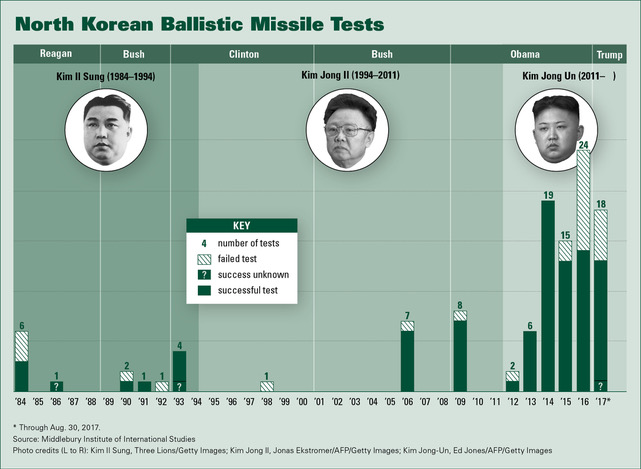

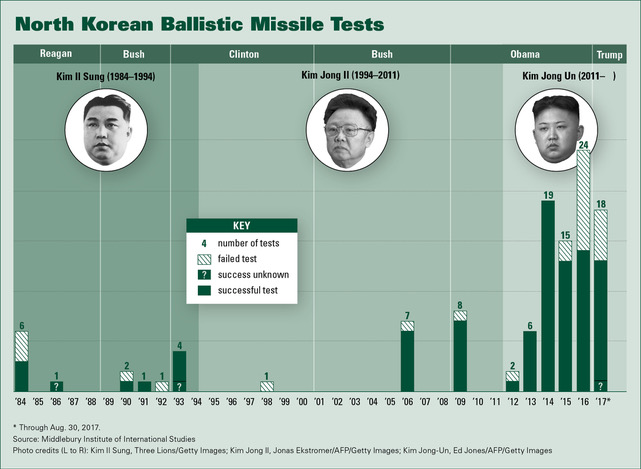

North Korea in July test-launched two intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) capable of reaching the U.S. mainland. Such long-range capability, coupled with nuclear warhead advances, has been considered a U.S. redline that could draw a U.S. military response.

A spectrum of diplomatic and military options is available to the United States and allies South Korea and Japan. The risks are significant, and the time available for diplomacy may be limited. In response to the August missile tests, the United States made a show of force, flying nuclear-capable aircraft over South Korea, and President Donald Trump on Aug. 8 threatened North Korea with “fire and fury like the world has never seen” if it continues to make threats against the United States. A hawkish minority in South Korea has renewed arguments for returning U.S. tactical nuclear weapons to their country or even for building South Korea’s own nuclear deterrent. North Korea responded to Trump’s statements by stating that leader Kim Jong Un would consider testing the Hwasong-12 intermediate-range missile toward the U.S. territory of Guam. It appears that this plan is tabled pending a favorable response from the United States.1

A spectrum of diplomatic and military options is available to the United States and allies South Korea and Japan. The risks are significant, and the time available for diplomacy may be limited. In response to the August missile tests, the United States made a show of force, flying nuclear-capable aircraft over South Korea, and President Donald Trump on Aug. 8 threatened North Korea with “fire and fury like the world has never seen” if it continues to make threats against the United States. A hawkish minority in South Korea has renewed arguments for returning U.S. tactical nuclear weapons to their country or even for building South Korea’s own nuclear deterrent. North Korea responded to Trump’s statements by stating that leader Kim Jong Un would consider testing the Hwasong-12 intermediate-range missile toward the U.S. territory of Guam. It appears that this plan is tabled pending a favorable response from the United States.1

Overwhelmingly, military and weapons of mass destruction (WMD) experts agree that there is no way to engage North Korea in a limited war that would not escalate and result in the loss of tens if not hundreds of thousands of lives on the peninsula, including American ones. “If this goes to a military solution, it’s going to be tragic on an unbelievable scale,” Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis said at a Pentagon news conference May 19, before the latest escalation in tensions.2 “So our effort is to work with the UN, work with China, work with Japan, work with South Korea to try to find a way out of this situation.”

North Korea’s rapidly advancing nuclear and missile programs pose a growing threat to the region and now the United States mainland, but the threat has not changed dramatically for South Korea, Japan, and U.S. forces based in the region. North Korea already maintains short- and intermediate-range missiles capable of carrying weapons of mass destruction or conventional high explosives, in addition to their conventional artillery and other forces. Yet, growing North Korean capabilities increase the stakes for military confrontation and reduce the time frame for diplomatic options.

North Korea’s ICBMs

On July 5 and July 29 (local time), North Korea flight-tested a Hwasong-14 ICBM. This missile is a powerful two-stage rocket that was tested at a “lofted” trajectory, meaning it went nearly four times higher than across the earth.3 The benefit of this trajectory is that the missile did not overfly Japan. If this type of missile were launched at a more gradual trajectory toward the United States, one calculation places it as likely having a range of approximately 10,400 kilometers (6,500 miles), putting cities such as Chicago at risk. Taking account of the Earth’s rotation, the range may extend to Boston and New York depending on various factors, including the weight of the missile payload.4

North Korea’s official Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) has asserted that the Hwasong-14 could carry a “large-size heavy nuclear warhead.”5 North Korea possibly is developing an even larger and heavier warhead than was previously claimed, such as a thermonuclear warhead. KCNA has made repeated claims that North Korea desires this technology, even claiming the January 2016 nuclear weapons test explosion was thermonuclear.

In addition to the Hwasong-14, at least two other ICBMs may be under development. In April, North Korea paraded several missiles systems that were purported ICBMs, including two canisterized systems. Very little can be determined about these systems through open sources because not even the missiles were visible. Although it is possible to dismiss them, these are likely design concepts that are intended for development in the future. In 2012, for example, North Korea revealed a version of the KN-08 ICBM with poor welding and other design flaws that some analysts found suspect,6 until the design became more apparent in subsequent parades.

North Korea intends to use its ICBMs to deter the United States from coming to the aid of defense treaty allies South Korea or Japan in a confrontation. Kim is gambling that the United States would not be willing to risk a major homeland city for the sake of its allies in the region. In this way, North Korea is trying to compensate for its naturally asymmetric position.7

Solid-Fueled Missiles

In February, North Korea tested a new land-based missile with a solid-fueled motor. This missile, known as the Pukguksong-2, is nearly identical to the submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) known as the Pukguksong. It is carried in a canister to maintain an optimal environment for the rocket. A solid-fueled motor offers several advantages over many North Korean missiles with liquid-fueled engines.

North Korea rotates its many road-mobile missiles constantly around its territory and in and out of caves, tunnels, and warehouses to make them difficult for adversaries to locate and track. In 2011, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates said, “North Korea now constitutes a direct threat to the United States . . . . They are developing a road-mobile ICBM. I never would have dreamed they would go to a road-mobile [missile] before testing a static ICBM. It’s a huge problem. As we’ve found out in a lot of places, finding mobile missiles is very tough.”8 To track road-mobile missiles, military satellites typically track a configuration of known vehicles that travel in convoys. A solid-fueled missile likely needs a smaller convoy because it can travel prefueled without risking the same level of corrosion as a liquid-fueled one. In addition, a prefueled rocket will shave minutes off its launch time, making them faster to use in a conflict.

North Korea revealed a new kind of transporter truck with the Pukguksong-2. This caterpillar-treaded truck is likely made at the tank factory near the launch site. This strange-looking vehicle likely appeared because North Korea can no longer procure wheeled chassis even illicitly. The treaded vehicles will present a different visual signature to the satellites tracking them. They likely are shorter range or need to be moved by rail, and they have a tighter turning radius and more difficulty on steep grades. Nonetheless, more launchers means more missiles, and they will add a dimension of difficulty to continually tracking road-mobile missiles, be they solid or liquid fueled.

North Korea’s SLBM is also solid fueled. After several disastrous explosions and even some rather ingenious fakery,9 North Korea finally had a series of successes in 2016. Like the land-based version, North Korean SLBMs are meant to increase survivability by frequently rotating. They drive up resources needed for tracking the submarines.

Warhead and Re-entry Vehicle

In March 2016, North Korea showed off what it claimed was a nuclear warhead. Set alongside an untested KN-08 missile, the message was clear: North Korea is building an ICBM to deliver a nuclear warhead to the U.S. mainland. It is not possible to confirm that the round, silver object in front of Kim in a photograph was indeed a nuclear warhead. Some features seem credible while others seem baffling. The displayed object would certainly fit on a number of North Korean missiles from short range to long range. If this is indeed a warhead, it could mean that South Korea and Japan already face a nuclear threat from North Korea. On Aug. 8, sources in the U.S. intelligence community relayed their belief that North Korea has developed a warhead capable of fitting on a missile and may have as many as 60 of them.10

Unfortunately, the only way for North Korea to prove its capability is by inviting experts to examine the weapon or by testing it on a missile in a demonstration similar to China’s 1966 CHIC-4 warhead test on a Dongfeng-2 missile. At such a tense time, no one is encouraging that option.

Unfortunately, the only way for North Korea to prove its capability is by inviting experts to examine the weapon or by testing it on a missile in a demonstration similar to China’s 1966 CHIC-4 warhead test on a Dongfeng-2 missile. At such a tense time, no one is encouraging that option.

While many continue to question North Korea’s ability to build a re-entry vehicle (RV), it is likely they have already produced and tested one. In March 2016, Pyongyang distributed photographs of a re-entry simulation in Rodong Sinmun, the official newspaper of the ruling party. Much as is the case with the warhead, it is impossible to prove that the simulation was effective with photographs alone, although the method was the same that the United States used in the 1970s.

Since the test of the intermediate-range Musudan ballistic missile in 2016, North Korea has been using a lofted trajectory to test its missiles. The purpose of this testing method may say a great deal about the crowded geography of Northeast Asia, but it also means that North Korea has been breaching the troposphere with its missiles for several months. The angle at which the missile descends is much sharper than if the missile were targeting the United States.

Therefore, the re-entry vehicle is not being tested under realistic conditions. Nonetheless, the re-entry vehicle is not one of the more complicated parts of the rocket. Its goal is to protect the warhead through the heat, pressure, and vibrations of the atmosphere. On Aug. 12, sources stated that the CIA and the U.S. Department of Defense’s National Air and Space Intelligence Center assessed that the Hwasong-14’s re-entry vehicle would likely be sufficient for a trajectory that targeted the U.S. mainland.11

The Military Option

Along the spectrum of U.S. options, a military attack on North Korea is the most dangerous. Any aggressive military strategies confirm deep-rooted North Korean suspicions and will trigger a counterreaction endangering the lives of tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of South Koreans and the approximately 23,000 U.S. troops stationed there.12 Even putting aside weapons of mass destruction, North Korea is capable of using conventional artillery to shell Seoul, which is only 35 miles from the demilitarized zone. As Mattis said on May 28,

A conflict in North Korea would be probably the worst kind of fighting in most people’s lifetimes…. The North Korean regime has hundreds of artillery cannons and rocket launchers within range of one of the most densely populated cities on Earth. . . . This regime is a threat to the region, to Japan and South Korea and in the event of war they would bring danger to China and to Russia as well. But the bottom line is it would be a catastrophic war if this turns into. . . combat if we’re not able to resolve this situation through diplomatic means.13

A preventative strike by U.S. forces, intended to be limited or not, likely would mean all-out war. North Korea knows that it has a limited number of missiles and they need to use them or lose them. Their Scud and Nodong missile drills since 2015 hint at an offensive doctrine, in which nuclear weapons must be used early in a conflict before the Kim regime or its missile and WMD sites can be destroyed.14

In 1994, when U.S. President Bill Clinton contemplated the use of force to conduct a first strike on North Korea’s Yongbyon nuclear reactor, the Pentagon concluded that a war on the peninsula would result in 1 million dead and nearly $1 trillion in economic damage.15 This estimation was made well before North Korea possessed nuclear weapons and ICBMs capable of hitting the U.S. mainland.

The human costs of any military conflict will only increase when taking into account Japanese and U.S. citizens, including U.S. soldiers and their families stationed in Japan and Guam. Within North Korea, internal displacement resulting from violence and instability means that a vast proportion of North Koreans will lack access to basic necessities and will be difficult for humanitarian agencies to reach.16 Furthermore, a Bank of Korea study predicts that 3 million refugees will attempt to cross into the South in a North Korean collapse scenario.17 A still greater number may cross the Chinese border.

Negotiating With an Enemy

On the other end of the spectrum is diplomatic engagement, which has suffered repeated failure in the past. The 1994 Agreed Framework between the United States and North Korea sought to limit Pyongyang’s nuclear activities, but broke down in 2002 due to U.S. intelligence about covert uranium-enrichment activities and the George W. Bush administration’s opposition to the accord. The subsequent six-party talks’ attempt to build a permanent peace regime in 2007 was a positive development, resulting in a denuclearization plan involving a 60-day deadline for Pyongyang to freeze its nuclear program in exchange for aid.18 Unfortunately, by the end of 2008, the North Korean regime had restarted its program and barred nuclear inspectors.19

The United States, South Korea, and Japan remain extremely skeptical of negotiating with Kim, who has been consolidating power and fortifying his cult of personality since the December 2011 death of his father, Kim Jong Il. In addition to being a reprehensible regime with profound human right violations, North Korea long has been a spoiler, holding negotiations hostage for petty reasons and failing to meet their commitments as a member of the United Nations. Yet, misunderstandings and offense have been made and received on all sides.

Although prospects for negotiations may seem dim, U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said in August that the United States could be open to talks if North Korea halts missile testing. If the United States and its allies get to negotiations, North Korea would likely seek political, economic, and security guarantees.

North Korea has left one small window open. Following the first Hwasong-14 missile test, KCNA reported that Kim “stressed that [North Korea] would neither put its nukes and ballistic rockets on the table of negotiations in any case nor flinch even an inch from the road of bolstering the nuclear force chosen by itself unless the U.S. hostile policy and nuclear threat to [North Korea] are definitely terminated.”20 Even North Korea’s August statement about launching intermediate-range missiles to splash down off the coast of Guam was left open-ended based on the behavior of the United States.

North Korea frequently demands an end to U.S.-South Korean military exercises and international sanctions, in addition to recognition that it is a nuclear-weapon state.21 North Korea would likely call for an end to the Korean War, with a peace agreement supplanting the armistice, and for additional security guarantees and aid. The United States and South Korea have largely spurned these demands, with new South Korean President Moon Jae-in repeatedly stating that reducing the joint military exercises is not an option for now and that North Korea’s nuclear freeze and a reduction of the joint military exercises cannot be linked.22

North Korea wants recognition and legitimacy in the international community that may include such things as routine diplomatic relations with the United States. Previously, there have been diplomatic exchanges between the United States and its allies and North Korea, but the United States historically has placed preconditions for talks with North Korea. For example, in 2001, the George W. Bush administration maintained that any negotiation and dialogue with North Korea would have to be preceded by “complete verification of the terms of a potential agreement.”23 The Obama administration insisted on North Korea’s commitment to denuclearization conducted in close alliance with Seoul and other members of the six-party talks.24

An additional challenge is that North Korea has no intention of giving up its nuclear weapons capabilities in the near term. North Korea’s nuclear policy has been influenced at least partially by its understanding of events in countries such as Iraq and Libya. A North Korean statement cites them as examples of “U.S. schemes to overthrow independent countries” by “weakening their military self-defense capabilities.”25 In official statements, North Korea makes clear that it will not “fall victim to the same tragic destiny” by abandoning its access to nuclear weapons.26

If North Korea will not immediately denuclearize and the United States will not accept a growing nuclear threat, the best option is to focus negotiations for a freeze, narrowing though they may be. Siegfried Hecker, a former director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory who has made seven trips to North Korea, has called for “Three Nos”: No more bombs, no more nuclear tests, and no more proliferation.27 To this might be added no additional rocket tests28 and no additional missile proliferation.

These are very tall asks for North Korea, South Korea, Japan, and the United States, and the prospects for securing what everyone wants are low. The task at hand is to incrementally find those low-hanging and, if necessary, reversible agreements that will gradually build trust. The United States was able to negotiate with the Soviet Union under much tougher circumstances.

The stakes for all sides are high, but the time for negotiation, however problematic, is now. The longer the wait, the greater North Korea’s technological capabilities will become, making diplomacy and war more difficult and dangerous.

Endnotes

1. “Kim Jong Un Inspects KPA Strategic Force Command,” KCNA, August 15, 2017.

2. U.S. Department of Defense Press Operations, “Department of Defense Press Briefing by Secretary Mattis, General Dunford and Special Envoy McGurk on the Campaign to Defeat ISIS in the Pentagon Press Briefing Room,” May 19, 2017, https://www.defense.gov/News/Transcripts/Transcript-View/Article/1188225/department-of-defense-press-briefing-by-secretary-mattis-general-dunford-and-sp/.

3. Ankit Panda, “North Korea Just Tested a Missile That Could Likely Reach Washington DC With a Nuclear Weapon,” The Diplomat, July 29, 2017, http://thediplomat.com/2017/07/north-korea-just-tested-a-missile-that-could-likely-reach-washington-dc-with-a-nuclear-weapon/.

4. David Wright, “North Korean ICBM Appears Able to Reach Major U.S. Cities,” All Things Nuclear, July 28, 2017, http://allthingsnuclear.org/dwright/new-north-korean-icbm.

5. “Kim Jong Un Guides Second Test-fire of ICBM Hwasong-14,” KCNA, July 29, 2017.

6. Markus Schiller and Robert H. Schmucker, “A Dog and Pony Show,” Arms Control Wonk, April 18, 2012, http://www.armscontrolwonk.com/files/2012/04/KN-08_Analysis_Schiller_Schmucker.pdf.

7. Ankit Panda and Vipin Narang, “North Korea’s ICBM: A New Missile and a New Era,” The Diplomat, July 7, 2017, http://thediplomat.com/2017/07/north-koreas-icbm-a-new-missile-and-a-new-era/.

8. John Barry, “The Defense Secretary’s Exit Interview,” Newsweek, June 21, 2011.

9. Catherine Dill, “Video Analysis of DPRK SLBM Footage,” Arms Control Wonk, January 12, 2016, http://www.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/1200759/video-analysis-of-dprk-slbm-footage/.

10. Joby Warrick et al., “North Korea Now Making Missile-Ready Weapons, U.S. Analysts Say,” The Washington Post, August 8, 2017. See Ankit Panda, “U.S. Intelligence: North Korea May Already Be Annually Accruing Enough Fissile Material for 12 Nuclear Weapons,” The Diplomat, August 9, 2017, http://thediplomat.com/2017/08/us-intelligence-north-korea-may-already-be-annually-accruing-enough-fissile-material-for-12-nuclear-weapons/.

11. Ankit Panda, “U.S. Intelligence: North Korea’s ICBM Reentry Vehicles Are Likely Good Enough to Hit the Continental U.S.,” The Diplomat, August 12, 2017, http://thediplomat.com/2017/08/us-intelligence-north-koreas-icbm-reentry-vehicles-are-likely-good-enough-to-hit-the-continental-us/.

12. “Counts of Active Duty and Reserve Service Members and APF Civilians by Location Country, Personnel Category, Service and Component,” Defense Manpower Data Center, February 27, 2017.

13. “War With North Korea Would Be ‘Catastrophic,’ Defense Secretary Mattis Says,” CBS News, May 28, 2017.

14. Jeffrey Lewis, “North Korea Is Practicing for Nuclear War,” Foreign Policy, March 9, 2017, http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/09/north-korea-is-practicing-for-nuclear-war/.

15. Don Oberdorfer, The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History (New York: Basic Books, 1997).

16. Bridget Coggins, “Refugees, Internal Displacement, and the Future of the Korean Peninsula,” Beyond Parallel, February 2, 2017.

17. Na Jeong-ju, “3 Million NK Refugees Expected in Crisis: BOK,” Korea Times, January 26, 2007.

18. The Six-Party Talks at a Glance,” Arms Control Association, July 2017.

19. Ibid.

20. “Kim Jong Un Supervises Test-Launch of Inter-Continental Ballistic Rocket Hwasong-14,” KCNA, July 5, 2017.

21. “DPRK’s Bolstering of Nuclear Force Hailed by Swiss Organizations,” KCNA, December 1, 2016.

22. “Moon Says Reducing Military Drills Not an Option, at Least for Now,” Yonhap News Agency, June 29, 2017.

23. Office of the Press Secretary, The White House, “Remarks by President Bush and President Kim Dae-jung of South Korea,” March 7, 2001.

24. Bruce Klingner, “Obama’s Evolving North Korean Policy,” SERI Quarterly Vol. 5, No. 3 (2012): 111.

25. Ri Hyon Do, “DPRK’s Nuclear Deterrence Is Treasured Sword of Nation.” Rodong Sinmun, June 29, 2017.

26. Kim Sung Gol, “Just Is DPRK’s Access to Nuclear Deterrent,” Rodong Sinmun, May 2, 2017.

27. Steve Fyffe, “Hecker Assesses North Korean Hydrogen Bomb Claims,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, January 7, 2016, http://thebulletin.org/hecker-assesses-north-korean-hydrogen-bomb-claims9046.

28. Both space rockets and missiles to avoid the confusion of the so-called Leap Day Deal in 2012. See Ankit Panda, “A Great Leap to Nowhere: Remembering the U.S.-North Korea ‘Leap Day’ Deal,” The Diplomat, February 29, 2016.

Melissa Hanham is a senior research associate at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies and the Mixed-Methods Evaluation, Training and Analysis (META) Lab of the Middlebury Institute of International Studies. Seiyeon Ji is a research assistant at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies.

Unfortunately, the only way for North Korea to prove its capability is by inviting experts to examine the weapon or by testing it on a missile in a demonstration similar to China’s 1966 CHIC-4 warhead test on a Dongfeng-2 missile. At such a tense time, no one is encouraging that option.

Unfortunately, the only way for North Korea to prove its capability is by inviting experts to examine the weapon or by testing it on a missile in a demonstration similar to China’s 1966 CHIC-4 warhead test on a Dongfeng-2 missile. At such a tense time, no one is encouraging that option.