Contact: Daryl G. Kimball, Executive Director, (202) 463-8270 x107

The 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty required the United States and the Soviet Union to eliminate and permanently forswear all of their nuclear and conventional ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges of 500 to 5,500 kilometers. The treaty marked the first time the superpowers had agreed to reduce their nuclear arsenals, eliminate an entire category of nuclear weapons, and employ extensive on-site inspections for verification. As a result of the INF Treaty, the United States and the Soviet Union destroyed a total of 2,692 short-, medium-, and intermediate-range missiles by the treaty's implementation deadline of June 1, 1991.

The United States first alleged in its July 2014 Compliance Report that Russia was in violation of its INF Treaty obligations “not to possess, produce, or flight-test” a ground-launched cruise missile having a range of 500 to 5,500 kilometers or “to possess or produce launchers of such missiles.” Subsequent State Department assessments in 2015, 2016, 2017, and 2018 repeated these allegations. In March 2017, a top U.S. official confirmed press reports that Russia had begun deploying the noncompliant missile. Russia has denied that it is in violation of the agreement and has accused the United States of being in noncompliance.

On Dec. 8, 2017, the Trump administration released an integrated strategy to counter alleged Russian violations of the treaty, including the commencement of research and development on a conventional, road-mobile, intermediate-range missile system. On Oct. 20, 2018, President Donald Trump announced his intention to “terminate” the INF Treaty, citing Russian noncompliance and concerns about China’s intermediate-range missile arsenal. On Dec. 4, 2018, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced that the United States found Russia in “material breach” of the treaty and would suspend its treaty obligations in 60 days if Russia did not return to compliance in that time. On Feb. 2, the Trump administration declared a suspension of U.S. obligations under the INF Treaty and formally announced its intention to withdraw from the treaty in six months. Shortly thereafter, Russian President Vladimir Putin also announced that Russia will be officially suspending its treaty obligations as well.

On Aug. 2, 2019, the United States formally withdrew from the INF Treaty.

Early History

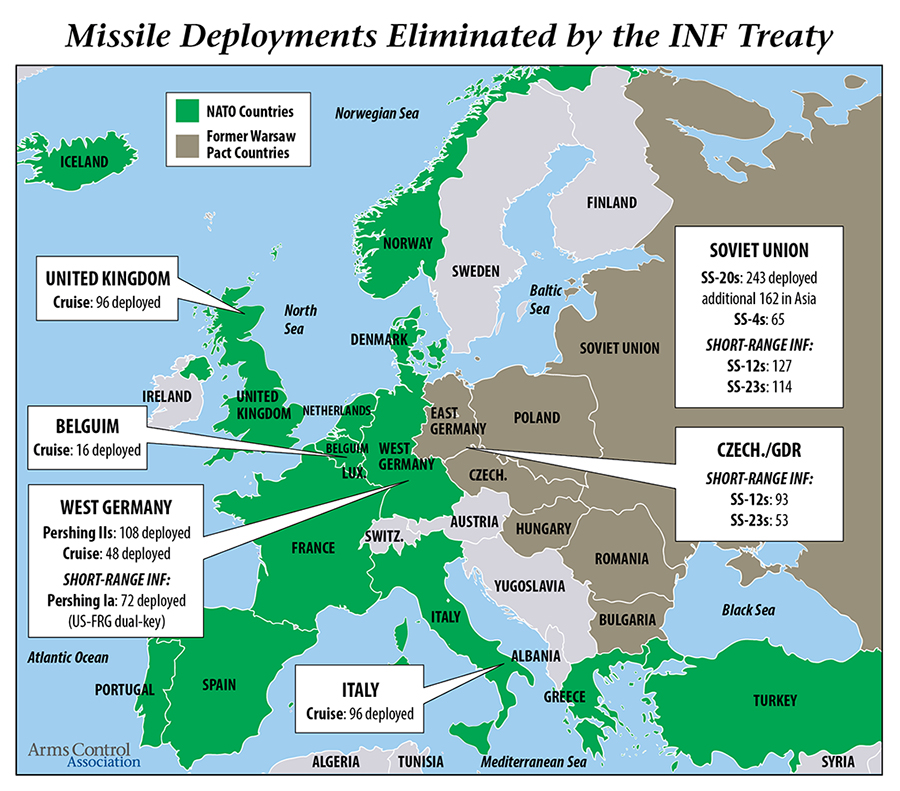

U.S. calls for the control of intermediate-range missiles emerged as a result of the Soviet Union's domestic deployment of SS-20 intermediate-range missiles in the mid-1970s. The SS-20 qualitatively improved Soviet nuclear forces in the European theater by providing a longer-range, multiple-warhead alternative to aging Soviet SS-4 and SS-5 single-warhead missiles. In 1979, NATO ministers responded to the new Soviet missile deployment with what became known as the "dual-track" strategy: a simultaneous push for arms control negotiations with the deployment of intermediate-range, nuclear-armed U.S. missiles (ground-launched cruise missiles and the Pershing II) in Europe to offset the SS-20. Negotiations, however, faltered repeatedly while U.S. missile deployments continued in the early 1980s.

INF Treaty negotiations began to show progress once Mikhail Gorbachev became the Soviet general-secretary in March 1985. In the fall of the same year, the Soviet Union put forward a plan to establish a balance between the number of SS-20 warheads and the growing number of allied intermediate-range missile warheads in Europe. The United States expressed interest in the Soviet proposal, and the scope of the negotiations expanded in 1986 to include all U.S. and Soviet intermediate-range missiles around the world. Using the momentum from these talks, President Ronald Reagan and Gorbachev began to move toward a comprehensive intermediate-range missile elimination agreement. Their efforts culminated in the signing of the INF Treaty on Dec. 8, 1987, and the treaty entered into force on June 1, 1988.

The intermediate-range missile ban originally applied only to U.S. and Soviet forces, but the treaty's membership expanded in 1991 to include the following successor states of the former Soviet Union: Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine, which had inspectable facilities on their territories at the time of the Soviet Union’s dissolution. Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan also possessed INF Treaty-range facilities (SS-23 operating bases) but forgo treaty meetings with the consent of the other states-parties.

Although active states-parties to the treaty total just five countries, several European countries have destroyed INF Treaty-range missiles since the end of the Cold War. Germany, Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic destroyed their intermediate-range missiles in the 1990s, and Slovakia dismantled all of its remaining intermediate-range missiles in October 2000 after extensive U.S. prodding. On May 31, 2002, the last possessor of intermediate-range missiles in Eastern Europe, Bulgaria, signed an agreement with the United States to destroy all of its INF Treaty-relevant missiles. Bulgaria completed the destruction five months later with U.S. funding.

States-parties' rights to conduct on-site inspections under the treaty ended on May 31, 2001, but the use of surveillance satellites for data collection continues. The INF Treaty established the Special Verification Commission (SVC) to act as an implementing body for the treaty, resolving questions of compliance and agreeing on measures to "improve [the treaty's] viability and effectiveness." Because the INF Treaty is of unlimited duration, states-parties could convene the SVC at any time.

Elimination Protocol

The INF Treaty's protocol on missile elimination named the specific types of ground-launched missiles to be destroyed and the acceptable means of doing so. Under the treaty, the United States committed to eliminate its Pershing II, Pershing IA, and Pershing IB ballistic missiles and BGM-109G cruise missiles. The Soviet Union had to destroy its SS-20, SS-4, SS-5, SS-12, and SS-23 ballistic missiles and SSC-X-4 cruise missiles. In addition, both parties were obliged to destroy all INF Treaty-related training missiles, rocket stages, launch canisters, and launchers. Most missiles were eliminated either by exploding them while they were unarmed and burning their stages or by cutting the missiles in half and severing their wings and tail sections.

Inspection and Verification Protocols

The INF Treaty's inspection protocol required states-parties to inspect and inventory each other's intermediate-range nuclear forces 30 to 90 days after the treaty's entry into force. Referred to as "baseline inspections," these exchanges laid the groundwork for future missile elimination by providing information on the size and location of U.S. and Soviet forces. Treaty provisions also allowed signatories to conduct up to 20 short-notice inspections per year at designated sites during the first three years of treaty implementation and to monitor specified missile-production facilities to guarantee that no new missiles were being produced.

The INF Treaty's verification protocol certified reductions through a combination of national technical means (i.e., satellite observation) and on-site inspections—a process by which each party could send observers to monitor the other's elimination efforts as they occurred. The protocol explicitly banned interference with photo-reconnaissance satellites, and states-parties were forbidden from concealing their missiles to impede verification activities. Both states-parties could carry out on-site inspections at each other's facilities in the United States and Soviet Union and at specified bases in Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, West Germany, and Czechoslovakia.

The INF Treaty’s Slow Demise

Since the mid-2000s, Russia has raised the possibility of withdrawing from the INF Treaty. Moscow contends that the treaty unfairly prevents it from possessing weapons that its neighbors, such as China, are developing and fielding. Russia also has suggested that the proposed U.S. deployment of strategic anti-ballistic missile systems in Europe might trigger a Russian withdrawal from the accord, presumably so Moscow can deploy missiles targeting any future U.S. anti-missile sites. Still, the United States and Russia issued an Oct. 25, 2007, statement at the United Nations General Assembly reaffirming their “support” for the treaty and calling on all other states to join them in renouncing the missiles banned by the treaty.

Reports began to emerge in 2013 and 2014 that the United States had concerns about Russia's compliance with the INF Treaty. In July 2014, the U.S. State Department found Russia to be in violation of the agreement by producing and testing an illegal ground-launched cruise missile. Russia responded in August refuting the claim. Throughout 2015 and most of 2016, U.S. Defense and State Department officials had publicly expressed skepticism that the Russian cruise missiles at issue had been deployed. But an Oct. 19, 2016, report in The New York Times cited anonymous U.S. officials who were concerned that Russia was producing more missiles than needed solely for flight testing, which increased fears that Moscow was on the verge of deploying the missile. By Feb. 14, 2017, The New York Times cited U.S. officials declaring that Russia had deployed an operational unit of the treaty-noncompliant cruise missile now known as the SSC-8. On March 8, 2017, General Paul Selva, the vice chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, confirmed press reports that Russia had deployed a ground-launched cruise missile that “violates the spirit and intent” of the INF Treaty.

On Dec. 8, 2017 the Trump administration announced a strategy to respond to alleged Russian violations, which comprised of three elements: diplomacy, including through the Special Verification Commission, research and development on a new conventional ground-launched cruise missile, and punitive economic measures against companies believed to be involved in the development of the missile.

The State Department’s 2018 annual assessment of Russian compliance with key arms control agreements alleged Russian noncompliance with the INF Treaty and listed details on the steps Washington has taken to resolve the dispute, including convening a session of the SVC and providing Moscow with further information on the violation.

The report said the missile in dispute is distinct from two other Russian missile systems, the R-500/SSC-7 Iskander GLCM and the RS-26 ballistic missile. The R-500 has a Russian-declared range below the 500-kilometer INF Treaty cutoff, and Russia identifies the RS-26 as an intercontinental ballistic missile treated in accordance with the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START). The report also appears to suggest that the launcher for the allegedly noncompliant missile is different from the launcher for the Iskander. In late 2017, the United States for the first time revealed both the U.S. name for the missile of concern, the SSC-8, and the apparent Russian designation, the 9M729.

Russia denied that it breached the agreement and has raised its own concerns about Washington’s compliance. Moscow charges that the United States is placing a missile defense launch system in Europe that can also be used to fire cruise missiles, using targets for missile defense tests with similar characteristics to INF Treaty-prohibited intermediate-range missiles, and making armed drones that are equivalent to ground-launched cruise missiles.

Congress responded to the allegations of Russian noncompliance by approving more assertive military and economic countermeasures. The fiscal year 2018 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) authorized funds for the Defense Department to develop a conventional, road-mobile, ground-launched cruise missile that, if tested, would violate the treaty. The fiscal year 2019 NDAA also included provisions on the treaty. Section 1243 stated that no later than Jan. 15, 2019, the president would submit to Congress a determination on whether Russia is “in material breach” of its INF Treaty obligations and whether the “prohibitions set forth in Article VI of the INF Treaty remain binding on the United States.” Section 1244 expressed the sense of Congress that in light of Russia’s violation of the treaty, that the United States is “legally entitled to suspend the operation of the INF Treaty in whole or in part” as long as Russia is in material breach. For fiscal year 2020, the Defense Department requested nearly $100 million to develop three new missile systems that exceed the range limits of the treaty.

Then, on Oct. 20, 2018, President Trump announce that he would “terminate” the INF Treaty in response to the long-running dispute over Russian noncompliance with the agreement, as well as citing concerns about China’s unconstrained arsenal of INF Treaty-range missiles. Trump’s announcement seemed to take NATO allies by surprise, with many expressing concern about the president's plan.

After repeatedly denying the existence of the 9M729 cruise missile, Russia has since acknowledged the missile but denied that the missile was tested or is able to fly at an INF Treaty-range.

On Nov. 30, U.S. Director of National Intelligence Daniel Coats provided further details on the Russian treaty violation. Coats revealed that the United States believes Russia cheated by conducting legally allowable tests of the 9M729, such as testing the missile at over 500 km from a fixed launcher (allowed if the missile is to be deployed by air or sea), as well as testing the same missile from a mobile launcher at a range under 500 km. Coats noted that “by putting the two types of tests together,” Russia was able to develop an intermediate-range missile that could be launched from a “ground-mobile platform” in violation of the treaty.

On Dec. 4, 2018 Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced that the United States found Russia in “material breach” of the treaty and would suspend its treaty obligations in 60 days if Russia did not return to compliance in that time. Though NATO allies in a Dec. 4 statement expressed for the first time the conclusion that Russia had violated the INF Treaty, the statement notably did not comment on Pompeo's ultimatum.

Russian President Vladimir Putin responded Dec. 5 by noting that Russia would respond “accordingly” to U.S. withdrawal from the treaty, and the chief of staff of the Russian military General Valery Gerasimov noted that U.S. missile sites on allied territory could become “targets of subsequent military exchanges." On Dec. 14, Reuters reported that Russian foreign ministry official Vladimir Yermakov was cited by RIA news agency as saying that Russia was ready to discuss mutual inspections with the United States in order to salvage the treaty. The United States and Russia met three more times after this, first in January in Geneva, on the sidelines of a P5 meeting in Beijing, and again in Geneva in July—all times to no new result.

On Feb. 2, 2019 President Trump and Secretary of State Pompeo announced that the United States suspended its obligations under the INF Treaty and would withdraw from the treaty in six months if Russia did not return to compliance. Shortly thereafter, Russian President Vladimir Putin also announced that Russia will be officially suspending its treaty obligations.

On March 4, 2019 Russian President Vladimir Putin signed a decree officially ending Russia's participation in the treaty.

Six months later, on Aug. 2, 2019, the United States formally withdrew from the INF Treaty. In a statement, Secretary Pompeo said, “With the full support of our NATO Allies, the United States has determined Russia to be in material breach of the treaty, and has subsequently suspended our obligations under the treaty.” He declared that “Russia is solely responsible for the treaty’s demise.” A day later, U.S. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper said that he was in favor of deploying conventional ground-launched, intermediate-range missiles in Asia “sooner rather than later.”