"I want to tell you that your fact sheet on the [Missile Technology Control Regime] is very well done and useful for me when I have to speak on MTCR issues."

U.S. Explores INF Responses

January/February 2015

The United States is reviewing a broad range of military options to respond to a future Russian deployment of a ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM) that violates the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, a senior Defense Department official told Congress in December.

The United States is reviewing a broad range of military options to respond to a future Russian deployment of a ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM) that violates the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, a senior Defense Department official told Congress in December.

The State Department announced in July that Russia is violating its INF Treaty obligation “not to possess, produce, or flight-test” a GLCM with a range of 500 to 5,500 kilometers or “to possess or produce launchers of such missiles.” (See ACT, September 2014.)

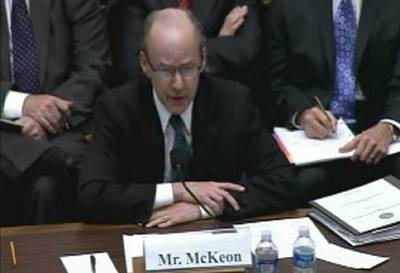

In testimony at a Dec. 10 hearing in the House of Representatives, Brian McKeon, principal deputy undersecretary of defense for policy, said a military assessment concluded “that development and deployment” of an INF-range GLCM by Russia “would pose a threat to the United States and its allies and partners.” At the hearing, held jointly by the House armed services and foreign affairs committees, Rose Gottemoeller, undersecretary of state for arms control and international security, told lawmakers that the United States has seen Russia developing a prohibited GLCM, but did not say that the missile was deployed.

If Russia does not come back into compliance with the INF Treaty, McKeon said, the United States will seek “to ensure that Russia gains no significant military advantage from its violation.” Russia denies that it is breaching the INF Treaty. The Russian Foreign Ministry said in a July 28 statement that the allegations are “baseless” and “no proof has been provided.”

McKeon said the range of military response options under consideration includes “active defenses to counter” INF-range GLCMs, “counterforce capabilities” to prevent attacks from these missiles, “and countervailing strike capabilities to enhance U.S. or allied forces.” The Defense Department is reviewing the effect these options “could have on convincing Russian leadership to return to compliance with the INF Treaty, as well as countering the capability of a Russian INF Treaty-prohibited system,” McKeon added.

McKeon did not provide details on the options, but did say that some “would be compliant with the INF Treaty” and some “would not be.” He later added that deploying U.S. GLCMs “would obviously be one option to explore.”

McKeon said that, in responding to Russia’s alleged treaty violation, the United States wants to avoid “an escalatory cycle of action and reaction.” But he warned that “Russia’s lack of meaningful engagement on this issue, if it persists, will ultimately require the United States to take actions to protect its interests and security, along with those of its allies and partners.”

One European analyst said the deployment of U.S. GLCMs in Europe is unlikely. In a Dec. 16 e-mail to Arms Control Today, Jacek Durkalec, nonproliferation and arms control project manager at the Polish Institute of International Affairs, said other options, including sea- and air-launched cruise missiles “have been seen as more realistic and less costly.” He added, however, that “if Russia would really deploy a militar[il]y significant number of GLCMs, perceptions in Europe could change.”

The INF Treaty, signed by President Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in 1987, marked the first time the two superpowers agreed to reduce their nuclear arsenals and utilize extensive on-site inspections for verification. The treaty eliminated almost 2,700 intermediate-range ballistic and cruise missiles, most of them Russian.

At the Dec. 10 hearing, Gottemoeller said the administration has “a kind of three-pronged approach” for dealing with Russia’s INF Treaty violation: diplomatic efforts to bring Russia back into compliance, exploration of potential “economic countermeasures,” and “military measures” in the event Russia’s noncompliance persists.

McKeon and Gottemoeller refused to say how much time the United States would give Russia to come back into compliance before pursuing economic and military measures. Gottemoeller noted that, in the case of Russia’s noncompliance with the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty in the 1980s, “the Reagan administration and the [George H.W.] Bush administration worked with the Soviets diplomatically for five years” before Russia returned to compliance with the treaty.

Gottemoeller led a U.S. delegation to Moscow in September for talks with Russian officials to discuss the violation. A State Department press release summarizing the meeting said that “the U.S. concerns were not assuaged at the meeting.” At the hearing, Gottemoeller and McKeon said that Russia refuses to acknowledge the existence of an illegal missile.

In a Dec. 12 statement, the Russian Foreign Ministry said the McKeon and Gottemoeller testimonies “caught our attention.” The statement lamented the U.S. “intention to exercise economic and military pressure on Russia because of its alleged non-compliance with the INF Treaty.” Referring to the downturn in U.S.-Russian relations over Ukraine, the statement said U.S. military measures “would increase tensions in a situation that is already complicated.”

The statement said that the U.S. government continues to be unable “to give an explicit wording to its claims and accusations” on Russia’s alleged INF Treaty violation and accused the United States of being in noncompliance with the treaty. The statement referred to the use of “target missiles that resemble short- and intermediate-range missiles” in U.S. missile defense tests, “armed US drones that necessarily fall under the INF Treaty definition of ground-launched cruise missiles,” and the U.S. “intention to deploy in Poland and Romania a land-based version of the MK 41 shipboard launcher for intermediate-range cruise missiles” as examples of U.S. INF Treaty violations.

The issue of how to respond to the alleged Russian noncompliance with the INF Treaty was a controversial issue on Capitol Hill last year. The House-passed fiscal year 2015 defense authorization bill included a provision requiring the Defense Department to develop a plan for the research and development of intermediate-range ballistic and cruise missiles.

The Senate Armed Services Committee’s version of the defense authorization bill contained no such provision. The final version of the bill, which was signed into law by President Barack Obama on Dec. 19, softened the House demands by requiring the Defense Department to submit a report on Russia’s alleged violation and a report describing any steps being taken or planned by the department in response.

A senior Senate staffer said in a Dec. 19 interview that the incoming Republican-led Senate would likely follow the House in advocating for a more aggressive U.S. response to Russian noncompliance.