Out of the Shadows: The Implications of Iran’s Recent Duel With Israel

June 2024

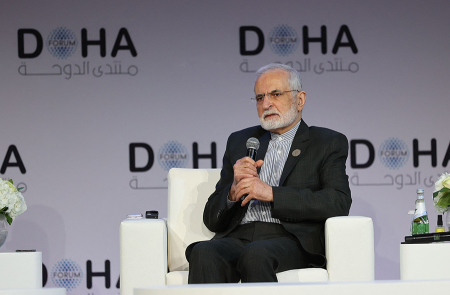

A Middle Eastern region already on edge over the war between Israel and Hamas in Gaza faced another escalation of violence on April 1 when Israel struck the Iranian embassy complex in Damascus, killing 16 people, including eight officers of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Two weeks later, Iran responded by attacking Israel from Iranian territory for the first time with at least 300 drones and missiles. An Israeli base in the Negev desert sustained light damage, and a 7-year-old girl was seriously wounded, The New York Times reported, but more serious damage was averted because the United States and its allies helped Israel intercept the Iranian onslaught. Israel’s retaliation on April 18 was more limited than expected, but as the two countries had brought their long shadow war into the open, many people were fearful of what might come next. Arms Control Today gathered three experts on May 24 to discuss the implications of the Iranian-Israeli faceoff for the region. Nicole Grajewski is a fellow with the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Sina Toossi is a senior fellow at the Center for International Policy, and Ali Vaez is senior adviser at the International Crisis Group and director of the group’s Iran Project. This transcript has been edited for clarity and length.

Arms Control Today: Why did the shooting war between Iran and Israel not explode into a wider war? What does this escalation mean to regional stability and the regional balance of power?

Ali Vaez: I think there are two main reasons why the exchange of fire between Iran and Israel did not result in an all-out war. The first is that none of the key stakeholders—Iran, the United States, and I would even say the Israeli government—had an interest in this turning into a regional conflagration. We know the United States already has its hands full with the war in Ukraine, with the war in Gaza, with concerns about China’s designs over Taiwan and it’s an election year, of course. In Iran, there is deep socioeconomic discontent, and the country just does not have the bandwidth to go through a conflict with much stronger adversaries such as Israel and the United States. Finally, Israel already is bogged down in Gaza and has serious concerns with Hezbollah on its northern border. I think this reluctance on all sides was one of the key reasons that they could manage the repercussions of an Israeli attack on the Iranian consulate on April 1, the Iranian retaliation on April 14, and Israel’s pinpoint attack on April 18.

The second reason is that there was a lot of behind-the-scenes diplomacy aimed at trying to minimize the risks of tensions spiraling out of control. We know that the United States was surprised by Israel’s attack on the Iranian consulate in Damascus and tried to take distance from it. We know that, since the attack, not just the United States but also Iran’s neighbors and European governments reached out to Iran, urging a restrained or at least a limited response. That is why, I think, the Iranian response was calibrated and telegraphed in advance. Finally, once the response took place, attention shifted toward trying to hold Israel back. That

is why Israeli response was quite limited in nature.

Sina Toossi: I think neither side wanted war. The United States certainly didn’t want war. I would argue that Israel’s attack on the Damascus consulate ended up being a miscalculation. The Israelis did not think that Iran would launch a direct attack on Israel. The Iranians in that attack sought to establish a new redline. Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, characterized the attack on the Damascus consulate as an attack on Iranian soil and one that would be directly responded to by Iranians, and we saw that the attack was telegraphed 10 days in advance.

According to what the Iranians say, they didn’t use their best missiles and armaments. It started with these more slow-moving drones, which took five hours to get there, followed by ballistic missiles. But their goal was to establish deterrence. Israel, until now, has had deterrence domination in the region. We’ve seen years of Israel, pretty much with impunity, attacking Iranian-aligned targets in Syria, acts of sabotage and subversion within Iran, assassinations, and Iran has more or less been restrained or unable to respond or had this policy of so-called strategic patience. But this [attack] was an example of the Iranians explicitly trying to establish a new deterrence equation; that’s how the IRGC chief characterized it.

In terms of whether they’ve successfully achieved that, Israeli officials immediately claimed that 99 percent of Iranian missiles were intercepted. I think that has to be taken with a certain amount of salt. Regardless of what [Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin] Netanyahu’s personal ambitions might be, I think that U.S. pressure pushed the Israelis towards restraint. I think they had an incentive to downplay the impact of the Iranian strike. Regardless, U.S. officials told ABC News that around 10 Iranian missiles hit some of these Israeli facilities that were responsible for the attack on the Damascus consulate and airbase. There are also videos out there that show some impacts, at least. I think the Iranians did manage, on a minor level and without an intention of this escalating into a regional war, to penetrate the Iron Dome and David’s Sling systems, this kind of multilayered air defense that Israel has. I think that is partly why this has not escalated, that in addition to all the regional diplomacy and the personal stakes for all these countries, that this deterrence equation is changing. For now, temporarily at least, I would again argue that Israel’s very measured response, compared to what they’ve done in the past, which was much more brazen, much more aggressive in what they’ve claimed to do and what they’ve seemingly done, this one was much smaller by all accounts. The Iranians pretty much claimed that nothing really happened. Again, part of that is a desire not to escalate, and a new deterrence has been salvaged from the Iranian side, but that is tenuous. I think the direction of the Gaza war, and especially with Lebanon, will be very decisive.

ACT: In addition to adding anything to that last question, what does this Iranian-Israeli escalation mean to regional stability and the regional balance of power?

Nicole Grajewski: I think when we’re thinking about regional stability and the balance of power, this kind of acrimonious relationship between Iran and Israel has really shaped the broader regional order, and that’s likely to continue. One thing about the attacks that was so remarkable was that this was an escalation outside of the traditional area where Iran and Israel usually have engaged. Typically, Syria and parts of Iraq or Lebanon are where the main tension between Israel and Iran has played out. In December, there was an assassination of a higher-level IRGC general and then of course the consulate attack [in Damascus]. There’s still ongoing hostilities between Iran and Israel within Syria or within Iraq. I believe some of the Iranian proxies claimed that they were targeting Israel from Iraq a few days ago. So, this has not really faded away.

One thing about the April 14 attack on Israel that is less discussed is just the precision of Iranian weapons and munitions was actually very bad. Some of the missiles were not intercepted because of the lack of precision of Iranian ballistic missiles, which deviated from their targets. The strikes, although overwhelming, showed some of Iran’s weaknesses when it comes to precision targeting and accuracy. In contrast, the Israeli strike on Iran’s S-300 pinpointed the missile defense system’s battery down to a T. This shows a weakness when it comes to Iran’s capabilities.

But on the regional balance of power, I think that Iran restored deterrence, and we see a return to kind of the status quo. Obviously, Israel is bogged down in Gaza, but there are discussions ongoing still with Israel and the Saudis on potential normalization. Iran has normalized relations with the Saudis. But there hasn’t been a major disruption in terms of military or coercive power that has radically shifted the balance of power since the events.

ACT: The recent deaths of Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi and Foreign Minister Hossein Amirabdollahian in a helicopter crash introduced a new element of instability. What does Raisi’s death mean to politics in Iran and the region?

Toossi: I don’t expect much change in the near term. Foreign policy in Iran is implemented by the presidential administration, but devising it is more with the supreme leader’s office and more through a consensus approach in the Supreme National Security Council. As for the driver of Iran’s policies in the region, I don’t think any of those factors are going to change in the near term. Iran is still trying to engage in this proxy war with Israel, with the United States, but we’ll have to see what happens in Iran’s upcoming presidential election. The calculations for Iranians are contradictory in a way. There are opposing forces; and they’re having this increased legitimacy crisis in the past five years, where the turnout in the past presidential election and the parliamentary election was at historic lows; and there have been these protests over the death in custody of Mahsa Amini.

On the other hand, all the factors that contributed to Raisi’s rise and to the main center of power in Iran engineering the 2021 election to ensure his victory are still largely in place. I would argue it was largely about the conservative factions most fiercely loyal to Khamenei trying to maximize their influence over the system and Khamenei’s eventual succession. They want to have all these institutions aligned with them for when Khamenei passes; he’s obviously at a very advanced age. I think that logic still applies. If they allowed a Mohammad Javad Zarif [a moderate former foreign minister] to run now for president to boost public enthusiasm and potential turnout, that to me is still in contradiction with what seemingly has been their agenda all along. But I think they ultimately have to balance these forces. We’ll see who the Guardian Council approves as presidential candidates. If it does approve a more prominent moderate or reformist figure who could potentially generate more public enthusiasm, then that could potentially have implications for Iran’s foreign policy. But I think that is unlikely. Most likely, they’ll look for someone like Raisi, someone more passive and docile who’s more in line with what Khamenei wants.

ACT: Do you think that there’ll be any real change?

Vaez: It appears unlikely. At this moment in its history, the Islamic Republic seems to be primarily focused on ideological and political conformity at the top rather than legitimacy from below. In that sense, it is very likely, as has been the case with the past three elections—one presidential and two parliamentary—that the Guardian Council is only going to allow a very limited number of candidates that are in line with the supreme leader’s vision for the future of the Islamic Republic to participate. Even if there are reformist or pragmatist candidates, those would be rather safe bets who would not be able to garner sufficient support from the electorate. For its part, the electorate is experiencing political apathy. Two weeks ago, there were run-up parliamentary elections; and only 8 percent of Tehranis in the Iranian capital went to the polls, which was quite telling about how the institution of elections has been emptied out of any meaning for bringing about viable change and reforms to the political system.

Having said this, without any doubt, the upcoming election is going to splinter the conservative camp and deepen the rivalries as they jockey for the position of president, with the succession of the supreme leader looming large on the horizon. We don’t know this for sure, but if President Raisi was being groomed for the top job, then it’s back to the drawing board because it will be hard to find someone who would have all of the characteristics that Raisi had, in the sense that he’s a cleric subservient to the supreme leader with a long track record of proven loyalty and a relative consensus figure within the conservative camp. Most of the names that are out there right now [as alternative candidates] are actually laypeople, not clerics. It wouldn’t be hard, however, to find someone who would be a figurehead for succeeding the supreme leader, someone who would no longer be supreme. Earlier this week, a 92-year-old ayatollah was selected as the head of the Assembly of Experts, which nominally is in charge of selecting the next supreme leader. He can barely speak. People with that kind of characteristic are not difficult to find, but not all the characteristics that I mentioned in one person.

In terms of regional and foreign policy, I do agree with what Sina said. There’s just one consideration: this unexpected, sudden demise of the president and his foreign minister means that the country, at least for the next few weeks as it goes through a condensed electoral process and then will have to get confirmation for a new cabinet, would be inward-looking. That means that it would not have enough bandwidth to engage in any kind of serious discussions, whether that’s with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) or in direct talks with the United States that we know recently took place in Oman.

ACT: There has been an uptick in Iranian rhetoric about its nuclear weapons capability in recent weeks. Kamal Kharrazi, adviser to Iran’s supreme leader and a former foreign minister, for one, has said an Israeli strike on an Iranian nuclear facility could provoke Iran to build a weapon. Why is this rhetoric churning now? What are the implications?

Grajewski: The increase in rhetoric about this looming threat of weaponization, I think that’s a conscious choice, and in a sense that was part of this whole deterrence strategy that you’ve seen out of Iran. Obviously Iran, if it wanted to, has the ability to reconstitute some of its former activities prior to 2003, but we’ve not seen that decision made. Iran’s political elites have not made the decision to weaponize. The rhetoric has mostly been used as kind of a deterrence tactic or part of this larger strategy of leveraging Iran’s status as a threshold state, meaning that in many ways Iran has the fissile material and the experience to potentially break out, although it has not made that decision. When you see the rhetoric coming out from high-level officials, it seems to be almost coordinated. There are statements from Ali Akbar Salehi, the former head of the atomic energy organization, that would imply that. Then you have the supreme leader’s advisers making similar statements on multiple occasions within a few days. Other people have different interpretations, but it seems to me that there is an understanding that the West is paying attention to that and that this is an issue that is more directed outwardly, then there’s one that is directed inwardly toward its populations as a way to normalize a nuclear program to the Iranian population. In my view, the rhetoric is mostly directed outwardly in an effort to leverage Iran’s threshold nuclear status.

Toossi: I think there’s definitely this element of using warnings about potential weaponization as leverage, also with an interest for some kind of negotiation, such as Kharrazi last week explicitly tying the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) nuclear deal and the desire for negotiations. But both Zarif and a senior IRGC commander, Ahmad Haghtalab, who is in charge of the protection of nuclear facilities, also tied their warnings about Iran potentially changing its nuclear doctrine to an Israeli attack on Iran. I think that’s also an important context where we are in this unprecedented situation where Iran ultimately did launch a direct attack on Israel. We were talking about whether deterrence is established early or not, but I also read into that rhetoric a kind of warning that if this situation with Israel escalates, that could factor into Iran’s nuclear calculations. We’ve seen that, for example, Israeli officials are seemingly primed to eventually attack Lebanon. It’s unclear when that would happen, but there are a lot of indications of that. In the case of a major regional escalation with Hezbollah, I think potentially the Iranians are also putting that option of potential weaponization on the table.

Vaez: What worries me the most is that the discourse that was taboo in Iran is becoming gradually normalized, and that has happened in parallel with a significant growth in Iran’s nuclear capabilities. That combination, even if in the short run, doesn’t imply an immediate decision to cross the Rubicon and develop nuclear weapons, but in the medium term could take the country in that direction especially if Iran comes to the conclusion that it cannot use its nuclear capabilities as leverage at the negotiating table to get out from under U.S. sanctions. This could happen if the United States fails to demonstrate that it is willing and able to provide effective and sustainable sanctions relief to Iran or if there is an administration in place that does not have an interest in a mutually beneficial agreement with the Iranian regime. This could well happen with a second Trump administration.

The second thing that could compel Iran to move in that direction is a change in its threat perception. So far, tensions in the region have remained relatively contained, but if indeed Israel engages in a conflict with Hezbollah that could result in the significant weakening of Hezbollah’s capabilities, then Iran would feel more insecure. The pinpoint attack that Israel conducted on April 18 also was a reminder to the Iranians of how vulnerable they are, especially in terms of conventional defensive military capabilities. So, if Iran’s regional deterrence is diminished, it might decide to use its nuclear capabilities as the ultimate deterrent. I think we should take this seriously, but I agree that in the immediate run, what this implies is that Iran does not want to become a Cuba and live under U.S. sanctions in perpetuity and so it is going to put pressure on the West to engage in nuclear diplomacy in a serious way.

ACT: Do you think that Iran is still interested in a nuclear deal that rolls back its program, or do you think that it sees a strategic benefit in maintaining some sort of threshold status?

Vaez: I no longer believe that a deal that would be as good as the JCPOA is achievable. I believe Iran always wanted to arrive at a point where it is right now, which thanks to President [Donald] Trump’s unwise decision [to withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal] in 2018, it has been able to get to. I don’t think there is any going back from it, especially because of a high degree of cynicism within the Iranian political elite about the prospects of getting viable sanctions relief. If you look at the realities on the ground, almost everything that led to the 2015 nuclear deal no longer applies. The P5+1 [coalition of the permanent members of the UN Security Council and Germany] no longer exists because of tensions between Russia and China on the one hand and the West on the other. The core bargain of the JCPOA is no longer relevant because of Iran’s irreversible nuclear advancement and because of the West’s proven inability to provide sanctions relief. The compartmentalization of this agreement with Iran, which was one of the reasons that the JCPOA became possible, is no longer realistic, given that Iran is, from the U.S. perspective, on the wrong side of the war in Ukraine and Gaza and of course has stepped up its repression against its own people. So, I think what the Iranians are seeking is economic incentives in return for preserving the status quo and staying a threshold state, which as you can imagine is a very unattractive prospect for the West. This is why, even in the best case scenario post-U.S. presidential elections, it is going to be excruciatingly difficult to find a mutually acceptable formula.

ACT: Are you saying that if there is a deal at any point going forward, it would not just deal with the nuclear issues, but with political issues as well?

Vaez: Yes, if you look at the deescalatory understanding that the United States and Iran had in the summer of 2023, it is quite telling because, for the first time, this didn’t include just nuclear measures but regional and ballistic missile elements as well. Iran had committed, from what we know, not to transfer ballistic missiles to Russia and not to target U.S. forces in Iraq and Syria in addition to agreeing to freeze the size of the stockpile at [uranium enriched to] 60 percent [U-235] and not installing additional advance centrifuges. That is the model that would have to be applied in the future as well. I have a hard time imagining that the West would be willing and able to reward Iran with sanctions relief if indeed there are Iranian activities that would then make justifying that economic reprieve too politically costly for Western leaders.

ACT: How do the rest of you see the prospect of diplomacy?

Toossi: I think that’s a very notable aspect of the deescalation agreement, that the Iranians agreed to tie it to these regional actions that they do and attacks on U.S. forces. From my understanding, that’s something they were averse to do in the past, in 2015. At least in my view, it kind of creates a precedent if there is a new deal. I agree that the JCPOA doesn’t work for any side anymore and that a new deal would have to be something bigger and these regional disputes would have to be included. But whether that’s viable or not, I’m inclined to agree with Ali, and I’m very pessimistic. I think, in general, the overall trajectory in Iran is, we don’t care what the West wants, we’re going to continue these relationships with our neighbors, with China, with Russia, kind of bet on that horse. Raisi’s funeral is testament to this fact that Iran’s ties have improved with a lot of its neighboring countries, the Gulf Arab states.

Another positive difference is that, in 2015, a lot of these Gulf Arab states, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, were not included in those [nuclear] negotiations and were very suspicious of them and ultimately were not supportive of that effort. Now, that may be different. They do have these better ties with Iran, and maybe that creates space for some kind of agreement at a regional level that could potentially be expanded. Long term, I do see this desire within at least certain centers of power in Iran that, in order to have a more balanced foreign policy overall and for Iran to benefit from trade even with Russia or China or India, they ultimately need the secondary U.S. sanctions gone. That camp obviously was most strong with people like former President Hassan Rouhani and Zarif, but there are also elements on the moderate conservative side that make these kinds of arguments still.

I think right now the best hope in the short term is continuation of these kinds of deescalatory models. From my understanding, the reason that deescalatory deal from last fall fell apart was partly because of Hamas’ October 7 attack on Israel, but also the money that was supposed to go to Iran and South Korea went to Qatar and Iran’s access to it is still heavily restricted there. The Iranians probably point to that as another reason why the United States can’t be trusted to follow through on its commitments. The best we can hope for in the short term is putting a ceiling on escalation, on confrontation. For example, having Iran not go beyond 60 percent enrichment of U-235 in its nuclear stockpile and ending attacks in the region. The United States can commit not to escalate more on our end and just keep that status quo until the next administration when I think, if there is any potential, we have to think bigger in terms of a bigger deal that takes into account other issues.

ACT: Are you suggesting a deal including the nuclear issue? How does that factor into the regional context? Israel, which has an unacknowledged nuclear weapons capability, is unlikely to contain its program. Saudi Arabia is negotiating with the United States to have its own nuclear energy program. Doesn’t that complicate the situation?

Toossi: I think a lot of this is contingent on the trajectory of Iranian politics, the elections, supreme leader succession, whether the current status quo is going to continue, which seems likely. So again, I am pessimistic. But I think when it comes to U.S.-Iranian relations, obviously the disputes are not just on the nuclear issue but also in the region from the Red Sea to Lebanon to Persian Gulf security, energy security. The United States still has this interest in getting out of this region to dedicate more resources to China and elsewhere. There are some in Iran who still think they need to get rid of these secondary U.S. sanctions. In the United States, there are many people who would say that we need to get off a war footing with Iran and dedicate more resources elsewhere in the world. For the Iranians, I think one lesson of the JCPOA was that, after the Americans, ultimately all these other issues, such as regional conflicts, prevented the JCPOA from being successful in the region. All these other differences now make me very pessimistic about the prospects for a grand bargain, especially after everything that’s happened in the past 10 years. I think the most we can hope for in the medium term is just putting a lid on further escalation.

ACT: If there were to be any agreement on the nuclear issue, would Russia and China be part of it? What are they advising Iran to do? How are they influencing Iran’s engagement with Israel?

Grajewski: On the question of whether or not any kind of deal is plausible, one of the things that makes it much more difficult is that a lot of the knowledge gained that Iran has had with working with higher enrichment levels, with more advanced centrifuges, that can’t really be reversed. On top of that, there is the issue that part of the JCPOA’s provisions expire by October 2025. So, no longer will the snapback sanctions be enabled, and there are sunset provisions that expire then. That being said, I do think there is a will within the United States and within Iran to get to a level or at least some kind of deescalation where there is a partial restoration of the JCPOA. Whether or not Russia and China have a role in restoring the JCPOA, I’m actually not quite certain about that right now. With the relationship we see between Iran and Russia, there has been a real difficulty with any kind of discussions on the JCPOA. First, Iran’s provision of drones [to Russia] likely violated part of the embargo that expired in October 2023. On top of that is the question of ballistic missiles. I think it’s really important to say that we haven’t seen Iranian ballistic missiles appearing in the war in Ukraine, and that’s very positive if we’re thinking about the prospects of any kind of discussions of the JCPOA. Perhaps it does reflect a conscious choice on the side of the Iranians not to deliver ballistic missiles. There have been reports on ballistic missiles, but I’ve seen no evidence of them actually arriving or Iran actually making that decision.

ACT: If Iran were to provide ballistic missiles, what would be the fallout?

Grajewski: The E3 [France, Germany, and the United Kingdom] really made clear that was a redline for them. One thing that is an issue is that ballistic missile deliveries to Russia would be far more escalatory than the drone provisions. But when it comes to the negotiations with the West and Russia and China’s role, I don’t see them playing a large role or at least not a positive role. China has been acquiescing to Iran’s expansion of its program. We’ve heard that, in [U.S.] Assistant Secretary of State Mallory Stewart’s discussions with the Chinese, there’s been some indication that China would be willing to pressure Iran not to continue with an expansion of its nuclear program. But the Chinese don’t want to assume this role as a mediator between the West and Iran.

With the Russians, there’s more of an emboldening of Iranian positions. Russian acquiescence to Iran’s kind of progression expansion has been a shift from its position prior to the war on Ukraine. This complicates the dynamics, especially when we’re thinking about it in the P5+1 context. One issue relating to Russia is Iranian support for the war in Ukraine on the side of the Russians. Right now, in the negotiations, especially within the IAEA, Russia emboldened Iran while China has taken a step back. Before the war in Ukraine, Russia was a really important and useful mediator. It pressured Iran to comply with the IAEA, either with the reinstallation of cameras or coming to the negotiation table after Raisi was elected. But that’s not the case anymore, and that complicates things. On U.S.-Iranian back channel discussions, I think Russia’s influence is looming but it’s not as present as it is within the P5+1 and IAEA contexts.

ACT: Any other comments about the Russian and Chinese regional roles? To add another question: Iran’s acting foreign minister, Ali Begari Khani, has conducted talks through Oman with the United States. What have they achieved? Could that be a possible channel or is it a continuing channel for deescalating not just political tensions but nuclear tensions going forward?

Vaez: On the first question, I think there is an element that one has to take into consideration, which is that Russia and China have a much higher threshold of tolerance in terms of Iran’s nuclear capabilities than is the case with Western countries. Now with growing, worsening great-power competition, both countries have an interest in making sure that the United States is preoccupied with concerns in the Middle East, as long as that doesn’t infringe on their own interests with Iran, especially on the Chinese side in terms of their ability to access energy resources in that part of the world. But if the United States is bogged down in the Middle East, that means that it cannot focus on China, and it’s a distraction from the war in Ukraine. Both of those things are positives for China and Russia.

In terms of negotiations that have occurred in Muscat, to the extent that we know, these are not aimed at crisis resolution but at crisis management. Iran and the United States have tried to keep a lid on the current tensions, whether it’s disagreements in the region or the nuclear standoff, rather than trying to think about what kind of future diplomatic solution could be found to address these in a more sustainable fashion. From what we know, a good part of these meetings is focused on exchanging threats and warnings of what would happen if the other side crosses certain redlines rather than engaging in a real quid pro quo bargaining aimed at resolving these issues. There is no guarantee that Bagheri Khani will become the foreign minister in the next Iranian government. If he is, by this point he has plenty of experience engaging with U.S. officials indirectly, and that could facilitate future negotiations rather than having someone who does not have such background. But we don’t know for sure that that would be the case. One element that has been introduced now, again as a result of the presidential transition in Iran, is that if there was the possibility of using the next few months before the U.S. elections in trying to lay the foundation for what comes next, that window has now been shortened because Iran would be internally focused in the next few weeks. I don’t think that the interim foreign minister or the regime as a whole would have an interest in serious engagement with the United States in this period.

Toossi: Ali knows the state of U.S.-Iranian negotiations and summarized them very well. On the China-Russia point, it was interesting that [Russian President Vladimir] Putin this week, when he was asked about Raisi, said Raisi was a very reliable partner for Russia. I think this gets to an important thing for China and Russia, and I’ve heard this from Iranians, that the kind of thinking in Tehran is that, during the Rouhani era, he was very much prioritizing the JCPOA, improving ties with the West…. We saw in the post-JCPOA era in Iran that, during that year, year and a half that we had the deal, those who sought better ties with the West were giving Western companies, European companies—Total, Airbus, Boeing—priority over Chinese and Russian ones. There are practical reasons for that, but for the Russians and Chinese, they didn’t have that assurance that Iran would be totally with them or closer to their orbits, even after Khamenei gave this kind of seminal speech during the Rouhani era, saying, “We should prioritize the East over the West.”

With Raisi, I think they really tried to make that clear. Even with the 25-year cooperation agreement with China, from what I’ve heard the Chinese wanted that earlier with Iran, as early as 2016 when the Chinese premier went to Iran. But then, it was slow-rolled from the Iranian side toward the end of Rouhani’s administration. I think that is a factor of Raisi’s presidency, and what Khamenei has tried to do is to signal to the Russians and Chinese that we’re not really counting on the West, we’re not fundamentally trying to improve our relations with them. I think tactically this space for secondary sanctions is potentially an avenue. In terms of primary U.S. sanctions, maybe the Iranians are never going to be interested in that; and they want to be closer to the Chinese and Russian orbits; and their bet overall seems to be that, in this changing global order and the emerging multipolarity, they want to go in that direction strategically. I think that stood out to me regarding these foreign relations of Iran.

ACT: After Rouhani took office, the desire of Iran’s young population for engagement with the West seemed effusive. If Iranian leaders now say our bet is with Russia and China, can they really drag their country into the embrace of Russia and China if the population is still interested in engagement with the West?

Toossi: I would argue that, in Iran generally…they’re more interested in the West, Western culture, especially the more cosmopolitan youth. That is the kind of media that they consume, the things that they’re interested in. So, that is indeed the fissure. Strategically, the leadership wants to take the country in one direction, but the thrust of society wants to go in another direction. I think this plays into the broader potential unsustainability of the Islamic Republic and its government model. With that said, there are deepening ties between Iran and China and Iran and Russia. Especially with Russia, for example, it’s not that economically significant; but I do see, interestingly, that there are more Iranians who travel into China, that China is also working to promote its soft power within Iran. But I would say that as things currently exist and given modern Iranian history, most Iranians want normal relations with the world, want to be able to travel to Europe and the United States especially, and the Iranian diaspora is in these places as well. Those are big factors that will continue to play into this appetite, that a big part of Iranian society, as well as the Islamic Republic’s political system, do have this interest in ties with the West.

ACT: How sustainable are the current embraces between Russia and Iran, China and Iran?

Grajewski: The political embrace of Russia in particular isn’t necessarily very popular with the Iranian population, and that’s been a long-standing grievance that has been expressed on the streets and during the Green Movement and even after the invasion of Ukraine, where you heard “death to Putin” chanted in front of the Russian embassy in Tehran. That’s partly because of historical grievances toward Russia, this legacy of imperialism. China also has been subjected to a lot of popular discontent, partly because of its business practices and the view that Iran is essentially being bought out by China. But yes, there is a huge gulf between the Iranian population’s view of its foreign relations and also its domestic politics, especially among the youth and the reformists opposed to its current trajectory.

I don’t really tend to ascribe to a binary between East and West in Iranian policy because I think it’s a little more nuanced and balanced. But there is that tendency, and I think you see it a lot right now, to emphasize the East. Whenever Iran discusses the East, it also includes South America. Raisi represented in many ways the conservative disregard for a lot of popular sentiment, popular expression, and freedom of expression, and I think that this is likely going to continue. I do think that the current trajectory… and also the acrimony with the United States, the acrimony with Israel, will continue. As optimistic as we’d like to be, there’s a lot more shadow figures within the Iranian bureaucracy, such as the IRGC, which is largely disinclined to support any kind of nuclear agreement, partly because sanctions help sections of the Iranian bureaucracy or what Trump would call a deep state. But yeah, I think that you’re right though. I do think that the population doesn’t necessarily ascribe to these views. It’s a shame, and I think hopefully things change.