"The Arms Control Association’s work is an important resource to legislators and policymakers when contemplating a new policy direction or decision."

What the Russian Public Thinks About the Use of Nuclear Weapons

October 2024

By Michal Smetana and Michal Onderco

In the years since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Kremlin’s nuclear saber-rattling has become almost routine. President Vladimir Putin frequently highlights the power of Russia’s massive nuclear arsenal in his public speeches, while other Russian politicians and foreign policy experts do not shy away from discussing the possibility of nuclear strikes against Ukraine’s Western backers.1 Many NATO countries have taken the threat of nuclear escalation very seriously since the war began, and according to new reporting, the U.S. administration believed that Russia was on the brink of using a tactical nuclear weapon against Ukraine in the second half of 2022.2

Yet, in one of his recent speeches, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy downplayed the threat of Russian nuclear use, arguing that the Russian government would not break the decades-old “nuclear taboo” for fear of losing broad societal support.3 If this argument holds, it would suggest that nuclear employment represents a true redline for the Russian public beyond which the Kremlin can no longer count on popular approval for its foreign policy adventurism. Is there any ground for the claim that a majority of the Russian public would oppose nuclear use, especially if doing so would increase Russian chances for a swift victory in Ukraine or even prevent Russia from losing the war?

In June 2024, we conducted a unique survey experiment in Russia to find out.4 In contrast to vague questions in more traditional public opinion polls, participants in our experiment were provided with very specific hypothetical scenarios in which the Russian government considered nuclear strikes against NATO or Ukraine as a way of averting military defeat.5

We worked together with a local, independent nongovernmental organization in Russia, the Levada Center, to conduct our experiment on a large representative sample of the Russian population. Levada is a trusted partner for numerous Western organizations and media to conduct public opinion research in Russia. Our experiment was embedded in Levada’s monthly omnibus survey, which is a Russia-wide poll, with participants coming from large cities such as Moscow and Saint Petersburg and small rural settlements in Siberia and the Far East. In total, we conducted our study on a representative sample of 1,600 Russian citizens aged 18 years or older from 137 settlements in 50 regions of the Russian Federation.6

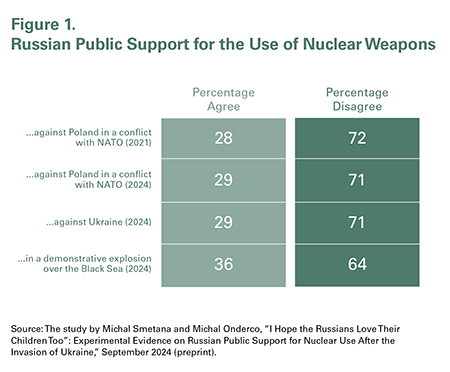

The results have been fascinating in many ways (fig. 1). A majority of Russians (71 percent) disagreed with a limited nuclear strike against a NATO military base in Poland, even when not doing so would result in the Russian army being defeated in a fictional conflict in the Baltics. Comparing these numbers to the results of our 2021 study, we can conclude that the percentage of Russians who would agree with their government’s decision to conduct a nuclear strike against NATO—28 percent in 2021 and 29 percent in 2024—has changed little over the past three years.7 This finding suggests that the Russian war against Ukraine and the Kremlin’s nuclear saber-rattling have not had a dramatic impact on the widely shared public aversion to the idea of a nuclear escalation.8

The results also show that roughly the same proportion of Russian citizens who disagreed with nuclear weapons use against NATO (72 percent) rejected a nuclear strike against a military target in Ukraine, despite the fact that Ukraine is not covered by NATO’s nuclear umbrella. It suggests that the Russian aversion to nuclear escalation is not merely due to a concern about nuclear retaliation by NATO allies. Not using a nuclear weapon in our scenario came with serious strategic consequences, specifically, the loss of Crimea, the Ukrainian region whose illegal annexation by Russia in 2014 is supported by a majority of the Russian public.9

Somewhat disconcerting was the slightly higher public support for a demonstrative nuclear explosion over the Black Sea (36 percent). A Russian expert recently proposed such a nuclear demonstration “to show the seriousness of Russia’s intentions and convince our opponents of Moscow’s resolve to escalate.”10 Yet, even in this less escalatory scenario, almost two-thirds of Russians (64 percent) disagreed with pressing the nuclear button.

It is fair to ask whether Russian leaders even care what the public thinks. After all, Putin’s regime is a repressive autocracy that has become even more so since the start of the full-blown invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.11 Yet, for Putin’s regime, what people think matters. The Kremlin has been highly sensitive to any signs of fluctuations in public opinion, and frequent public polling has been a standard practice of this regime.12 Overall, many experts on Russian politics agree that the Russian government does not only shape public preferences in foreign policy, but it also is partially responsive to public sentiments in this area.13 A case in point may be Putin’s hesitation to order a military mobilization in the first year of the war, likely postponed mainly due to concerns about public backlash.14

Interestingly, the Russian public generally tends to have a positive relationship with the country’s nuclear arsenal and sees it as a source of Russian power and status.15 This standing is due in no small part to consistent messaging in Russia, which has portrayed the nation’s enormous nuclear arsenal as prideworthy. Putin’s regime has invested heavily in showing off Russia’s newest nuclear missiles and using them as props during military parades.

The domestic nuclear messaging has continued after the invasion. Russia’s nuclear rhetoric during the first 16 months of the war was often directed at the Russian public, as well as at Western audiences. Although official Kremlin messaging has been somewhat careful, opinions peddled by Moscow’s pundits in popular outlets and various magazines and on TV have been anything but. This more hawkish narrative has been reinforced and strengthened by a religious undertone, which included the blessing of nuclear missiles by the Russian Orthodox Church.16

The amount of attention that the nuclear saber-rattling gets on Russian public TV, from which most Russians get their news, underscores that the Russian regime still cares about public views on the nuclear arsenal. Far from being irrelevant, public opinion matters for Putin’s Russia. The results of our survey indicate that, despite significant public propaganda by the Russian government and its surrogates, the Russian public thus far has not become more enthusiastic about the prospect of using nuclear weapons to influence the course of the war in Ukraine. This finding alone might cause some disappointment in the Kremlin.

For Western policymakers, these findings offer a rare glimpse of hope. The Kremlin’s coercive messaging in the war in Ukraine has shown the limited capacity of the Russian leadership to learn from the failures of its nuclear threats.17 The results of the study indicate that domestic audiences are not more eager to consider nuclear options, even in the face of potential Russian military failure and persistent domestic messaging. This finding underscores that ordinary Russians understand the limits of nuclear coercion well and their belief in the nuclear taboo appears rather firm. The lack of change in Russian public attitudes toward the use of nuclear weapons since the invasion of Ukraine underscores how difficult it might be to shift public views and how strong the atomic aversion among the Russian public is.

For Western governments, the most fruitful strategy appears to be to continue their persistent messaging rejecting the legitimacy of the Kremlin’s nuclear threats. It makes sense to continue underscoring that any use of nuclear weapons would lead to a forceful response by NATO and to material, political, and moral consequences for Russia. The Russian public subconsciously understands this message, which needs to be firmly reinforced.

ENDNOTES

1. “Putin Says Russia Will Develop Its Nuclear Arsenal to Preserve Global Balance of Power,” Reuters, June 21, 2024; “Nukes! Medvedev Again Threatens West With Nuclear Escalation,” Kyiv Post, June 1, 2024, https://www.kyivpost.com/post/33622; Sergei A. Karaganov, “A Difficult but Necessary Decision,” Russia in Global Affairs, June 13, 2023, https://eng.globalaffairs.ru/articles/a-difficult-but-necessary-decision/.

2. Jim Sciutto, “Exclusive: U.S. Prepared ‘Rigorously’ for Potential Russian Nuclear Strike in Ukraine in Late 2022, Officials Say,” CNN, March 9, 2024, https://edition.cnn.com/2024/03/09/politics/us-prepared-rigorously-potential-russian-nuclear-strike-ukraine/index.html.

3. Nina Tannewald, “Is Using Nuclear Weapons Still Taboo?” Foreign Policy, July 1, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/07/01/nuclear-war-taboo-arms-control-russia-ukraine-deterrence/; Kateryna Shkarlat, “Zelenskyy Outlines What Is Restraining Putin From Nuclear Strike on Ukraine,” RBC-Ukraine, May 3, 2023, https://newsukraine.rbc.ua/news/zelenskyy-outlines-what-is-restraining-putin-1714764161.html.

4. For full results of our experiment and a detailed statistical analysis, see Michal Smetana and Michal Onderco, “I Hope the Russians Love Their Children Too”: Experimental Evidence on Russian Public Support for Nuclear Use After the Invasion of Ukraine,” September 2024, https://ssrn.com/abstract=4906365 (preprint).

5. “On the Possibility of Using Nuclear Weapons in the Ukrainian Conflict,” Levada Center, June 21, 2023, https://www.levada.ru/en/2023/06/21/on-the-possibility-of-using-nuclear-weapons-in-the-ukrainian-conflict/.

6. For more information, see “Levada Omnibus Survey,” Levada Center, n.d., https://www.levada.ru/en/methods/omnibus/ (accessed September 20, 2024).

7. See Michal Smetana and Michal Onderco, “From Moscow With a Mushroom Cloud? Russian Public Attitudes to the Use of Nuclear Weapons in a Conflict With NATO,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 67, Nos. 2-3 (2023): 183-209.

8. Heather Williams et al., “Deter and Divide: Russia’s Nuclear Rhetoric and Escalation Risks in Ukraine,” CSIS Project on Nuclear Issues, 2024, https://features.csis.org/deter-and-divide-russia-nuclear-rhetoric/.

9. “Most Russians Support Annexation of Crimea - Poll,” The Moscow Times, April 26, 2021, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2021/04/26/most-russians-support-annexation-of-crimea-poll-a73741/.

10. Dmitriy Suslov, “Пора подумать о демонстрационном ядерном взрыве” [It’s time to think about a demonstration nuclear explosion], Profil, May 29, 2024, https://profile.ru/abroad/pora-podumat-o-demonstracionnom-yadernom-vzryve-1520096/.

11. “Russia: New Heights on Repression,” Human Rights Watch, January 11, 2024, https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/01/11/russia-new-heights-repression.

12. Olga Oliker et al., “Russian Foreign Policy in Historical and Current Context: A Reassessment,” Rand Corp., September 12, 2024, https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE144.html.

13. Anna Efimova and Denis Strebkov, “Linking Public Opinion and Foreign Policy in Russia,” The International Spectator, Vol. 55, No. 1 (2020): 93-111.

14. Oleg Sukhov, “Putin Lacks Troops in Ukraine but Fears Mobilization in Russia,” Kyiv Independent, July 5, 2022, https://kyivindependent.com/putin-lacks-troops-in-ukraine-but-fears-mobilization-in-russia/.

15. Larisa Deriglazova and Nina Rozhanovskaya, “Building Nuclear Consensus in Contemporary Russia: Factors and Perceptions,” in Nuclear Russia: International and Domestic Agendas, ed. Andrey Pavlov and Larisa Deriglazova (Tomsk: Tomsk University Press, 2020), 131-162.

16. Mansur Mirovalev, “‘God of War’: Russian Orthodox Church Stands by Putin, but at What Cost?” Al Jazeera, February 9, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/2/9/far-from-harmless-patriarch-kirill-backs-putins-war-but-at-what-cost.

17. Anna Clara Arndt, Liviu Horovitz, and Michal Onderco, “Russia’s Failed Nuclear Coercion Against Ukraine,” The Washington Quarterly, Vol. 46, No. 3 (2023): 167-184.

Michal Smetana is an associate professor at the Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University, and director of the Peace Research Center in Prague. Michal Onderco is a professor of international relations in the Department of Public Administration and Sociology at Erasmus University in Rotterdam.